For centuries, the Mayan beekeepers of the Yucatan Peninsula have been one of the largest producers of honey in the world. But in 2011, the Mexican government started encouraging farmers to grow soy beans, offering generous subsidies to those who did.

The Mennonites, a Christian group with a strong community in Mexico, were quick to embrace soy farming, but the consequences were extreme. This new type of agriculture damaged local forests, local people and local customs, especially beekeeping.

In 2015, the Mexican authorities changed course and banned soy production. But the Mennonites carried on, pitting the soy farmers and the beekeepers against each other.

Nadia Shira Cohen went to Mexico to document a situation where neither side really understands the full picture.

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers' own words. See the whole series here.

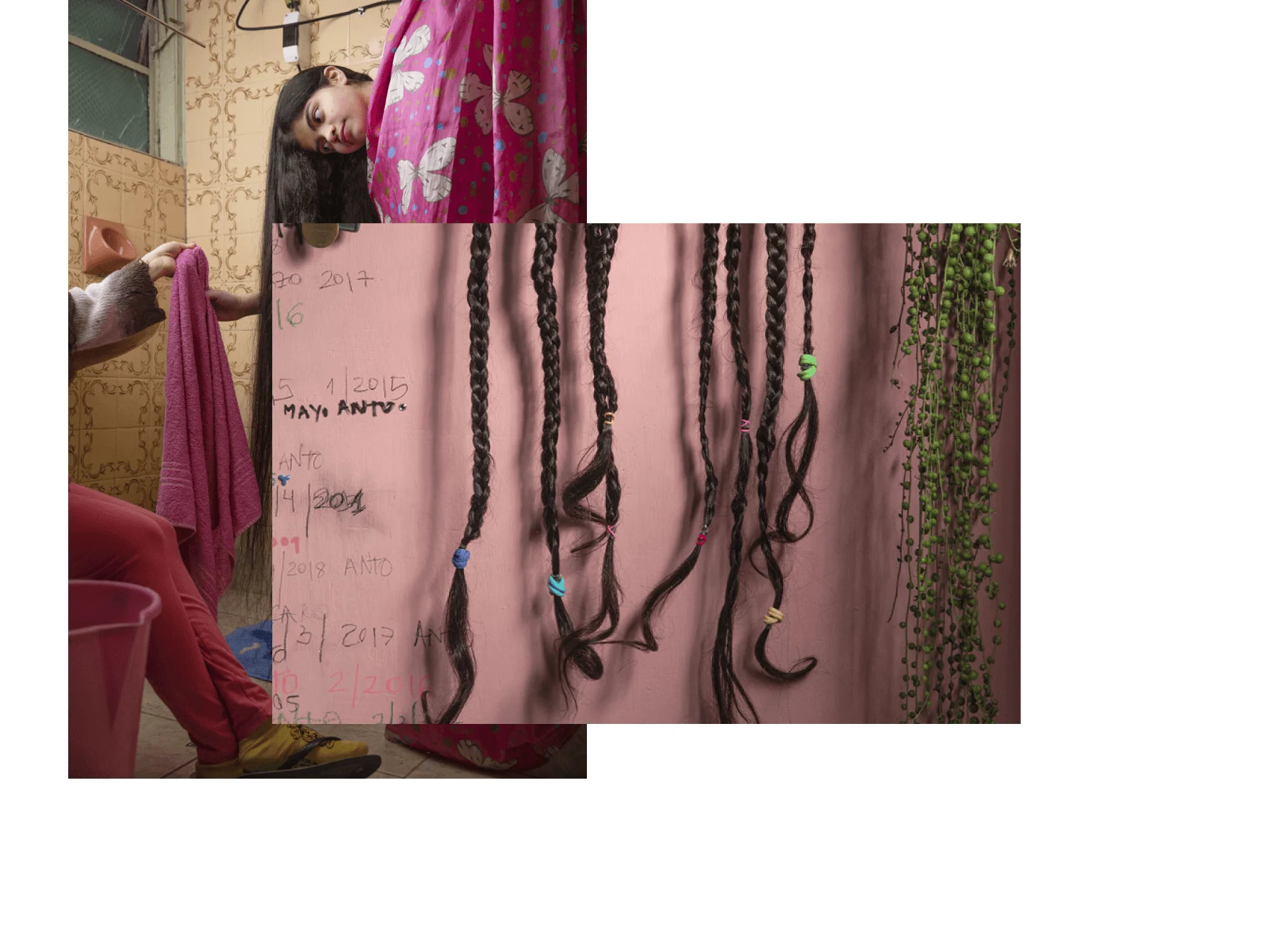

I stayed in Hopelchén, which is the ground zero of what's happening. You have Mennonite camps surrounding the area, as well as Mayans and beekeepers. I spent three weeks there. I don't think I've ever worked so hard on a story in my life, 14-hour days. Getting up at six and working until seven at night, every single day. And that's partly because the story is so complex and it requires really digging into both the Mayan and Mennonite communities.

There are two stories going on here. Two layers. One is about beekeeping and what's happening with the bees because of the soy, and then the other, bigger issue is the annexation of the land and deforestation.

