Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around. Each year, we meet a winner from each region and hear, in their own words, what went into capturing every monumental shot, from beautiful scenery to watershed historical moments.

This year, we’ve selected stories that show the impact of the climate crisis spreading far and wide, shed light on the experiences of migrants, and follow parents who were separated from their children due to strict prison systems.

Six photographers, six incredible stories from around the globe. We’ll leave you to dive in.

M’hammed Kilito, Morocco

“Before It’s Gone” for VII Mentor Program/Visura

Region: Africa

2022 was the worst drought year Morocco has experienced in nearly 40 years, and M’hammed Kilito has spent years turning his lens to the country’s climate crisis, capturing those affected and painting a picture of the natural oases, which are at severe risk of wildfire, and that are so vital to sustaining life in the desert.

“According to the World Bank's climate and development report, Morocco is now on the cusp of an absolute water shortage, with water resources dwindling to a mere 500m3 per person per year–a threshold that could have catastrophic consequences for the population and the economy.

I participated in the Caravane Tighmert Residency in 2016, which is an art residency held in Tighmert oasis. There, I had the opportunity to meet with the local population and gain a deeper understanding of the importance of oases; the way the biodiversity, animal habitats, and fodder crops they offer are vital to life in the desert. I discovered that recurrent droughts and fires, changes in agricultural practices, and overexploitation of natural resources mean oases are facing a range of challenges that are endangering their very existence.

Through my research and field trips, I also became increasingly aware of the cultural, historical, and ecological significance of oases. These unique ecosystems have served as bridges between Morocco and the rest of Africa for centuries, fostering trade, religious and political ties, and shaping the forms of social, political, and economic tribal organization. I wanted to highlight the rich tangible and intangible heritage of oases affected by the closure of the border between Algeria and Morocco, along with the effects of globalization and rural exodus.

Sadly, water stress is leading to a decline in agriculture, livestock, livelihoods, and food in the oases. It’s also accelerating the displacement of the oases population. For many Moroccans, the dryness and drought mean not only the loss of biodiversity, but also the loss of their cultural heritage.

When we think of Morocco from abroad, we often envision the desert, oases, and camels. Yet, for the majority of Moroccans, the desert remains unexplored, and the oases are ecosystems that are little known. Through my project, I aim to shed light on the lives of the men and women living in the oases by sharing their stories, showcasing the beauty of the oases, and raising awareness about the dramatic effects of climate change on these unique ecosystems. My objective is to amplify the voices of local inhabitants, environmental activists, ecological organizations, scientists, and researchers who are working to preserve the oases.

These issues are rarely covered by the media and are largely unknown to the public. My research also aims to better understand different approaches, practices, and programs applied to the valorization, conservation, and sustainable development of oases, which are known to be environmentally sensitive. Ultimately, my goal is to use my photography to spark a conversation about the future of oases and inspire action to protect and conserve these invaluable ecosystems for generations to come.”

