In “I Went on a Holiday to the Country You Fled From,” photographer Iris Haverkamp Begemann and writer and activist Alejandra Ortiz weave together experiences of belonging and rejection to create a portrait of modern global identity, and the paradoxes of freedom. Here, the duo tells Gem Fletcher about survival, self-expression, and how listening to one another can prepare us for a better future.

There is something really powerful about building a friendship; about learning to care and rely on each other. It's about growth, vulnerability and showing up. It's about texting when you get home and answering late-night calls.

We love our friends, and for many of us, especially in the queer community, they become our chosen family. But that doesn't mean it's easy. Solid, intimate, connected friendship is not effortless for anyone—especially when you experience entirely different lived realities.

Writer and activist Alejandra Ortiz and photographer Iris Haverkamp Begemann met through a mutual friend in Amsterdam early last year, and bonded over dating frustrations and their shared love of art. They didn't initially set out to collaborate, but over time, their friendship opened the door to a project exploring the complex ways identity dictates personal freedom. Ortiz identifies as a Mexican trans queer refugee, and has spent the last seven years in a struggle for asylum and safety in the Netherlands, after escaping violence in Mexico. Haverkamp Begemann, a cis straight white woman, grew up in an wealthy family in Dordrecht, a city south of Rotterdam.

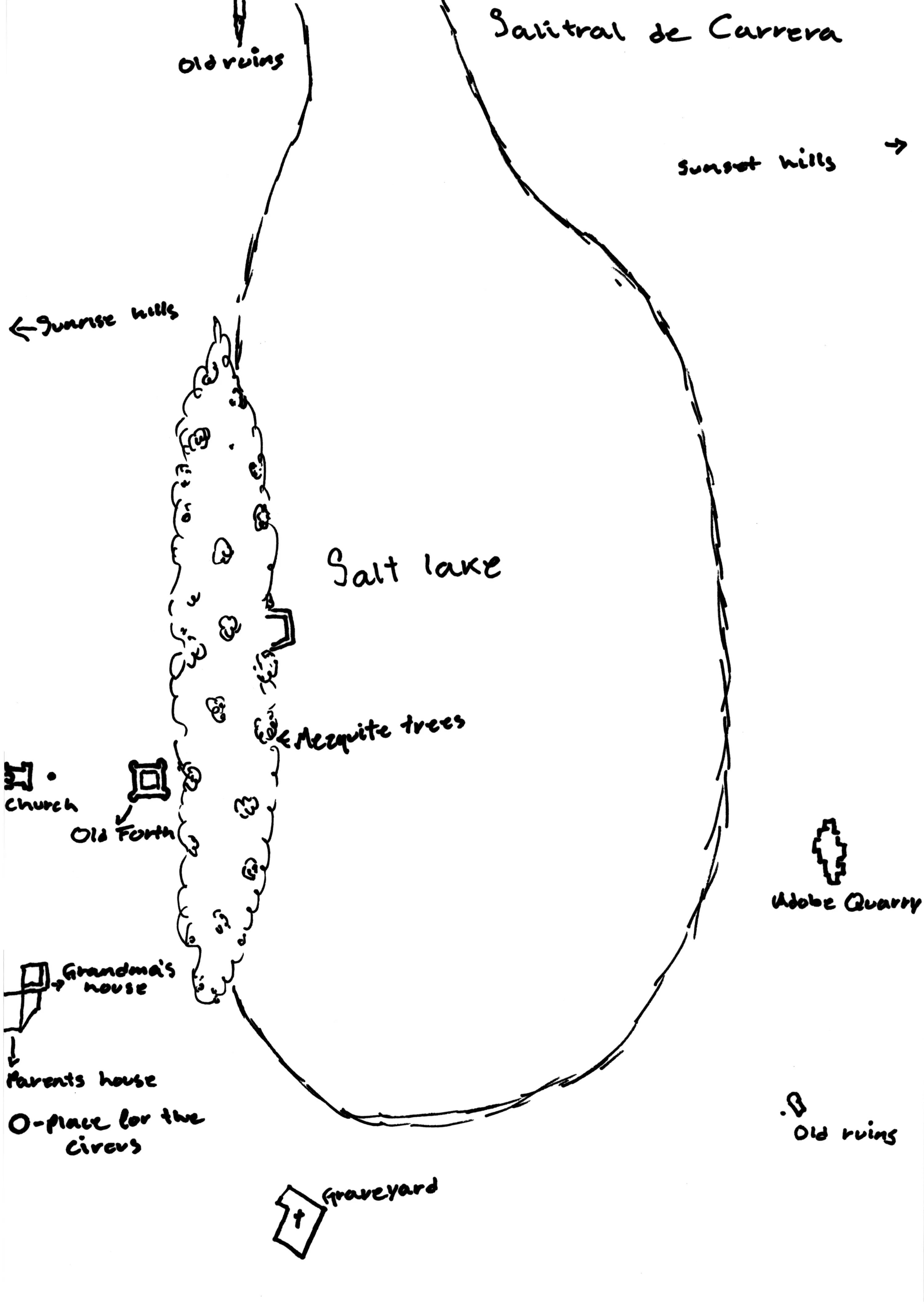

Their collaboration, “I Went on a Holiday to the Country You Fled From,” is a project that straddles two worlds. In November 2021, Haverkamp Begemann spent five days retracing Ortiz’ life in Mexico while on holiday, guided by a hand-drawn map Ortiz created from memory. In an effort to “make use” of her privilege, Haverkamp Begemann photographed Ortiz’s family and documented the places that shaped her life until her departure.

The resulting images are quiet and tender. The streets hum with the sun's warm glow while formal portraits depict moments of repose in everyday life. This perceived ordinariness is dramatically interrupted by Ortiz’s emotional captions. She describes how the people, places and things Haverkamp Begemann photographed are haunted by both conflict and joy. Here, the ephemerality of what seems fixed, like a family, a home and a community, is exposed.

The more active thinking we can do about our privileges, the more we can challenge the system of social injustice.

The lives of trans people are often flattened in our culture, reduced to victim narratives that hide the systemic inequality behind their plight. In this work, the duo insists on honoring depth and nuance as an active mode of resistance.

