In downtown Kabul, the modern, tidy-looking Ariana Cinema has—in spite of decades of war, terror, and regime change—survived since 1963, albeit with a facelift courtesy of the “Un Cinema pour Kaboul” association in Paris and the AINA Afghan Media & Culture Center in 2004. On August 15, 2021, the Taliban’s lightning summer offensive culminated in the taking of the city, and the group’s leadership swiftly moved to impose new rules. One of the many lesser reported results of the Taliban’s raft of new legislation was that all cinemas in the city were to be closed for business. Dutch photographer Bram Janssen photographed inside the Ariana, which has noq become a strange liminal world, one in which the cinema’s employees turn up daily to clean, staff, and maintain a cinema devoid of patrons.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers’ own words. See the whole series here.

The opinions expressed in this first-person interview are those of the photographer and do not necessarily reflect those of WeTransfer.

“I have always been fascinated by the ordinary existing within the extraordinary, by the day-to-day things that continue to happen under extraordinary circumstances.

I was in Afghanistan last year, covering stories for the Associated Press. The fall of Kabul to the Taliban was a big story, and a local colleague mentioned that the Taliban had closed all the cinemas in the city, which triggered me into action. I have, since childhood, appreciated the romance of the cinema. We drove to a few of them, but we weren’t getting lucky. People didn’t want to talk. But then we arrived at the Ariana...

The cinema has been there since 1963. If you think about what the country’s been through since then, the changes of regimes and governments, and wars it’s seen, it’s just incredible. Of course, that goes for almost everything and everyone in Afghanistan.

The moment we got into the Ariana I was just blown away. It was incredible. It was a gift, really, the place itself. The way the light fell, the colors, its dark corners, its shadows. But there was also the story that was unfolding inside the cinema: Its 20 or so employees were still turning up and doing their shifts, unsure if they would get paid or if the cinema would ever re-open.

They told me that I needed permission from the Taliban to take photos. You have to remember that the staff are municipal employees, and the municipality is now the Taliban, so, of course, I respected their request and applied for permission. The Taliban didn’t understand why we wanted to photograph a closed cinema, but we kept pushing, and eventually some four or five days later they gave in. They gave us the stamps we needed and I actually started photographing.

If you think about what the country’s been through since then, the changes of regimes and governments, and wars it’s seen, the cinema is just incredible.

It was difficult in the beginning. The staff were all very proud of the place and their jobs. They were eager to share their stories. But because of that, and there being so little for them to actually do, they were very aware of my presence. It was immediately obvious that it would take time to make them feel comfortable.

I started by shooting portraits, thinking that I could get the guys to feel more relaxed around the camera. Ultimately I spent something like six days in the cinema, spread over a longer period. The more time I spent there, the more I got to understand life in the Ariana, and slowly it gave me more of a sense of the place, of how it really functioned.

Some staff were film enthusiasts, the projectionist in particular. He loved films. I saw the spark in his eyes when he spoke about them. He was the one who told us, ‘If a country doesn’t have cinema, then there’s no culture.’ He really felt for the place and what he was doing there. I asked them all why they kept turning up. They said, ‘This is our job. What are we going to do at home?’

