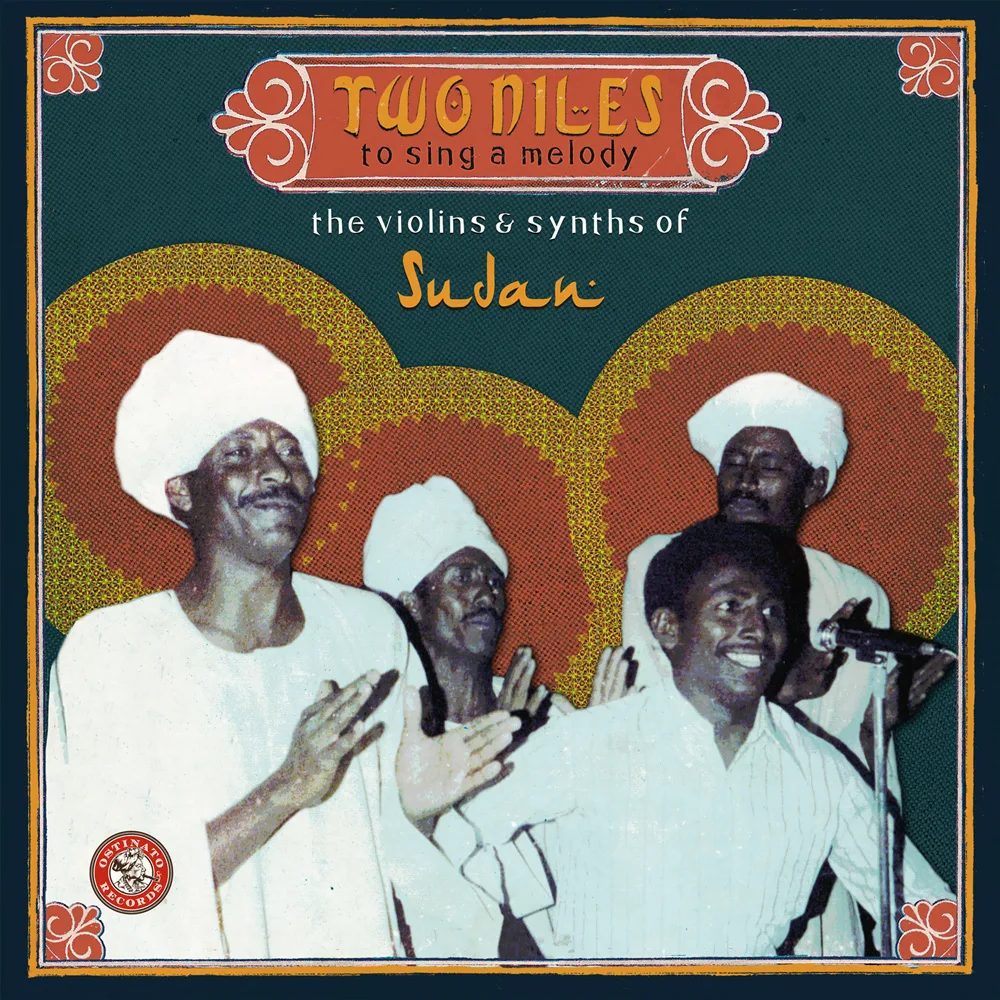

New York-based Ostinato Records is “what the truth sounds like.” Through its musical output, the label is on a mission to recover the artistic legacies of the countries and societies that have suffered everything from political unrest to natural disasters. Since he founded the label in 2016, Vik Sohonie has released long-forgotten music from Senegal, Haiti, Cape Verde, Somalia, and Sudan. Sajae Elder meets Vik to tell the story of this extraordinary label.

Born in India and growing up between the Philippines, Thailand, and the United States, Vik has always had an understanding of how identity, history, and art were inextricably linked to one another. But long before taking on the legwork of global crate digging, sounds from around the world informed Vik’s musical and political sensibilities. “The music I listened to was always Black American music because it gave me strength. It was the only music that allowed me to understand the world,” he explains. “If you don’t understand Black American and Black Caribbean history, you cannot understand the world, because that’s the cradle of what built everything. It was a gateway that helped me feel secure because that music spoke to a lot of the racism and ostracization that I was experiencing.”

