Growing up in the Burmese city of Yangon, painter Richie Nath often felt like an outsider. As a half Indian, he was conscious of looking different to his peers, and being gay in a very conservative society didn’t help. Now his paintings, inspired by the bedtime stories and legends of his childhood, are a reclamation of the things he struggled with back then, as the queer characters fight, flirt and pose their way through the mythical worlds around them. Here, Alix-Rose Cowie explores how the unmistakable sense of freedom and strength his portfolio emanates is also a bold, pro-democracy stand against the violence and persecution his friends and family have been facing since the military coup in Myanmar this year.

Warning: This article contains some nudity.

In one of Burmese artist Richie Nath’s paintings, a goddess warrior with a golden spear, blue eyeshadow and flowing black locks defeats a green ogre in a military uniform who falls backward to the ground. Inspired by renaissance depictions of the Archangel Michael, and by the story of Hindu goddess Durga defeating the demon Mahishasura, it symbolizes victory over evil. The title of the piece is Bitch better have my democracy.

Richie published the powerful image to his social media in February 2021, when the military in Myanmar seized power through a coup in the wake of the country’s 2020 general election, and established a state of emergency. In the months since, hundreds of pro-democracy demonstrators have been killed by the ruling military and thousands have been assaulted and detained, according to the monitoring group AAPP (Burma).

Richie is seeking asylum in Paris where he’s currently doing an artist residency for six months. “I can’t go back because I would be arrested and tortured,” he says. His brother is currently in prison and his mother has been arrested and released. He talks to his mum every day. “The political situation there isn’t getting any better.”

Growing up in Yangon – the largest city in Myanmar – under a dictatorship, Richie always dreamt of leaving. He attended boarding school in England as a teenager and went on to study fashion illustration at London College of Fashion. His memories of his home country were of a tight, controlling place. He dreaded returning after university but once he was back in his birthplace, he fell in love with it and found a nurturing creative scene.

“Right before this military coup happened, I could see things were getting better,” he says. “There were so many more people in the creative fields, subcultures growing, new fashions, more people interested in art.” This was new to him; the general attitude to fine art growing up was that it would leave you penniless. He’d been encouraged instead to get a degree in law, finance or medicine first. In the end, he chose to pursue fashion illustration because it promised more commercial opportunity than fine art.

From a very young age, seeing these beautiful sculptural male bodies, I was just incredibly drawn to that.

Although he loved to draw, Richie’s exposure to art was limited growing up; it was mostly what he calls “tourist art:” impressionist depictions of the Shwedagon Pagoda, or paintings of traditional Buddhist monks against a sunset. Once, he came across a picture of The Birth of Venus by Botticelli and he copied the drawing over and over. He was also totally captivated by Egyptian gods. As a child he imagined that when he died he’d go to Egyptian heaven and meet Isis and Osiris, and finding out they weren’t real was his version of being told Santa doesn’t exist.