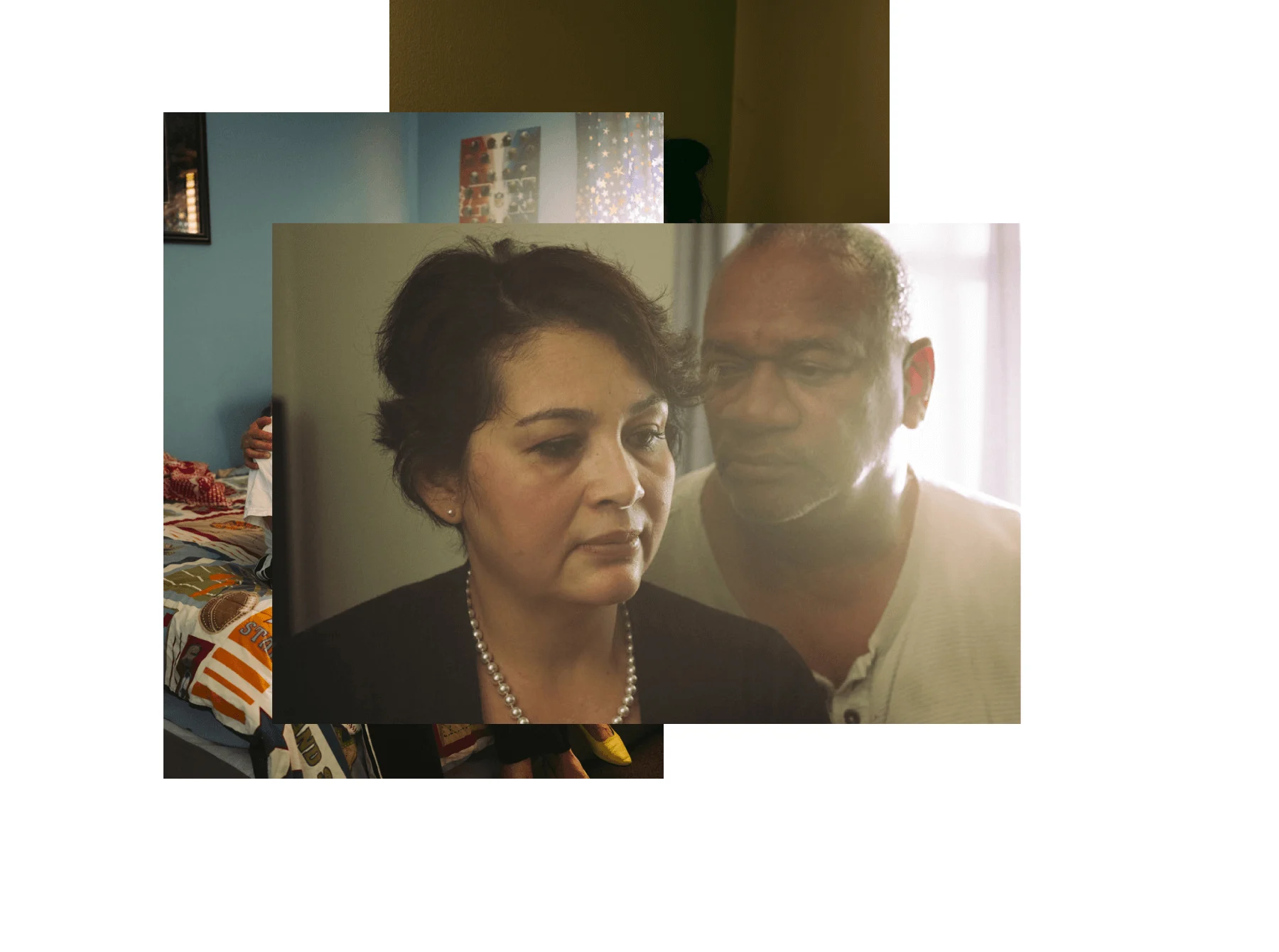

César Dezfuli, Spain/Iran

“Passengers” for De Volkskrant

Region: Europe

In 2016, working aboard a German rescue ship, César Dezfuli took portraits of 118 people rescued from their adrift boat on the Central Mediterranean migration route. Noticing that stories around refugees so often reduce humans to numbers and statistics, Cesar set out to track down some of the people he photographed that day to learn more about their stories, and find out where they are now.

“In 2016, I had the opportunity to board the German NGO Juggend Rettet’s rescue ship ‘Iuventa.’ My aim was to show what was happening on the Central Mediterranean migration route, to represent those involved in a dignified way. In the three weeks I was onboard, nearly two thousand people were rescued, and I focused on the passengers of a single boat. Every day the NGO had to report to the Italian authorities the number of people rescued. These people became numbers without identity, under the umbrella of the term “migrant,” which virtually negates their uniqueness and personal stories and simplifies the migration narrative.

Moving away from the mass of photographs and focusing on the identity of the 118 passengers on that boat allowed me to begin to change the narrative, to speak of individual stories. I did think at the time about the possibility of locating someone later and following up, but as a one-off, not to the level I’ve reached. Throughout these seven years of work, I’ve managed to locate 105 of the 118 passengers on the ship and I have already met 75 of them, who are living in different countries all over Europe.

The second part of the project has several layers both photographically and narratively. On the one hand, I take a second portrait of them, trying to maintain a similar distance and composition to the photo taken on the day of the rescue, focusing again on their identity. The idea is to show how these people have evolved, not with the aim of pointing out that their life is better in Europe, because this is not always the case, but to explain that the deplorable circumstances they were in when they were rescued at sea is the consequence of the lack of safe methods of travel for these people who are forced to migrate in the way they do.

