With every vital political movement that couldn’t be silenced, there wasn’t just a need to be heard by the outer world at large. That movement also had to be visible. As a continuation of our collaboration with PAST. and Russell Tovey, we tell the powerful and layered history of AIDS activism through the humble T-shirt. In this exhaustively researched piece, PAST. tell poignant stories about the garments worn by protesters or designed by those within the resistance. Each and every T-shirt—when worn en masse by body after body—was anything but throw-on and throw-away. They said something.

Foreword

Look down at what you’re wearing right now. Might your clothes tell the world anything about you? The ubiquitous nature of T-shirts in particular makes them a powerful tool of activism. And no cause has harnessed that tool to greater effect than the LGBTQ rights movement.

Lesbian and gay activists of the 1970s cleverly transformed the humble T-shirt into a canvas of pride and protest. In the 1980s and 1990s that resourcefulness was enlisted to help fight the war on AIDS. While history often leans on traditional sources—diaries, memoirs, photographs and film—the gaps in the tales beckon us to seek stories in unconventional places. These T-shirts offer a glimpse into untold narratives. They are declarations of pride and tenacity that provide a unique lens through which to understand queer history.

This collection represents a cross-section of AIDS activism, from marches to memorials to “kiss-ins”. These T-shirts echo the voices of a movement that refused to be silenced. They are first-hand artifacts. They were present and they each have a compelling story to tell.

CHAPTER ONE: SILENCE = DEATH

The pink triangle was chosen for its reputation as a recognisable and inclusive gay symbol.

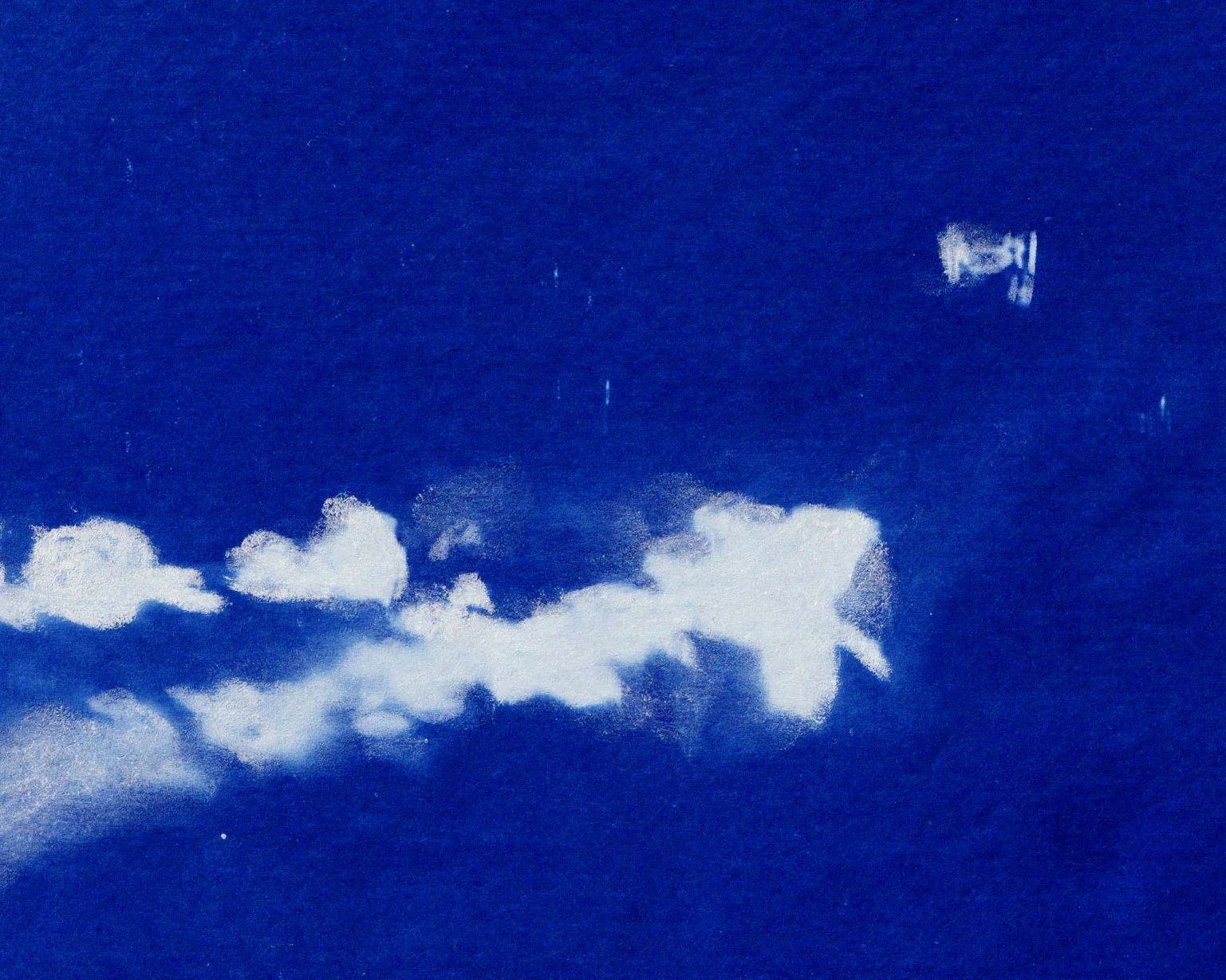

SILENCE = DEATH began life as a head-turning poster on the streets of New York. It was a potent piece of activism; a clarion call for the war against AIDS. In the mid-80s, Brooklyn artist Avram Finkelstein started a consciousness-raising collective. Their goal: to explore what it meant to be gay amidst the AIDS crisis.

Over the coming weeks Finkelstein, along with Chris Lione, Jorge Soccarás, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff and Brian Howard, bonded over their grief and rage. Through their weekly meetings the group discovered the innately political nature of their experience. It was clear to them that the enemy wasn’t AIDS, it was the government, its institutions, and the media. With their anger politicized, the collective began work on a poster that would convey their message: ignoring AIDS is neglectful and has deadly consequences.

They knew the potential power of a poster. In an age before the internet, the most effective means of disseminating information outside of mainstream media was the streets. But this was the 80s and there was no time for long winded manifestos. To grab attention their poster had to be brief, vernacular, catchy and cool.

The pink triangle was chosen for its reputation as a recognisable and inclusive gay symbol. Traditionally pale pink, the triangle was updated with vivid fuchsia and turned upside down. In fact the reversal was an accident that was later imbued with meaning: inverting a symbol of victimhood to reclaim power.

The group devised a simple and irrefutable statement, SILENCE = DEATH. Finklestein dubbed it, “New Math for the Age of AIDS”. The vast black background gave the graphic room to resonate. With wall space at a premium in New York City, the expansive background was defiant and formidable in its refusal to fill space with economy. In March 1987, SILENCE = DEATH was wheat pasted across Manhattan.