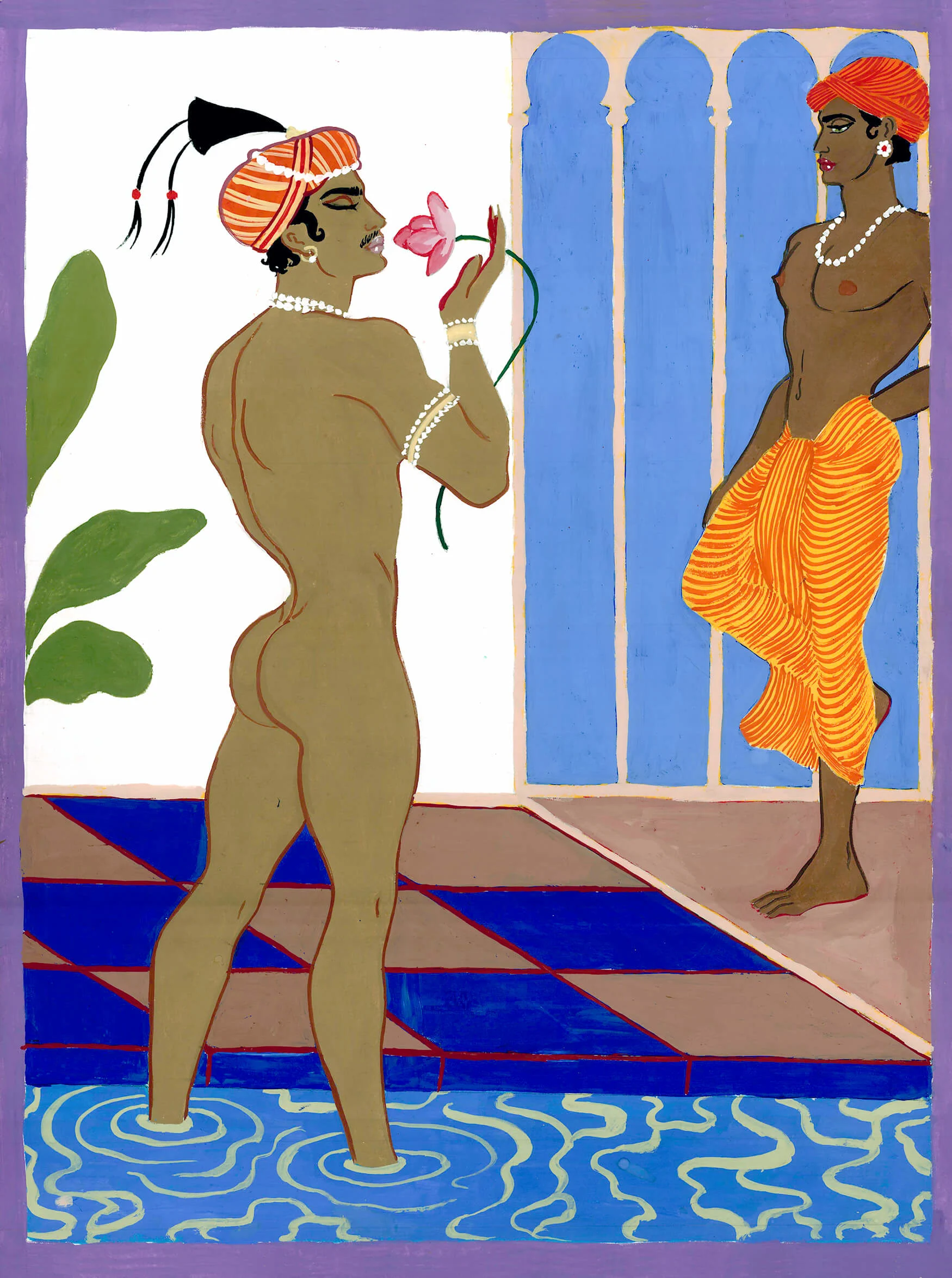

“It was like being hit on the head with a massive pan,” he says, laughing. Greek mythology also left a big impression on him and was the first place he encountered male nudes in art. “From a very young age, not understanding that I was attracted to men but then seeing these beautiful sculptural male bodies, I was just incredibly drawn to that,” he says.

