Since the Siamese revolution of 1932, Thailand has seen four massacres and 13 successful military coups. With her series, “The Will to Remember,” Thai photographer Charinthorn Rachurutchata hopes to bring the memory of the 6 October massacre in 1976—and the fight of Thailand’s youth—to the fore.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers’ own words. See the whole series here.

The opinions expressed in this first-person interview are those of the photographer and do not necessarily reflect those of WeTransfer.

“Like many other Thai people, I didn’t really know about the 6 October massacre. We don’t learn about it at school—textbooks don’t mention it, it’s not on the television, and growing up, no one talks about it. It’s a foggy memory, like a collective amnesia: the silence of the nation.

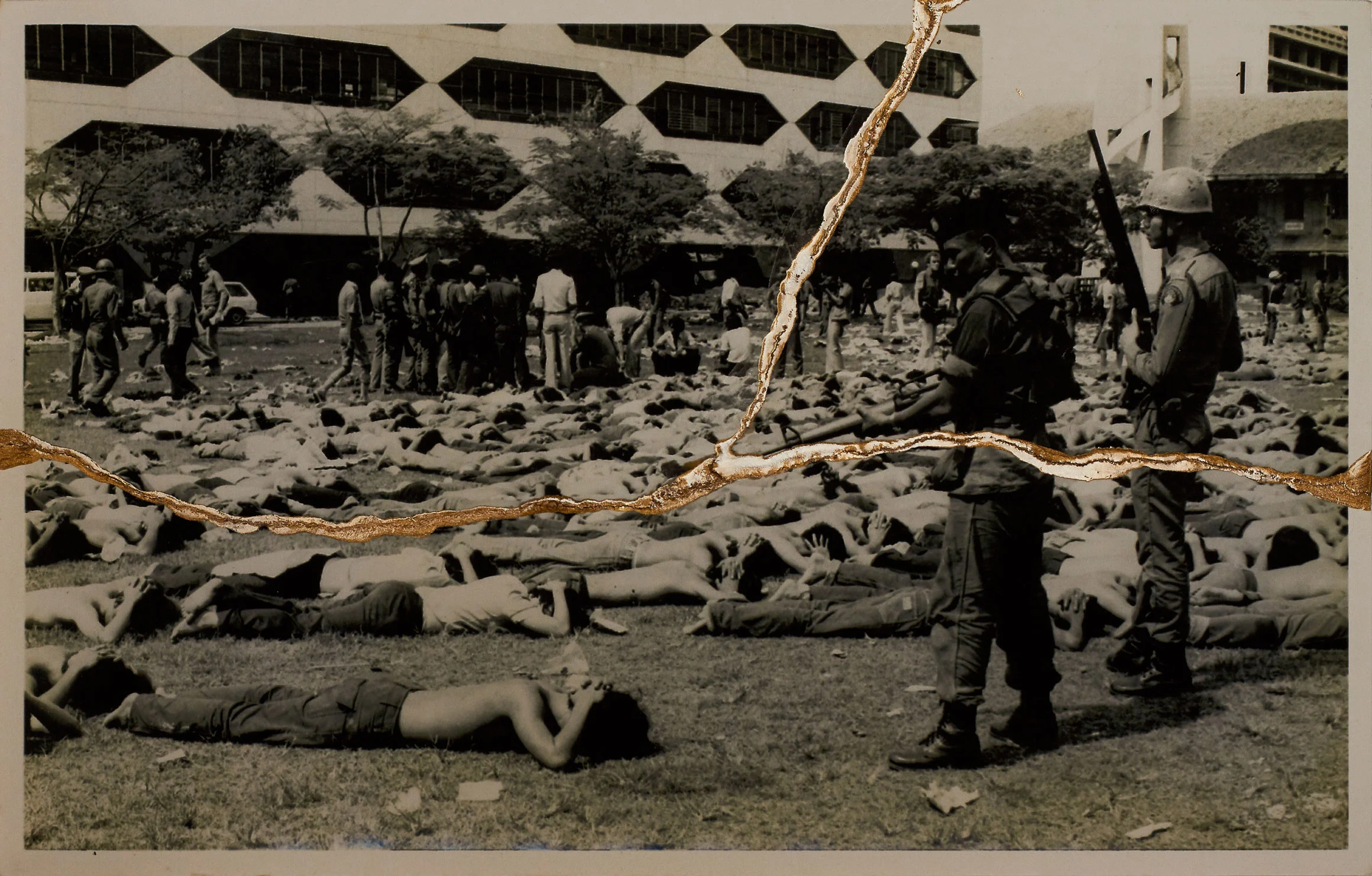

In 1976, on the morning of 6 October, the students at Thammasat University tried to protest against the return of the former dictator Thanom Kittikachorn, a vigorous anti-communist. The military, police, and civilians blocked exits and began shooting into the crowds. At least 46 people were killed and over 3,000 were arrested. To date, the military and the monarchy have never publicly acknowledged the massacre.

