Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around. Each year, we meet a winner from each region and hear, in their own words, what went into capturing every monumental shot, from beautiful scenery to watershed historical moments.

This year, we’ve selected a story that shows indigenous communities struggling against the onslaught of the climate crisis, a project shining a light on the disillusionment being felt by Tunisian youth and a series offering a deeply moving perspective on life and death, among others.

Six photographers, six incredible stories from around the globe. We’ll leave you to dive in.

Zied Ben Romdhane, Tunisia

“The Escape” for Magnum Photos, Arab Fund for Arts and Culture

Region: Africa

The end of Tunisan President Zinedine El-Abidine Ben Ali’s dictatorship in 2011 promised an era of freedom and opportunity, yet for many in the nation—particularly the young—the restrictions of dictatorship were merely exchanged for political uncertainty, economic crises and angst. Zied Ben Romdhane’s ongoing work, ‘The Escape’, is a visual exploration of the nation’s youth in an age of uncertainty.

“In 2022 I started photographing extensively in Tunisia’s big, coastal cities—particularly Tunis, Sfax and Sousse. While working in these large, dynamic cities, the idea for ‘The Escape’ came about.

Talking to people in the cities, particularly the youth, a big issue became clear: to many, the youth of Tunisia today have everything. Now the dictatorship is gone, young people have opportunities, freedom of speech. They can experience the dynamism of democracy. To me, this represents an opportunity, but many of the youth don’t see it that way, and that’s interesting.

Of course, there’s always a generational gap. My father or grandfather would have said my generation had more opportunities than theirs. I was aware of that dynamic from the outset, so I wanted to understand how Tunisia’s youth feel about their situation. When I was in my 20s Tunisia was under a dictatorship. Life was monotonous, boring. It was binary: you could be for or against the dictatorship. The way was clearer, the route simpler. You study, then you plan your future. Now it’s far more complicated.

The impression I got was that the youth, particularly, are really struggling with feelings of instability. When you are young and searching for identity, trying to see your future, it feels hopeless when you have a new government every six months, when there are endless debates and a toxic political environment. And it’s not just the youth—people are trying to escape the country, either physically or psychologically.

When you are young and searching for identity, it feels hopeless when you have a new government every six months.

The numbers are bad...Statistics show that a lot of Tunisians are depressed, or have been. About five years ago we started hearing a lot about very young people, 13 or 15 years old, dying by suicide. There is a malaise—that’s the term I would use for it. Seeing this malaise among the youth was bizarre for me. Talking about mental health or depression was never a thing for my generation, we didn’t have the language, the words. It’s related to this new way of life, this new way of living. It was shocking to me.

‘The Escape’ is about the general mental health of Tunisia, this feeling of malaise. I was in contact with young people with mental health issues, and while some of them are featured in the project, I don’t want to nominate them as an illustration of the issue. Maybe in one or two photos you can see images relating to auto-mutilation, but visually depicting a state of mental health is very hard. I tried to portray the situation in a broader metaphorical way. The project is not illustrative. It’s symbolic. I am trying to create images which translate these country-wide feelings.

While I am not really optimistic about the state of the country, it’s only been a short time since things changed. One hundred years for a nation is nothing, but for a person everything in their life can be determined in just ten years. The scale of time for a country is not the same as it is for a human.”

Rena Effendi, Azerbaijan

“Looking for Satyrus” for VII Photo, National Geographic Society

Region: Europe

Rena Effendi has spent three years documenting her search for Satyrus effendi, a rare butterfly named after her elusive entomologist father which can only be found in the reaches of the Azerbaijan-Armenia border. Retracing his steps, Effendi pursued her father’s fading legacy, witnessing the destruction wrought by decades of conflict and the humanity that’s weathered it.

“About eight years ago I was reading about my father on Wikipedia and learned that a species of butterfly, Satyrus effendi, had been named in his honor. It was discovered in 1989 by a Ukrainian entomologist called Jurìj Pavlovič Nekrutenko. My father passed away in 1991, and though he’d probably seen a sample, he’d never seen one alive. I became intrigued. The butterfly’s habitat lies along the mountainous border between my country, Azerbaijan, and its rival: Armenia. The two countries have been entangled in conflict for more than 30 years.