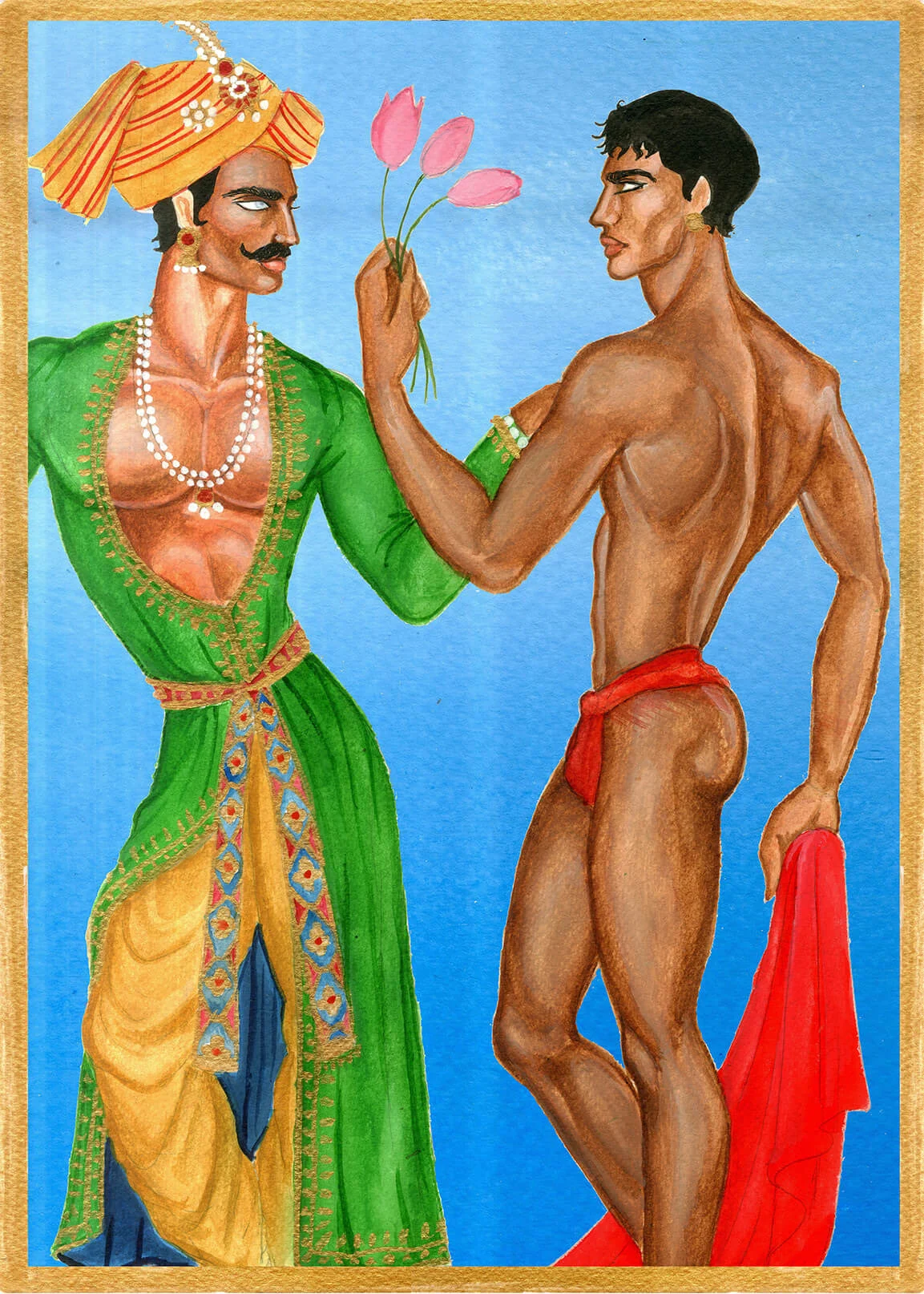

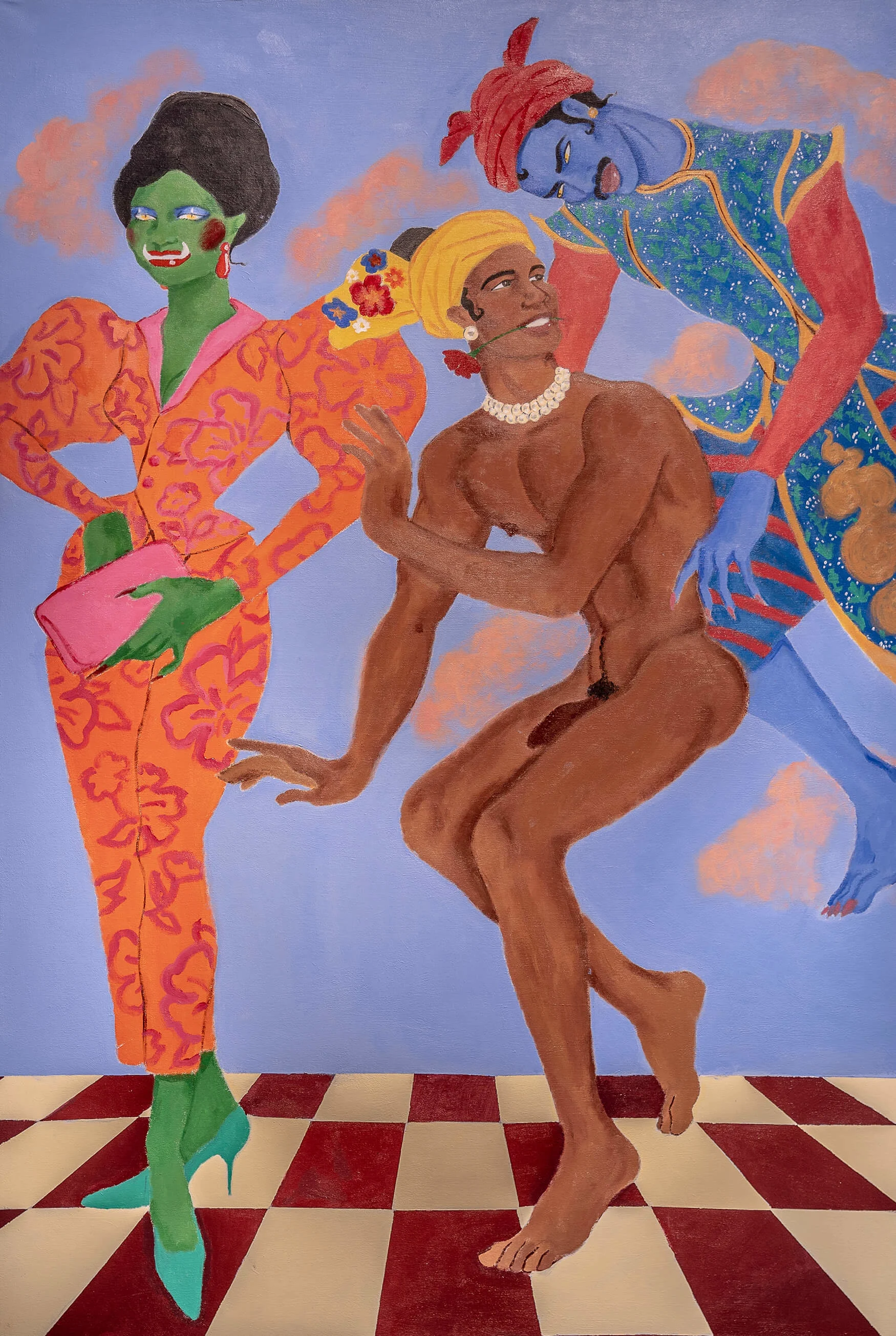

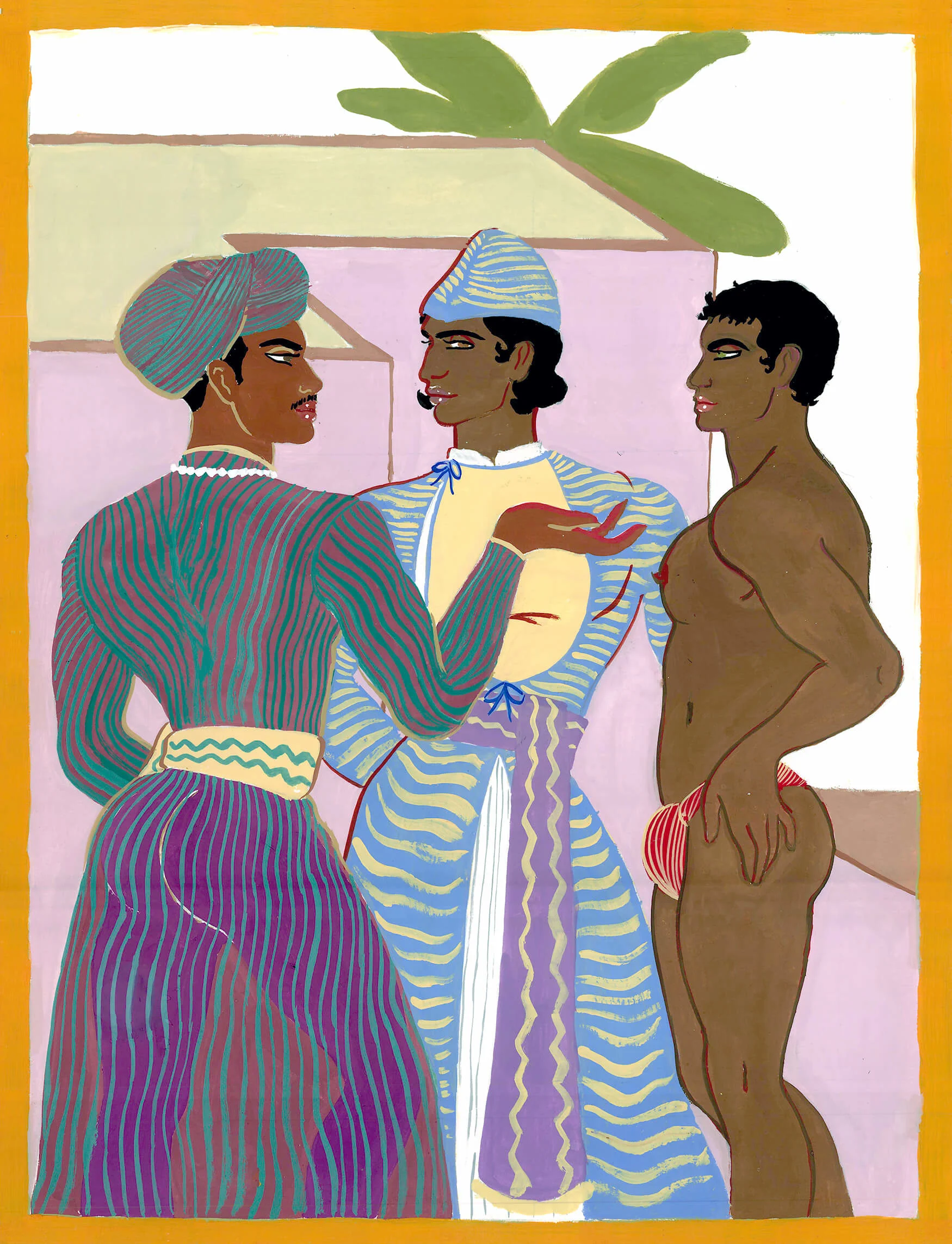

From myths and legends to childhood bedtime tales, stories are incredibly important to Richie. The scenarios and characters in his work are inspired by depictions of love within mythology and in Indian and Burmese miniatures. Many of his scenes originate in the Ramayana, the epic Sanskrit text which follows the story of Rama and Sita. The story is performed as a theatrical love story in Myanmar and has become part of Burmese tradition.

