Some people know they will become photographers early on in their lives – others only pick up a camera much later. For 20 years, Dutch image-maker Carla Kogelman was completely immersed in the theater world before she changed career and started photographing.

Now she specializes in capturing the innocence of childhood told through the daily life of children who she photographs over long periods of time. Her series Ich Bin Waldviertel – which pictures two Austrian sisters, Hannah and Alena, over the course of six years – has been nominated by World Press Photo in the Long-Term Projects category. Read on about the project in Carla’s own words...

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers' own words. See the whole series here.

I used to photograph before, but I didn't understand why a photo failed when it did, because I didn’t know anything about aperture or shutter time. In 2007 I was exploring whether I wanted to do something else with my life and that’s when I applied for a six-day course at the photo academy in Amsterdam, with the assumption I would know all there is to know after that. Which of course wasn’t true. In the end I did the whole three years study there.

A few things were kind of taboo at the photo academy – kids and pets, subjects with a fluffy image.

I interned with Joost van den Broek. I was making pictures backstage at the Toneelgroep Amsterdam, but Joost told me to continue to photograph children. He said I had a gift in getting close to them, which is a lot trickier than with actors or models. That’s when I started photographing my nephews and another girl, Noelle, who I’ve been following ever since.

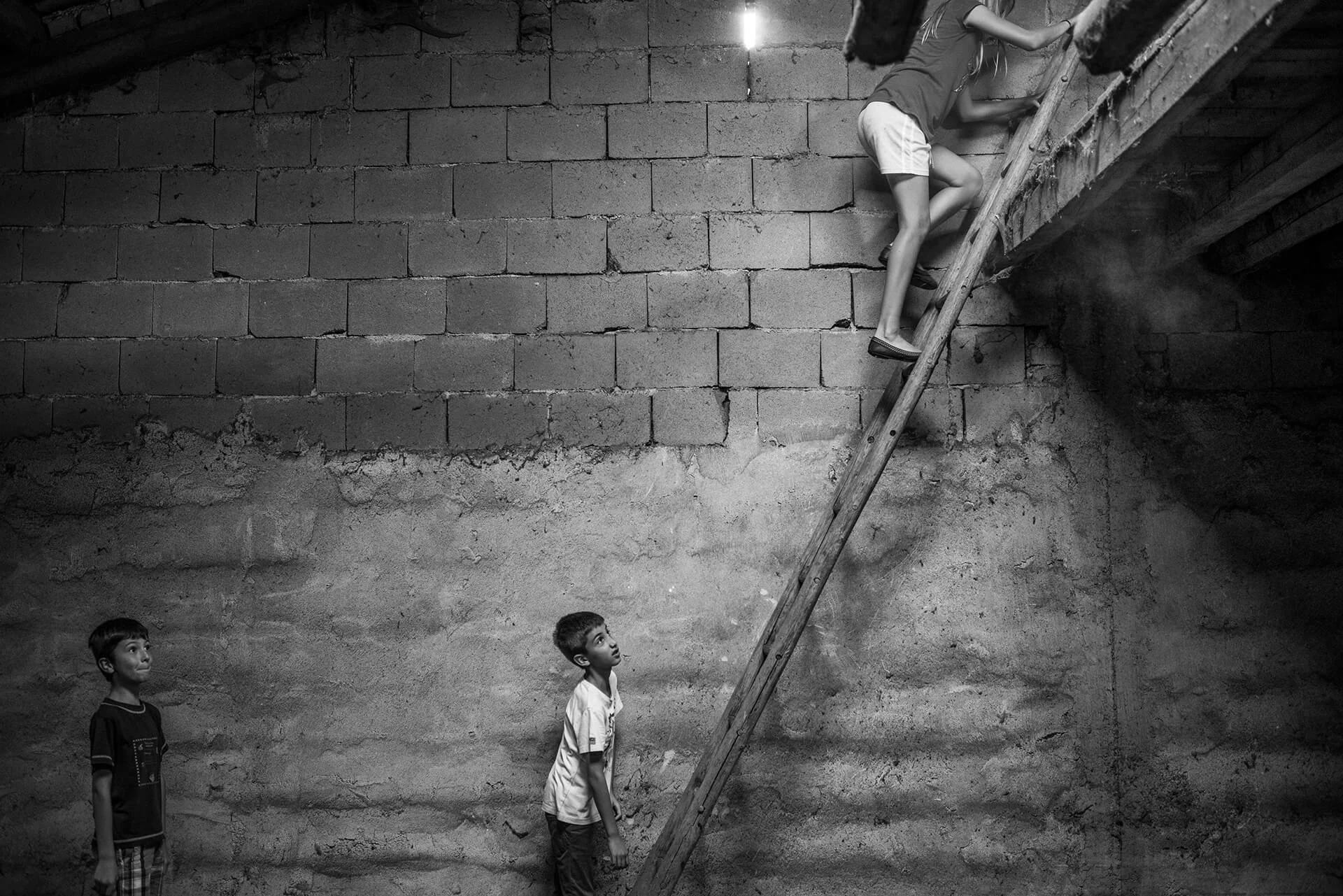

Children are different from adults in the sense they have some kind of authenticity; a casualness, which has often disappeared in grown-ups. A child can sulk in the corner of a room and that’s accepted, while an adult would be seen as some kind of idiot. A child looks and acts differently in the world. I think it’s intriguing to see how their world is, and I think we can learn a whole lot from kids. We lose a lot in growing up, which is a pity.

I always try to show a child’s strength and their positivity – the negative is portrayed quite often already. I think my power lies in being somewhere for a long period of time and becoming invisible.

Children are different from adults in the sense they have some kind of authenticity; a casualness, which has often disappeared in grown-ups.

When I finished my studies I was asked to photograph at a youth theater festival in Austria. They asked me to do a photo series about the region to be exhibited in September 2012.

Halfway through the summer I came across a small village. I grew up in a small town myself in Twente, and I had gone back to find and photograph my youth there, but that actually didn’t work out. The village still existed but I didn’t know anyone anymore and I wasn’t able to walk through my own memories. But when I came across this Austrian village, it felt like home.