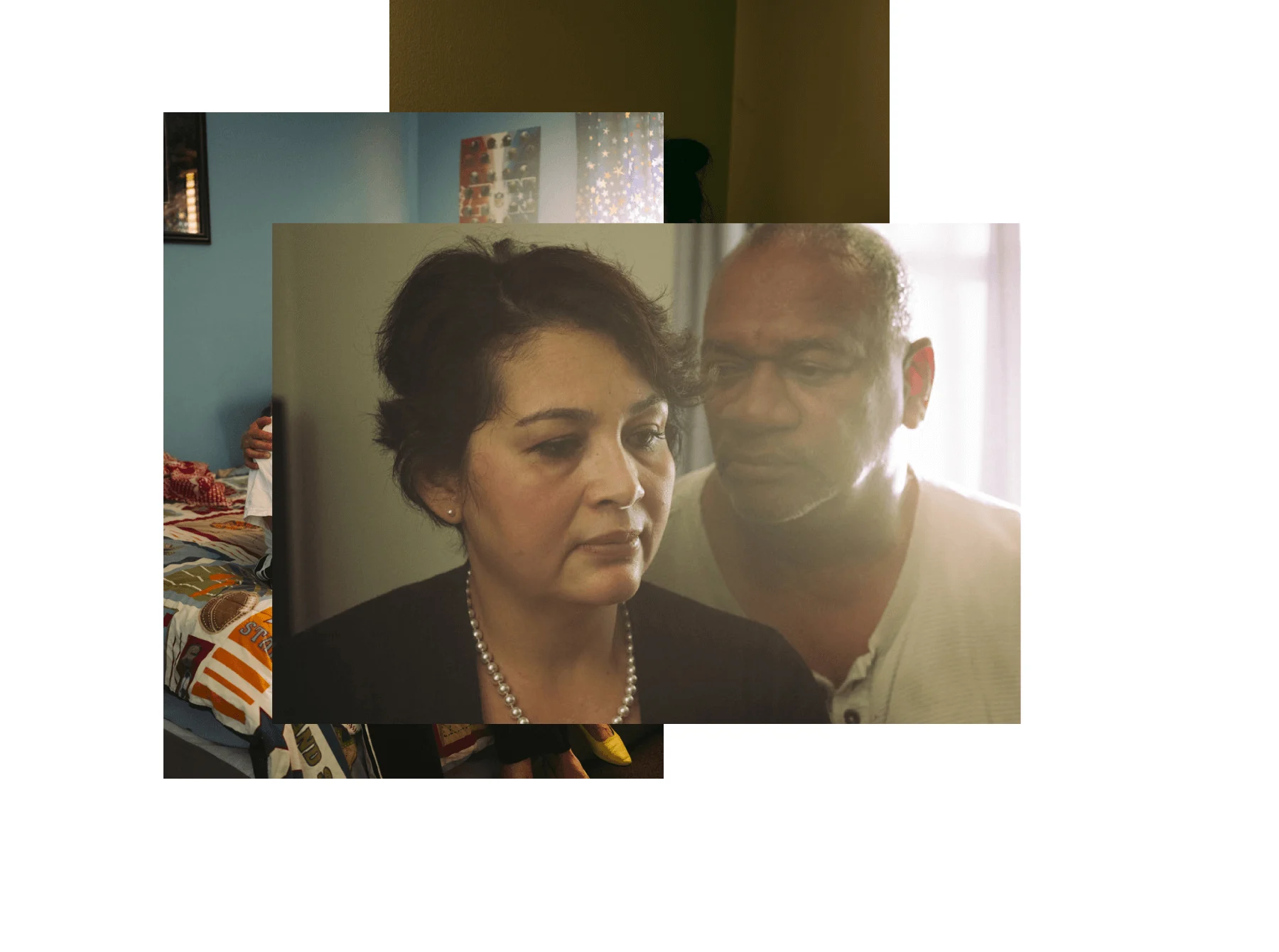

The cinema’s former director, Asita Ferdous, had been the first woman to hold the position, but until she got in touch we didn’t even know of her existence. Unlike the men, she had not been allowed to turn up for work. At first, she didn’t want to be photographed. Later, when she saw the pictures I had taken so far and she got a feel for my intentions, seeing the amount of time I was spending in the cinema, she changed her mind. She said I could take her portrait at her home. She was probably the one member of staff affected the most.

The more stories we tell, the fuller the picture we can build.

This story, her story, is the story of Afghanistan right now: the people, and particularly the women, being so deeply affected by this change of regime. I think stories like hers—and the Ariana’s—offer a slice of life, of the reality of living in these extraordinary situations. As a journalist you try to tell a story in as many different ways as you can. A story is never one-sided, never on a one-way street. There are always side streets and side stories. People might ask, ‘why are you photographing a cinema when people are dying in hospitals?’ But one thing doesn’t cancel out the other, they are all a part of the larger story and of life in Afghanistan. The more stories we tell, the fuller the picture we can build. How can we tell the story of the day-to-day life that continues within that bigger, global news story?

How do people carry these extraordinary circumstances on their backs? How do they manage to carry on with their lives in some way?

I photographed at a spa near Mosul, in Iraq, back in 2017. Soldiers would relax there during breaks from fighting Islamic State. It is the same core interest with this project: How do people carry these extraordinary circumstances on their backs? How do they manage to carry on with their lives in some way?

My approach to the photos developed as I worked. Over time this cinematic feel came through, and it just made sense. I started photographing these silent moments, the little vignettes: the rows of empty chairs, the flowers in the corner. These small scenes convey the emptiness of the place. The staff were cleaning, doing their jobs, but there was also this void, in spite of them all being there. A place—and people—in total limbo.”