If you don’t understand Black American and Black Caribbean history, you cannot understand the world.

With a background in journalism, Vik eventually grew disillusioned with the mechanics of Western media, a space where Black and brown stories, and bodies, are an afterthought. “I quickly learned that journalism where you cover other countries is not meant for me,” he explains. “Even for Indian citizens, or brown people really. The stories I want to tell are not the stories Western journalism is telling.”

I translate a lot of the anger and what I see happening in the world into the music we produce.

It was when he landed a job as a photo desk editor at Reuters that his idea for Ostinato Records saw its earliest iterations. “That was my first experience with figuring out how we perceive the world through images,” he says. “Why was it that photographers capture Europe so differently to how they capture the Middle East or Africa?” It was a question that nagged at him as he was bombarded with images that included war, famine, and death affecting the global South, handled with far less tact than images of the West. “When these outlets were covering Italy, I didn’t see a single dead body,” he says, referring to the coverage of the severe COVID-19 outbreaks there in comparison to the dire pandemic situation in India. “All I’ve seen for the last few months is nothing but dead bodies of people who look like me. It was the same thing at the desk.”

We have to treat vinyl records as physical, cultural music artifacts the same way we treat artifacts that are sitting in British and German museums.

After returning to the United States for his Master’s in Journalism, Vik courted job interviews at legacy publications like the New York Times and in municipal government press rooms. Ultimately, he turned these offers down in favor of registering the business that would eventually become Ostinato Records. “I just thought, if I combine journalism and use music – the most timeless thing there is – as a storytelling tool, I can probably have the biggest impact on what I’m trying to achieve in this world,” Vik explains. “I knew how to market the albums, but I had a bigger goal than that. It was me saying, ‘I’m going to turn these albums into global news stories.’ When you then click on the Haiti page on BBC, or the Somalia page at the New York Times, you’ll see a positive news story about the country’s music and culture and within that news story, you’re going to have me talking about the Western role in destabilizing these places. It allowed me to be subversive under the guise of music.”

For Vik, focusing on the cultural production of countries that have suffered the effects of colonialism, war, famine, and revolution, carrying with them negative perceptions from Western media, felt cathartic. “I translate a lot of the anger and what I see happening in the world into the music we produce. It’s a healthy outlet for me to say, ‘Let me expose you to beautiful music from demonized parts of the world,’” he says. “There are amazing storytellers in Africa, in South America and the Middle East and Asia, but they don’t get the spotlight that Western storytellers get.”

