Many of us have grown up intoxicated by the delicious hell of what Hollywood has shown us is The Fashion World. The Devil Wears Prada, Ugly Betty...even 101 Dalmations showed us that working in fashion is like living on a knife-edge. Work hard and you might get somewhere. Slip up, and you’re toast. Here writer Otamere Guobadia sheds light on his own beginnings in the seemingly overrated “Fashion Cupboard,” and proves that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

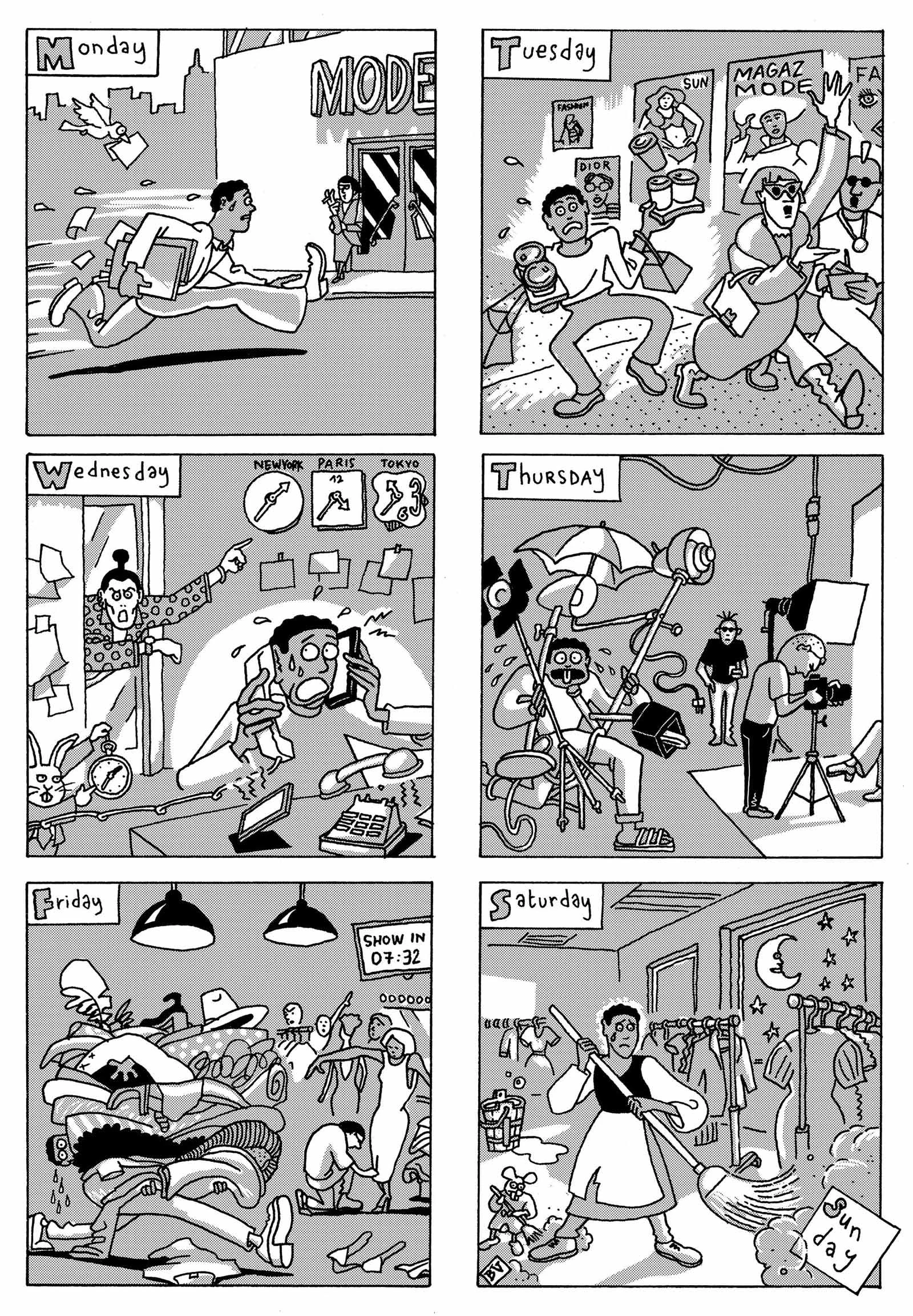

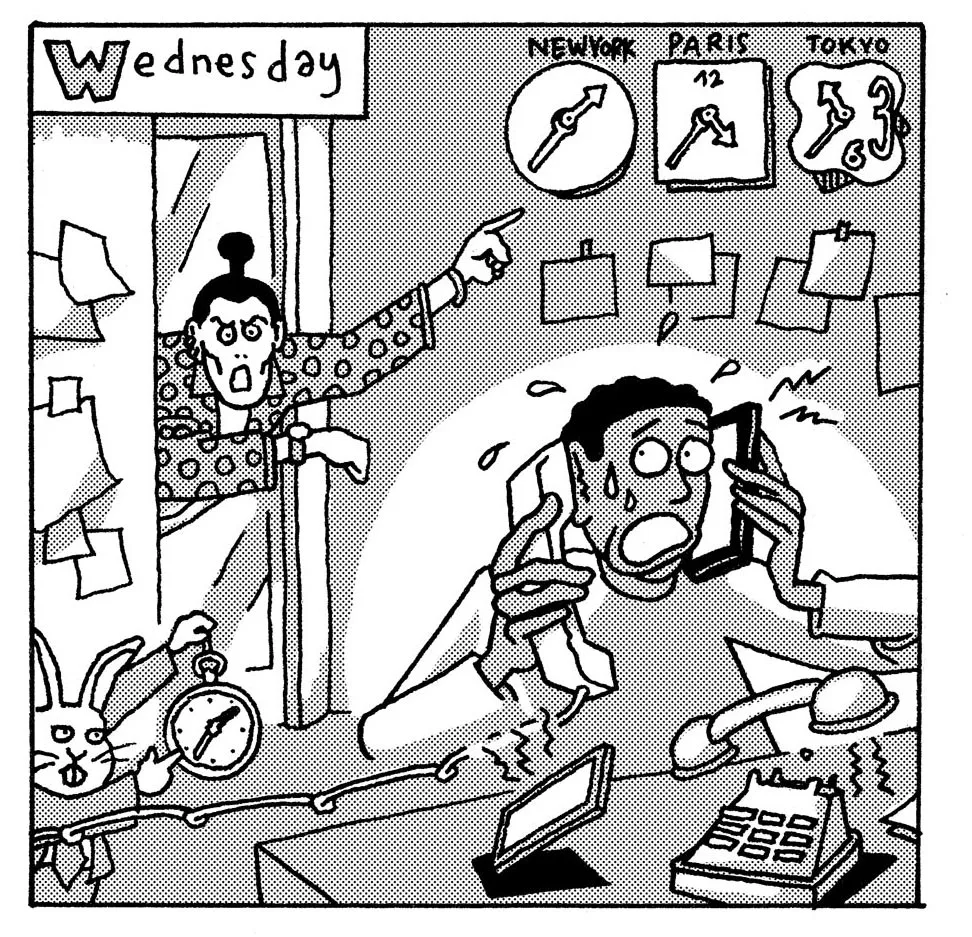

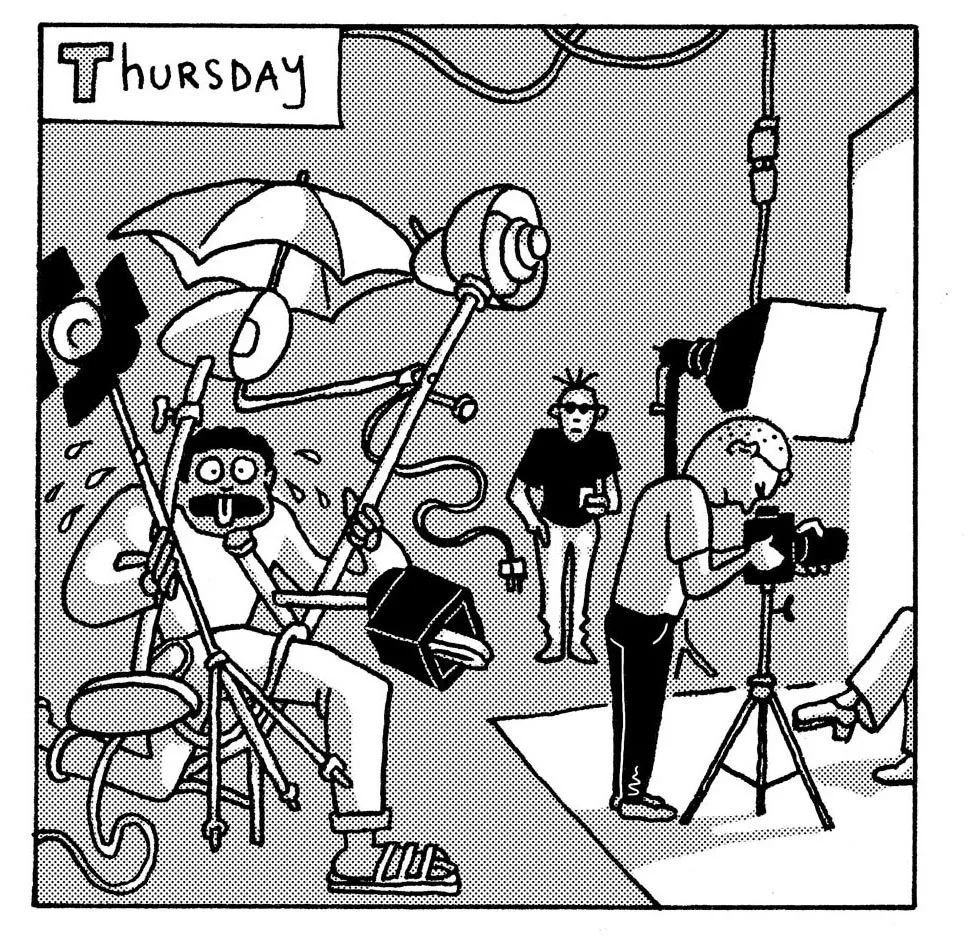

Comic by Baptiste Virot

In the summer of 2015, 20 years old and fresh out the gates of undergrad life and before I found my place as a writer, I traveled to London to channel my restless creativity into a burgeoning, sitcom-glamorous career in fashion. My law degree was completed and safely abandoned in the annals of my personal history to never be used or referred to again. There was no turning back. The corporate world could not have this pound of flesh! I was looking for an adventure, and when an opening for a six month internship at a fashion magazine presented itself, it seemed as good an opportunity as any to flex my creative muscle in a world that, for much of my adolescence, had enchanted me.