In the days of the Soviet Union my father would get on a bus, a train, or hitch a ride all the way from Baku to the mountains of Nakhchivan to collect butterflies. He would travel across Nagorno Karabakh and enter Nakhchivan through Armenia, hunting along the Zangezur ridge. The terrain through which my father passed, then beautiful and full of life, is now devoid of it.

My idea was to retrace his footsteps and to find the one butterfly he’d never managed to catch. It’s an extremely rare and endangered species. After I explained the project, the Armenian government gave me permission to visit and I went there twice to meet with Parkev Kazaryan, my father’s friend and protege, whom my father taught how to collect and preserve butterflies. Parkev caught Satyrus effendi on the Armenian side of the border in 1991, the same year my father died. I followed Parkev, but did not locate the butterfly.

On the Azerbaijani side of the border in Nakhchivan, it took me seven hours to climb to the habitat, where the species had been found before. Once you are 3100 metres above sea level there’s relentless wind, harsh weather and the land is barren.

Pursuing this butterfly was a way to learn about my father. For him nature had no political boundaries.

It’s been a difficult journey of three years, navigating challenging political terrains as well as the landscape. Pursuing this butterfly was a way to learn about my father, but also to look at the conflict. I wanted to tell its story from the vantage point of my father’s effortless journeys across these borders. For him nature had no political boundaries.

In making the project I grew more sympathetic toward my father’s obsession. I went for answers and I got more questions, but I learned to be OK with that. He became almost a mythical character. I photographed his collection, including a butterfly that he’d hunted for seven years—none of his marriages lasted that long. I opened these wooden drawers, and in some there were just labels, pins and dust remaining. His legacy is vanishing.

The contrast between his journey and mine shows the absurdity of the war. I travelled to areas where people consider someone like me–an Azerbaijani–an enemy, yet they helped me and showed me kindness. Once, in Armenia, I was surrounded by 10 or 15 people all looking for this butterfly. In Azerbaijan a whole village kept asking me whenever they saw me, “Did you find it? Did you do it?” Everyone, from politicians to shepherds, knew about this butterfly. They had all become infected with this pursuit. These sorts of human stories transcend the rhetoric and division of war.”

Naigong Wang, China

“I Am Still With You”

Region: Asia

In 2019, at the age of just 36, Jiu'er was diagnosed with terminal cancer. After years of endless treatment, she decided to leave the hospital and return to her hometown to “face death calmly.” Jiu'er’s final wish was to document her journey—through intimate images and texts—and make a guidebook for life that could offer her children insight and connection after she was gone. Together with photographer Naigong Wang, they recorded this emotional and spiritual time, highlighting moments of play, care and resilience, as well as companionship and growth, to illuminate Jiu'er’s belief that dying can also be an act of living.

“In Chinese culture, it’s very taboo to talk about ‘death.’ The traditional belief is that when a person dies, everything must be burned. One photo of life is enough. The older generation believes it’s not only futile to photograph the terminally ill, but also really unlucky. We are a people unprepared for death; afraid, fearful and unwilling to explore it. But the fact that we don’t talk about it doesn’t mean that it won’t happen, nor does it mean that we don’t have these things on our minds; death is inevitable.

