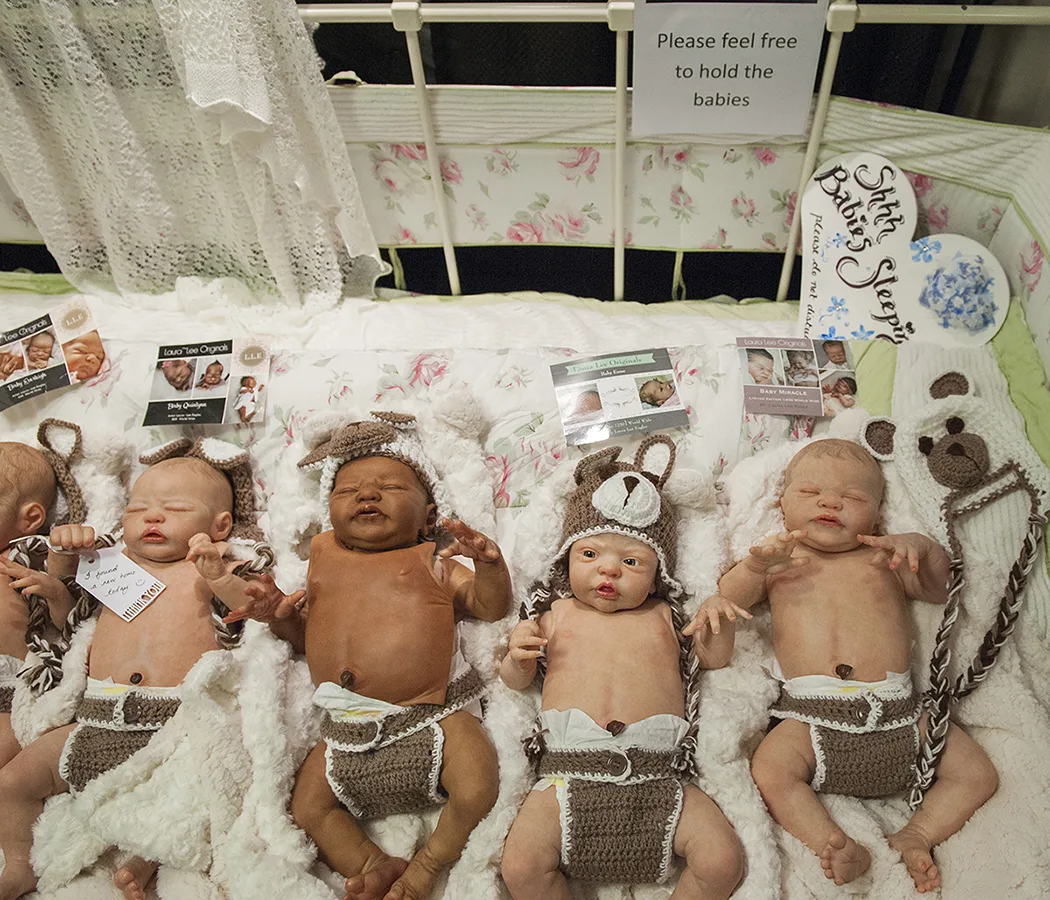

The babies in these photos weigh what a baby might weigh, they look lifelike, they have a birth certificate, often have a name and even smell real, but they aren’t real. They’re made from vinyl, frappe fabric and alpaca hair, and women around the world are buying them. They may have been told they can’t have children, or might have lost a baby in childbirth. They may yearn for companionship or a routine, or simply feel like they need something to nurture and look after. Karolina Jonderko has been getting to know some of these women for her project Reborn, photographing them as they take care of their little ones for as long as they need to.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers' own words. See the whole series here.

“All of the long-term projects I’m working on are based on loss, and on how people deal with trauma. Ever since I lost my mom in 2008, and had to deal with the resulting depression, I think the topic of loss has been at the forefront of my mind. With each project, I'm dealing with a different form of trauma, or with a different coping mechanism for it.

Back in 2012, I was visiting my sister in the UK and I saw a BBC documentary, My Fake Baby. It was about women who look after dolls as if they are real babies. When I saw them, it struck me that it must be such a powerful therapy tool. I never saw the funny side of it that some people see. I don’t know how you could laugh at these women. I was just curious about what the babies were giving to them, how they were helping them.

The first time I held one of them, it did something to my brain.

It took me three years to find some of the women who take care of these dolls. I went to a big fair in the UK where you can come with the whole family and choose from this huge selection of dolls. The first time I held one of them, it did something to my brain. That feeling is something I couldn’t show in the photos, but it’s incredible. It weighs a lot, and you need to support the head because it's like a sleeping baby. It even smells real, too.