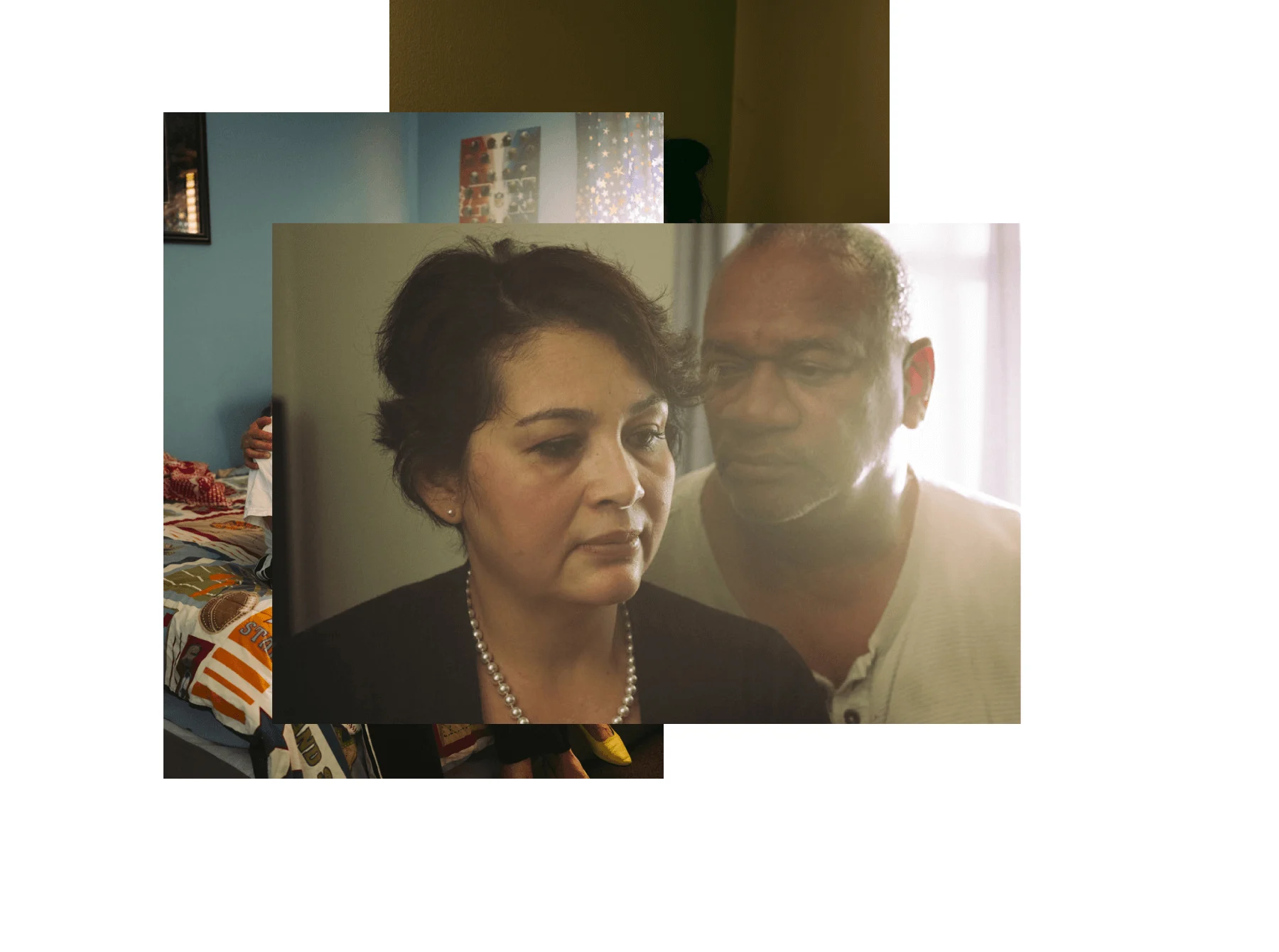

I wanted to show the gray areas in the story and not paint good guys and bad guys, because I don't believe either side is benefitting immensely from the situation. There are people being exploited on both sides.

I felt like I was going between two completely different worlds. It was almost like being in two countries, that are polar opposites, at the same time. I knew I was in Mexico, but it didn't feel like Mexico. Not the Mexico I knew, at least. Their worlds are intertwined, yet separate.

One of the challenges was to dedicate my time and energy equally to both communities. I think as photographers we're obviously visually driven, and for me, the Mennonite community was so new and visually interesting.

It's not an easy group to gain access to. They're a bit shy. They're much more reserved than the Mayan communities. They're working all the time, every 15 minutes the activity changes, and that's also very interesting to photograph. They're just working constantly – the women in the house and the men in the fields mostly.

I sometimes had to put myself in the shoes of the Mennonites and make myself understand their modesty and their boundaries, because it's not what my understanding of modesty is.

The Mayan community looked more familiar to me. So a personal challenge was to say to myself, I’m not just here to follow my eye, but to follow the story. To make sure I was really embedding myself in both sides.

The Mennonites are more orthodox, they don't drive cars. So they have to rely on the Mayans in the community to drive them. I actually chose a driver who was working with Mennonites every day, so he knew a lot of the families and he could give me a lot of information.