At that time, the Cold War was still going on, and Thailand had been promoted by America as the barrier against communism. Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam had all become communist countries, and their monarchies were destroyed. The anti-communist propaganda was overwhelming—even some right-wing Buddhist monks said that killing communists was not a sin.

That is something that still haunts and traumatizes Thailand to this day—it wasn’t just the military, it was citizens against citizens—they beat people and burnt them. They hung their corpses and hit them with chairs while people stood around and cheered. When I started to study, I learned about this and I tried to understand, but it made me so angry with my country. They’ve been lying to the people and it just feels like a betrayal.

It’s a foggy memory, like a collective amnesia: the silence of the nation.

My house is on the way to the Democracy Monument, so almost every protest that happens goes past us. Since I was a kid, I’ve witnessed many protests walking by, but I never really questioned why. There have been two massacres in Thailand in my lifetime. The first time I was ten and the second was in 2010, and in between them there were three coup d’états. It makes you think, ‘what's happening to my country? How did we get here?’ So I started to study the politics and history of Thailand. That was around 2019—my photography was becoming more political and then I went to do a residency in Japan, and that’s where I learnt about Kintsugi.

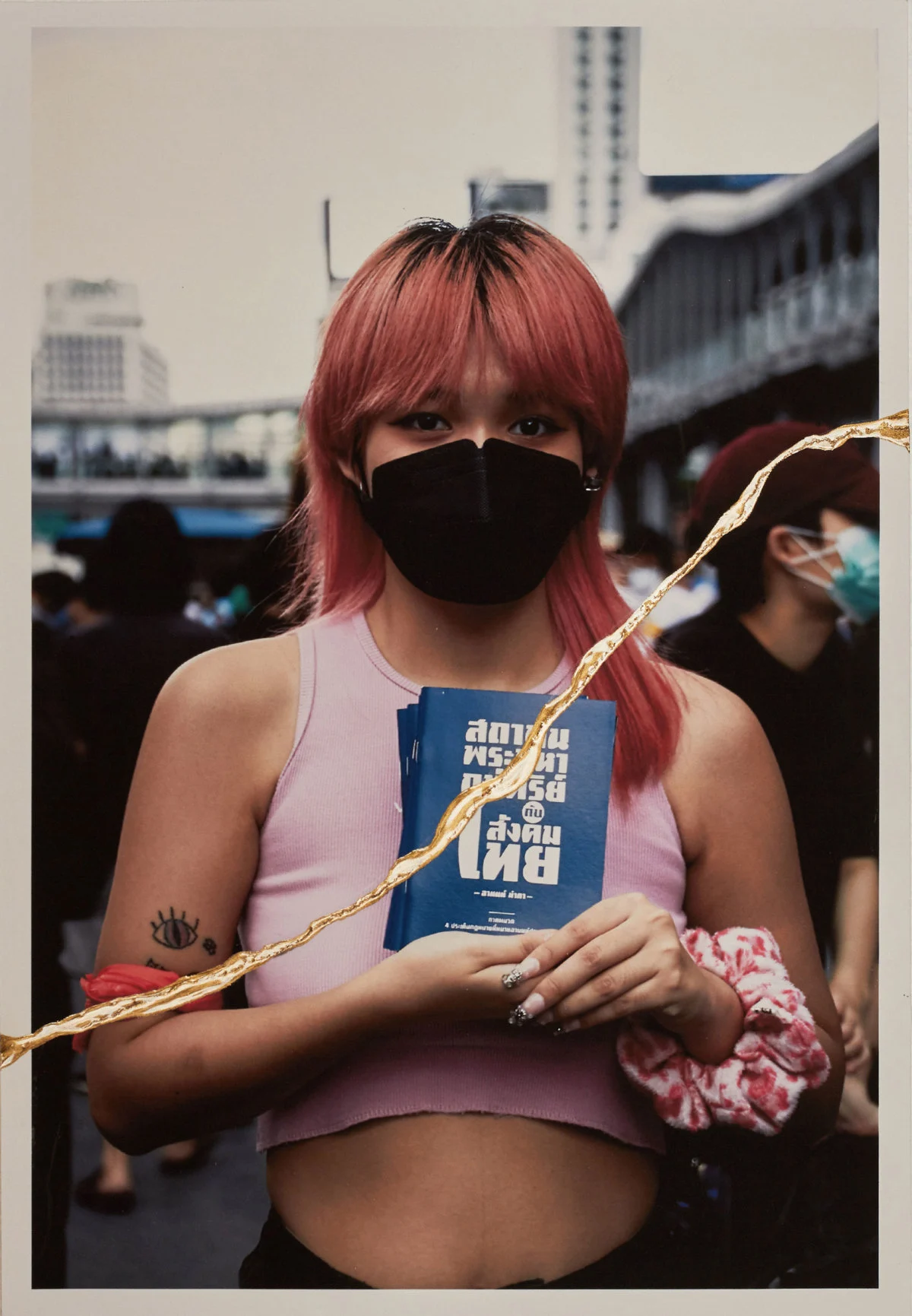