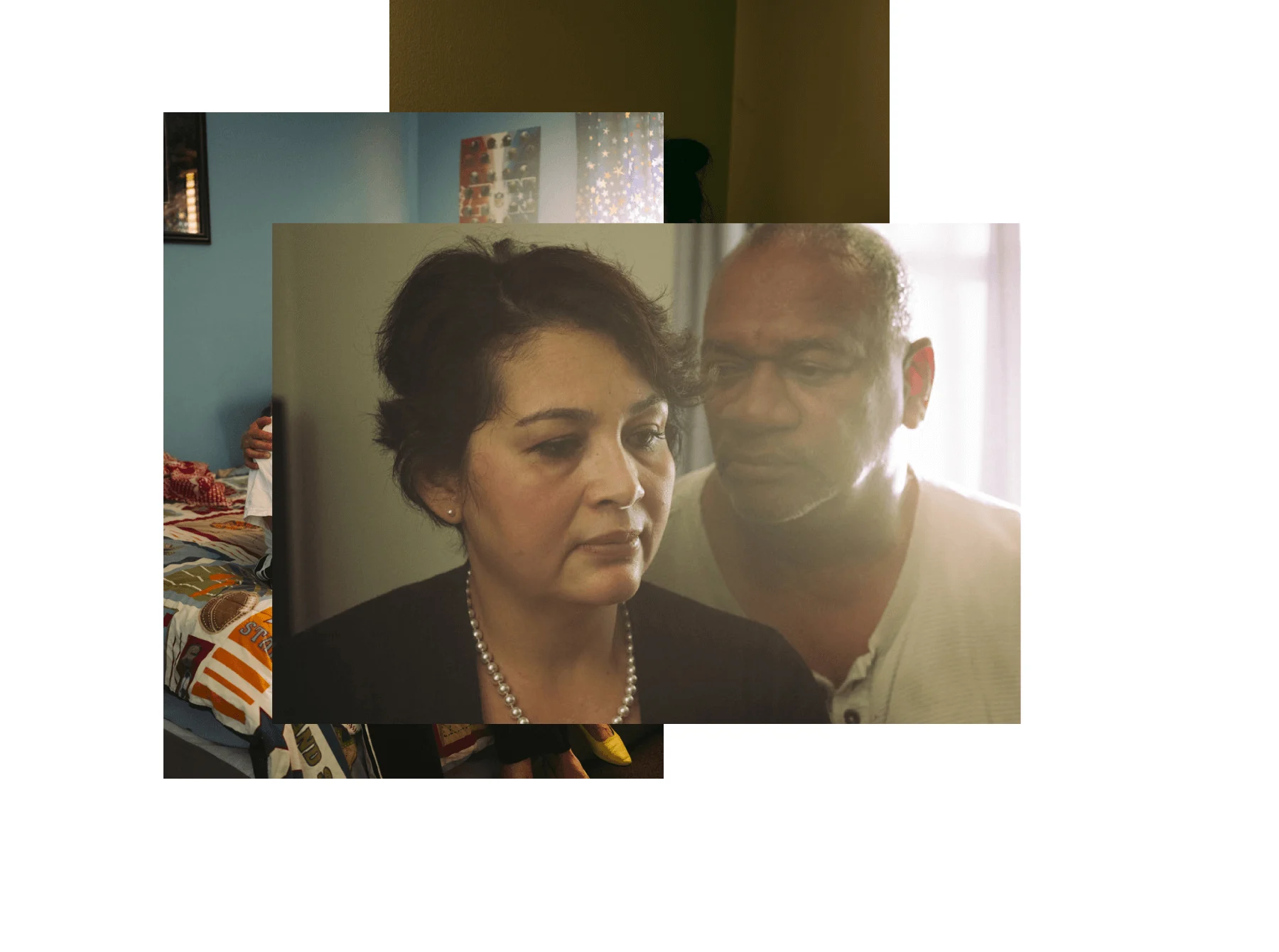

I first photographed Jiu'er in March 2019. She wanted me to take a formal family portrait before she started her cancer treatment. Jiu'er’s active treatment included one operation, 10 radiotherapy sessions, and more than 20 sessions of chemotherapy. When she learned of the irreversible outcome of her condition, she returned home to face death calmly, maintaining stability for her family and normality for her three children.

Jiu'er was not afraid of death but more worried about not being able to accompany her three children as they got older. As her health worsened, she invited me to record her time with her children. These photographs revolve around Jiu'er as the protagonist and capture her personality, life and opinions. Each photo speaks to a habit, a fragment of time and a summary of years. “I Am Still With you” is a book about love as much as it is about tragedy.

Death is neither grand nor gloomy; it’s just an end point we all must experience.

It was essential to Jiu'er that ‘suffering is not in vain, but has a greater meaning.’ She chose to be brave for love. Living together day and night under the same roof, the three children only knew that their mother's health was getting worse by the increased time she spent in bed. Jiuer made sure they did not feel the torment of her illness. They ate all their meals together. She never moaned about the pain. It was all about showing a graceful attitude towards death through her actions. Jiuer used her own actions to display courage and grace in the face of death.