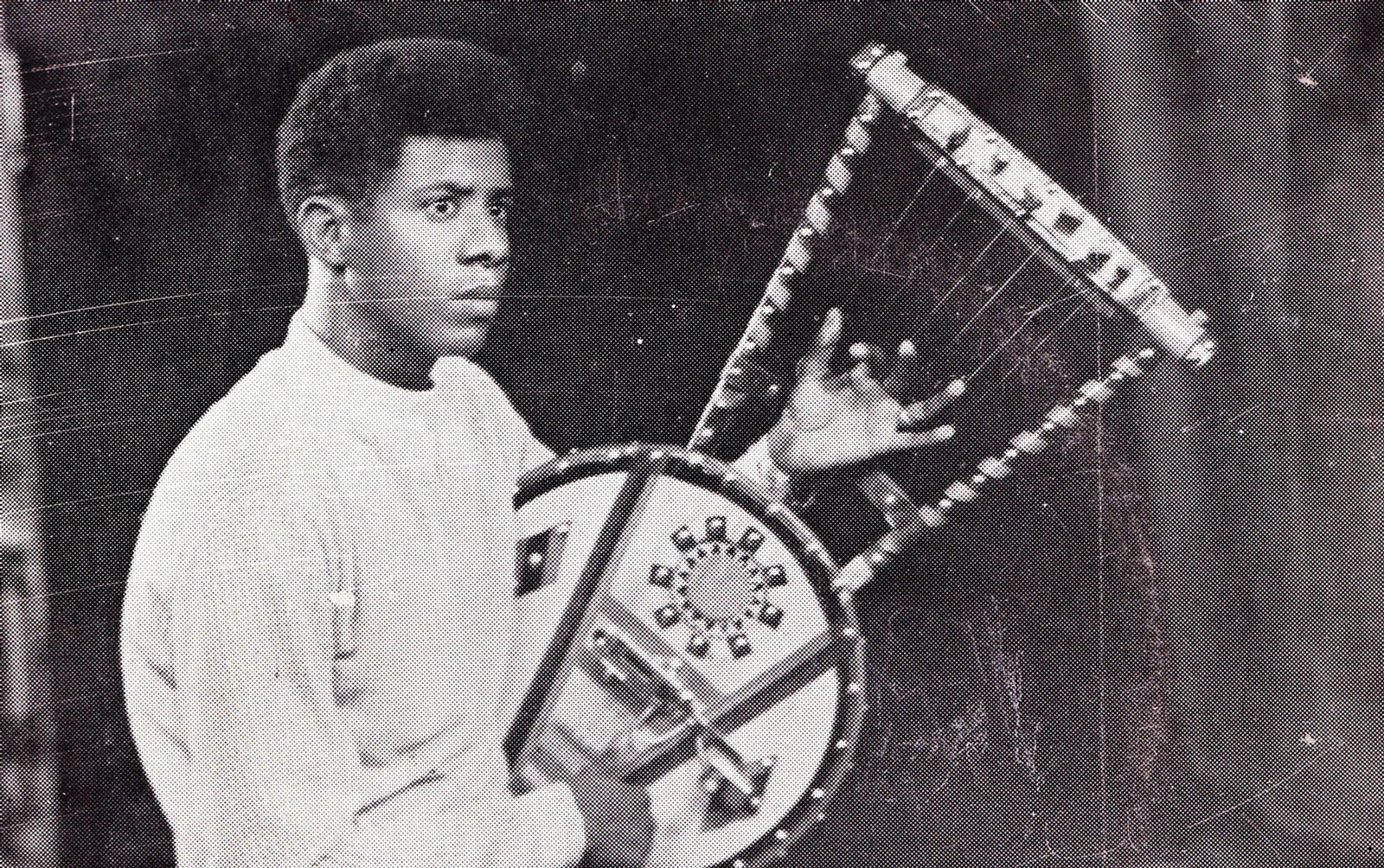

Senegal

With the label’s small but mighty team, which includes producer Janto Djassi, archivist and restoration engineer Mark Gergis, and graphic designer Pete White, taking on projects as complex as Ostinato’s requires patience, true curiosity, and a particular kind of fearlessness. Crate digging in a manner of speaking goes digital, with many of the unearthed finds coming by way of YouTube clips. “You can find all kinds of stuff because everyone is always recording and uploading older things,” says Janto. Born in Germany with Senegalese and Malian roots, he met Vik on a 2016 trip to Somaliland. “Little concerts and little gatherings. We find videos, and then we try to find contacts. Some that we already have established, or through family contacts, whatever it is.”

