In October 2017, The New York Times published a captivating story about a group of young Nigerian girls kidnapped by the country’s terrorist group Boko Haram and forced to go on suicide missions. The twist was the girls escaped and survived. The accompanying photos – mysterious portraits of the girls against stark, simple backgrounds – were taken by Australian photographer Adam Ferguson.

Boko Haram strapped suicide bombs to them. Somehow these teenage girls survived was a 2018 nominee in the World Press Photo Award. We spoke to Adam about his portraits and what it was like capturing this unimaginable story...

Since 2016, we’ve partnered with the World Press Photo awards to tell the stories behind the best photojournalism around, in the photographers' own words. See the whole series here.

I went to Nigeria for another story with the West African Bureau Chief for The New York Times. In the process of not getting access for this main piece, I started working on a few smaller stories with the writer. We interviewed one of these girls and listened to her and it was extraordinary. I actually photographed one of them on the way to the airport to fly out. The photo was made in a real hurry, but I thought there’s something in this.

We decided to see how many of these girls there actually are – who had the same kind of journey to have been kidnapped and planted as suicide bombers, but didn’t blow themselves up.

It turned out there were a lot. I went back to Nigeria and managed to photograph another 17 girls who had been through the same thing, who could tell the same story.

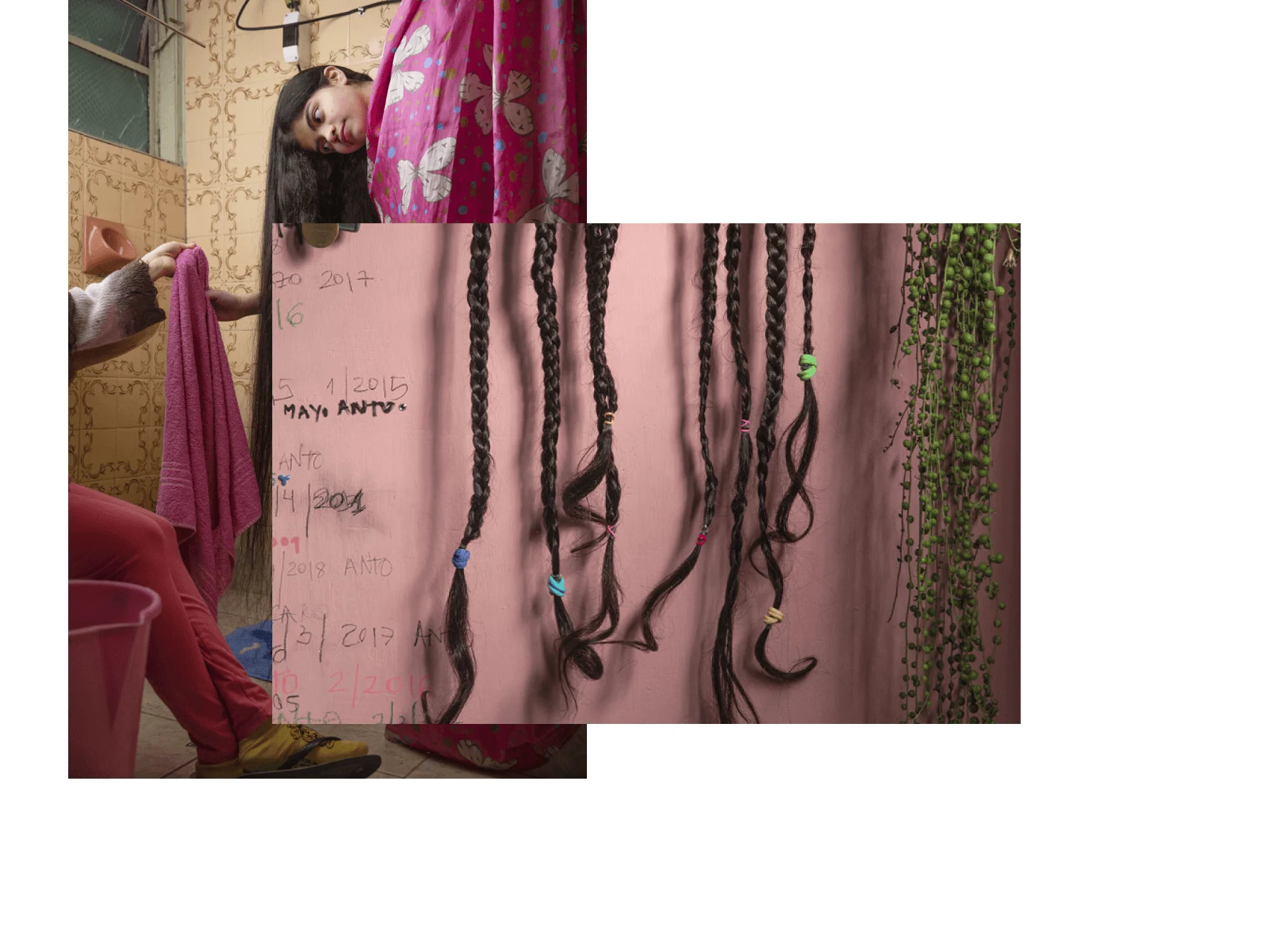

This was a different form of portraiture; it really became about the light and the sets and the mystery and the gestures these girls made away from the camera – not at the camera.

I used a couple of local Nigerians with connections in the security forces that knew where some of these girls were. After they've come out of Boko Haram, they're normally detained by the military, just to make sure that they're not symphatizers. The security forces are very worried that they will have flipped sides.

Because they are concealed most of the time, it wasn't like making a regular portrait where you really have to engage with the person, when the interaction between the subject and the photographer is vital. This was a different form of portraiture; it really became about the light and the sets and the mystery and the gestures these girls made away from the camera – not at the camera. For some of them it was a slightly confronting process, coming in, standing under a light and being photographed.