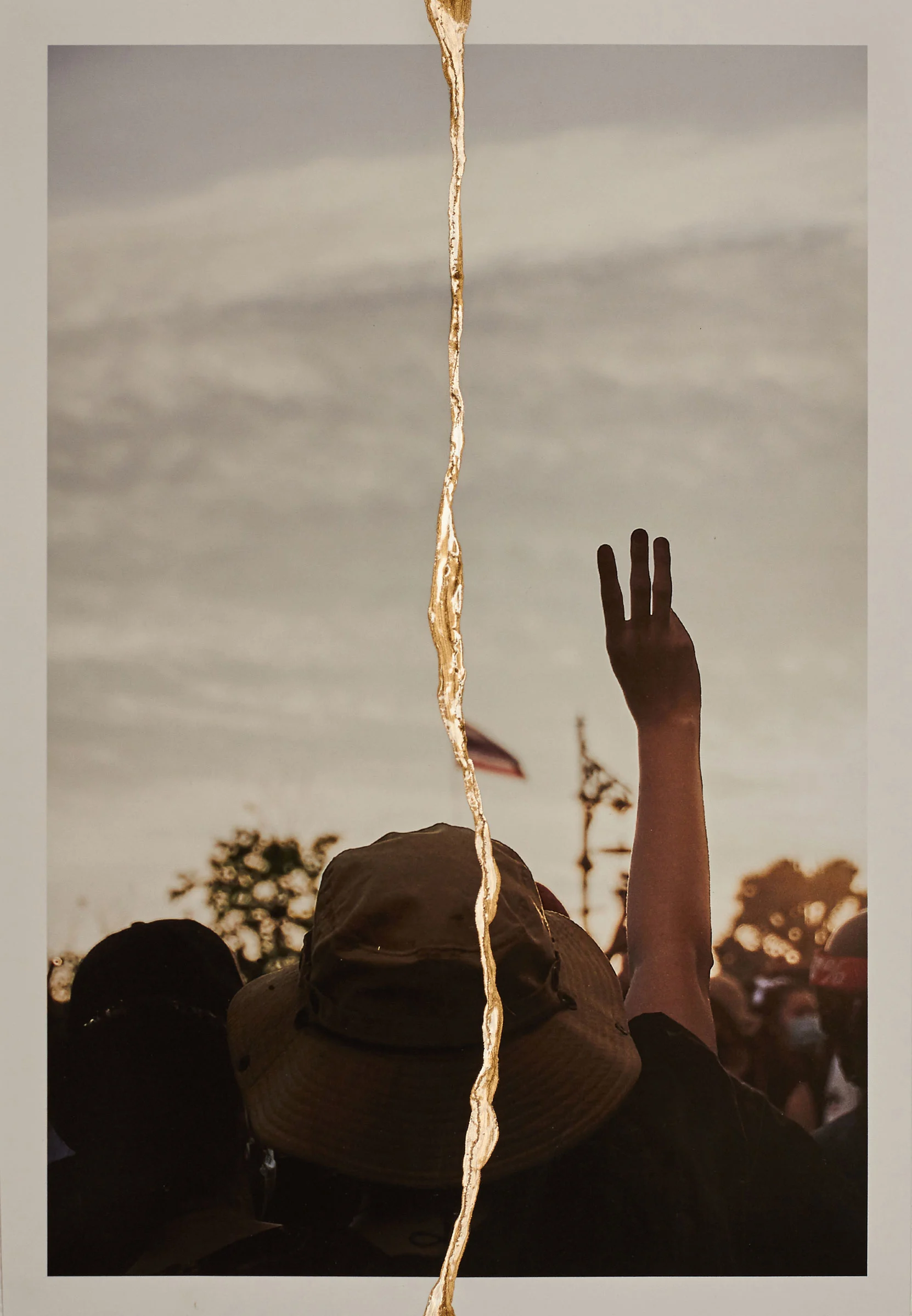

Kintsugi means ‘golden joinery,’ and typically refers to mending broken pottery using powdered gold. The philosophy and psychology of the art is about healing: It’s about seeing the imperfections, the wounds, and the trauma as a part of an object. Because of the technique, the pottery becomes stronger as you seal it—so the technique, psychology, and philosophy are all connected. At first, I started to do Kintsugi on the archive photographs. I tore them apart with my hands, but also with my head: I took the time to meditate on them and focus, I prayed for the victims, and I put my whole heart into it. When I mend them, leaving them with golden scars, I think of hope for the future and bring everything together.

Three months after I started doing Kintsugi, the protests started happening, too. In the beginning I didn’t see the connection with my work; I just joined the protests. As a photographer, I started to document them and I saw how the youth and the people think—how the massacre has shaped the younger generation. I think of the slogan “Let it end in our generation.”

Maybe 2020 is the year of the protest and 2021 is the year of arrests, so we’ll see how it will go in 2022. But the young generation, they’re awake now and I don’t think they’re going to go blind again. I think the fight is going to keep going in some kind of way, whether that’s me making art, or people protesting, I’m hopeful! The more I study, the more I see how Thailand got to this point—everything is connected, and we really need to learn about this history. It’s so important.”