So often, these people are represented by numbers, so it’s essential to capture the personal, human stories. Today’s world—the way contemporary societies are shaped—is the result of historical migratory processes. And current migrations are a continuation of these processes that will shape the societies of the future. It is natural and inevitable. However, migration is currently treated in politics and the media as an abstract and dehumanized issue, and increasingly as a threat. We need to begin to reflect more deeply and empathetically on migratory movements and those of us who document them need to do so with greater responsibility. We’re contributing to the construction of the collective imagination around migration, and we have to decide whether to entrench stereotypes and continue to talk about migration in terms of numbers and statistics, or to represent people who migrate from an individual perspective that facilitates an understanding of their reality.”

Anush Babajanyan, Armenia

“Battered Waters” for VII Photo/National Geographic Society

Region: Asia

Due to climate change and the diversion of water sources for material reasons, the Aral Sea—once the fourth largest inland sea on the planet—is now a shadow of its former self. Anush Babajanyan has been documenting this under-reported environmental crisis, and highlighting the once-thriving agricultural communities of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan whose lives have been so drastically affected.

“Water-related issues exist in many parts of the world, but having worked in Central Asia since 2015, I’ve paid particular attention to the environmental crises there. It’s a region that’s quite overlooked by the media, and I believed the water situation in the four countries I focused on needed to be shared with a larger audience. The reality of the retreating Aral Sea is quite known, but there’s so many individual stories of those affected that need to be heard.

‘Battered Waters’ shows a few aspects of water management. I believe the issues come about mostly as a result of human activity, often because of short term goals. For example, as a dam was built on a river, the only road to one of the villages nearby was covered by water as a result. In the aftermath, I photographed a man who used his boat to transfer people from one shore to another.

I tried to find and feel the reality facing these people and capture their emotions; that was my purpose. I cannot say I looked for a different perspective on the subject, but rather one that spoke truly to what I was seeing and to the feeling that I was getting in the field.

I encountered resilience with so many people in Central Asia. I spent a day with a group of women working on a rice field, a heavy job and one that’s not paid well. But the ladies played music on their portable speakers and danced and sang during their short breaks. That was something I truly wanted to document.

It was also special to photograph a day in the life of a widower named Nurislam Gainutdinov, 72, by the Toktogul reservoir in Kyrgyzstan. The fluctuating water levels had affected his home, but he kept living by the shore, adapting and adjusting his lifestyle, all while still grieving the loss of his wife.”

Carlos Barria, Argentina

“Maria’s Journey” for Reuters

Region: North & Central America

In 2017, Maria and her two young daughters were separated after attempting to seek asylum in the United States. Maria was sent back to Honduras as her children remained in the US with their older brother, and Carlos Barria documented her journey as she fought to eventually be reunited with them.

“I was working at the White House as a member of the press pool when the new immigration policy of ‘zero tolerance’ was implemented. I witnessed first-hand the political turmoil this policy unleashed in the capital, but I wanted to go a step further and report on the way this shift was separating families at the border. I got in contact with our team of journalists focusing on immigration and learned they were looking for an example of someone affected by the new measures. I told them I was interested in working on this story and eventually they introduced me to Maria.

I’ve covered immigration at the Mexican border off and on for several years. Also, as the son of immigrants and as an immigrant myself, this story has special meaning for me. It speaks to the basic aspiration for a better life and a willingness to make sacrifices for a brighter future. Maria’s story shows what people are capable of doing for their children. In her case, she was given an impossible choice and agreed to be deported back to Honduras in a desperate attempt to secure a safe place for her daughters in the United States.

In 2017, Maria and her two young daughters crossed into the United States to seek asylum. Once apprehended, she was given a terrible choice: Leave the country, either with the girls or without them. Rattled by the threat of Honduran gangs in her hometown, Maria decided the girls would be safer in the United States. Under the Biden administration Maria was eventually reunited with her daughters.

Something that stood out for me about Maria’s story was her incredible courage and love for her daughters. She kept a positive attitude despite all the odds against her, and she often still manages to express gratitude. I also admire her perseverance in staying so connected to her daughters through their separation, asking them about homework during video calls, and telling them stories before they went to sleep. She was always smiling and cheerful in front of them, but I also witnessed her crying right after a call. Obviously, this made me feel sad, but Maria never lost hope. She was unbowed. And that made me feel optimistic. She’s a fighter.

It’s important for me to keep putting the spotlight on this issue. There are still hundreds of children who remain separated from their parents today. Maria’s story has a happy ending, but we as journalists have to keep telling stories like these to the public. Hopefully, bringing these stories to light informs public debate in a way that is grounded in reality, not just numbers.”