We went to a Mennonite camp and approached the governors. I was surprised they were quite open, because it's illegal to grow modified soy. They don't feel it's wrong. They say it's not scientifically proven that it's hurting the bees, or that it's creating any health risks.

This is where my feeling about Mennonites being used by big agri-businesses comes in.

I got in contact with this Mennonite family, and they were ok with me photographing them harvesting the soy. All the kids hopped inside the truck with the soy, so I hopped in too, and I spent an hour with these kids who are nine or ten. They’re sitting in this soy filled with insects and agritoxins and who knows what else.

They were a little shy at first but then suddenly they just start diving into the soy, playing in it. It really touched me. It dawned on me these kids are just kids growing up in a certain community and culture.

They were only a little older than my kids, so that was a very powerful moment for me.

A key moment on the Mayan side was the death of one of the beekeepers, because it was so symbolic. He died the day before the Day of the Dead. It was so shocking, and it posed a very sensitive access issue because it's always different when there's death, when people are mourning.

To get access at that time, and have this family be open was beautiful. His whole family were beekeepers. He taught his grandchildren how to keep. I saw the poverty of the family and the difficulties they faced and I realized beekeeping was this man's life. Obviously it was very emotional. It's said when a beekeeper dies, his bees leave. They know he's gone and they go elsewhere.