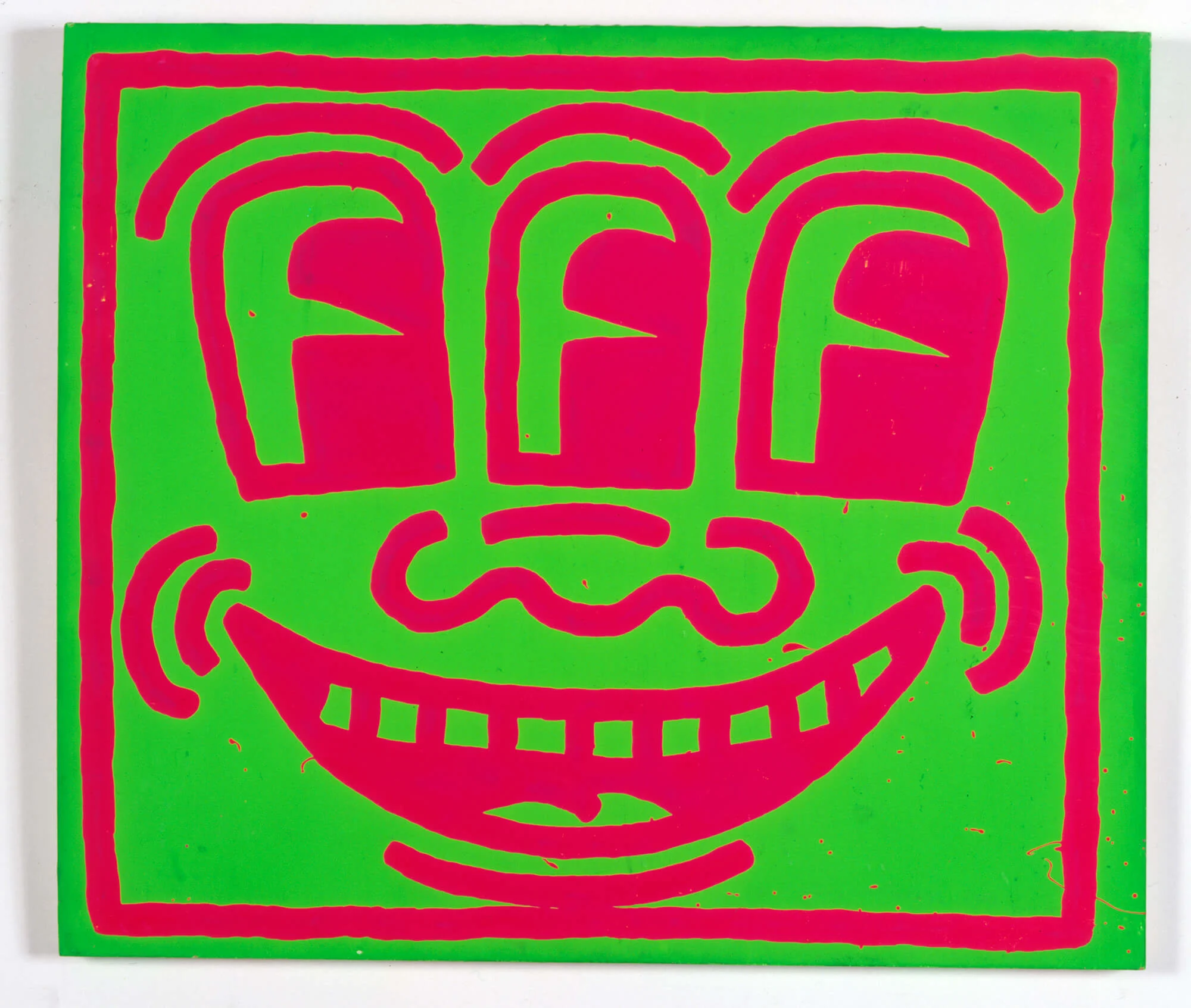

It’s the radiant baby, the barking dog and the dancing man; the badges and the t-shirts; the unmissable mural spelling out CRACK IS WACK. Keith Haring’s career was short but spectacular, and he leaves behind a lasting legacy.