CHAPTER TWO: ACT UP

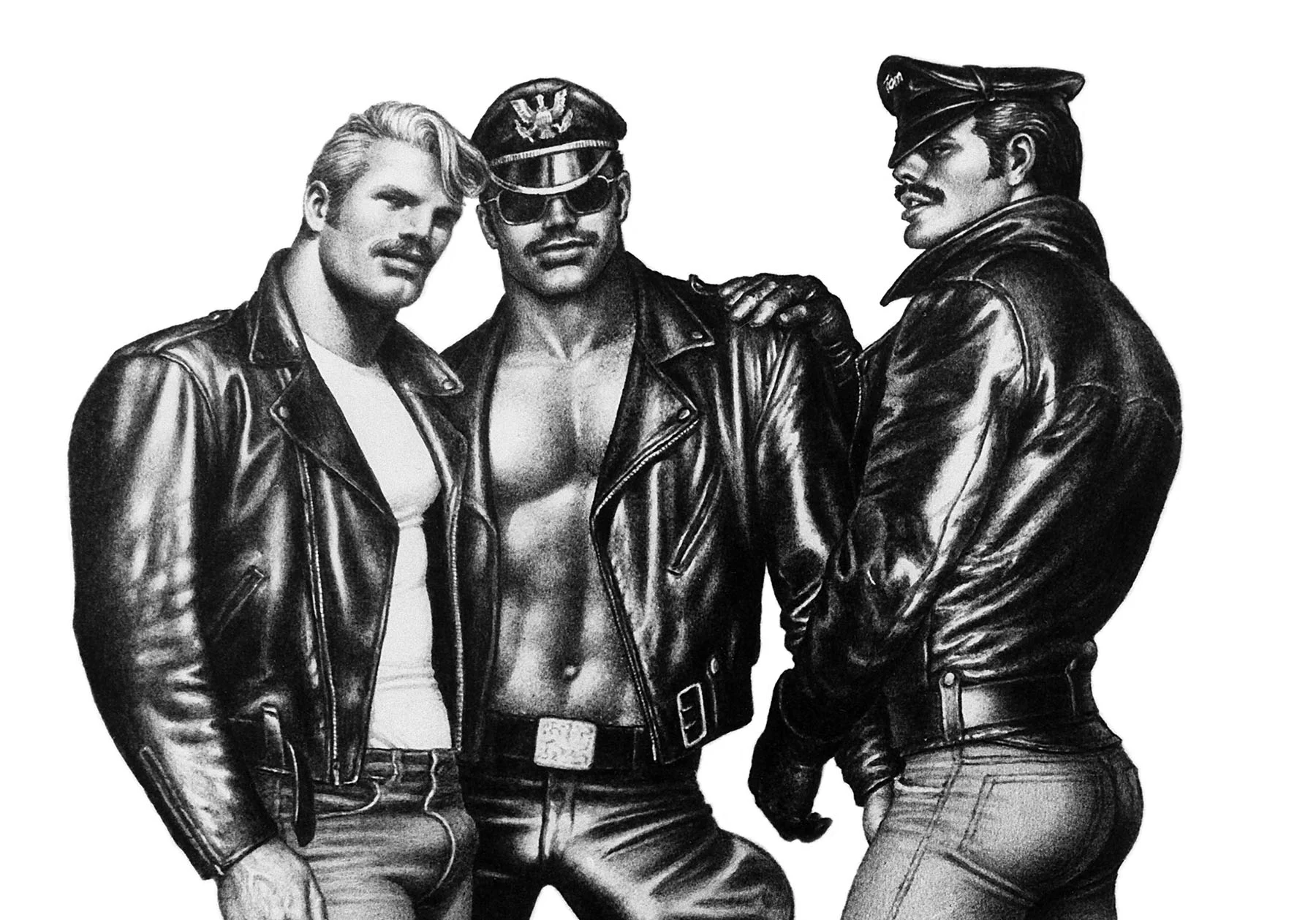

Mainstream America was already squeamish about queer imagery, let alone with the added context of AIDS.

As SILENCE = DEATH was being wheat pasted across Manhattan, another alarm was being raised. At the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York, Larry Kramer gave an impassioned speech, declaring to one half of the room, “You’ll all be dead in a year…what are you going to do about it?”

His appeal prompted the birth of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which would adopt the SILENCE = DEATH graphic, rolling out T-shirts to be worn at demonstrations. It was a savvy move. The T-shirts continued the consciousness-raising intentions of the original poster while infiltrating places a poster or a placard couldn’t. SILENCE = DEATH was so successful it became synonymous with ACT UP, occupying the frontlines of their demonstrations for years to come. But ACT UP had its own diverse pool of experienced political advocates, artists and designers, from which a brand of aesthetically compelling activism emerged. ACT UP’s famous guerrilla graphics were designed by their own in-house propaganda machine, Gran Fury. Fuelled by rage, the group’s provocative graphics pulled no punches.

