Chilean photographer Tomas Munita has visited Cuba a number of times over the last six years, but during a two-month stay he truly immersed himself in Cuban culture. His resulting series, Cuba On the Edge of Change, captures in very intimate ways how the island is rethinking its sense of self.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers' own words. See the whole series here.

I’ve been covering Cuba for the last five or six years, always during short trips. I didn’t go to Cuba with a clear idea of what I wanted to photograph; I was open to anything really. I wanted to stay in people’s houses, because when you travel in Cuba you usually stay in family places. I had no higher expectation; maybe I would find stories, but I was not sure what I would find exactly. I just wanted to be there in such fast-changing times.

It is a very important time for the country which is changing fast after Obama’s lifting of the embargo against Cuba. That has drawn so much attention to the country from all over the world.

In this light, we decided we had to do a more in-depth story about Cuba. To do this, I really wanted to spend time photographing, so together with my wife and three children we went there for two months. It was beautiful, it was an amazing experience for all of us.

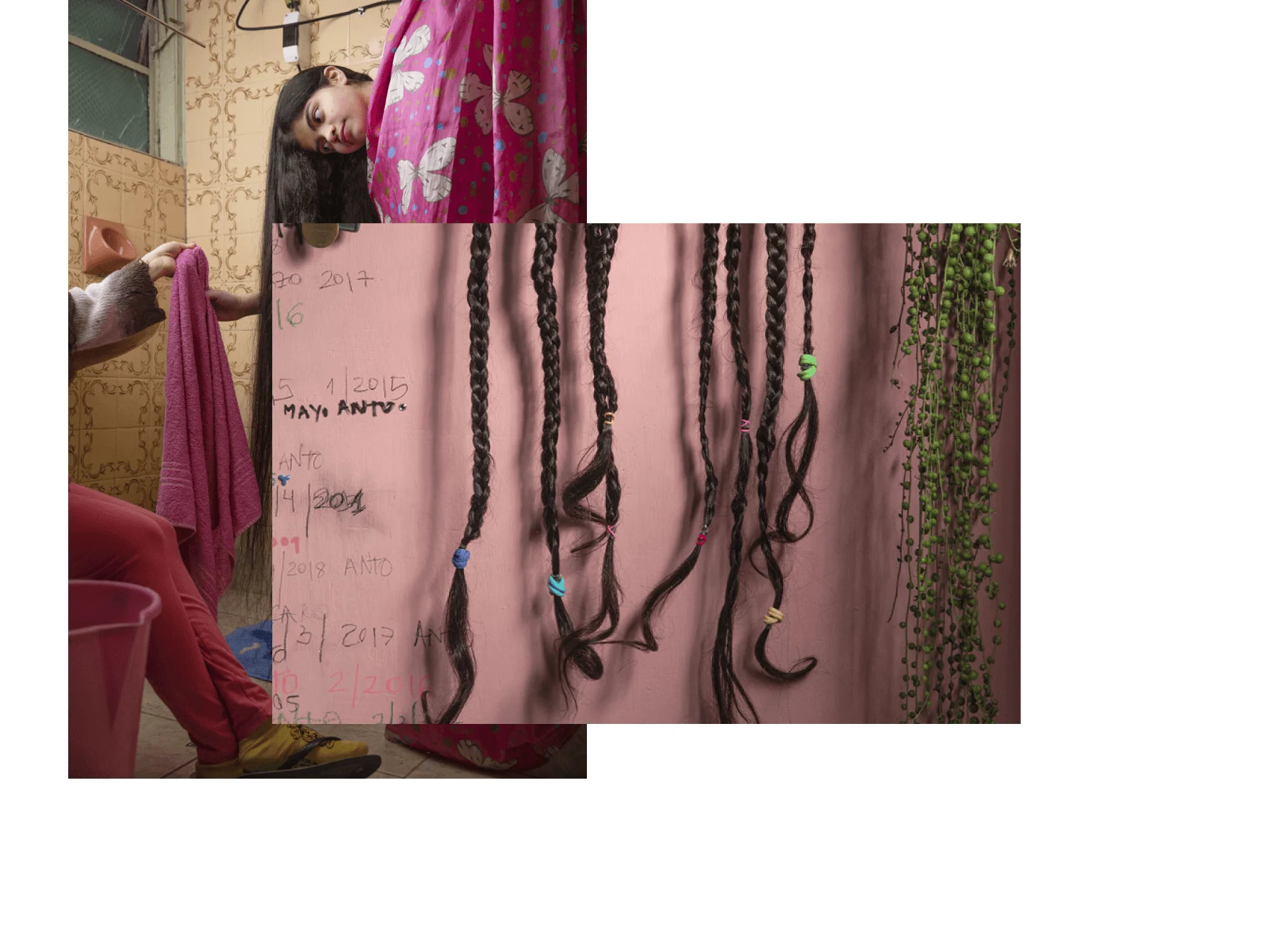

Traveling with my family was completely different than working alone. When I’m by myself, I just focus on taking photos, I’m chasing images all the time. But when I’m with my family, and with my children especially, it differs because you get to meet other kinds of people through them.

