For as long as she can remember, visual storyteller Rehab Eldalil felt a magnetic pull to Sinai and the Bedouin community, but never understood why. In a strange twist of fate, she discovered not only that she has Bedouin ancestry, but that those ancestors were most likely part of the Jebeleya tribe, who’ve been inhabiting Sinai for more than 1400 years. In her series, “The Longing Of The Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken,” Rehab engages with the profound gesture of unfolding history, uncovering the sense of belonging she always craved, while reimagining her practice as a site for collaboration and community.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers’ own words. See the whole series here.

The opinions expressed in this first-person interview are those of the photographer and do not necessarily reflect those of WeTransfer.

“I somehow always felt that I belonged in Sinai. I began this work in 2009 to seek answers about my unexplained spiritual connection with the Bedouin community. During my research, I was sitting with a Bedouin Elder who was curious about my last name. He explained that Eldalil means ‘the guide,’ and that there was an Eldalil family in the community who had left four generations ago and settled in Zagazig, the same place in which my father was born. At that moment, I realized I was rerooting myself without even knowing it.

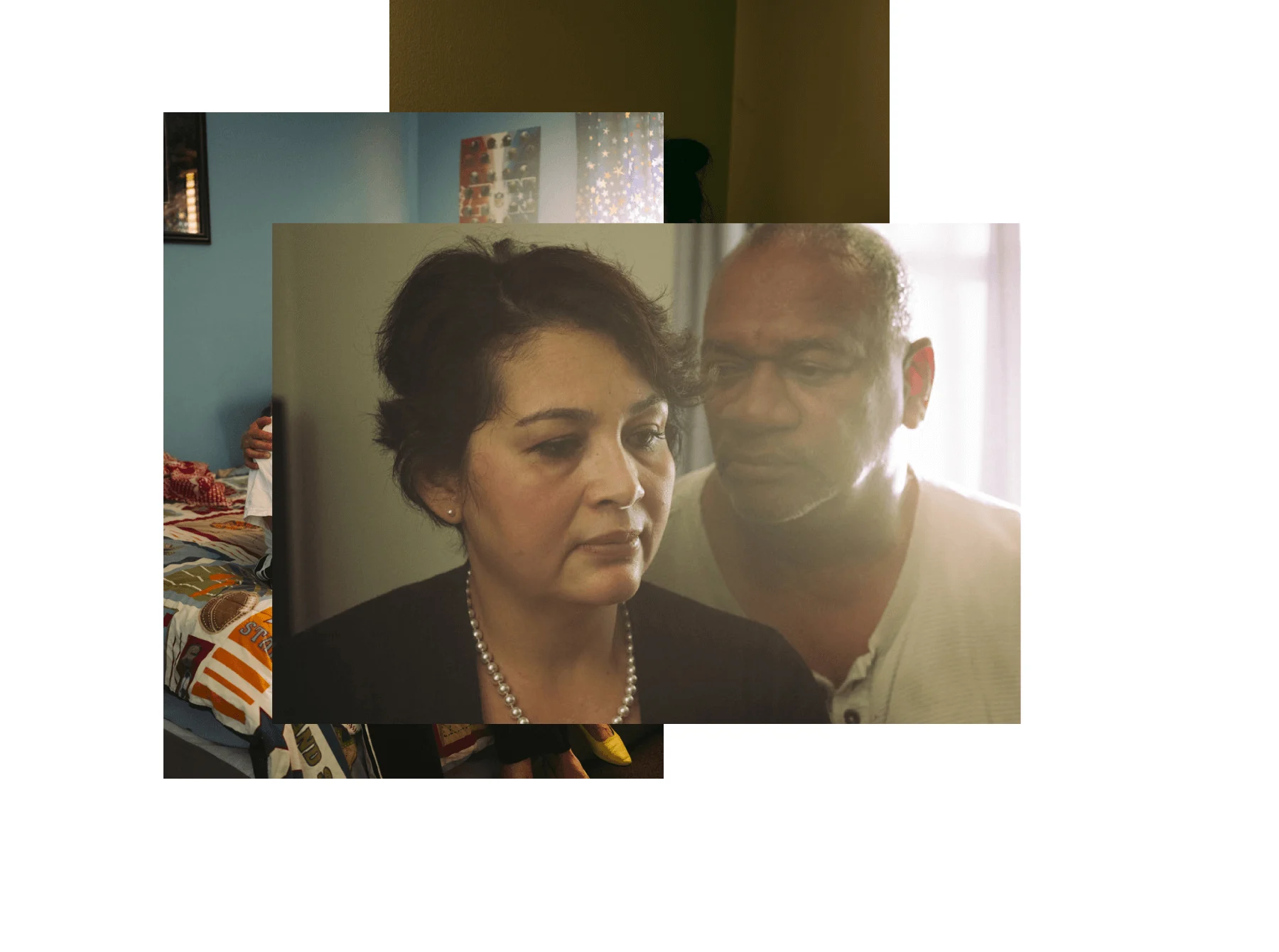

It sounds crazy, but I had no idea about my ancestry growing up. My father is a military man, and he’s quite closed off. When I first confronted him, he ignored my questions for two years. Over time, he slowly opened up about our ancestors, both the Bedouin and Palestinian sides. We’d go on holiday in Sinai throughout my childhood, spending time with the community. When I became a teenager, I’d run off to Sinai all the time and build my own relationships. That grew into advocacy, and I became a civil rights activist using my camera. I wanted to challenge Bedouin stereotypes from the West and within Egypt itself.