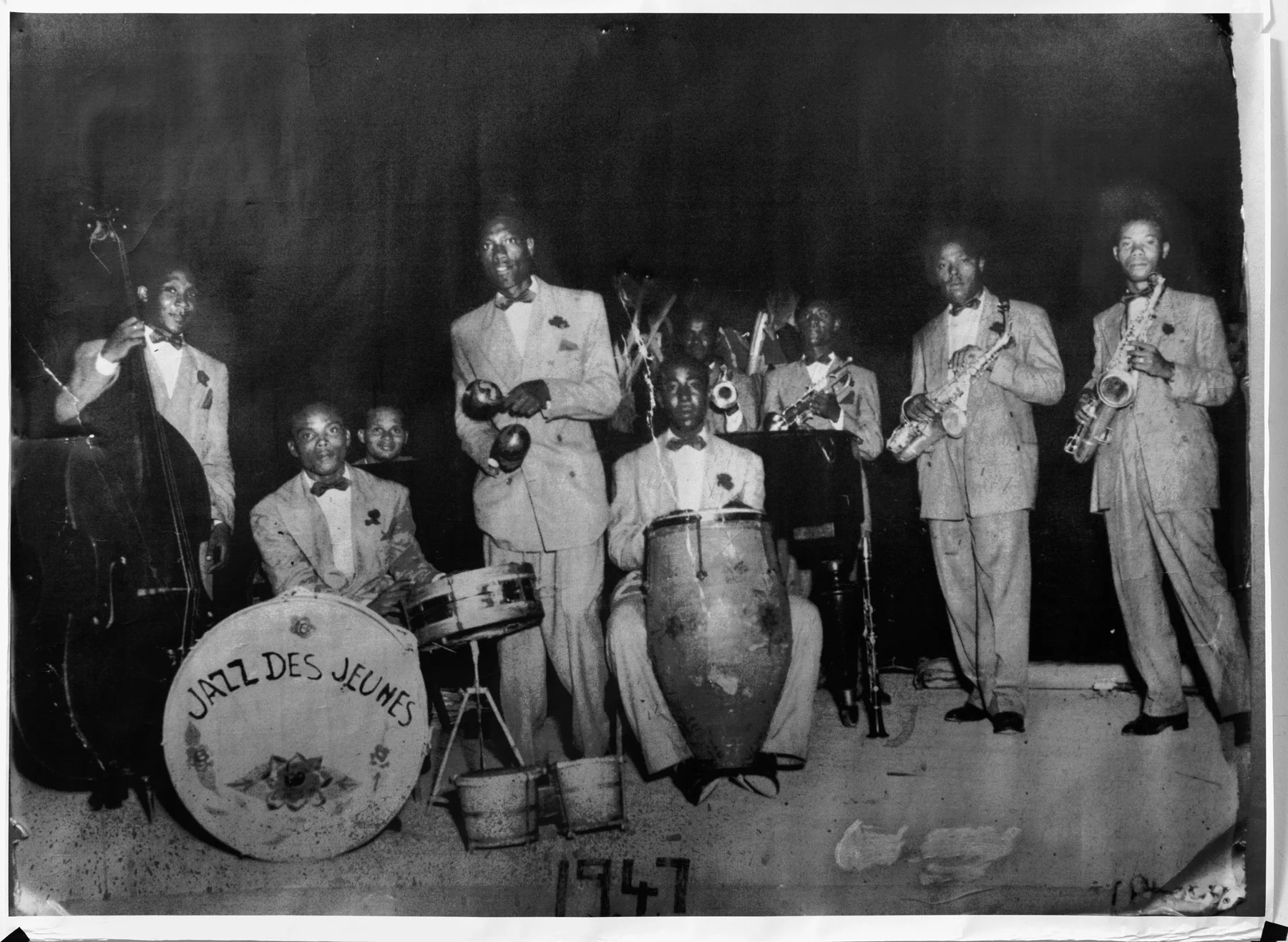

For what would become the label’s debut project, Tanbou Toujou Lou: Meringue, Kompa Kreyol, Vodou Jazz, & Electric Folklore from Haiti, Vik started by putting an ad in local newspapers, both in New York City and Port-au-Prince, Haiti. With dozens of calls and invitations to peruse decades-old vinyl collections in people’s homes, the project took shape in unexpected ways. “This is why we need more Black and brown storytellers, because we were being introduced to people who felt comfortable to say, ‘Come with us. We can see that you want the real stuff,” he explains. “To me the most real food in Southeast Asia is your back alley street food, for example. I always say I want the musical equivalent of that.”

Crate digging in a manner of speaking goes digital, with many of the unearthed finds coming by way of YouTube clips.

As the first project took shape, Vik was already starting to re-think the label’s business model with respect to the records he purchased and took back with him. For him, a nation’s cultural and historical legacy lies in its art and artifacts, which included records. “I remember going through the records and I thought, there’s something wrong here. This is not sustainable,” he explains. “You can’t just have one guy in Berlin with an entire country’s historical legacy sitting in his apartment. We have to treat vinyl records as physical, cultural music artifacts the same way we treat artifacts that are sitting in British and German museums. 95 percent of Africa’s cultural wealth sits outside the continent, and that has to include vinyl records, cassette tapes, and VHS tapes.” For each project since the first, the label has focused on digitizing their finds, leaving the original vinyl records and cassettes with their original owners, in their respective home countries.