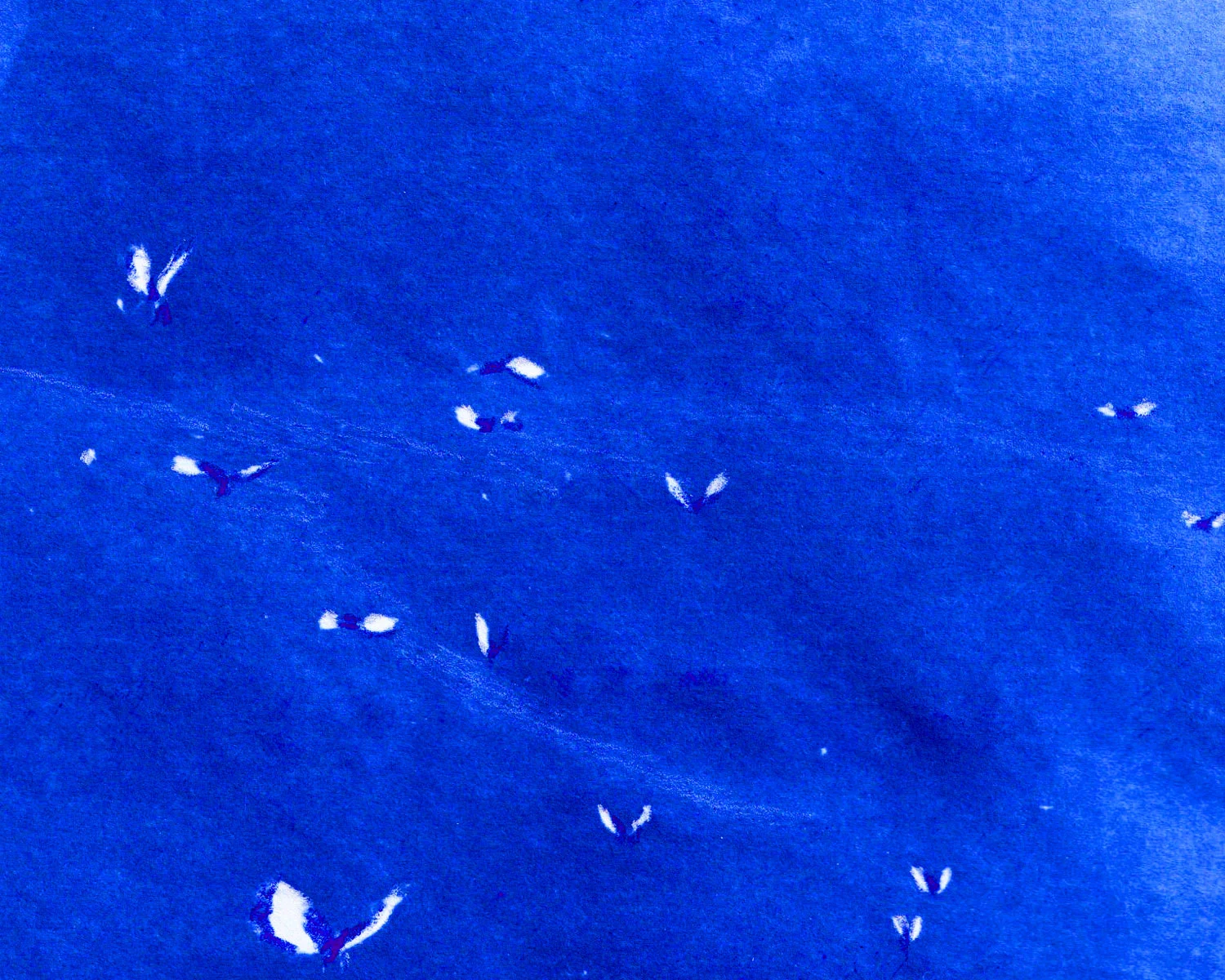

Gran Fury’s controversial “Read My Lips” campaign spoke to the confrontational nature of expressing queer sexuality in public. Mainstream America was already squeamish about queer imagery, let alone with the added context of AIDS. The photograph of two sailors kissing in an intimate embrace was an audacious move.

The ad was the brainchild of Gran Fury member Tom Kalin. With Kalin’s history of employing kissing imagery in his work and with the recent launch of George H.W. Bush’s election campaign catchphrase “read my lips, no new taxes”, the ad designed itself. “Read My Lips” challenged the Bush campaign, which signified a continuation of Reagan’s inadequate AIDS policies. The decision to steal the aesthetic of conceptual artist Barbara Kruger was deliberate and precise. Evoking the styles of political artists who were yet to tackle the subject of AIDS in their work became one of Gran Fury’s trademarks.

But not all ACT UP graphics required the prowess of Gran Fury to make an impact. Another demonstration T-shirt represents ACT UP’s 1990 Albany Action. The front shows a photograph of an ACT UP IS WATCHING sign from a previous protest. It serves as a reminder that ACT UP was committed to holding leaders accountable.

The Albany Action took place on March 28 1990. ACT UP members flocked to the New York state capitol of Albany to protest Governor Cuomo’s AIDS budget. A year earlier Cuomo admitted the budget had been hamstrung by looming tax cuts and would not deliver the essential services needed for patients across the state. He pleaded with activists to refrain from protesting, promising to find the money from somewhere. “Remind us in a year,” Cuomo said. Demonstrators converged on the governor’s mansion in Albany, chanting “you said come back in a year!” and “no more status Cuomo.”

They then moved to the Capitol Building in an attempt to shut down the capitol. Some staged die-ins in the hallways. A small group commandeered the balcony and rolled out a sign that read “Deaths of People With AIDS Are a Capitol Crime”. Red handprints were left on the stairs and banisters and red tape was draped around the building. By that evening 83 people had been arrested.

Bruce Monroe: G.U.T.S

G.U.T.S. narrated by Bruce Monroe

CHAPTER THREE: KEITH HARING

An activist at heart, Keith Haring believed in the power of art to shape public perceptions.