We all have a need to belong and this project enabled me to be comfortable in my skin.

During the Israeli occupation (1967-1982) Bedouins remained on their land to protect it, and they helped Egyptian forces regain possession of Sinai during the war. A long struggle began to secure civil rights and basic needs like education and medical care. As my photographs began to sell, all the money went back into the community, and I raised enough to build a community clinic in partnership with the elders. We opened in 2018, and it's something I'm very proud of.

The first time I realized my identity carried certain baggage, that being Arabic, African and being a Muslim had consequences, was when I was living in the United States during 9/11. Everything changed overnight, even with my closest friends. I became aware of my identity in a negative context. When the Egyptian revolution occurred, the opposite happened, and I began to embrace my identity. It illuminated my responsibility to understand myself in order to advocate for my people properly. It also instilled the importance of our collective story and the vital role it plays in connecting us. I began to cherish my identity and center it in my practice.

“The Longing Of The Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken” is a collaboration with the Jebeleya community, one of the biggest tribes in Sinai and Egypt generally. They have inhabited Sinai for more than 1400 years and survived wars, colonialism, drought and pandemics. Most tribes are distributed all around the country, but the Jebeleya are unique in that they’ve remained in a specific area in South Sinai called St Catherine's. It's a natural and religious history site that’s home to a treasured monastery, and for decades the community has protected monks and tourists who make pilgrimages there. It's also believed that my ancestors were Jebeleya, so it's incredibly significant to me that I've been drawn to this community.