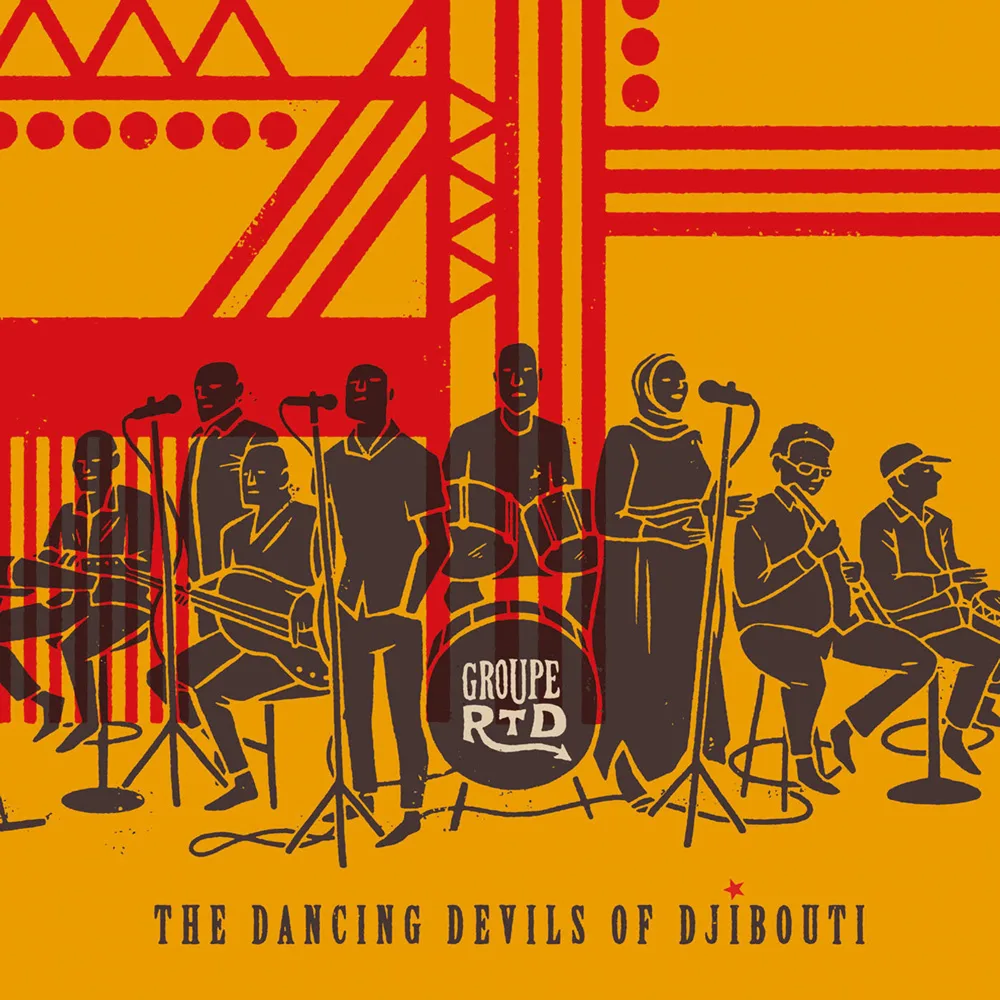

In addition to creating these digital archives of music from countries like Haiti, Sudan, and Djibouti, Vik and his team leave the equipment behind, giving these countries and their cultural entities the ability to continue the process of digitizing music, both old and new, on their own. It’s an equal opportunity partnership that gives these nations power over their own cultural productions. “The national radio archives in Djibouti are now able to digitize their stuff at the highest quality possible and in exchange, Ostinato gets a couple of albums that we get to release,” he says. “I think it’s most beneficial when everyone walks away from the table with something.” Though the label’s hope is to continue to release music from the countries they work alongside, it’s not a mandatory condition of the partnership.