My intention with this work is to reduce people’s sense of distance from death and allow them to access it with a more peaceful attitude. I believe it's not only birth or joy worthy of recording. Pain, aging, and death are also significant and hold a reverence for life. Death is neither grand nor gloomy; it’s just an end point we all must experience.

Facing a life that is gradually dimming, you only need to follow one principle: respect. Working in large-format allowed me to slow down, think deeply about the work, and explore life's essence. During this time, Jiu'er and I grew together. She allowed me to discover the greatness in ordinary moments and overcome my fear of death. Jiu'er had such a unique attitude towards life; she deserves to be seen.”

Eddie Jim, Australia

“Fighting, Not Sinking” for The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald

Region: Southeast Asia and Oceania

The climate crisis is hitting islands in the Pacific hard, as rising sea levels erode coastlines, inundate the land and poison crops and water supplies, and as changing weather patterns intensify storms. Eddie Jim traveled to the remote Kioa Island in August 2023 to photograph the locals’ predicament and document their fight for justice and aid from the global emitters.

“I’m a staff photographer at the Melbourne-based newspaper The Age and their sister newspaper The Sydney Morning Herald. Greenpeace Australia approached the Herald to suggest the organization help a journalist and a photographer visit Fiji while the Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration meeting took place. The writer Miki Perkins and I traveled the last leg of the journey on the Greenpeace Rainbow Warrior, and stayed on the island for a week.

Kioa Island is very small—only a few hundred people live there—and Miki and I spent many hours speaking with the community. Lotomau Fiafia was one of the elders. He was born on Kioa in 1952 so had seen many changes, particularly the rising sea level. He was very concerned about his people’s voice, that nobody from the outside world would care about them because they are such a small and remote community. He welcomed the opportunity to speak to the media to get their story out, and Miki and I promised to do our very best to draw attention to Kioa.

Fiafia mentioned that in his youth the shoreline had been much further out, so I had the idea to photograph him in the water to show the difference between then and now. He was also very concerned about the next generation, so asked if he could bring his grandson John along. I realized it would be good to show them together, to suggest something about their future. I wanted the image to reveal the sheer depth of the water. If I just photographed above the surface, it would be an average portrait of two people in the ocean. Showing below the surface in the frame suggests something of what they are facing.

I took this photograph twice. The first time there was a little bit of wind and it was overcast, and the image was just OK. But the second time the ocean was completely still, and flat like a mirror, and it was sunrise. I thought that could make for something quite special. We had to move very slowly—I had to ask John especially to move slowly—so that we didn’t disturb the water. The light on their faces is the light from the sunrise reflecting off the surface.

They’re concerned that nobody from the outside world will care about them because they are such a remote community.

John and Lotomau are wearing special ceremonial dress because there were guests on the island. People from all over the Pacific came to the Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration to discuss how to fight against climate change, and the support they need from countries such as Australia, for example, when they have to rebuild their houses. One of the other people I photographed was Esther Tulupe whose family had to abandon their home for higher land.

The title of Miki’s article was “Fighting not sinking” and the people of Kioa Island are not just sitting there. The Pacific Island countries want to make a statement, and have taken their call to action to the UN climate change conferences.”

Mackenzie Calle, United States

“The Gay Space Agency”

Region: North and Central America

The Gay Space Agency by Mackenzie Calle confronts the American space program’s exclusion of openly queer astronauts. Divided into two parts, the multimedia project—a surreal assemblage of photography, film, archival documentation, data and collage—offers a critical history tracing how the LGBTQ+ community were marginalized by NASA while simultaneously imagining a diverse and accepting future in space.

“As someone who has always been interested in science and space, Sally Ride—the first American woman to go to space—has always been a role model for me. When I found out she was queer in 2021, it sparked my interest in NASA’s history. Her sexuality did not become public until 2012 via her obituary, despite her 27-year relationship with Tam O'Shaughnessy. When I started to look deeper into Ride’s life, that’s when I found out that NASA’s Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts were required to take two heterosexuality tests [the Rorschach Inkblot Test and the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule] as part of their screening. If you were suspected of being gay, you would not have been selected.