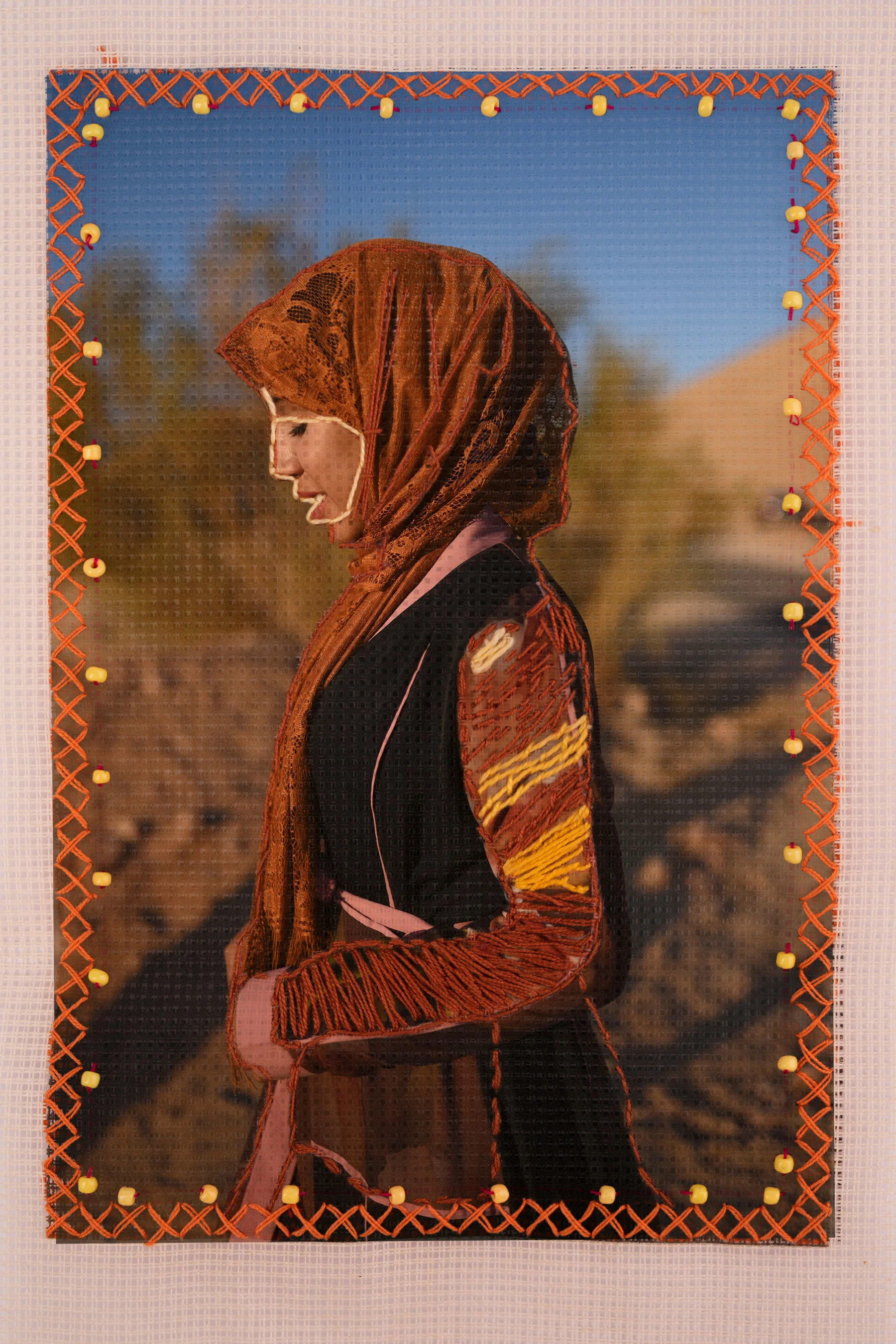

What began initially as an exploration of my identity developed into a broader exploration of belonging. Over time, I realized this was not just my story – it was the community's story, and it had to be told collaboratively. We began through conversation; we would talk about belonging and their lives as Bedouin in contemporary times. I didn't decide who to photograph; every individual made the active choice to participate. Most of the portraits are of people I have deep connections to.

When I discovered the truth about my ancestry, I found home. There are bitter feelings as well. I knew, no matter how much I integrated into the community and understood my personal history, I had not been brought up there, which left me feeling like a stranger somehow. I realized over the years that I had to respect those feelings and make peace—strengthening my connection to the community by respecting my position. I can't speak on their behalf as I'm not a full Bedouin, and that's okay.

Over time, I realized this was not just my story – it was the community's story, and it had to be told collaboratively.