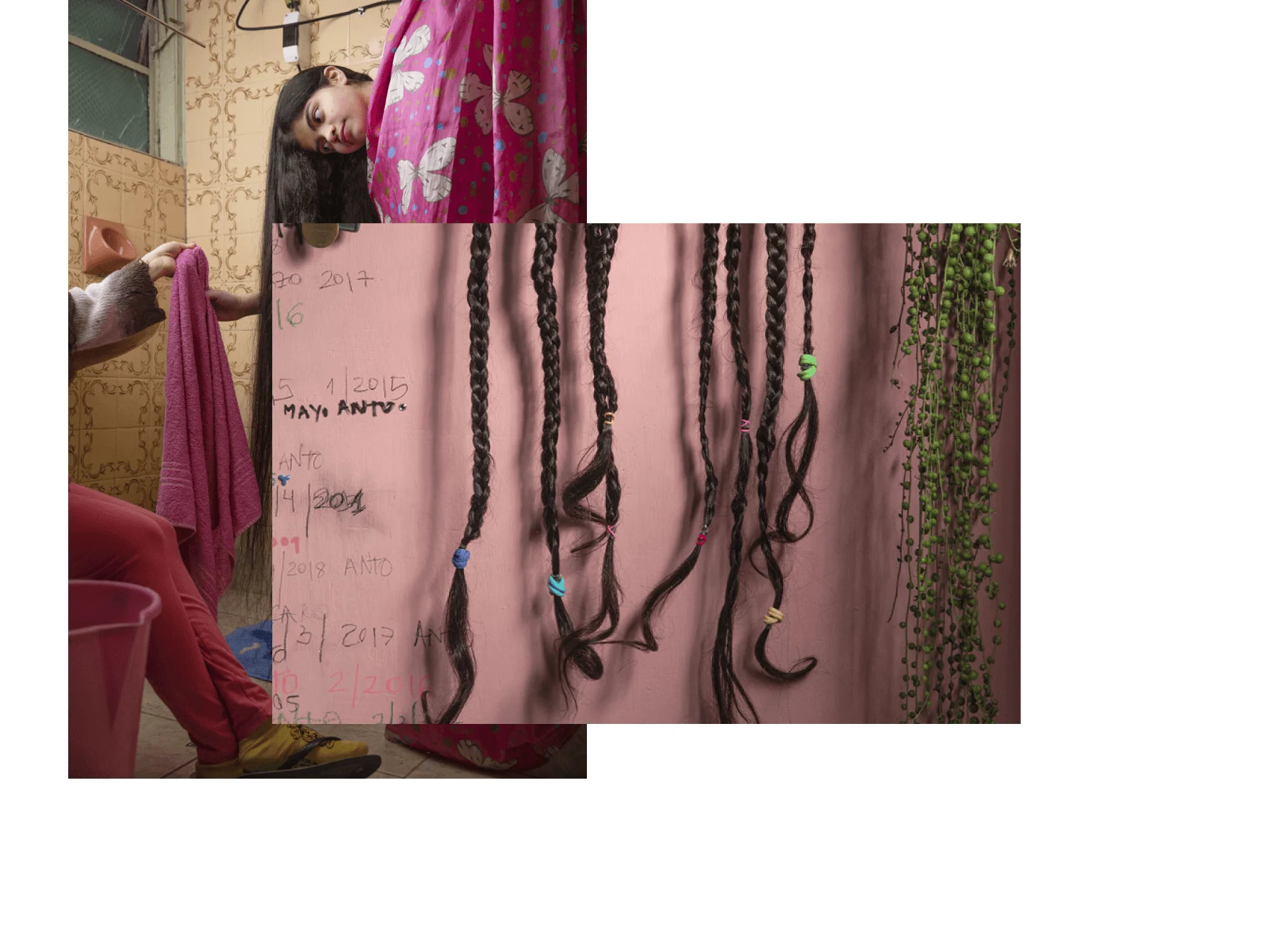

Johanna Alarcón, Ecuador

“Shifting” for Magnum Foundation

Region: South America

Johanna Alarcón, who has had a family member of her own incarcerated, spent years with Valentina, a young Ecuadorian, whose mother was sent to prison. Together, they created a multimedia project that explores family, love, separation, and the overwhelming impact their country’s prison system is having on mothers and their children.