For Janto, their own method stood in stark contrast to the sometimes predatory practices of labels from the West, primed to serve largely white listeners with an ear for “obscure” global music. “What we did in Djibouti with the archives made me realize that so many people who work in this business don’t take their counterparts seriously,” he says. “But we provide the technical equipment, and the knowledge that we have, in exchange for what they can contribute to this project. We want it to be eye-level.”

I just thought, if I combine journalism and use music as a storytelling tool, the most timeless thing there is, I can probably have the biggest impact on what I’m trying to achieve in this world.

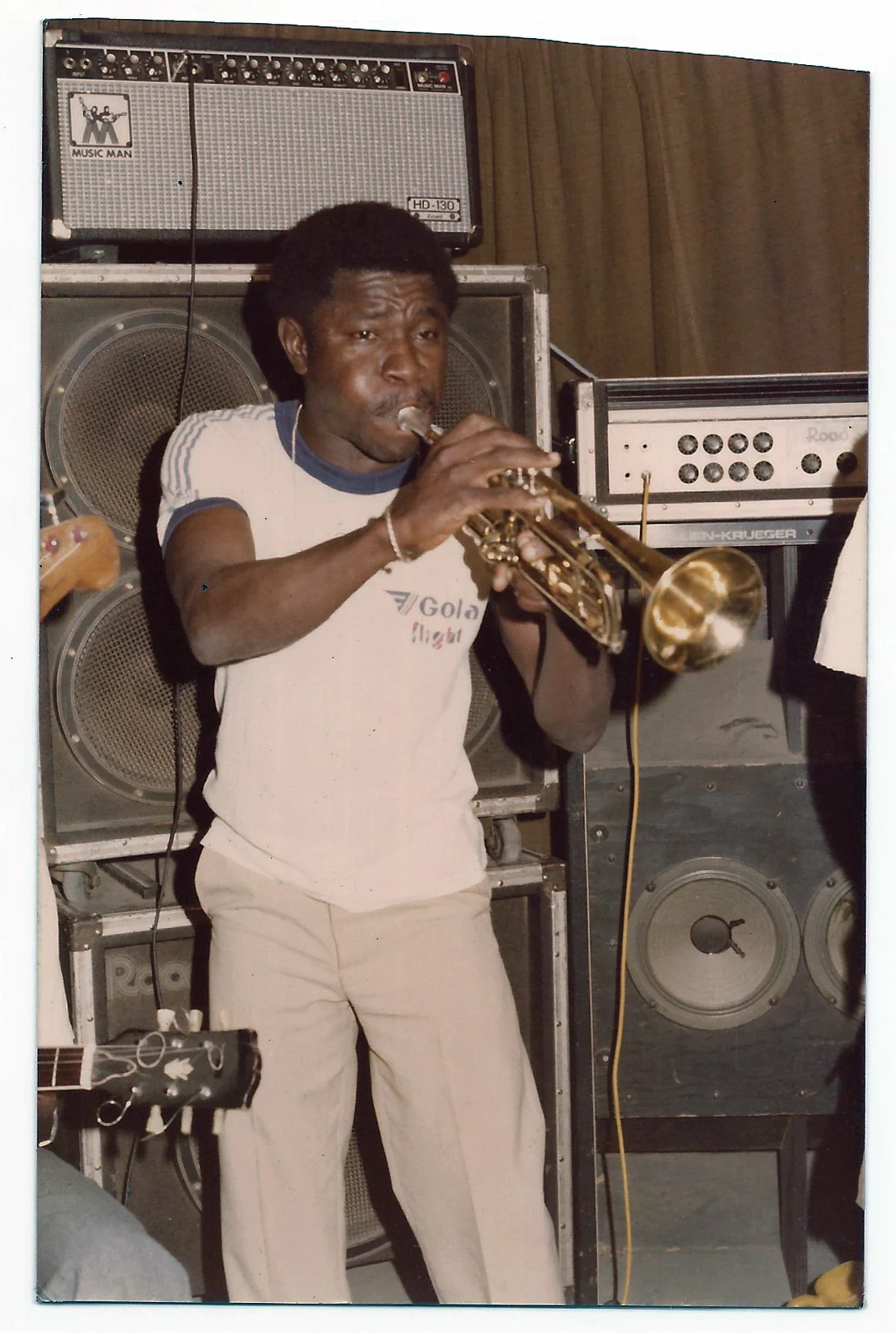

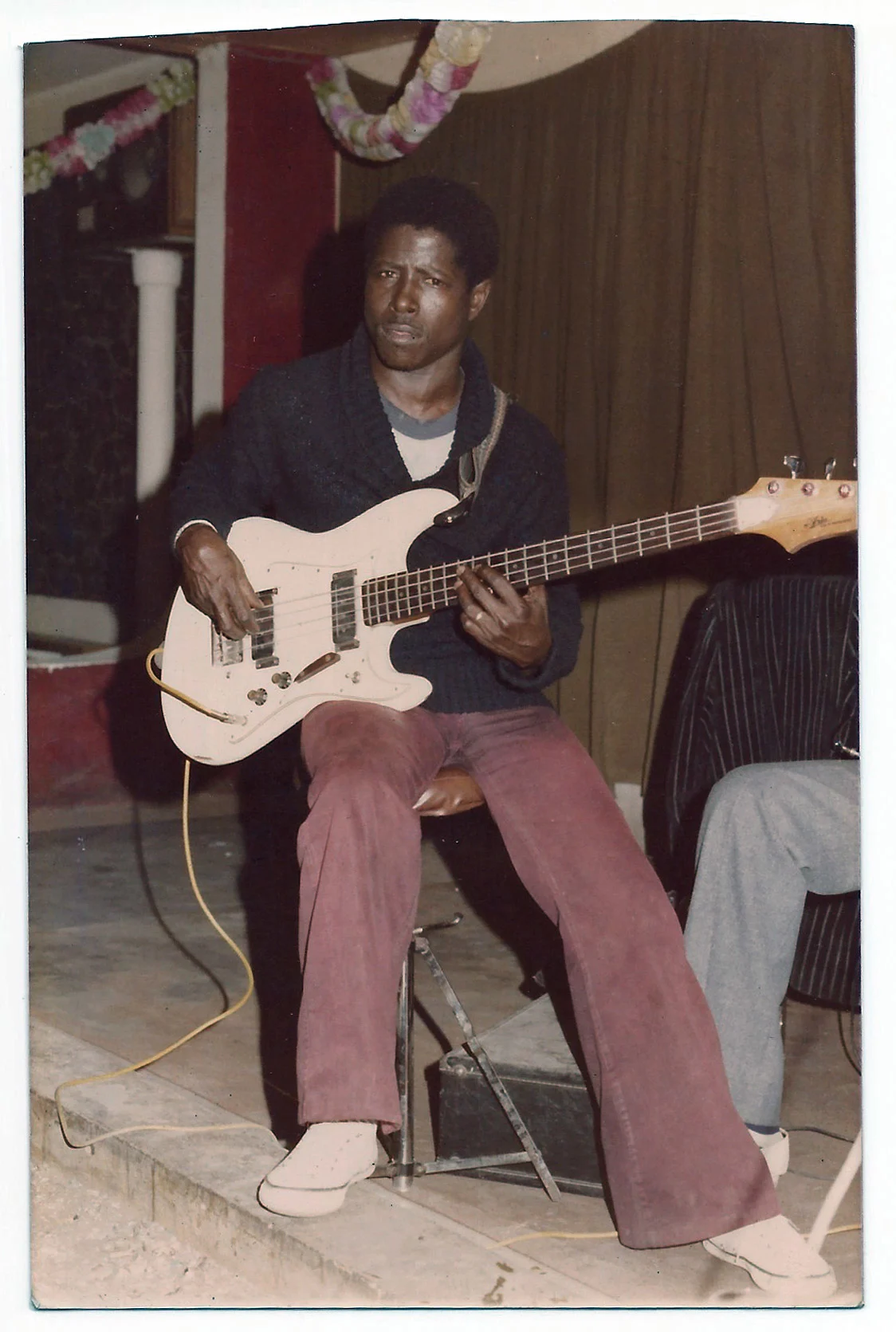

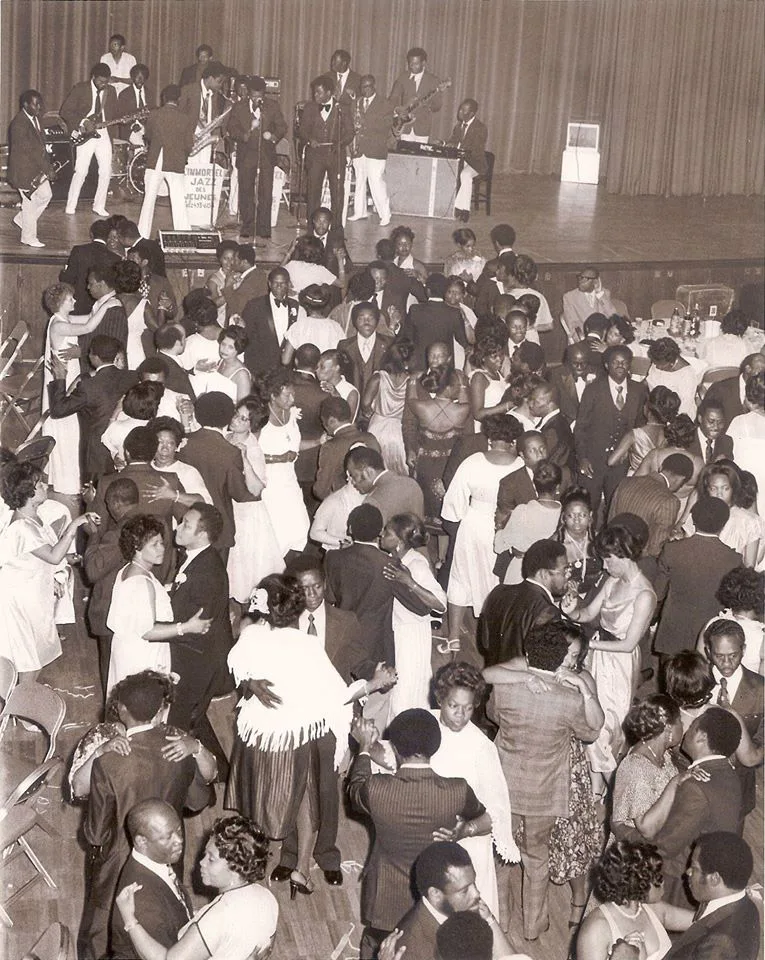