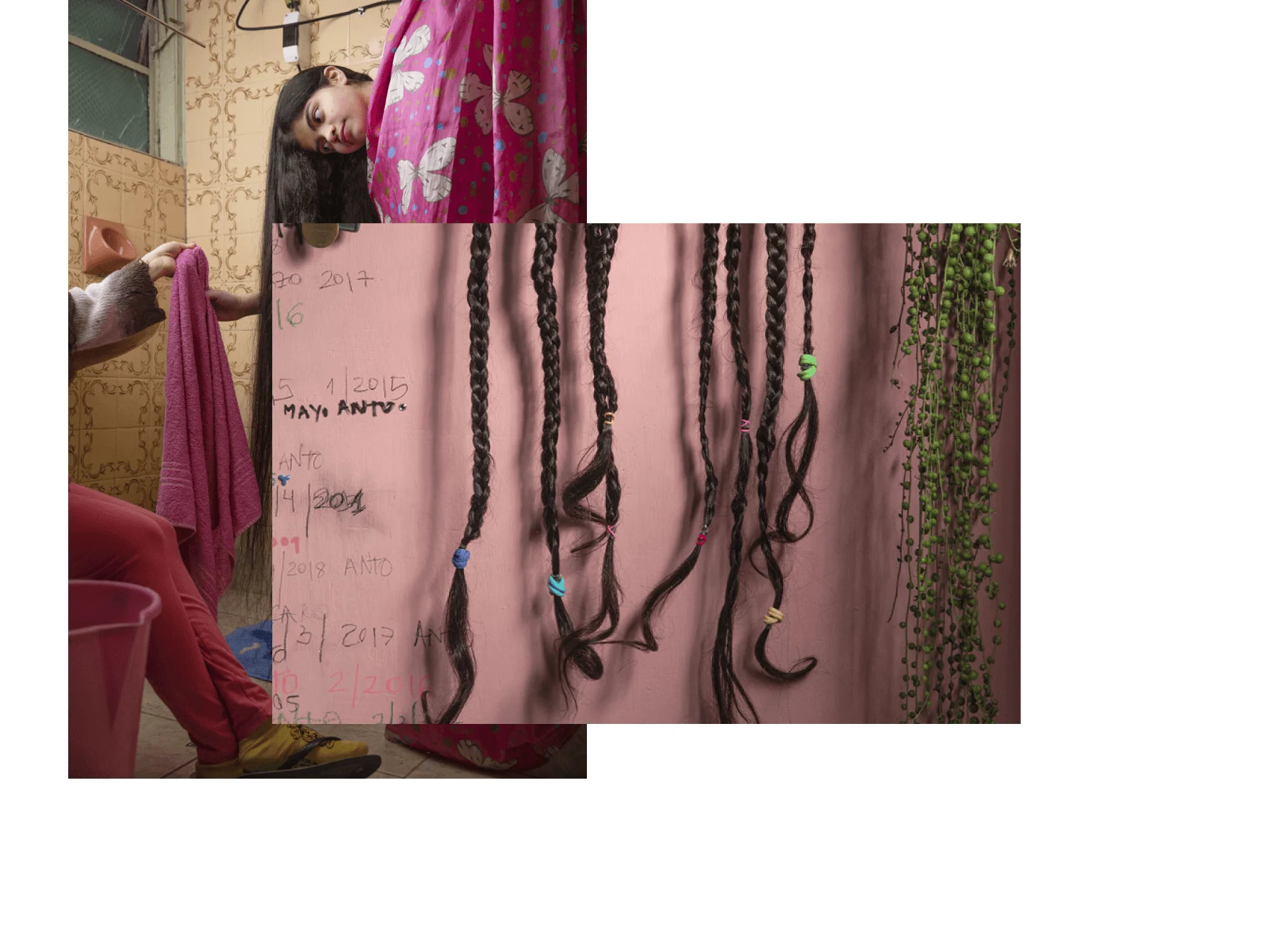

The project took off when the community started participating visually. I was struggling to involve the female voice in the project. Many Bedouin women are wary about being photographed due to the harmful stereotypes that they are voiceless and don't have a hand in their fate. In truth, Bedouin women dominate their communities, working every day to support their families. One day, when I was sitting with Hajja Rabe'aa, she asked me to draw her instead of taking a photo, and it just clicked. I decided then that I would print the photographs on fabric, and the women could embroider over it. Embroidery is a traditional medium in the culture, and that way, they could have complete control over what to show and what to hide.