It slows me down. There’s no pressure. It allows me to get more into the rhythm of the place. You get tired looking for images all the time; the eye is in better shape when you take a step back. It allows you to see new things. When you have time to relax, your photography becomes better.

And that’s exactly what happened – I had other opportunities to the usual and another approach to the situation. To me it was beautiful. I could immerse myself into the place and was able to build a relationship with people, in a better way probably than when I’m just purely looking for images on my own.

The change in Cuba is very apparent, but not always necessarily in a good way. It was very striking to see how the buildings where I used to meet people had been displaced by tourism. A house where seven families used to live had been turned into a guesthouse and a fancy restaurant for tourists, but around the corner Cuban children were still playing in the streets. It is very striking to see this incredible imbalance between two worlds.

These foreign influences put pressure on Cubans, because it involves money and opportunity. However, it’s creating a weird unevenness. For example, people with higher education degrees, like engineers, now become taxi drivers. People just start working in tourism to make money. That’s very difficult to see sometimes.

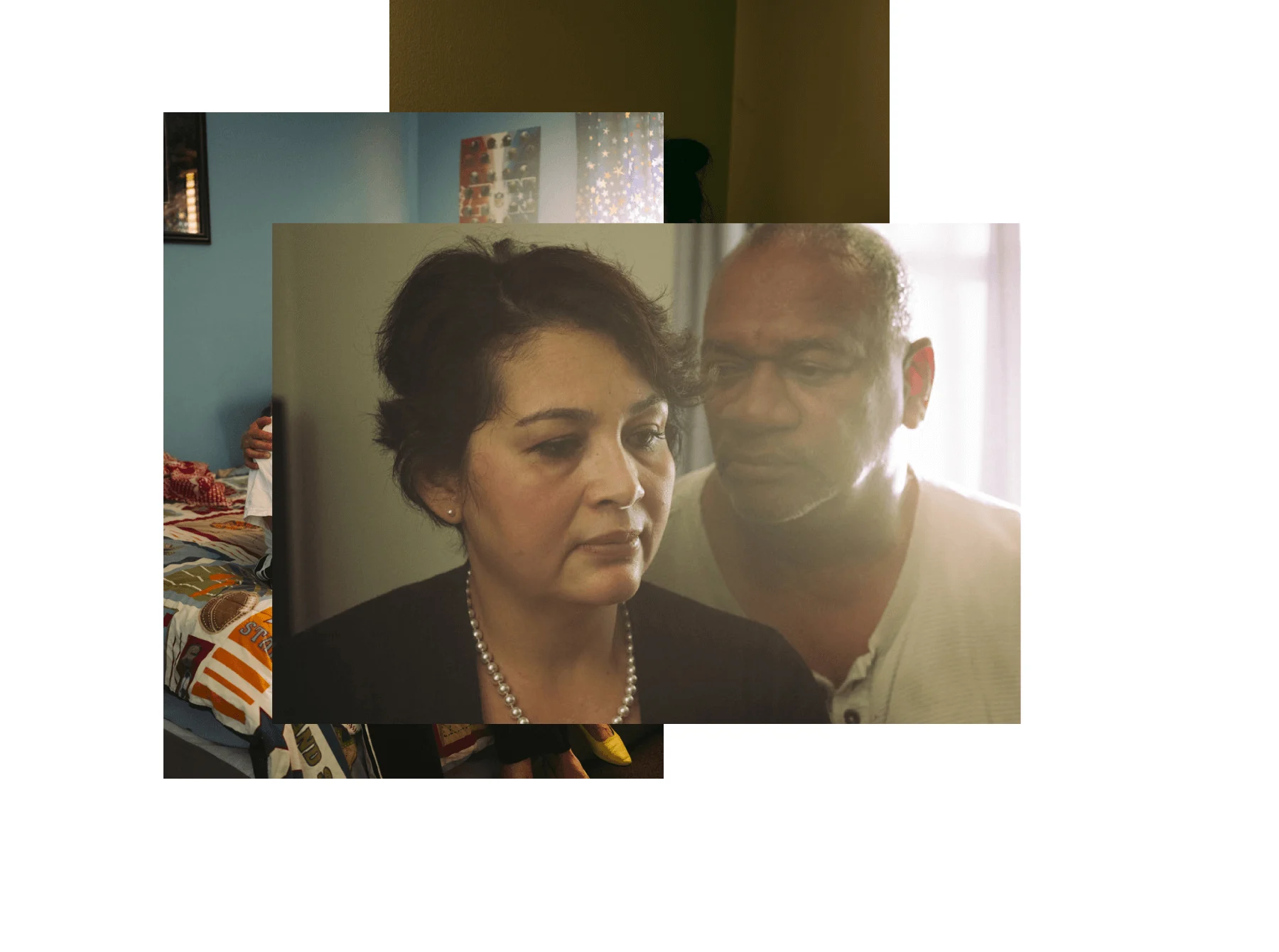

It was very emotional when Fidel Castro died. Literally everybody was out on the highway to see his coffin move past – the towns were completely deserted. It was surprising how much people loved Castro; they loved him as a symbol of that time. He was almost like a father figure to them.

I spoke to many people, from farmers to wealthy families with big houses, and some of them would even cry when I asked them how they felt. I never saw so much passion and admiration for someone, as the Cubans have for Fidel.