I started working with the NASA archives to explore the origins of the program’s historical exclusion of openly LGBTQ+ astronauts. While the archives are public domain the information about what happened is somewhat buried. I spent hundreds of hours working through the archives looking at astronaut selection, research bases, understanding who the psychologists were and their psychiatric testing.

Homosexuality was not just taboo at this time; it was classified as a mental illness in the United States until 1973. Many astronauts came from military backgrounds and from 1953 to 1973 it was illegal for any federal employee to be gay under what became known as the Lavender Scare (a mass dismissal of anyone considered homosexual from government service). During my research, I found that this exclusion persisted beyond the 70s. In 1994, NASA asked flight surgeon Dr. Patricia Santy ‘to include homosexuality as a psychiatrically disqualifying condition’ for astronauts. The psychiatric team protested, but NASA insisted.

Queer people had to sacrifice their personal life for the professional. There was no way to have both.

We can’t move forward into the future without understanding the past. It was necessary for me to show the history while also imagining where we can go from here. The second phase of the project documents aspiring LGBTQ+ civilian astronauts during their training with the nonprofit ‘Out Astronaut’. The organization sponsors one early-career LGBTQ+ scientist every year, to embark on civilian astronaut training to promote diversity in space science, both on Earth and above our atmosphere. This includes pressurized space suit training, underwater spacewalks, limited gravity experiments and flight simulations. I’ve been photographing these aspiring queer astronauts for the last two years.

It’s been quite healing to look at this history and feel closer to what individuals like Ride, who lived through the Lavender Scare, had to go through. I have so much gratitude that I can live openly. Queer people of Ride’s generation had to sacrifice their personal life for the professional. There was no way to have both.

Ride famously said, ‘You can’t be what you can’t see.’ Inspired by this statement, I wanted to bridge the diversity gap and work towards a more inclusive future by envisioning queer people in space. By traversing its edges, we can imagine a world that is not limited by anti-LGBTQ+ sentiments.”

Marco Garro, Peru

“Silenced Crimes”

Region: South America

From 1980 to the late 1990s, Peru underwent a period of armed conflict in which some 70,000 people disappeared. The LGBTQ+ community was badly affected, with individuals persecuted, tortured and even executed in the jungle, but official research into the violence is scarce—particularly its impact on trans women. Photojournalist Marco Garro Pardo and journalist Elizabeth Salazar worked for 18 months to gather stories from some of these women.

“In 2018, Elizabeth [Salazar] and I went to the Amazon to cover a story on human trafficking and a big community of trans women. There are many trans women in the cities around the jungle because often, if they come from small communities, they have been ostracized by their families and had to move away. We started working on how the trans community had been treated during the conflict, though we were also thinking of the present. Transphobia is on the rise again in Peru.

In 2003 the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission tried to research what happened to the LGBTQ+ community during the conflict, but its study only included one trans woman and the data they reported didn’t reflect her gender identity. It was recorded under the name she was assigned at birth. This denial of trans identity continues, and extends to families. My story includes a grave of a trans woman in the Amazon, for example, whose family wanted to show her as a man. They used a male name on the gravestone and a very old photograph.

In Peru, you have to fight hard to be an activist. I hope my photographs can be part of that fight.