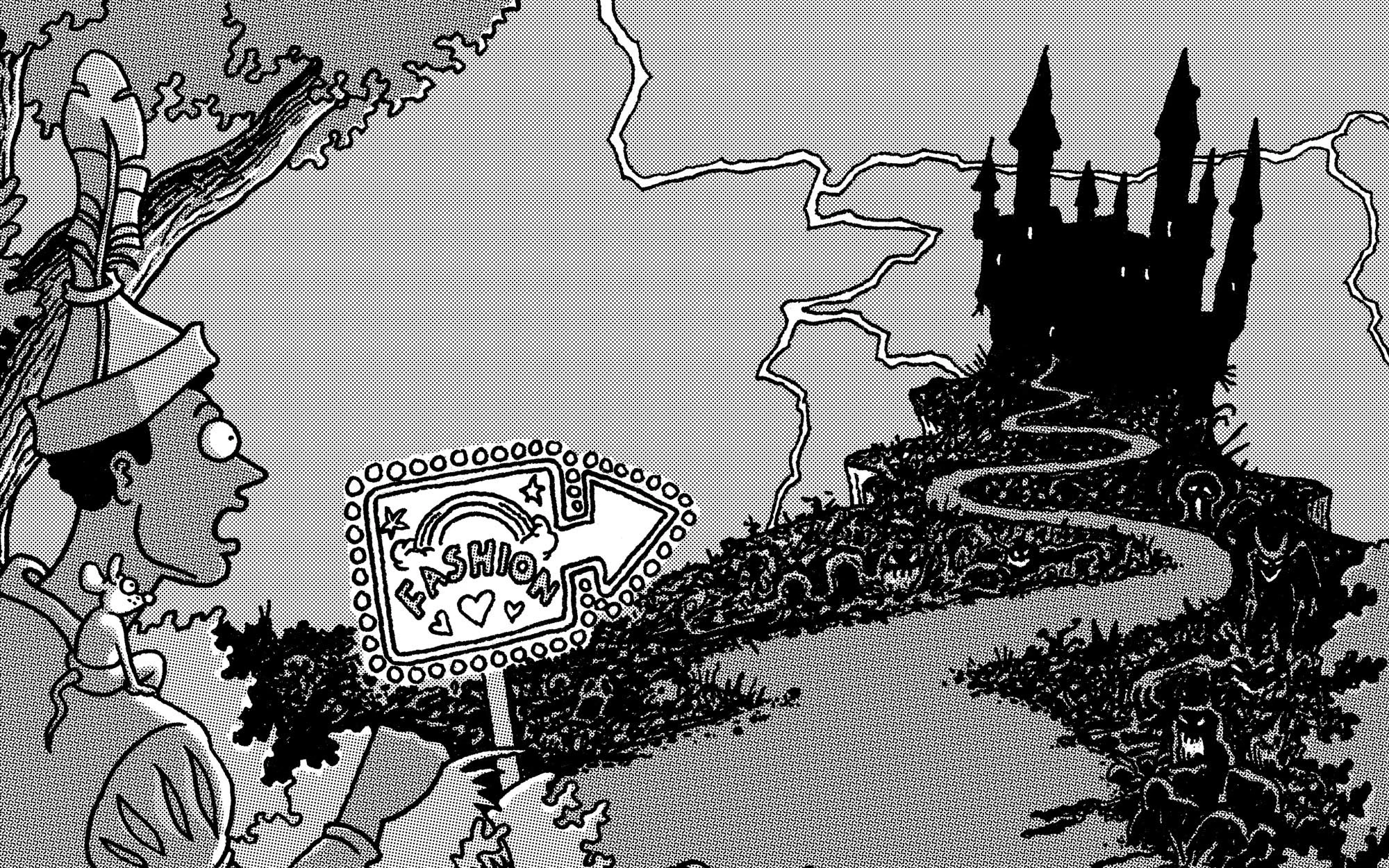

Fashion is and has always been, an industry intimately acquainted with “The Fairytale.” It is a world, by design, that cloaks itself in such shining, storied tropes: Atelier fairies draping and dressing rags-to-riches model princesses to descend high steps and dazzle all of eagerly awaiting society. Princely, rakish dandies flitting in the wings; enigmatic, white-haired kings appearing to the rapturous applause of front row subjects. Muglers and McQueens armoring – in the literal sense – women for battle. It is this high fantasy and the corollary promise of proximity to beauty and the beautiful that first draws in young, ingénue-like interns like myself. The tiresome lengths one is willing to go to to please in one's early days in fashion are predicated on the future promise of a season of plenty: an investment of effort and hours in the shadows in a bid to spend one’s future in the warm rays of fashion’s sun.

Fashion has always embodied and replicated fairytales not simply in form, but in function. Much like the tales it draws on, it embodies a fierce love of hierarchy, ugly step sister-like cruelties, and a total willingness to sacrifice its pawns for the pride, bounty, and flourish of its queens. For every rouge-templed Dianne Vreeland and floral-printed Hamish Bowles, and for every Champagne-fueled ball there are a hundred minimum wage interns hoping to catch a ride on an editor's coattails out of the fashion cupboard – if only for one evening. Every millennial fashion gaybie worth their pink Himalayan salt was raised on Ugly Betty and The Devil Wears Prada, stories that indulge in the soapy, emperor's new clothes politics of the fashion industry, longing to live the lives imitated in their art.