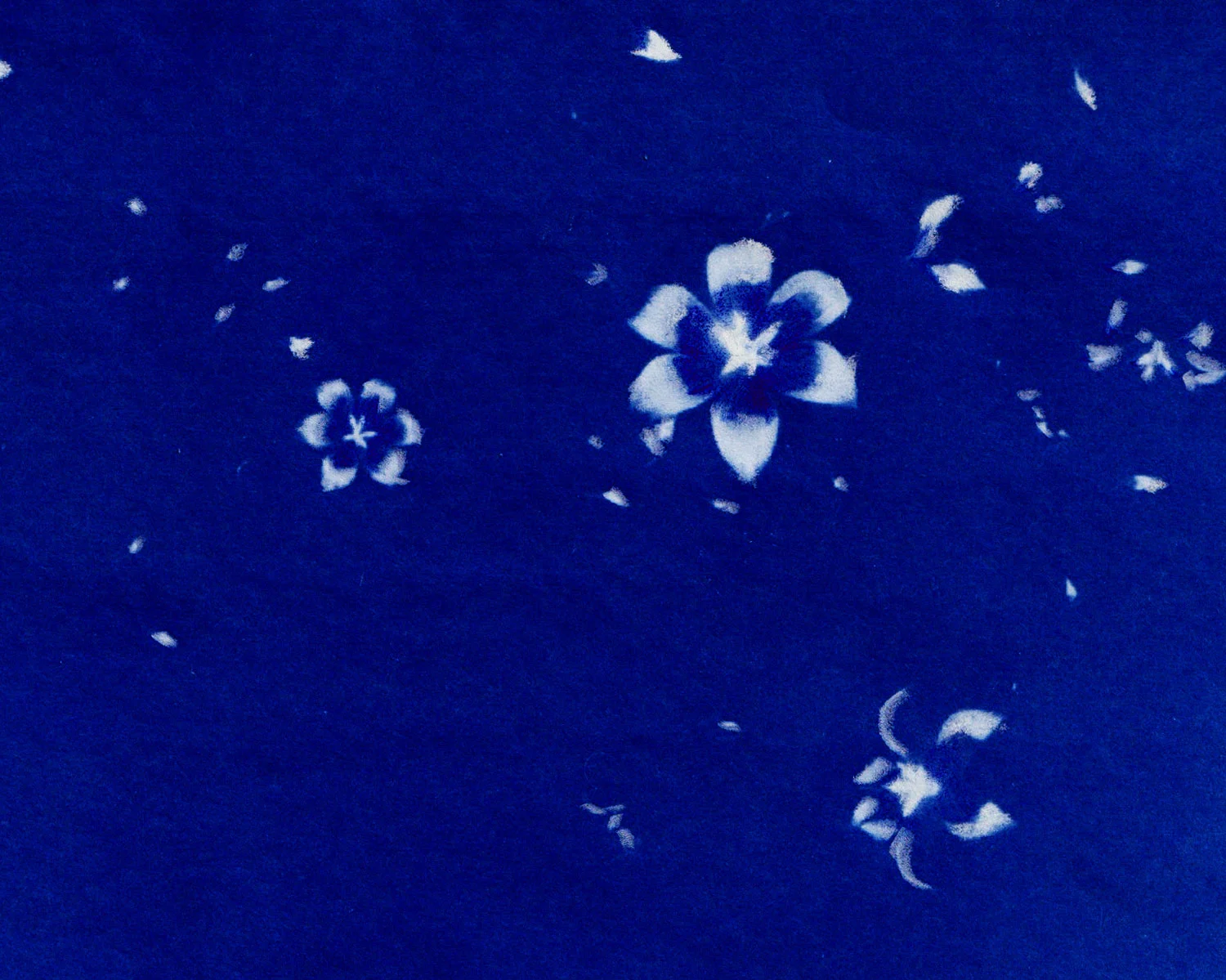

An activist at heart, Keith Haring believed in the power of art to shape public perceptions. He advocated for change in a way that transcended cultural boundaries. Haring got his start as a graffiti artist, where he developed his unique artistic language: playful tableaus embedded with a sociopolitical message. With the New York Subway as his backdrop, Haring reached a diverse audience, many of whom would never have considered attending an art gallery. His tenet: art is for everybody. Haring opened the Pop Shop in 1986 in New York’s Soho, prompting criticism from the art world for selling out.

By the end of the 1980’s Haring was the undisputed king of activist art, but his desire to keep his work accessible never wavered. “STOP AIDS” (1989), which depicts a pair of human scissors cutting a red serpent is a prime example. It provides a powerful metaphor for the belief that the community would have to work together in order to end AIDS. This T-shirt is an original piece of Pop Shop merchandise from between 1989 to 1992. By 1986 his subway drawings were being ripped down and sold at a premium; the Pop Shop marked a new way of bringing art to the people. With proceeds going to The Keith Haring Foundation, Pop Shop consumers could contribute directly to his mission. Haring’s static street art was now on the move as his T-shirts flew off the shelves and onto the backs of activists and art fans alike.

Two years later Haring was diagnosed with AIDS, prompting him to concentrate on AIDS messaging in his final years. As a member of ACT UP he participated in their demonstrations and lent his visual brand to their cause.

This T-shirt is a monochrome version of a full-color poster that Haring designed for ACT UP in 1989. Ten-thousand posters were printed as part of a wheat pasting campaign, turning the heads of drivers, subway passengers and pedestrians across New York. “IGNORANCE = FEAR / SILENCE = DEATH” married two powerful ACT UP slogans with his own visual symbolism. The three figures in a “wise monkey” pose reflect the struggles of the AIDS community and the institutional oppression and neglect they suffered.

In 1990, Keith Haring died of AIDS-related complications. Three decades after his death, his message still resonates: the power to change the world is within your grasp.

CHAPTER FOUR: THE NATIONAL MARCHES ON WASHINGTON AND AIDS MEMORIAL QUILT

“For love and for life, we are not going back!” - Rallying cry from the 1987 March on Washington

National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1979

The 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights made history as the first event to bring lesbian and gay issues to the national stage. To march or not to march had been the subject of debate for years, with some believing the timing wasn’t right. But the assassination of Harvey Milk in 1978 emboldened the community to act. It was agreed the march should take place the following year, to coincide with the tenth anniversary of Stonewall. With the rallying cry, “we are everywhere!” tens of thousands of people sent a powerful message: the rights and dignity of gays and lesbians are non-negotiable.

America was unwittingly on the cusp of the AIDS crisis; it was a timely moment for the lesbian and gay community to unify at a national level. The 1979 march would become the foundation upon which AIDS activism of the 1980s would build, sowing the seeds for networks and activist groups across the country.

The T-shirt for this march says “I’ll Be There!”. T-shirts like this may have provided advertising in the lead up to the event and were worn to the march itself as a statement of solidarity and pride.

Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, 1987

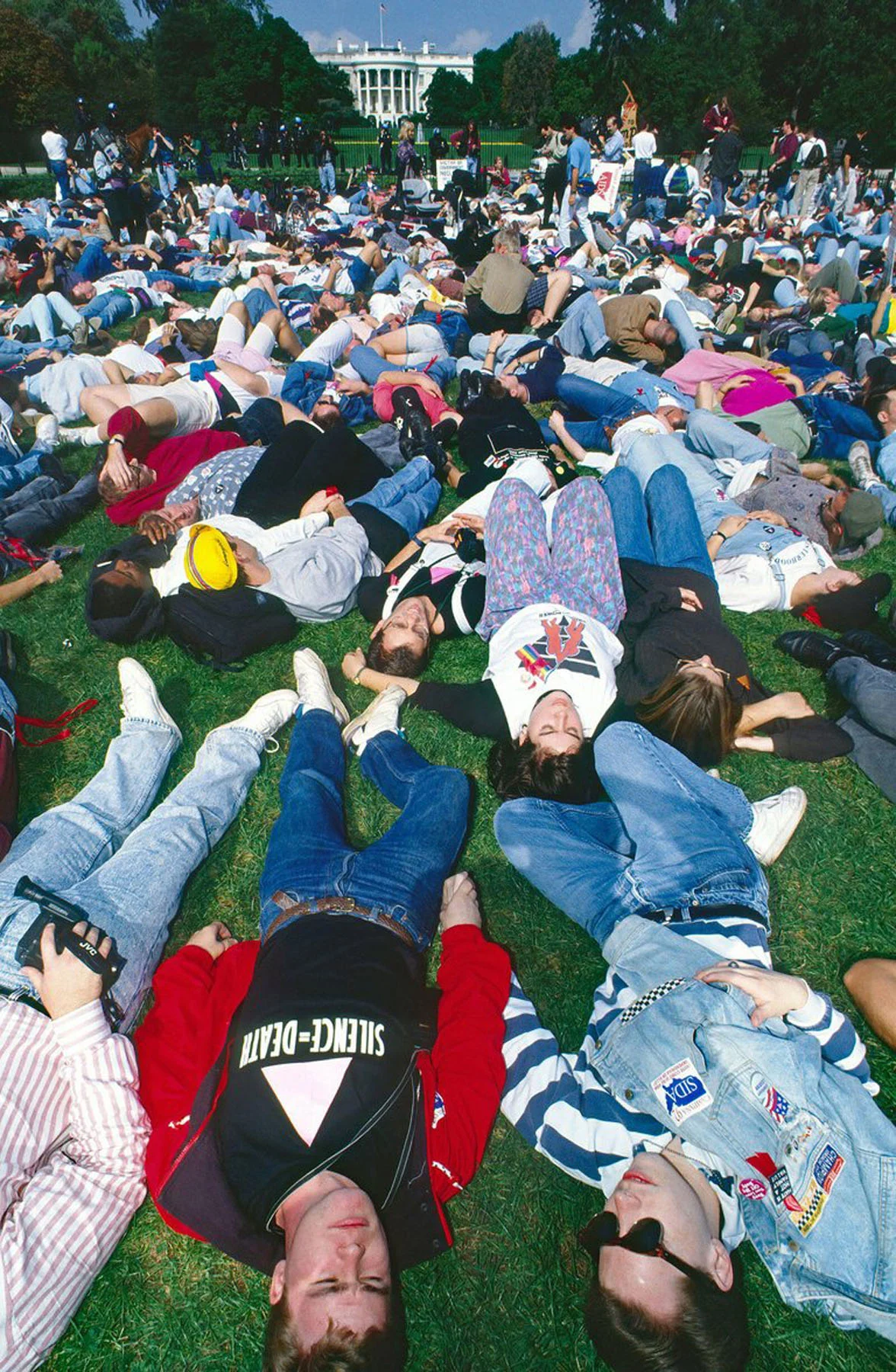

In 1987, demand for political change was greater than ever as AIDS deaths escalated. This time there would be no debate: it was time for a second march on Washington. The march was held on October 11 and approximately 750,000 attended, making it the biggest gay rights march to date. With the slogan, “For love and for life, we’re not going back!”, the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights would take a more urgent and impassioned tone.

It was prompted partly by the government’s indifference to AIDS, and partly by the recent Bowers vs Hardwick ruling, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy laws and criminalised consensual homosexual activity.