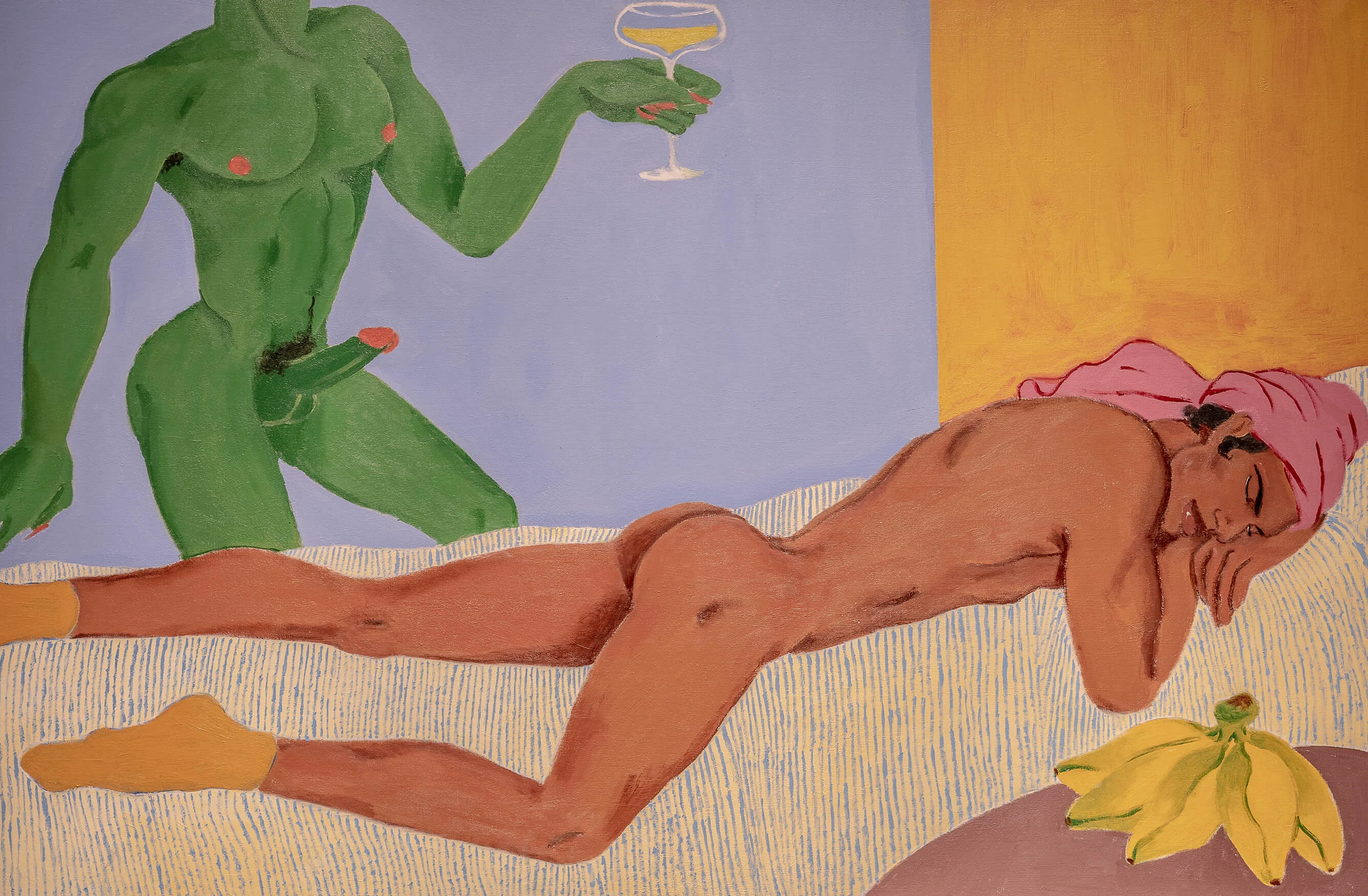

Richie borrows the tenderness from these love scenes but offers it to depictions of queer love, sex and sensuality. “You always see these court love scenes between men and women,” he says. “I just used that and then converted it into a more queer context. There were depictions of queer love in traditional miniatures as well, but they’re quite rare.”

I created this queer world because I’ve been made to hide and hate myself for so long.