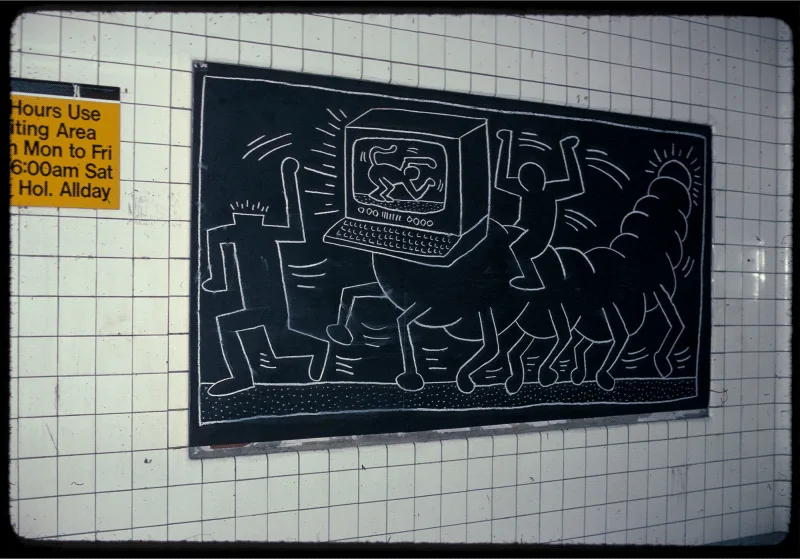

From his chalk drawings in city-wide subway stations, to his collaborations with the superstars of his day, Haring’s life was founded on a belief in the power of people to change the world. And he delivered this optimism in a burst of creative energy, as Tate curator Darren Pih explains – visual activism with a bold graphic line.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.

His upbringing was cartoons and political chaos

Keith Haring was born in Reading, a city in south-eastern Pennsylvania, in 1958, and raised in nearby Kutztown. He had a simple, conservative upbringing with his three younger sisters, infused by a love of television, Walt Disney (for whom he dreamt of one day working) and Dr. Seuss. From an early age, his father encouraged him to draw.

But his “cherry pie” childhood played out against a backdrop of huge drama in 1960s America: The Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, President John F. Kennedy and his brother Bobby, and the Stonewall riots which propelled the gay community into the headlines.

“This socio-political counterculture, the anti-war movement, and the innocent, immediate cartoon style of drawing seem to converge in Haring's work in the 1980s,” Darren says.