With both their reissued music – and new projects like Groupe RTD’s The Dancing Devils of Djibouti – and their most recent release, Djibouti Archives Vol. 1 Super Somali Sounds from the Gulf of Tadjoura, Janto and Vik understand the impact of essentially rebuilding a cultural legacy lost to time, infrastructural gaps, and political disruption. “So much of the music from the 60s, 70s and 80s were lost. There wasn’t a real industry that was powerful enough to make it over the Atlantic in many of these places,” Janto explains. While working on the 2019 release of Star Band de Dakar: Psicodelia Afro-Cubana de Senegal, Janto remembered growing up hearing music from the band, who made their name performing Afro-Cuban rumba, changüí, guajira, and salsa, mixed with Mbalax guitars, Sabar drums, and sung in both Spanish and Wolof, across nightclubs in the 1970s. Inspired by the limitless possibilities of liberation after the Cuban revolution, its music served as a portal to radical modernity for Senegalese youth and musicians, bound by the history of a then deeply segregated Dakar. “I realized that the younger generations in a lot of African countries, including Senegal, don’t know a lot about that musical history because there’s this very dominant American narrative that took away a lot of the cultural power of the countries themselves. This kind of work is re-establishing a certain knowledge that, in my understanding, is really helpful.”

Much like Vik, Janto sees music from these countries and eras as a product of their environments, textured and layered due to their role as a vehicle for healing, both national and personal. “It’s unpretentiousness,” he says after carefully considering his response. “In places where you have an oppressive system, it was a way to communicate, also. That sparked so much creativity in terms of lyrics, in terms of writing. It’s a weird thing because on one hand, I don’t want that kind of sorrow, that kind of struggle, for anyone. But these things have always created the best music.”