Ortiz’s story is one of fracture and recomposition. Growing up queer and gender non-conforming in a conservative family in Salitral de Carrera, a town of fewer than 4000, she became accustomed to fighting prejudice. “Since I was little, I knew I was different,” says Ortiz. "But it wasn't coming from me—I was constantly told I was on the wrong side.

Like many LGBTQIA+ people, Ortiz found herself caught in familial conventions geared towards a particular trajectory that didn’t accommodate her transness. Her early life was a battle to survive endless physical and emotional violence until the point that she could escape it.

For many years I tried to comply, stay silent, and not make noise, and I realized I had been holding so much pain, drama and self-hatred.

“I tried to act ‘normal’ and disguise my effeminate nature, but it was impossible with this combination of extreme patriarchy, Catholicism, and machismo culture. My dad was a macho man and wanted me to be macho like him,” Ortiz said. “A defining childhood moment was when I was four, playing dolls with my female cousins in my grandma's house. My uncle started to make fun of me and called my parents. My dad removed my belt and started hitting me. That's when I started to assimilate that whatever I felt was wrong.”

To escape the violence, which persisted well into Ortiz’ teenage years, she found a safe haven in her grandma Elvira's house. “My grandparents adored me,” she explains. “They never judged me, despite their traditional rural background. My parents would drop me off at her house for long periods, and on warm summer nights, we would sit on the porch, and she would tell me stories about her life and the village. When I was 12, I discovered her clothes from the ’70s buried in the back of her closet. I would put on her caftans and dance alone to ‘Saturday Night Fever,’ imagining myself at a fancy party, like the ones I saw on TV movies.”

I’ve realized the more open I am, and the more I share my story, the lighter I feel.

While progress has been made in regards to LGBTQIA+ rights in Mexico over the last five years, the extent of this acceptance varies significantly across the country. Trans people continue to face high levels of discrimination, with many expelled from their homes at a young age and unable to access the job market; and authorities show little inclination to investigate violence against trans people.

Ortiz fled Mexico when she was 19—first to the United States and later to the Netherlands. She quickly discovered that the conventional narrative of moving west to find freedom was much more complicated than she’d been led to believe. “It's challenging to find your place,” explains Ortiz. “There is a cascade of oppression that gets more complex the more intersectional your identity is.” Until her petition for asylum is resolved, Ortiz continues to live in limbo, unable to officially start her life in the Netherlands but unable to return to Mexico.

I tried to act ‘normal’ and disguise my effeminate nature, but it was impossible with this combination of extreme patriarchy, Catholicism, and machismo culture.