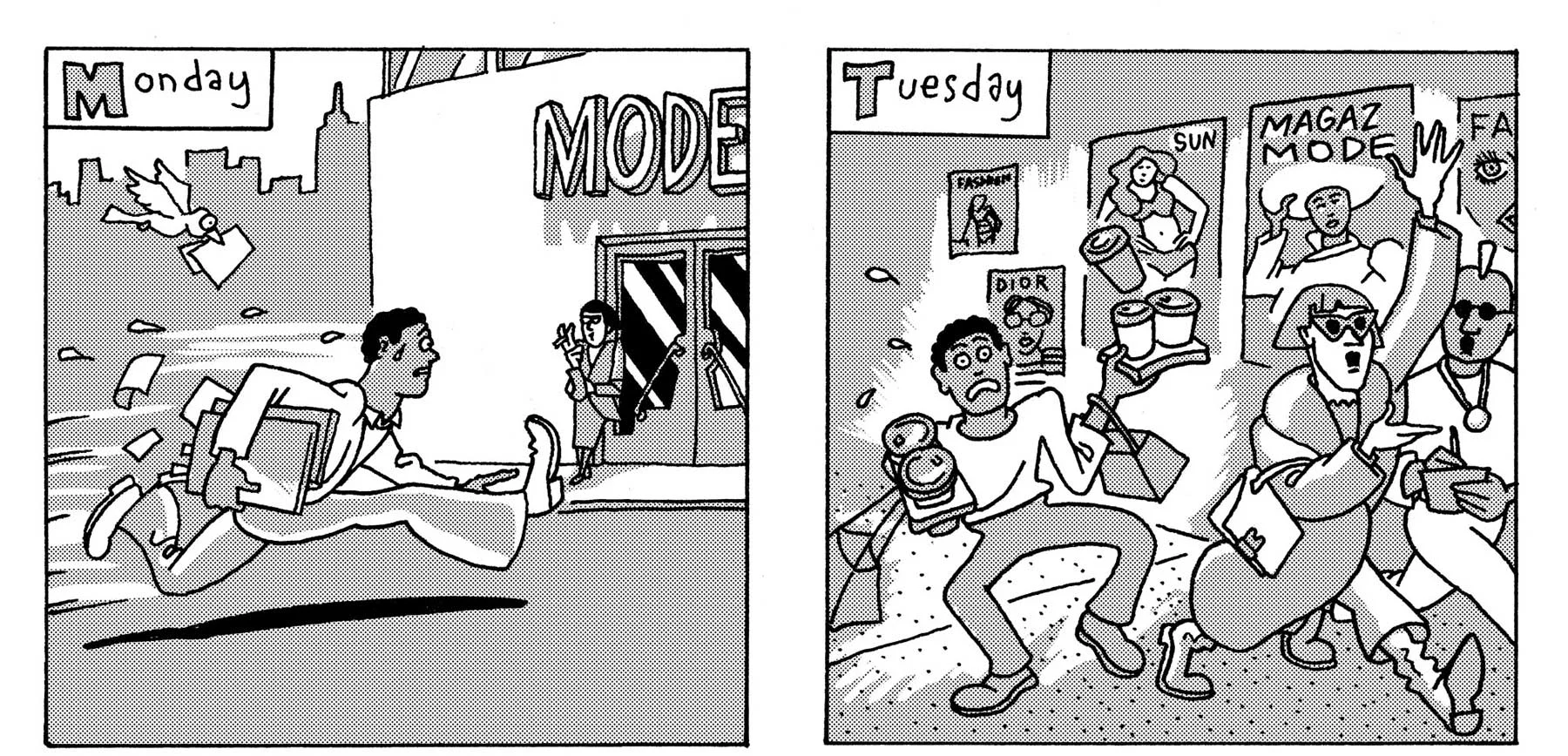

It was through shows and movies like these that I was first introduced to the concept of the “the fashion cupboard” – a technicolor explosion of silk and satin drapings, garment bags, samples, silvers, stones, and designer accessories housed in a fashion magazine’s HQ. In the 11th episode of Ugly Betty, aptly titled “Swag” – the rabid, glamour-hungry employees of the fictional MODE magazine, bargain and wage war for all the latest season's must-haves, samples and gifts accrued in their publication's massive closet.

For every Champagne-fueled ball and Battle of Versailles, there are a hundred minimum wage interns hoping to catch a ride on an editor’s coattails out of the fashion cupboard.