We obscured their identities because there are security issues with revealing who they are; they could be tracked down and killed because they'd be targets for Boko Haram.

I've already seen the criticism; it comes every year with the World Press. I was very aware of the fact that I’m a middle class, male photographer who is gazing at a black African and a woman as well, to take it to the next level. There's a very apparent power dynamic at play there, and obviously I'm in a position of power and they're not.

I wanted to celebrate these women for their bravery.

I haven't worked in Nigeria or Africa that much, so when I decided to return and make this story I really thought about how can I make this different, how can I create a picture that contributes to a new narrative and makes you think about these stories in new ways?

So I wanted to celebrate these women for their bravery. They've been through a lot, they're all very young. It was a terrifying experience to have explosives strapped to their bodies and to be sent off. They made the decision to give themselves up at the risk at being shot in the process of surrendering. So they're incredibly brave young women and I wanted to celebrate that. I want the photographs to feel brave and beautiful.

The pictures can stand alone as objects of beauty. They make us think about Nigeria, they make us think about women and Islam, they make us think about poverty – but knowing the story behind the subjects makes them more powerful than if we didn't.

When The New York Times ran the story, every girl had a quote. Looking at these anonymous portraits with beautiful colors and lighting and then reading the story it was kind of surprising. I think the story enhances the work.

In all honesty I don’t comprehend the grief that would bring. I've never been subjected to that kind of hardship.

I don't think it changed my approach to photography, but it was a heartbreaking story to work on. Listening to some of these girls' stories, some of the things they've been through, it's horrific. It's hard to imagine someone coming into your town and killing both of your parents and kidnapping you and your brother and lacing you in explosive. To be sent off to blow yourself up.

In all honesty I don't comprehend the grief that would bring. I've never been subjected to that kind of hardship. Thinking about it weighs on my mind, but I think this is perhaps the first story where I might actually be able to help.

I'm never really feel satisfied with my work. I always think of stuff I've missed or how it could have been better. But knowing that the work might impact the girls in a positive way, that brings a sense of satisfaction.