He helped electrify New York’s vibrant East Village

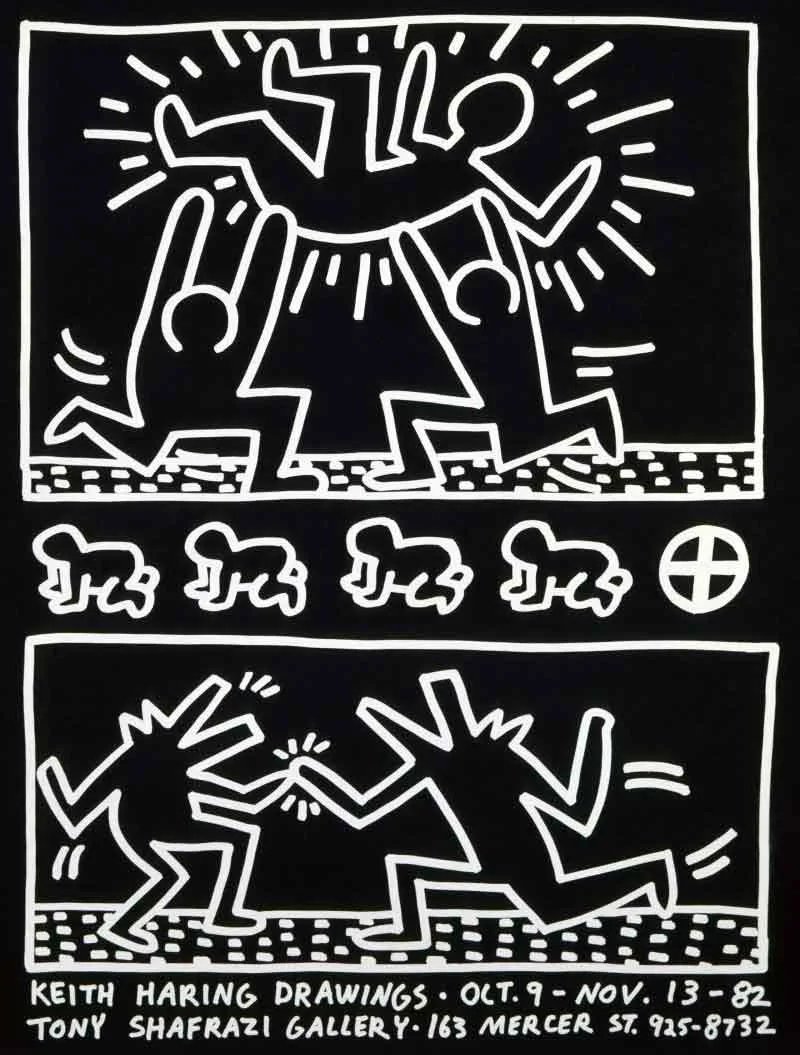

Haring briefly studied graphic art in Pittsburgh, before dropping out and moving to New York in 1978 pursue his own artistic passions. In the East Village, with its cheap rents and multicultural, sexually liberated crowd, he met people like artists Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The sheer energy and innovation of 1980s New York swept him up. He embraced his own sexuality as an out gay man, created art outside of the narrow world of galleries and museums, frequented clubs and dancehalls and curated exhibitions at various alternative spaces throughout the city.