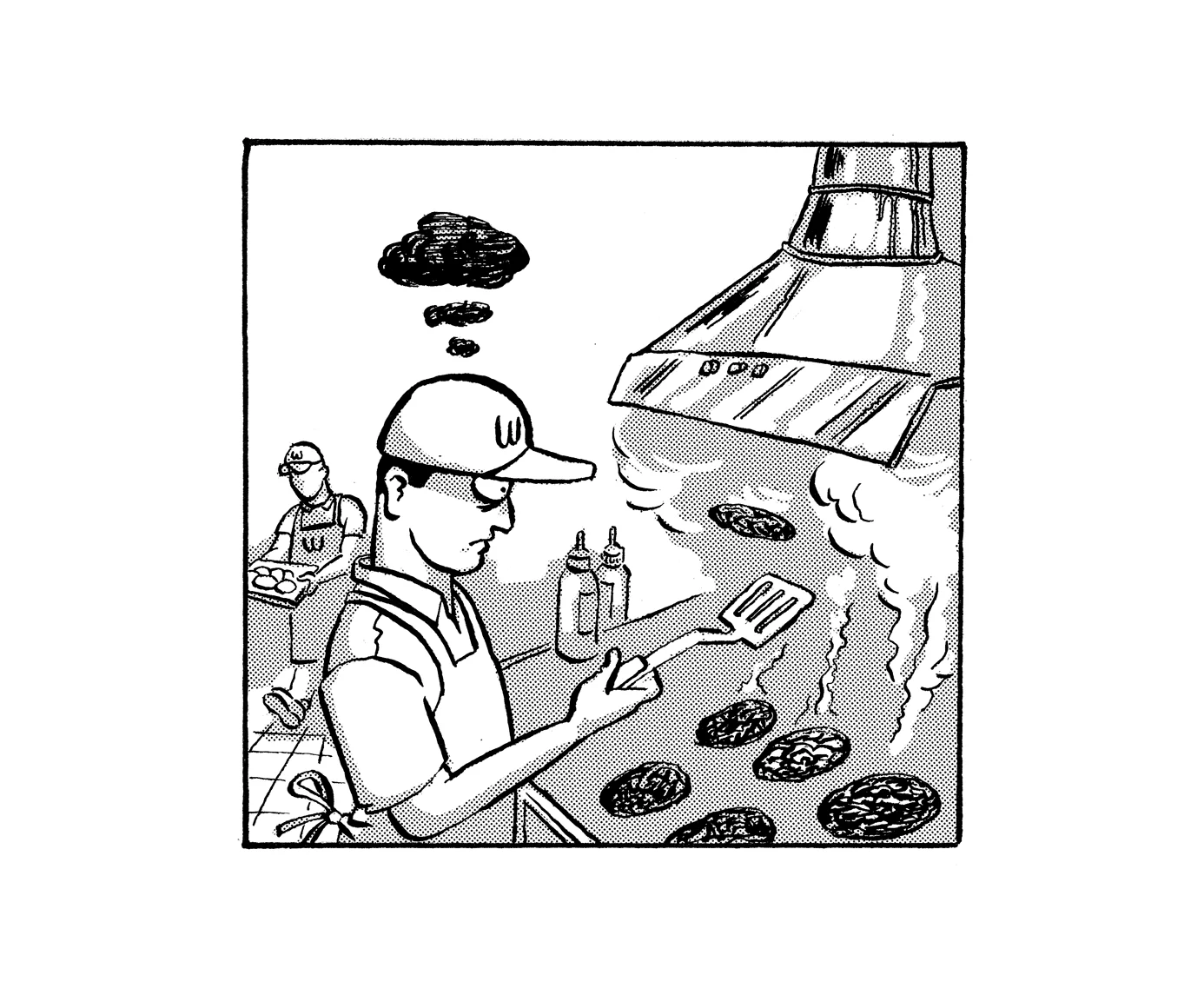

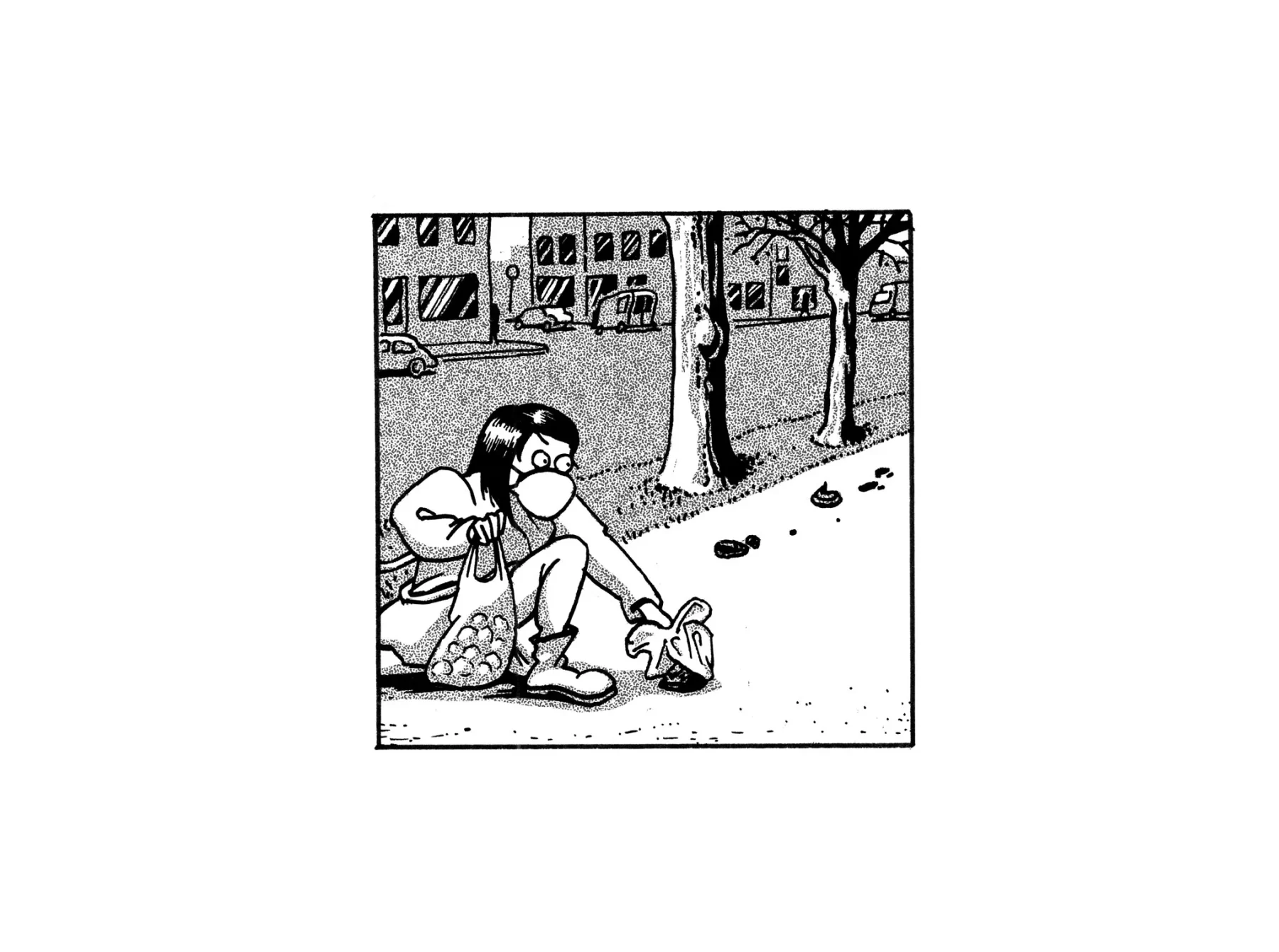

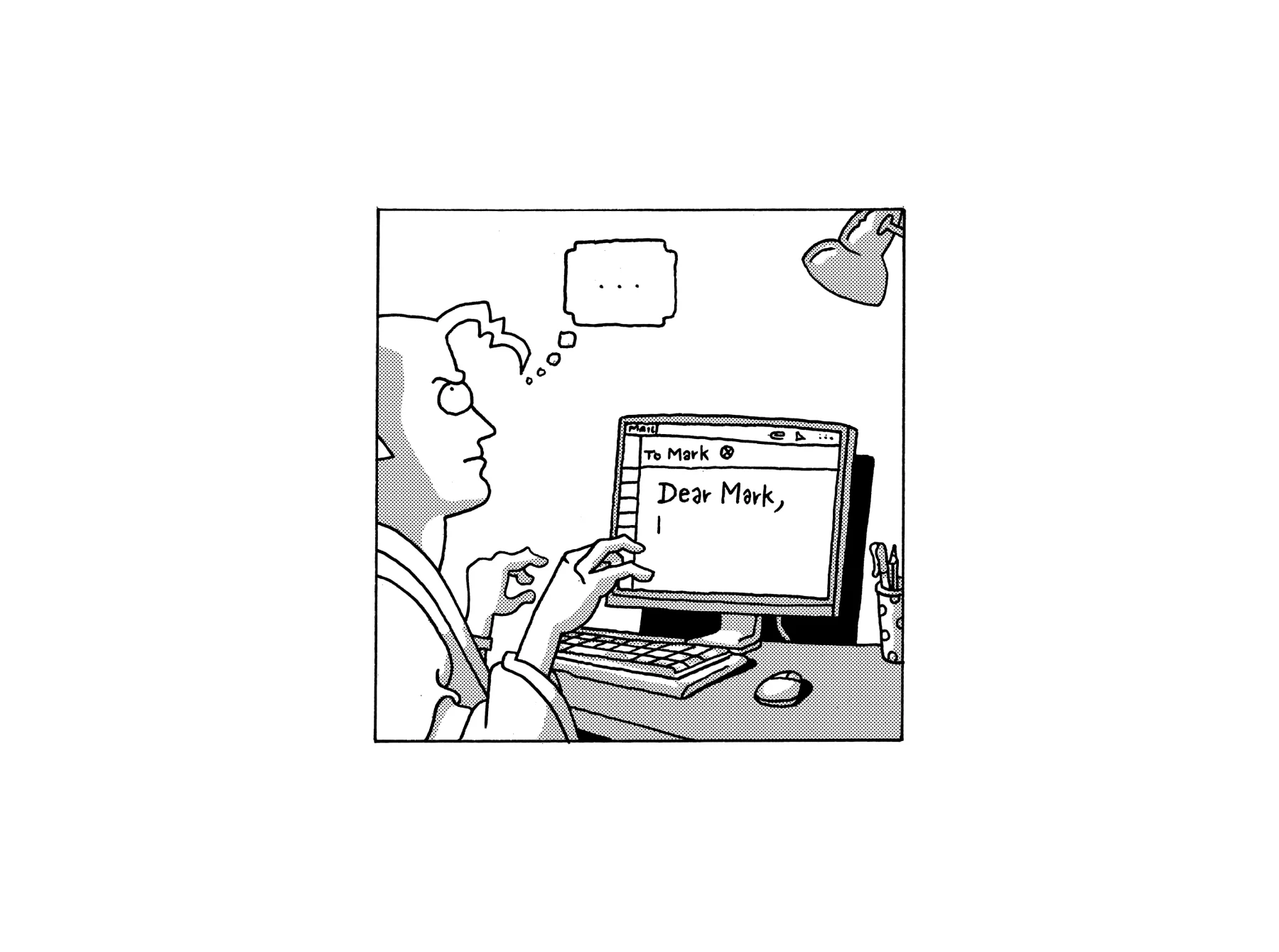

The reality of the fashion cupboard that I would walk into nearly a decade after watching Ugly Betty was no such gilded enterprise. It was a small, windowless box in which I was to spend thousands of hours meticulously logging, steaming and organising thousands of fashion samples, emerging only when editors required either physical labor, tedious thankless tasks or to buy a £3 meal deal with the pittance I was being paid. It was the troll under the bridge territory. I was a gremlin in the shadows feasting on the crumbs of opportunity and glamorous anecdotes dripped down by higher-ups. For six long and dreary months, life was circumscribed by these four unimpressive walls, fortnightly turned-over interns for me to train up each time, and the often