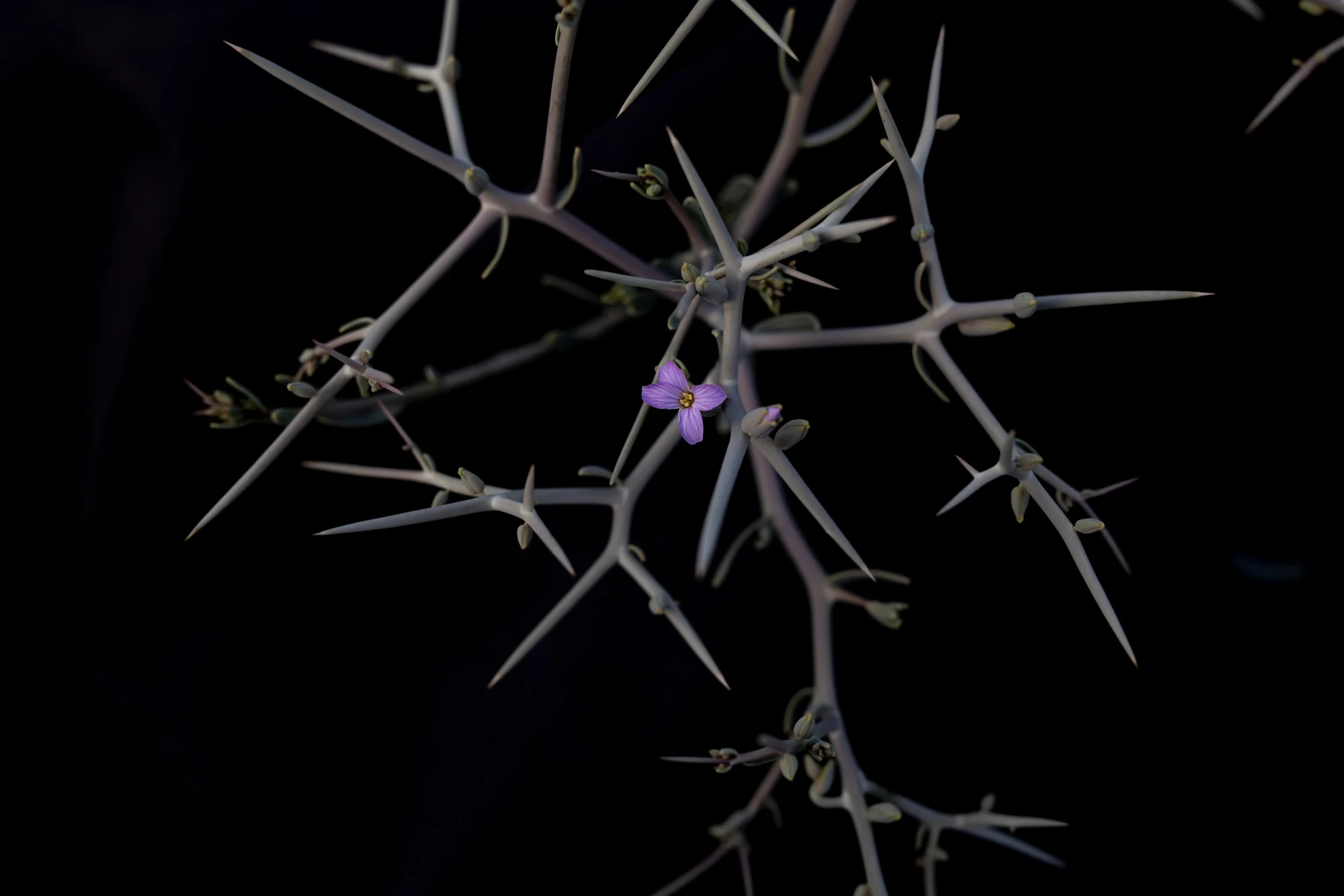

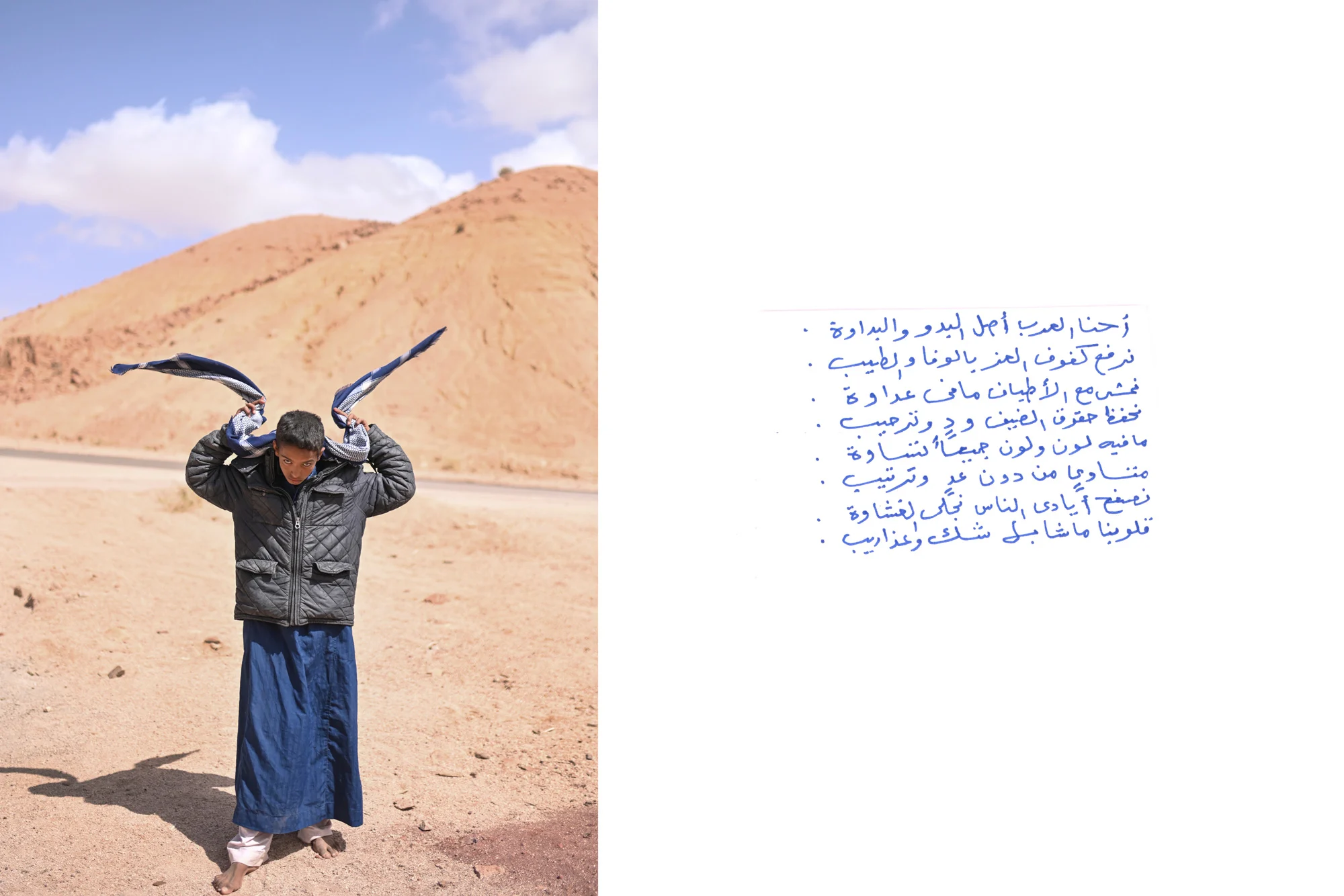

Text also plays an important role; poetry is a daily practice in the community. It’s how you express your emotions and love for one another, and many of the men contributed handwritten poems. The elders' sense of belonging is deeply tied to their land, so they compiled handwritten information about Sinai flora and fauna. This has evolved into a field guide, in which we’ve been documenting plants and their medicinal and traditional use. This guide is being distributed to the younger Bedouin members to create a bridge between generations, hoping that they will remain connected to the land.

Collaborating with the community has been liberating for me as a practitioner. I no longer consider myself a traditional documentary photographer, but rather a visual storyteller. I want to challenge this documentary form as I don't believe it’s how we’re meant to tell stories. I'm still a lens-based artist, but life is a lot more colorful when I collaborate with community members.

We all have a need to belong and this project enabled me to be comfortable in my skin. I feel that as things escalate, whether it's because of conflict, war or climate change, we are becoming more disconnected. As a visual storyteller, I see my role as contributing towards the act of reconnection, whether that's reconnecting people to the land or each other. I want to use stories to continuously create connections.”