He mixed his influences and his icons

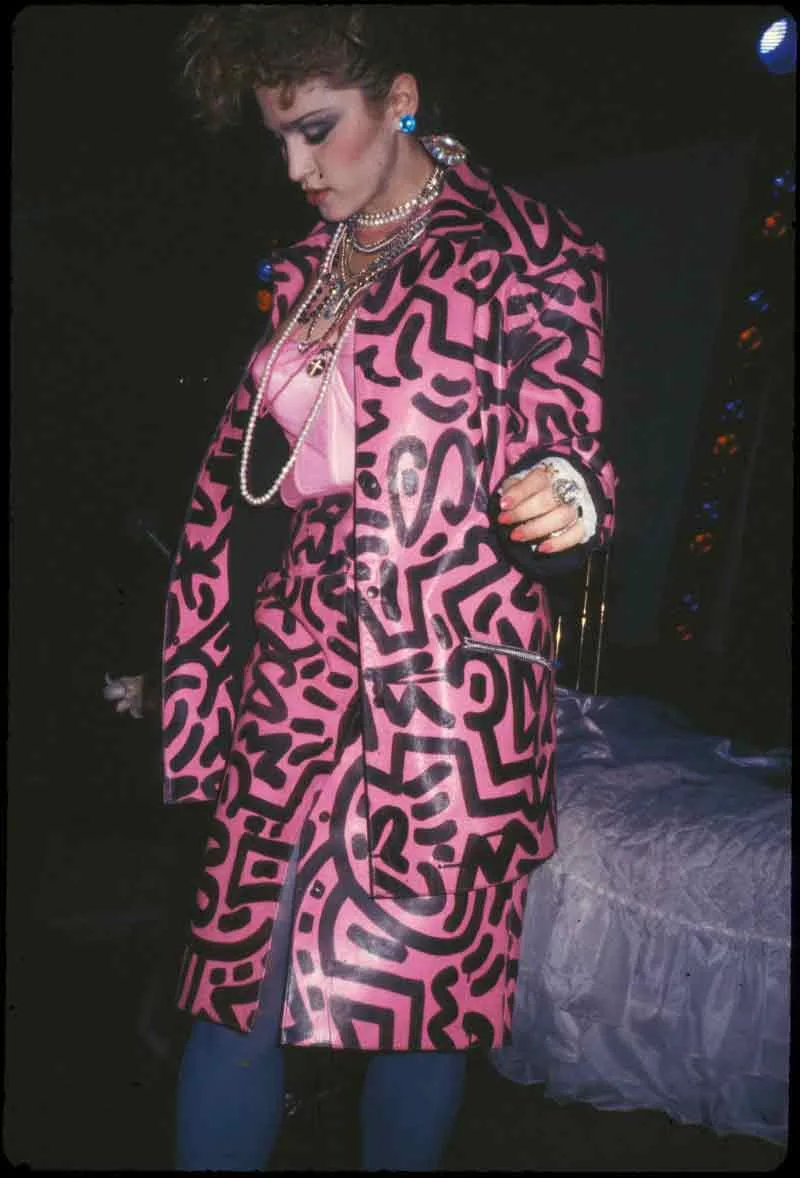

By the 1980s, the East Village was a hotbed of contemporary culture. Art, activism, style, hip-hop, robotics and computer games all came together. These things all made their way into Haring’s work; he collaborated with everyone from Madonna to writer William Burroughs, Yoko Ono to fashion designer Vivienne Westwood.

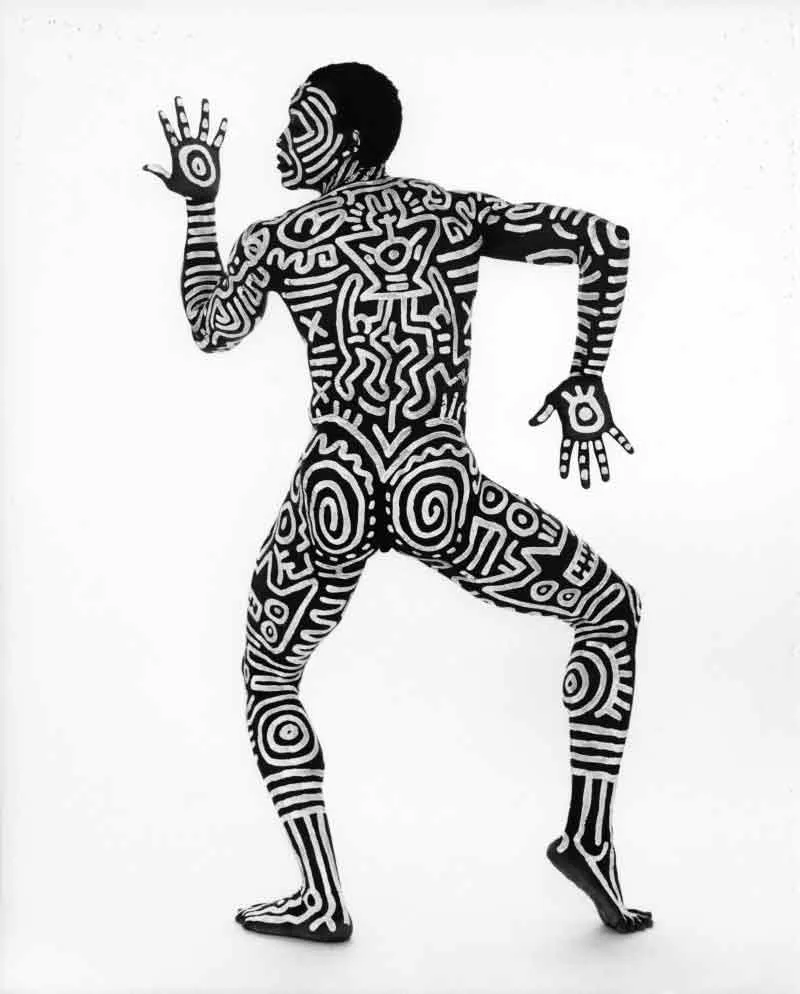

Haring met Andy Warhol in 1983, and Warhol, in turn, introduced him to Grace Jones, who he went on to paint for several spectacular performances at the iconic nightclub Paradise Garage.

Music played a crucial role in his practice, too. Legendary punk venue CBGB was just around the corner from his studio and in the 1980s, the venue was at the heart of a new wave of music, with performances by Blondie and Talking Heads. As hip-hop began to explode, Haring invited Afrika Bambaataa to play at the opening of an exhibition called Beyond Words at the Mudd Club, curated by Fab Five Freddy. “It was a living culture,” Darren says – and Haring was at the beating heart of it.

He made art in the streets – but it was never only street art

He built a language out of simple positive symbols

He captured complex political messages in unforgettable images

“There was something very innocent, unprejudiced about Keith Haring,” Darren says. He was influenced by mid-century artists like Jean Dubuffet and Pierre Alechinsky, who, in the years following the Second World War, turned to the raw, immediate energy of childlike drawings to communicate innocence and accessibility.