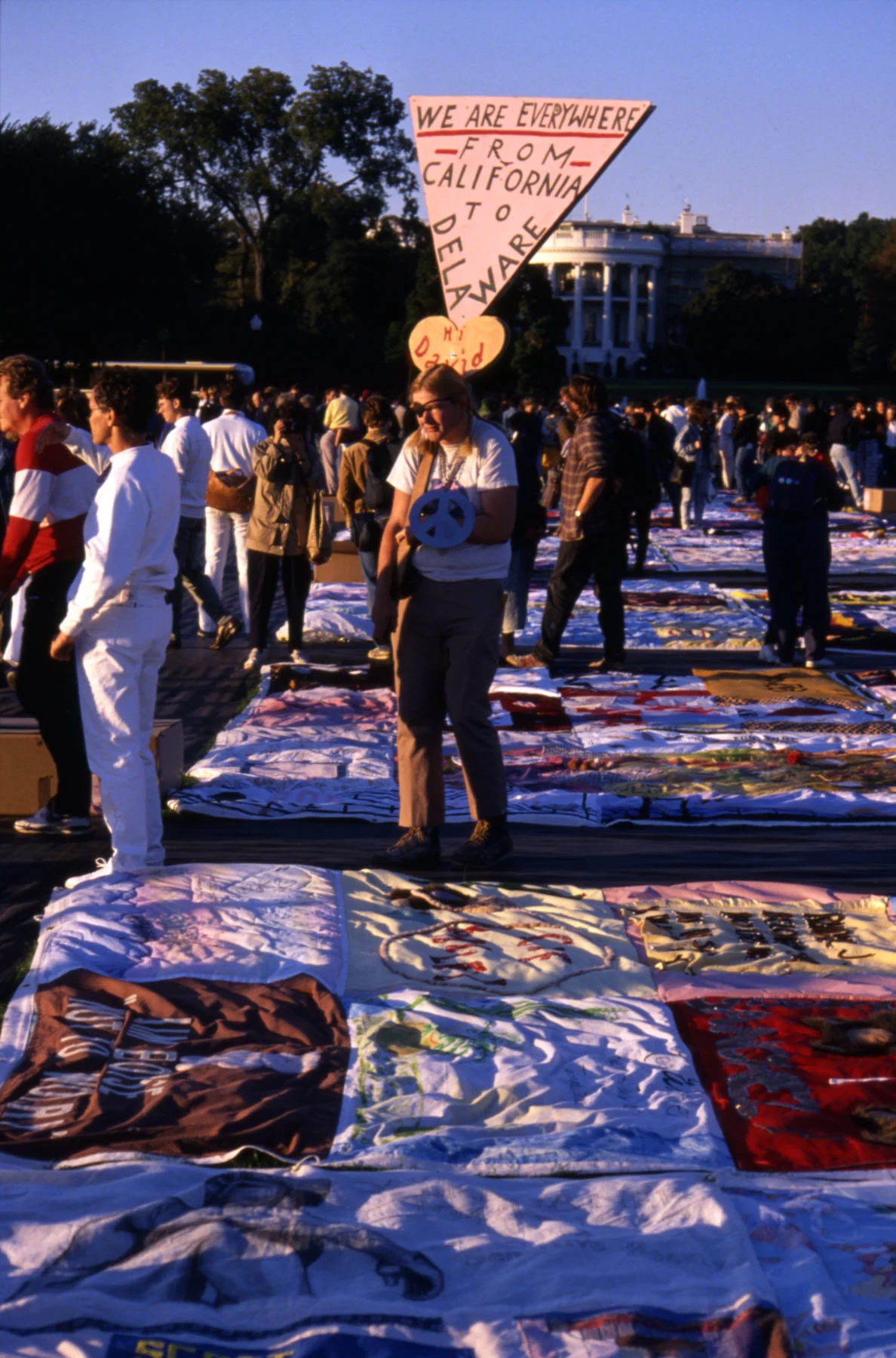

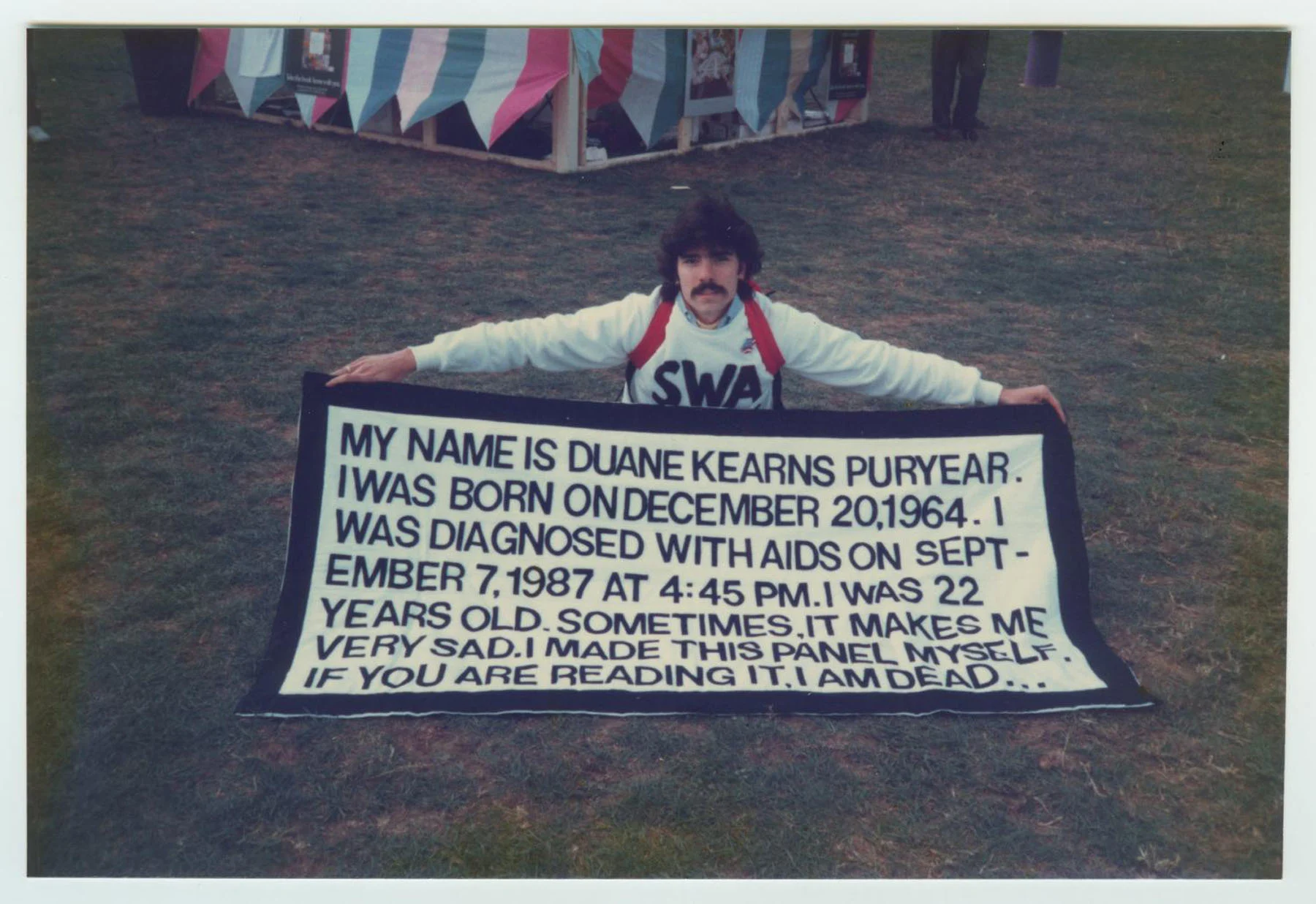

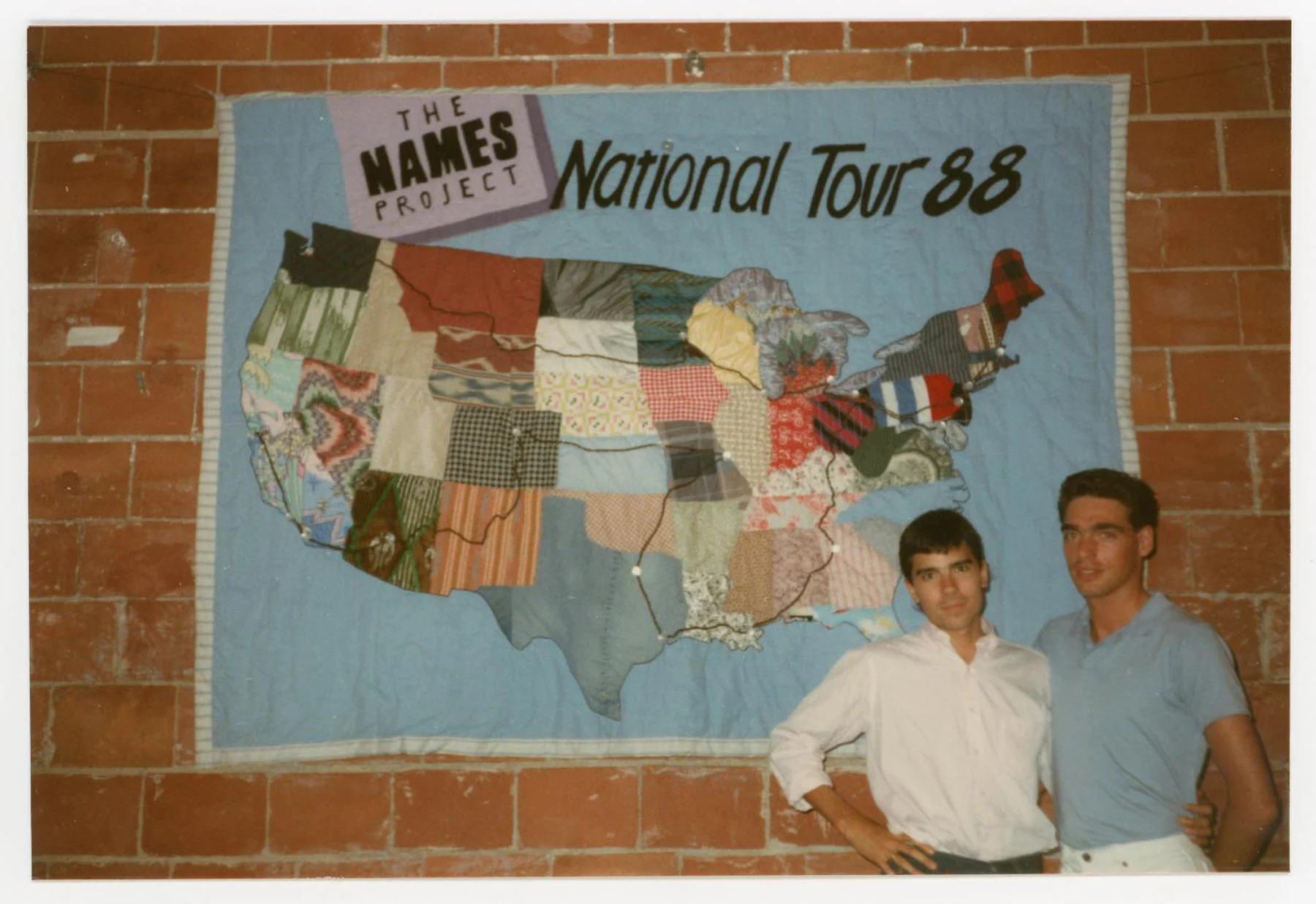

The programme of events was scaled up from the last march. ACT UP staged a demonstration at the Supreme Court Building and “The Wedding”, an act of civil disobedience, saw hundreds of same sex couples take part in a mass marriage ceremony. It was also here that Cleve Jones’ NAMES Project Foundation unveiled the AIDS Memorial Quilt for the first time.

On this T-shirt, a rainbow of stars are flying from California to Washington, represented by the Capitol Dome encased in a pink triangle. It evokes the now nationalized nature of the community, offering a snapshot of how the lesbian and gay rights movement had progressed in the face of AIDS.

Gert McMullin: The AIDS Memorial Quilt

Gert McMullin tells the story of The AIDS Memorial Quilt, which was first unveiled at the 1987 National March on Washington.

National March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi-Equal Rights and Liberation, 1993

On April 25 1993, the National March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi-Equal Rights and Liberation would eclipse the 1979 and 1987 marches. Advancements in activism since the first March on Washington had shifted the queer community towards greater alliances with the civil rights and feminist movements. Consequently close to a million people attended. It would be one of the biggest national marches in US history.