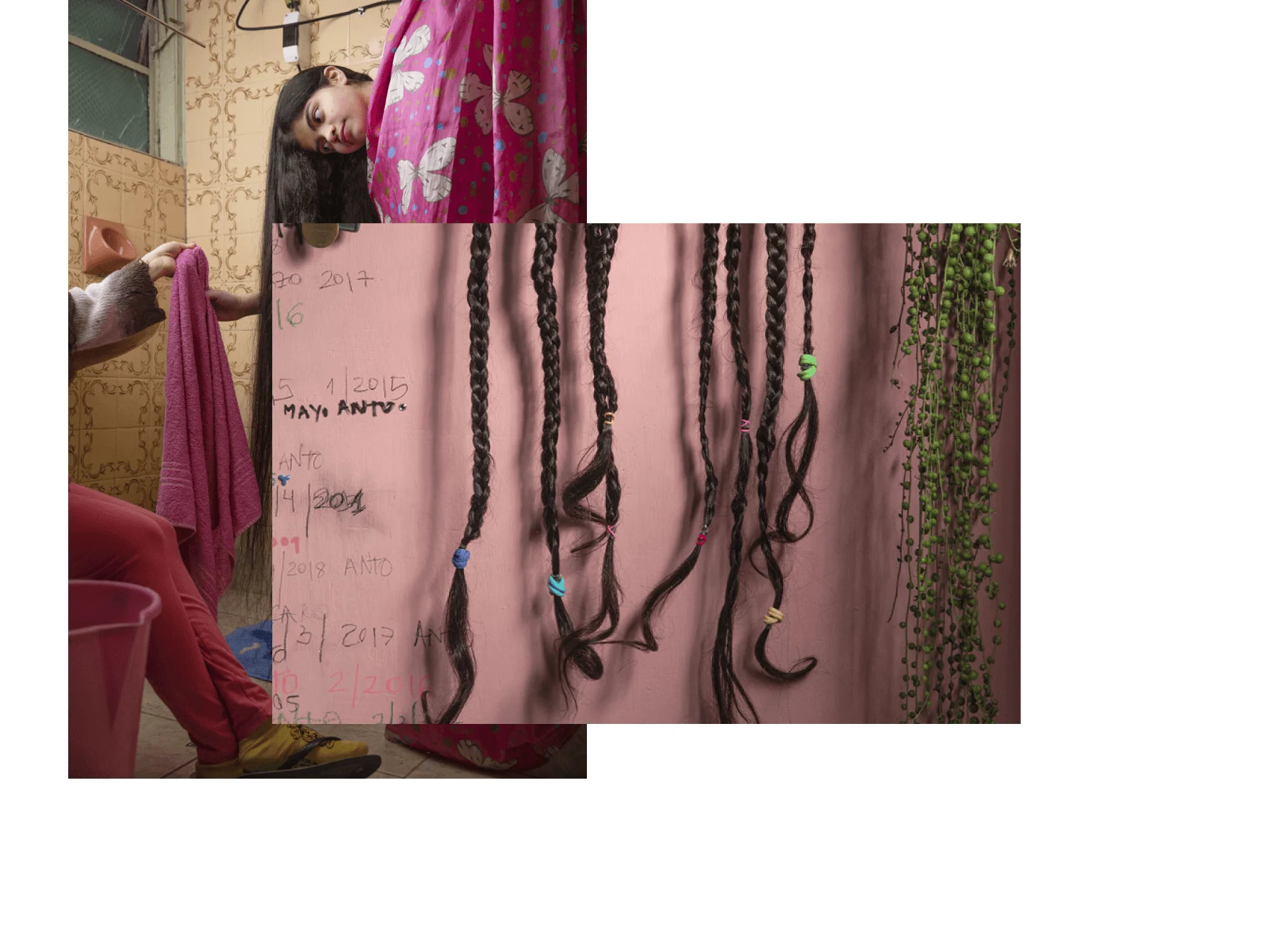

Many trans women in these cities work as hairdressers, and I found their salons very interesting. In one shot you can see a small TV which is switched off because the owner didn’t want to hear more hate speech. You can also see she has short hair—because politics have shifted further right, many of the women are changing how they look. It isn’t safe to be recognised as trans, so they cut off their hair.

We photographed one woman, Pamela, in her bedroom—the same place in which she was once attacked. It’s hard for her to stay, but she can’t afford to move, and I found it amazing she could tell us her story there. I took many photographs while she was speaking but when we finished, I asked if I could take more pictures, and she agreed. Suddenly it seemed like she was thinking about herself, not me or the interview but her life.

I have thought a lot about my right to take these photographs, because I am not part of the trans community. Many trans women in Peru are afraid to speak up. But the women I photographed were happy about the article and, after the publication of our report, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Terrorism Crimes reactivated the file into the notorious Las Gardenias crime against the LGBTQ+ community in Peru, 35 years after the massacre. In the coming weeks the case will go to trial. In Peru, you have to fight hard to be an activist. I hope my photographs can be part of that fight.”