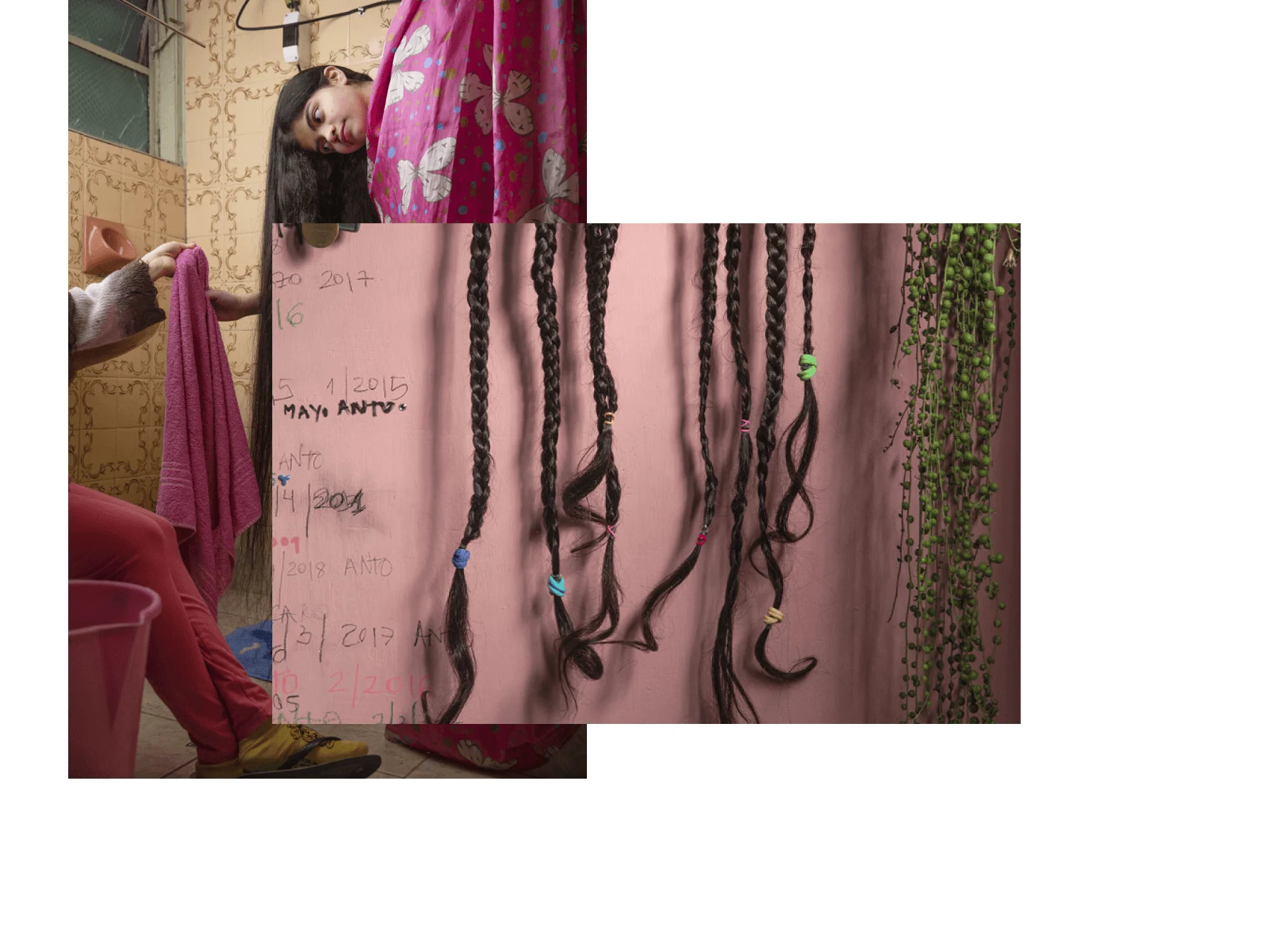

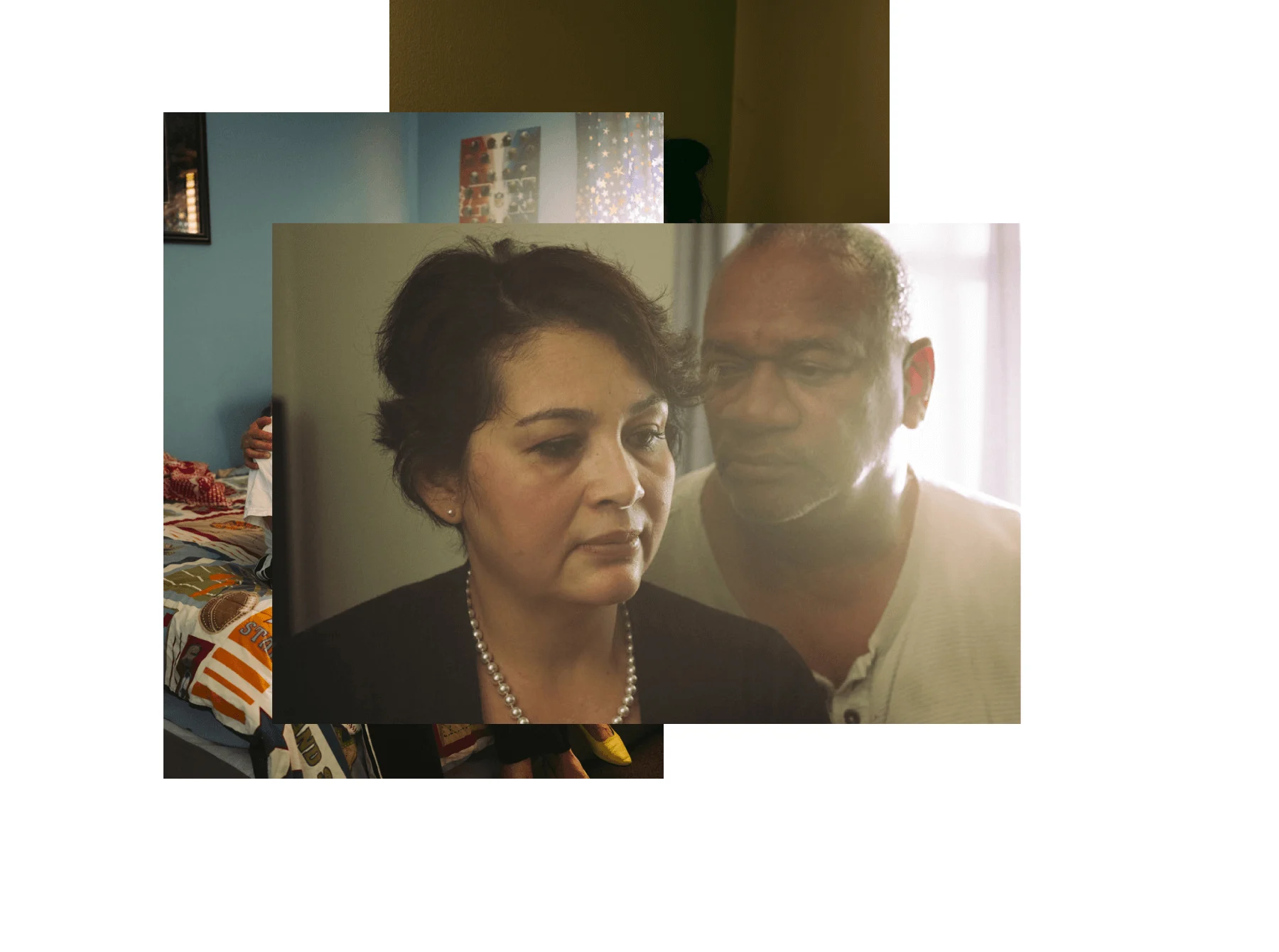

I met a woman with her two daughters, Hannah and Alena, and we chatted and she invited me to her farm around the corner. She said she’d like it if I would photograph her kids, because she didn’t have almost any pictures of herself growing up. When I showed her some of the prints I took, she invited me to stay at the farm in one of the guesthouses so I could be closer to the children while photographing them.

The kids start to trust me the moment I don’t betray them. I don’t intervene.

Ever since, I live for two or three weeks on the farm each year. I’ve been going there for six summers already. I eat with them, so noon their grandmother has made me a cup of soup too. I’ve become part of the family.

I follow the kids and their lethargy – there’s a lot of boredom there as well. Sometimes nothing happens. When the kids are watching TV all morning, I’m kind of done after a while.

The most exciting photos for me are the ones when something happens, like them playing in the water or when friends (who I’ve also seen grow up over the years) come over. I feel privileged I’m allowed to be there.

The kids start to trust me the moment I don’t betray them. I don’t intervene.

The girls love it. They are extremely valuable to me, and I’m valuable to them. That’s because I’ve been involving them from the beginning. Of course they don’t like every photo; and when they’re doing stuff that’s not allowed, they tell me not to take photos.

The biggest change has been how they themselves treat their bodies. Every year it’s exciting how I relate to them and they to me.

Hannah is the only one still living at home. Alena moved to boarding school last year and is only home during the weekends. She now has her first boyfriend.

If I look at pictures from 2012 now, I think woah, they were just little girls.

I’m going back this summer. It is always exciting to see what the situation is like now. The first day it’s about getting used to the situation, and you really see the differences from the year before. But when you see someone each day, it soon becomes normal again – you don’t notice how big they’ve grown or how they look different. If I look at pictures from 2012 now, I think woah, they were just little girls. And now the oldest, Alena, is a head taller than me.