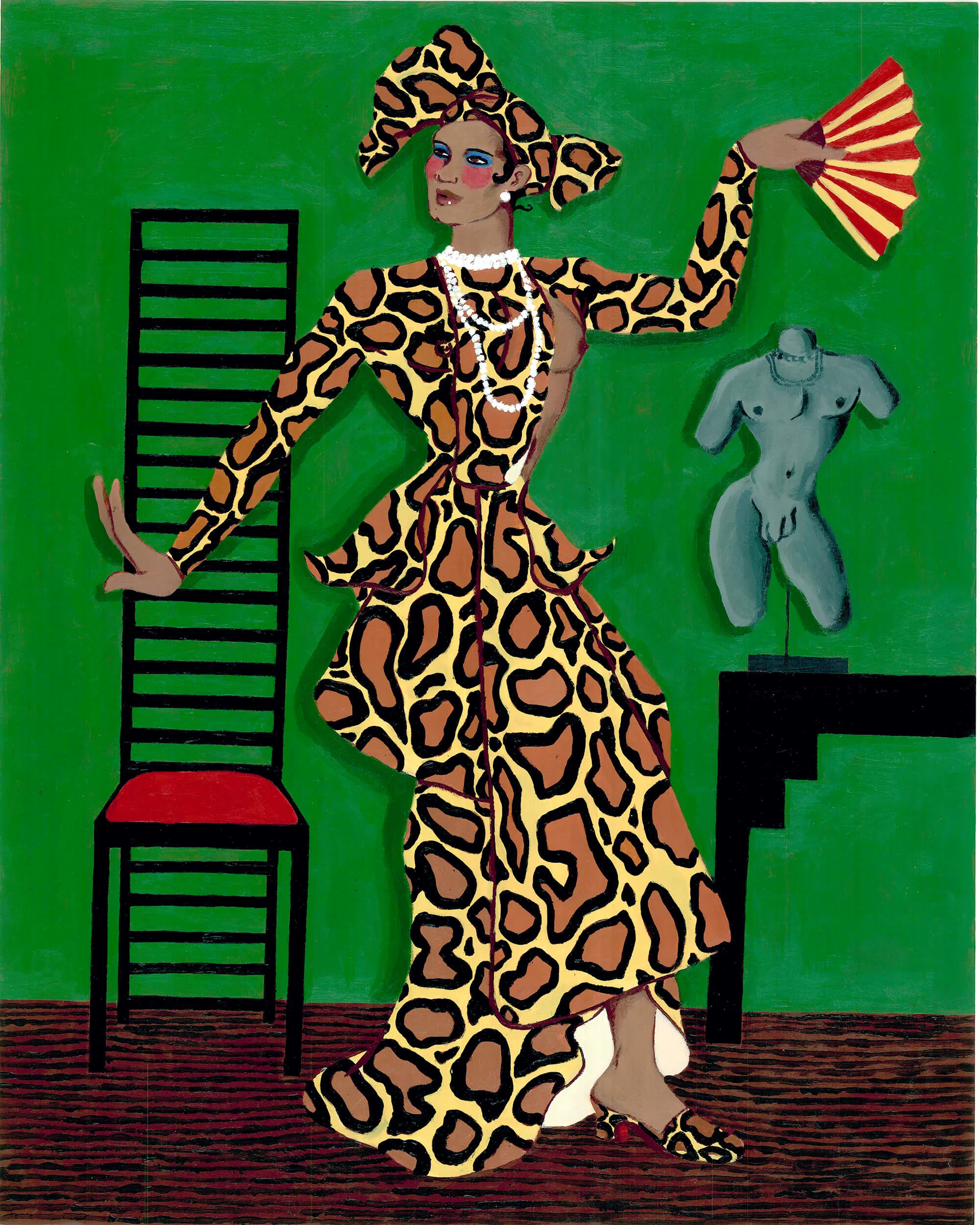

Being half Indian, growing up Richie was made to feel like an outsider for his darker complexion, his body hair, and for being gay in a tremendously conservative society. “I felt really unattractive. I was quite feminine as well, so all of that made me really hate myself when I was growing up,” he says. His art now is a reclamation of his identity: his figures are purposefully, unmistakably queer and Southeast Asian or South Asian. “I created this queer world because I wanted to see something explicit and raw, because I’ve been made to hide and hate myself for so long,” he says. “The parts that I was made to hate about myself – my Indian heritage and my queerness – I just want to express those in a vibrant way.”

Leaning into his education in fashion illustration, when Richie’s figures aren’t showing their beautiful, sculpted bodies in the buff, they’re clothed in fine garments and jewelry: sheer silks, patterned gloves and leopard print. He loves long toes and high heels. His inspiration comes from traditional dress, runway shows, the internet and postcards of women in the sixties in Myanmar. He revels in the beauty, fashion and theatricality.

His first solo exhibition in Yangon was titled A Chauk, a local derogatory umbrella term for queer people. It included mostly male nudes. Putting on such a daring show in Myanmar, he was a bit nervous. Homosexuality is illegal in the country, and he remembers having a conversation with the curator about the possibility of being arrested, but the reception was overwhelmingly positive.

Less than two years later, the gallery, Myanm/Art can’t exist as a physical space. Since the coup, they’ve been forced online, but are still bravely promoting Burmese artists’ freedom of expression, especially protest art. And though he’s far from home, for now, Richie continues to courageously face down ogres with love and beauty.