“People often ask me how I felt about Iris visiting my hometown, but the truth is it initially didn't have much impact on me,” Ortiz explains. “I've been separated from my family for over 20 years. It only hit me when she brought my village to Amsterdam through her photographs. For many years I tried to comply, stay silent, and not make noise, and I realized I had been holding so much pain, drama and self-hatred. Making this work has been very cathartic. I've realized the more open I am, and the more I share my story, the lighter I feel.”

For Haverkamp Begemann, “I Went on a Holiday to the Country You Fled From” is not just a lens through which to view the nuance of Ortiz’s lived experience, but also an invitation to cis viewers to deconstruct their privilege. “The more active thinking we can do about our privileges, the more we can challenge the system of social injustice. People with my identity are responsible for this systemic oppression, yet they have no empathy for others who have to fight every day just to be seen. This work is about holding a mirror to the institutions and individuals and the paradox of identity they uphold.”

“Just like my dad wears cowboy boots because that’s what a cowboy should wear, I wear my heels because in my mind, I’ve got an idea about what a woman is: A woman wears heels. My father and I, we both are conditioned by strict and binary gender roles.”

“This is the map of my native village—a place I haven't visited for over 10 years—which I drew from my own memory. Marked are the following places: The nameless salt lake, the adobe quarries on the other side of the village, old ruins by the adobe quarry and on the northwest of the lake, and the cemetery on its southwest bank. In the village, the most important places are the “Casa Grande” (an old fort), the church of the holy cross and my grandma’s house right next to my parents' house. Before Iris embarked on her journey to my native village, I handed her the map to take with her, guiding her to the places that meant a lot to me.”

“I’ve walked on these streets many times, but sometimes there was no escaping the bullies and I had to hide. There were a lot of boys during the day, boys around my age and older. They used to chase me and throw stones, they routinely insulted and beat me. One time, this guy put a firecracker on my back and it exploded. Maybe I still have the mark. I don't know. The women or the girls, the older people, they were not as mean, but they would laugh, or make mean remarks about me.”

“I used to sit on this zaguán (a Mexican porch), when I was little, during warm summer nights, with my grandmother. She used to tell me stories about her life and the village. She was the only one who remembered my birthday and didn’t think of me as the devil.” I am sure my grandma knew I was different. When I was around 12, I used to open this closet and found female clothes from the ‘70s. I used to dance alone to the soundtrack of Saturday Night Fever (in her house I found old vinyls with beautiful music). I imagined myself attending a fancy party, dressed in a caftan, just like in the ‘60s movies shown every Sunday on TV. She caught me dancing in those clothes several times, I don't know why, but she never said anything.”

“Several times boys—around my age and older—hung me from a mesquite tree upside down and hit me for like 2 hours. Adults who were passing by found it cute and funny. Back then, I didn't think much of it. It was simply a fact of life. I went to kindergarten when I was five with one of them. But the more I grew up, and the more obvious it was that I was not straight, the further apart and more hateful he and the rest became.”

“Days ago, I called my mom and she said that she loves me. For years I longed to hear those words. But now, I felt so void of feelings, it made me feel dry. What was the point? I'm already on the other side of the world, and there is an ocean between us.”

“One time my dad was crossing the border to go to the U.S. and the coyote (people smuggler) said to him “put some tennis shoes on so you can run.” He went running through the border on cowboy boots. When I visit my dear friend Willemijn in Limburg and we walk up and down the hills, I wear these heeled boots. I didn't want to be like them (my parents). It’s very confronting to become more and more like my dad.”

“So this image confronts me with my dad, who was very vain, very irresponsible, narcissistic, who used to beat my mother and who left us hungry. Both my parents were so vain, they had a toothbrush to brush their teeth. I didn't have my first toothbrush till I was 16. It's no coincidence that when dating, I choose men that are like him. Because that's what I know.”

“The sunlight is beautiful, but it's the shadows that I don’t like in this image. Shadows are sneaky. You cannot catch a shadow. If you catch something, then you get a hold of it. You more or less can play around it. But shadows become so sneaky. This image is a metaphor for the repressive influence machismo and religious culture has had on me.”

“This is the salt lake viewed from the cemetery. Water has always made me feel relaxed. I think it's because I come from the desert, where it rarely rains. Water used to relax me and make me happy. I used to walk in places where there were no people a lot; in those isolated places no one would bother me. I know this landscape by heart. Even during the rainy season, the lake is very shallow, so I would roll my pants up and walk in the water. This image is my favourite. One day, when I have a home myself, I hope I can frame it and hang it on my wall.”