Haring loved working with kids, and his own childlike spirit showed itself in the clean, simple lines of his graphic pictograms: the radiant baby, the barking dog.

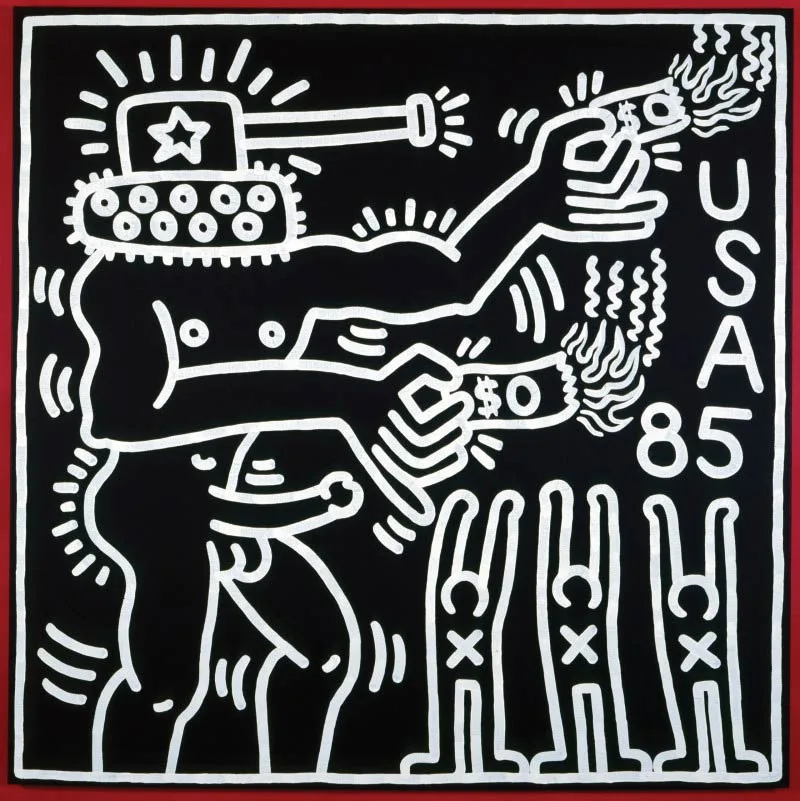

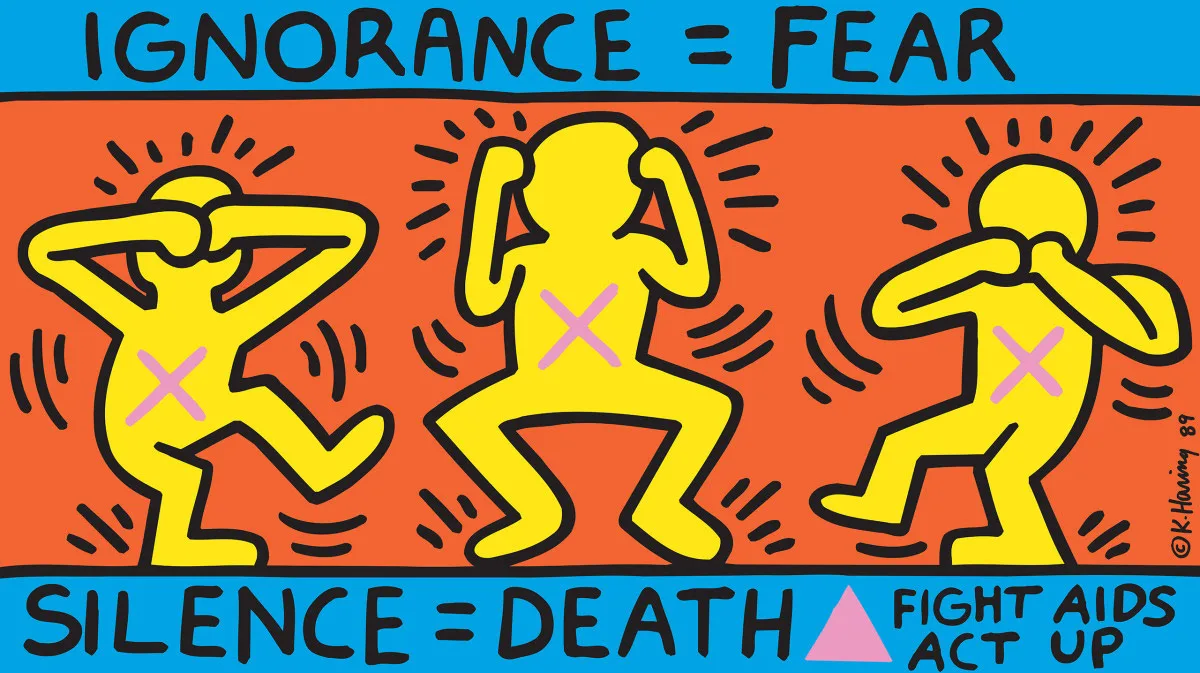

A child of the 1960s, he knew how to simplify social or political ideas into memorable and meaningful images. Working during the Cold War, the AIDS crisis and drug problems sweeping New York, he knew simple visuals and slogans could be very powerful. “He's using it in a way that speaks of his age,” Darren says. “Like an archetypal language.”

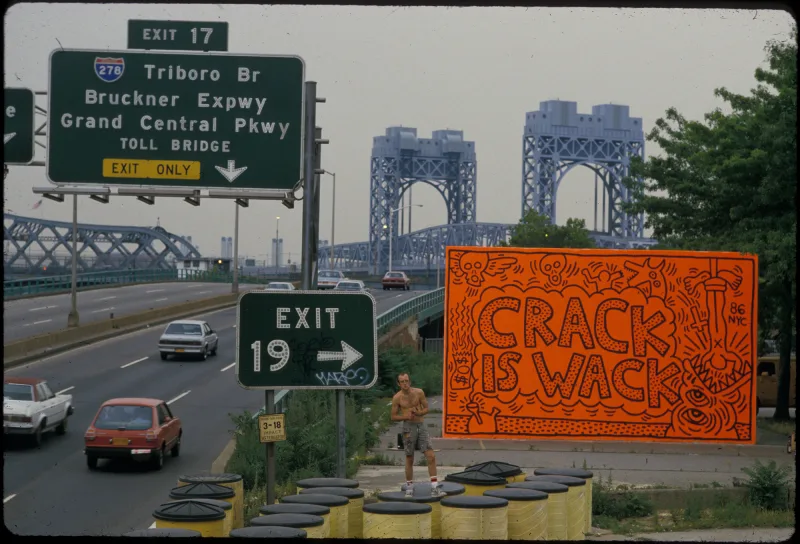

Take his 1986 Crack is Wack mural, painted on the north wall of a handball court in East Harlem, inspired by a good friend who had recently become addicted to the drug (as many would over the years that followed).

That same year he painted a mural on the Berlin Wall in the colors of the German flag. It was a vibrant call for unity in a divided city. His anti-Apartheid work, first created in 1985, would later be used as a symbol in protest marches against the South African regime.

“He was using his profile to raise awareness of issues that were affecting his city, his own immediate social circle and the world,” Darren says. “He was compelled to be a spokesperson for his generation.”

He was comfortable performing for the crowds

Haring’s trademark symbols are bursting with energy – and the artist, when creating them, had a unique energy about him too. Often beginning with a thick black frame, a reference perhaps to the cartoons of his youth, Haring painted quickly.

There was also a performative aspect to these very public works. He’d create them in community spaces, often while listening to music on a boombox, and he was completely at ease being photographed or filmed. The bigger the crowd that gathered to see him work, the more press he could expect, and the more people he could reach with his socio-political messages.

So the pieces themselves are less artefacts made to be bought and sold, but parts of a performance in which the creation itself is the artwork. When he was invited to make new work in new countries, he would go there, channeling the energy of each place into every piece.

“He would come over and make the large-scale paintings and murals in situ, because that was how he worked,” Darren says. “He wasn't just shipping works over from New York. He was leaving his trace.”

He worked tirelessly to raise awareness of the Aids crisis

He turned his art into merchandise for the masses

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.