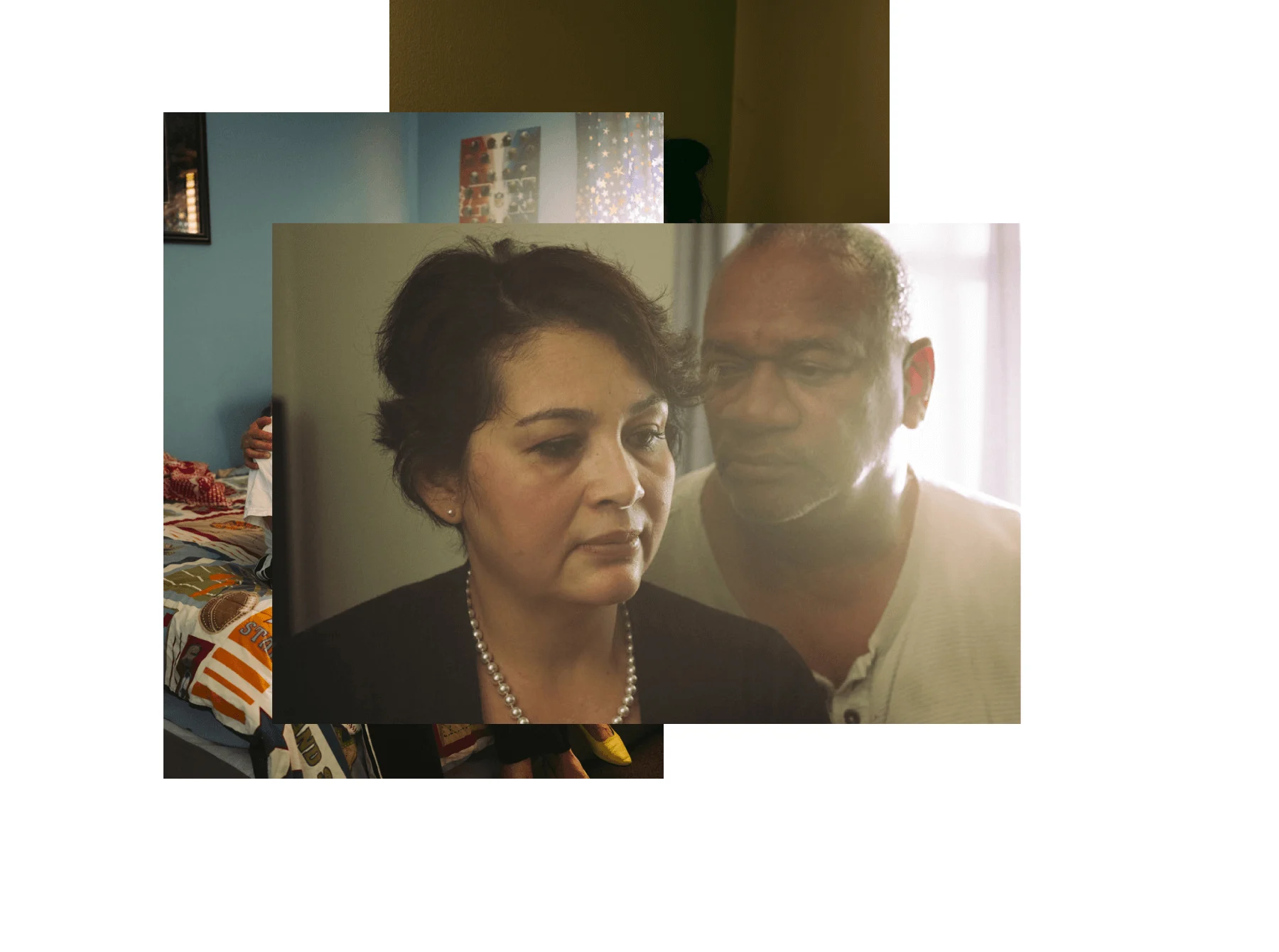

That was the beginning. I started in the UK, but then I found more women in Poland. It’s a sensitive subject to just approach people about, but I told them I was in therapy, that I was familiar with loss and trauma. I said to them, ‘I just want to support you in this. I want to find out how and why you do this,’ and they said yes.

It wasn’t easy at the beginning. I didn’t use my camera at all for the first six months, because I wanted them to feel comfortable with me. I told them that I can’t protect them, that no matter what I say in the captions, I can’t save them from being mocked. I can only show the topic as sensitively as I can. The UK newspapers always take very fragile women who have 200 dolls or are neglecting their own children. You can always find people like that, but they aren’t representative of the whole. I didn’t want to take advantage of them like the mass media does, so I was cautious at first. When one of them said to me, ‘Karolina, come on, start taking the pictures,’ I knew they trusted me, and I began.