The march was motivated by continuing challenges that persisted into the early 1990s. Discriminatory policies rolled over and the US government continued to stall on AIDS. And with President Bill Clinton’s in-coming “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy, the time was ripe for the community to make their voices heard again.

During his campaign for president, Bill Clinton had promised to abolish laws that excluded non-heterosexual people from military service. “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” allowed non-heterosexual citizens to serve in the US military provided they did not disclose their sexuality. To many in the LGBTQ community, the policy represented a betrayal of Clinton’s campaign pledge. He sent a letter of support to the march that would be read aloud by Nancy Pelosi (then a representative from California). She was met with jeers from the crowd.

The march’s official T-shirt continues to picture the Capitol Dome, this time framed by a purple triangle. The corners of the triangle are covered in unique patches that suggest the three named identities: lesbians, gays and bisexuals.

CHAPTER FIVE: NEVER GOING UNDERGROUND

Despite the record-breaking turnout, Section 28 was passed in May 1988. It would be 15 years before it would be fully repealed.

In 1986, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher expressed her concern that children “are being taught that they have the inalienable right to be gay…all of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life. Yes: cheated!” Her damaging rhetoric fanned the flames of the already-rising homophobia in Britain.

In that same year the book “Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin” was found in a school library in London. The depiction of a young girl being raised by two fathers sparked controversy within Thatcher’s conservative government. Such “homosexual propaganda” in schools was thought to be indoctrinating children into a risky lifestyle and undermined traditional concepts of marriage and family.

Such “homosexual propaganda” in schools was thought to be indoctrinating children into a risky lifestyle.

The subsequent media frenzy paired with public outrage compelled the Tory party to table Section 28. The bill banned the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities and schools, threatening to reverse recent improvements for the LGBTQ community. It stated: “a local authority shall not intentionally promote homosexuality, or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality, or promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.

With a parliamentary vote looming in May of 1988, protests mounted. First in London, then in Manchester. On February 20 1988, “Never Going Underground” became one of Britain’s biggest ever LGBTQ rights gatherings with 20,000 in attendance. Their demand: scrap Section 28 . Organizers of the march, the North West Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Equality (NWCLGE), created a simple but effective logo. The words “Never Going” were added to the London Underground symbol. The surrounding text read “lesbians and gay men out and proud”.

Despite the record-breaking turnout, Section 28 was passed in May 1988. It would be 15 years before it would be fully repealed.