“I’ve worked on art and hip-hop projects in prisons, and those experiences allowed me to create this story thanks to an intimate relationship with Valentina and her mom. I believed in and understood the dreams of Valentina and her mother, understanding what they’ve had to go through and feeling the distance they experience when they’re separated. It was a joint decision to narrate what lies beyond the bars, what dreams inhabit in sons and daughters who hope to be reunited with their mothers and who refuse to grow up in the shadow of prison stigmas and the violence of the penal system towards them.

The goal of this project was to paint a picture of an almost adolescent girl who is creating her own story, fighting not to be solely defined by her mom’s sentence, and by the image of prison society has. This work explores an intimate experience of life in jail, telling the story of the many families facing distance and confinement as they await their chance to start again. ‘Shifting’ is a multimedia short film we made together; it includes images of her daily life, her mother’s songs from prison and an animated piece based on their last memory together.

The ‘war on drugs’ is harming women and their children around Latin-America. Incarceration disrupts interpersonal relationships at all levels, including parent-child bonding due to extreme isolation policies. It severely punishes children who suffer additional stigma related to their parents’ crime. For inmates’ families, distance represents a big problem in terms of time and money. Ecuador is facing the worst prison crisis in history, where 54% of women prisoners are sentenced for drug-related crimes and almost 90% of them are mothers. Currently, 3 out of every 10 prisoners in Ecuador are related to micro-dealing or drug possession. The majority come from marginalized backgrounds; many are homeless, ethnic minorities, women and single moms arrested with insignificant amounts of drugs. This disrupts interpersonal relationships at all levels, including parent-child bonding. These changes have repercussions on the lives of children—secondary victims—who live in unfavorable socioeconomic situations and amidst extreme isolation policies that deny them physical time with their mothers.

Valentina and I worked together for several years; the most impressive thing has been watching her grow up. I met her when she was seven years old, and now she’s 13. We spent many beautiful moments developing film, at the waterfall, playing with butterflies in the forest, and flying kites. We also shared difficult moments, seeing her mother so far away. Being with her makes me see the life, love and innocence of a girl who has been through a lot and makes us reflect on how violent the system is to those who deserve it the least.”

Chad Ajamian, Australia

“Australian Floods in Infrared”

Region: Oceania

Chad Ajamian combs through hundreds of aerial, infrared photographs of his native Australia, most often to help the rescue efforts in the wake of disasters such as floods or wildfires. In 2021, after the floods in New South Wales, his eye was vital to helping first responders on the chaotic ground get a better understanding of the situation as they went in to help those affected.

“It's this ability to ‘see the unseen’ which characterizes the explorative discovery and unique contrasts that infrared photography can achieve. The source data is captured via an aircraft-mounted sensor to capture post-catastrophe impacts on the environment and the community. This data captured by the NSW Department of Spatial Services is provided to the public, and is used by a variety of government agencies including emergency response on the ground, and for recovery efforts, as well for scientific research after the event such as impact assessments.

As an independent artist, through the creative commons licencing of the data, the raw data was imported into GIS Software (Geographic Information Systems), where I scanned through the captured data for photographic compositions and scenes, extracting sections of interest and processing them into a Lightroom compatible format, and they were then treated as any photograph, with standard modifications such as straightening, cropping, and post-processing.

Situational awareness is critical for emergency response and recovery, both for teams on the ground and decision makers. Natural disasters are intrinsically chaotic, and any insight into the extent of their impacts is invaluable to their response. Communities are often isolated, access is limited if available at all, and response teams can be restricted by the same constraints as the community they’re assisting. Aerial infrared photography can be captured as soon as weather conditions allow, sometimes within 48 hours, and can instantly provide unparalleled insights into the extent of the emergency. Initially, this can be used to identify isolated populations and those requiring emergency assistance, as well as supporting response teams in identifying potential ingress routes, such as to repair critical services.

For me the question of 'traditional' vs 'practical' photography makes me think of the art vs science debate. 'Traditional' landscape photography, contour lines on a map, geology, botanical sketches, the radar on your weather app, selfies with your cat—it's all capturing and conveying an interpretation of an environment. All are creative forms, and all are documenting information about the physical world. There may be a philosophical divide between art and science, but both are celebrations and products of curiosity, exploration, and communication. Being both a scientist and a photographer, I felt there was a significant beauty in the interplay between the scientific and creative applications of the infrared technology.”