I didn’t want to take advantage of them like the mass media does

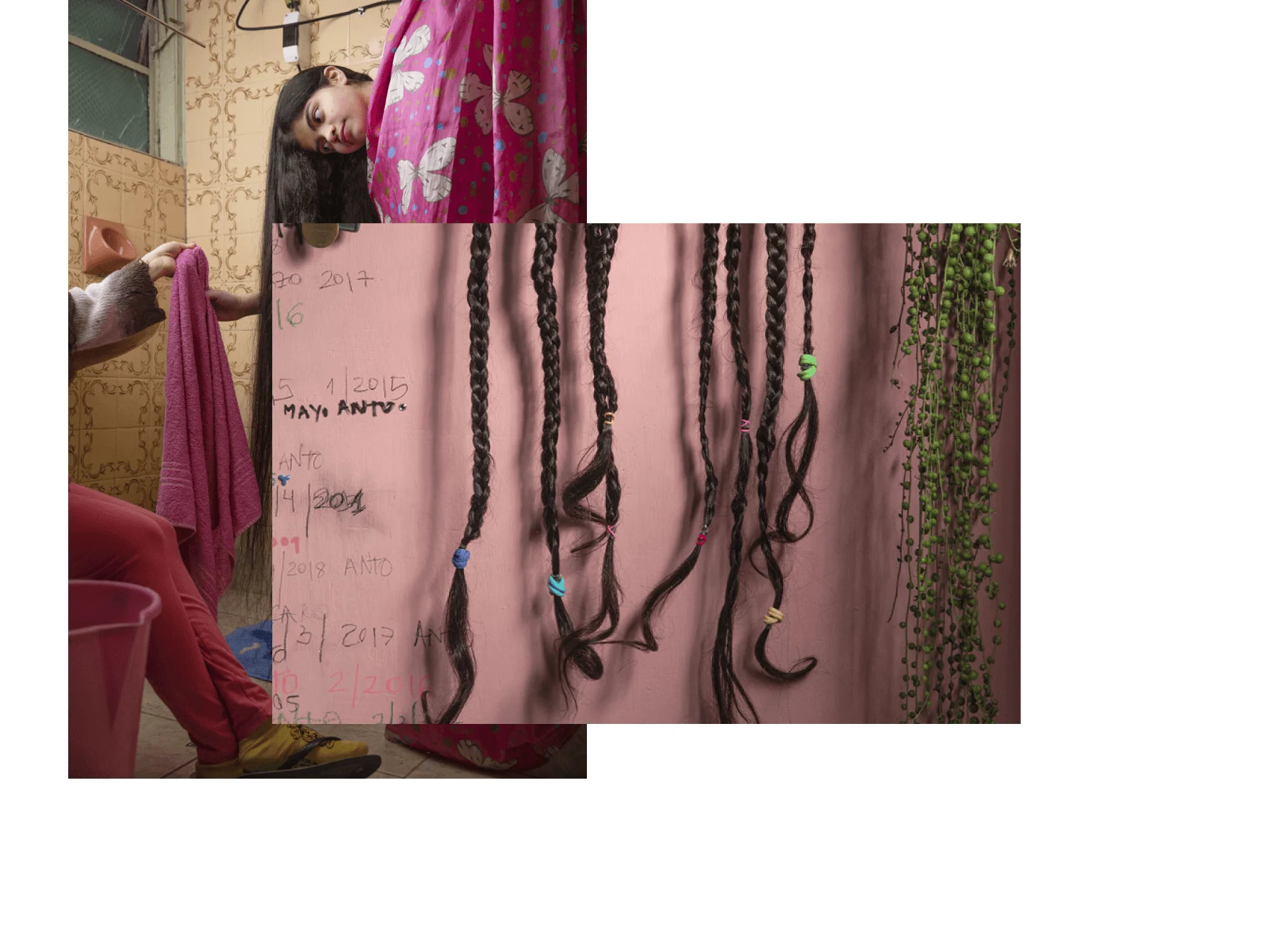

I didn’t want to do staged portraits of them. I used to do photography at weddings, and I’d be fine taking the more candid photos, but once the couple wanted to go outside and get official photos of themselves, I was so bad. So every time I went to see the women, I’d just ask them to do their normal stuff, to take care of the doll in the same way they normally would. I just wanted to spend time with them and capture their daily life as a mother.

Every doll is handmade; it’s an intricate process. Artists often make the dolls based on pictures the client has given them. Their hands and legs are made with vinyl, but the body is made from frappe fabric, so that it’s soft like the body of a baby. Once they’re made, artists paint them so that they look real, and then each strand of hair is put in one by one. When a woman buys a doll, she’s given a birth certificate that says the doll’s weight and height.

Some of the women love to take them out in public, and they like it when strangers interact with them. They like the attention. They like to talk about it with people and they are more open about it. But one of the women I met only took the doll out in her garden, because she was afraid of what people might say.

Magda had a doll for seven years. Her husband told me that he was just happy she was functioning again, getting out of bed in the morning to change the doll. He said, ‘I don't mind as long as she’s back to being herself.’ She finally got pregnant after seven years of trying, and then she put the doll away. She didn’t need it anymore.

It’s often the case that the doll was just needed for a period of time to deal with something painful. Another woman lost her baby in childbirth, and said that she came back from the hospital with empty hands and they hurt. She needed something to hold on to. I took her photo in 2019, and she wrote to me two months ago to say that she’s selling her dolls because she’s looking to adopt and she’s ready to move on.”