CHAPTER SIX: DANCERS RESPONDING TO AIDS

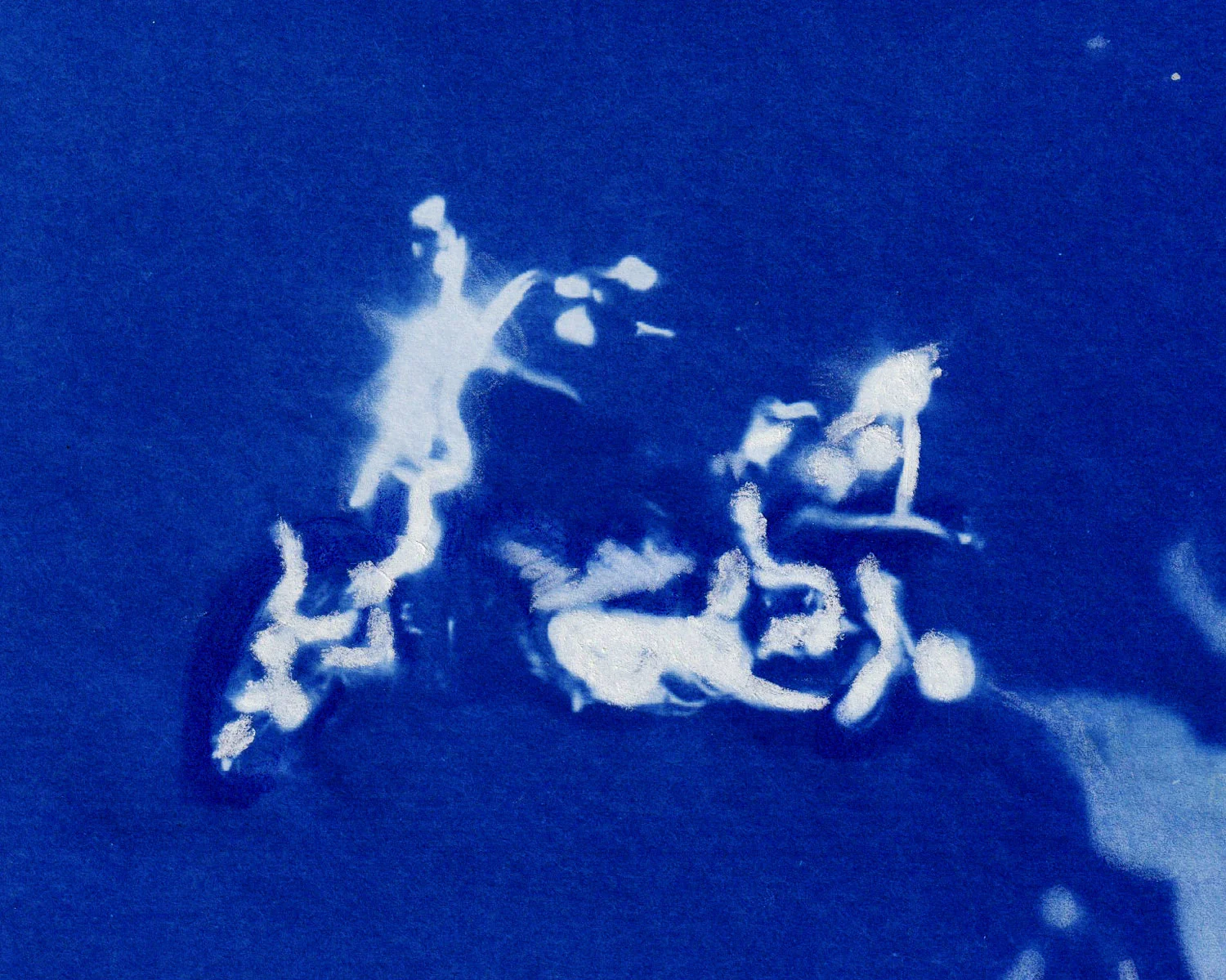

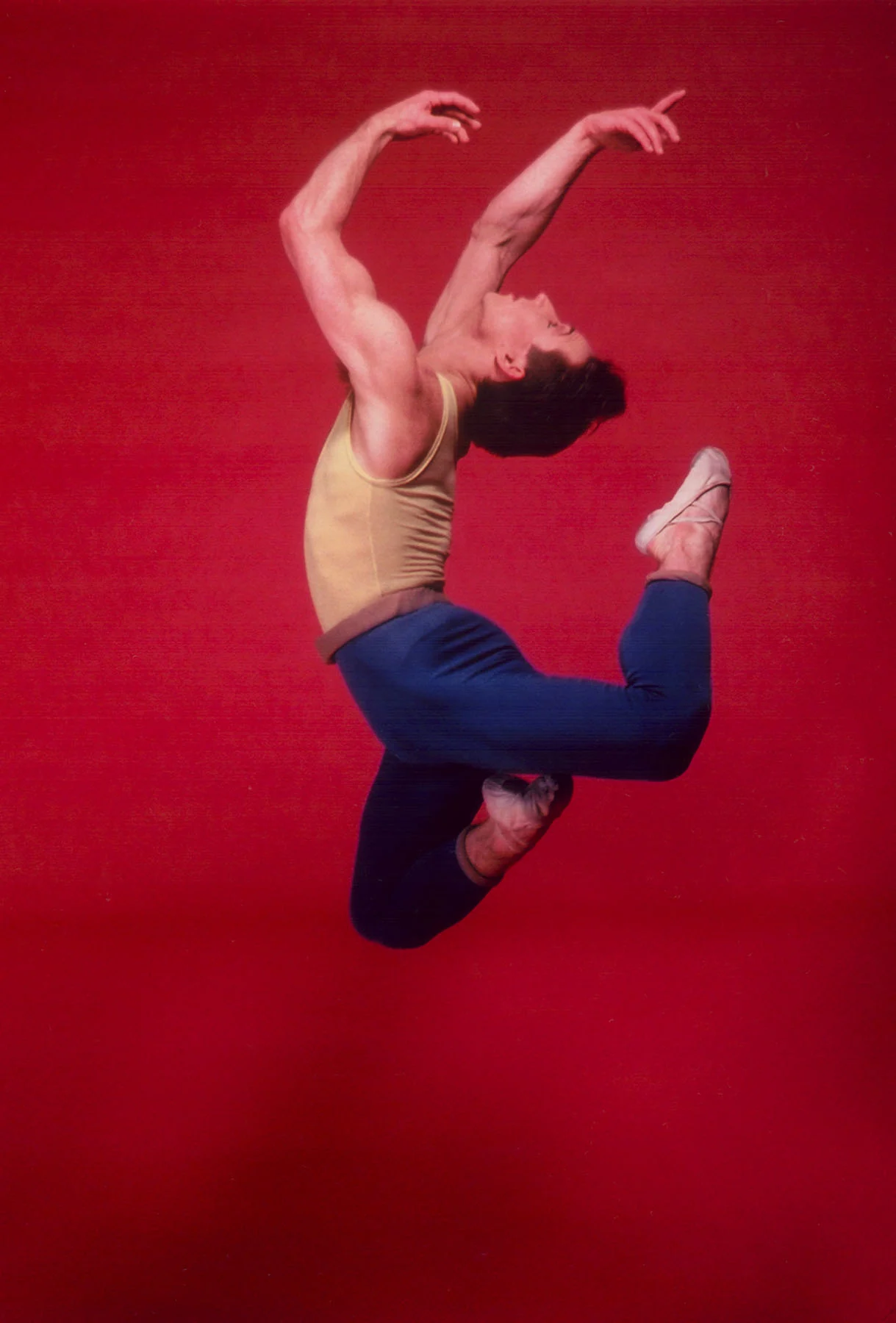

In 1986, Edward Stierle’s star was on the rise. At 18, after winning a gold medal at the International Ballet Competition, he was hand picked to join the prestigious Joffrey Ballet in New York. With his trademark bravado and unbridled ambition, the young juggernaut was cast in central roles from the minute he arrived.

At 19, before his debut as the lead in Gerald Aprino’s “The Clowns”, he was told he’d tested positive for HIV. The diagnosis spurred Eddie (as he was affectionately known) to double down on his work, dancing over 20 leading roles and choreographing four full length ballets. As Eddie’s physical prowess diminished, his determination grew. He choreographed his final piece, “Empyrean Dances”, from his hospital bed.

Meanwhile, across Manhattan, a group of dancers were devising a way to support their friends with AIDS. Denise Roberts Hurlin and Hernando Cortez, members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company, were witnessing the devastating effect AIDS was having on their community. With no existing support for HIV positive dancers, Hurlin and Cortez took matters into their own hands, forming the D.R.E.A.M team (Dancers Responding Eagerly to the AIDS Mission).

Dancers Responding to AIDS: Edward Stierle

Edward Stierle narrated by Russell Tovey

At the 1993 New York Pride march, an army of dancers leaped down Fifth Avenue in a string of all out temps levés. They left their leotards at work—today they were bare chested or wearing T-shirts representing their respective dance companies. Their panache caught the eye of Tom Viola, director of Equity Fights AIDS, who approached the group and struck up a partnership. The D.R.E.A.M. team became Dancers Responding to AIDS (DRA) and has since become an integral part of Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS.

Eddie Stierle would never see the success of DRA. He died in 1991, three days after a standing ovation at the Lincoln Center premier of “Empyrean Dances”. This T-shirt was part of DRA’s early fundraising efforts. Three T-shirts were printed featuring stars of the dance world: Eddie Stierle, Christopher Gillis (Paul Taylor Dance Company) and Clark Tippet (American Ballet Theatre). Each represented the many dancers taken prematurely by AIDS.

Hurlin continues her work with DRA. Their fundraising program includes the prestigious Fire Island Dance Festival. In the last three decades they have raised a total of $300 million to provide financial assistance and support for dancers with HIV/AIDS and other critical illnesses.

This collection was sourced from eBay and kindly loaned by the Internationaal Homo/Lesbisch Informatiecentrum en Archief (IHLIA) and the University of Northern Texas Special Collections. These T-shirts have been reunited with their stories.

See them on display for yourself at “Say It With Your Chest: T-shirts of Queer Protest and Rebellion,” an exhibition running between November 22 and November 25 2023 at 133 Bethnal Green in London.

Project Credits

Executive and creative producers for PAST.

Hugh Coles

Gemma Nicole Atkinson

Rosanna Hyland

Video editor for PAST.

Hugh Coles

Photographer of T-shirts

Sonam Tobgyal, directed by PAST.

Assisted by Jack Dicks

Say It With Your Chest curated by PAST.

Research conducted by PAST.

In memory of Bruce Monroe, Ed Stierle, and all those who courageously fought against AIDS.

With special thanks to archives and contributors:

University of North Texas: Morgan Davis Gieringer, Head of Special Collections, and Justin Lemons

Rose Marie Worton

Denise Roberts Hurlin (Dancers Responding to AIDS)

Gert McMullin ‘Mother of the AIDS Quilt’

GLBT Historical Society, Charles Cyberski Videotapes, number 1994-03

IHLIA LGBTI Heritage: Wilfred van Buuren, Head of Collections, and Gerrit WeBel

Media Burn Archives

Nick Langsley, Never Going Underground Archival Footage

Peter J Walsh

Robert Emery

Smithsonian Institution Archives

The Dallas Way

Tony Arena, Act Up!