hair-brained scheming and delusions of wicked step-sister editors. In many ways, starting out in fashion was more akin to some Brother's Grimm pantomania than anything resembling real life. The promising believability of its shiner, glossy elements – the booze, the clothes and ways in which you are encouraged to play at flattery and favourites like a courtier ascending the ranks and trading favours – held a captive romance. It encouraged you to hold through, to work harder with little reward, to ignore instincts to quit and run for the hills. You were fully through the looking glass, why turn back now when there may be delights ahead? I toiled and tagged, steamed, zipped, and bagged. I attended to the minutiae of staff members’ days, the hazing rituals, and the banal delegations. I painstakingly memorised green juice orders and supergreen protein pot specifications and, one time, helped an editor move the contents of their house (using our publisher's often-abused and expensive in-house couriers) hoping that one day my efforts would be rewarded. Reader, my fairy godmother never came.

What shows like Ugly Betty and films like The Devil Wears Prada, get most right about their portrayals of the fashion industry is not just the willingness of its interns to go above and beyond the call of duty.

Every year, our fashion magazine would host a complimentary party for a prestigious awards ceremony. As the date drew closer, I admittedly excited myself with visions of what was sure to be a night to remember. Whatever menial, tedious task I'd be assigned would surely pale in comparison to the glow of the stars I'd catch glimpses of, the small, meaningless talk I would overhear, the effortless beauty and glamour they would perform around me to my nourishment.

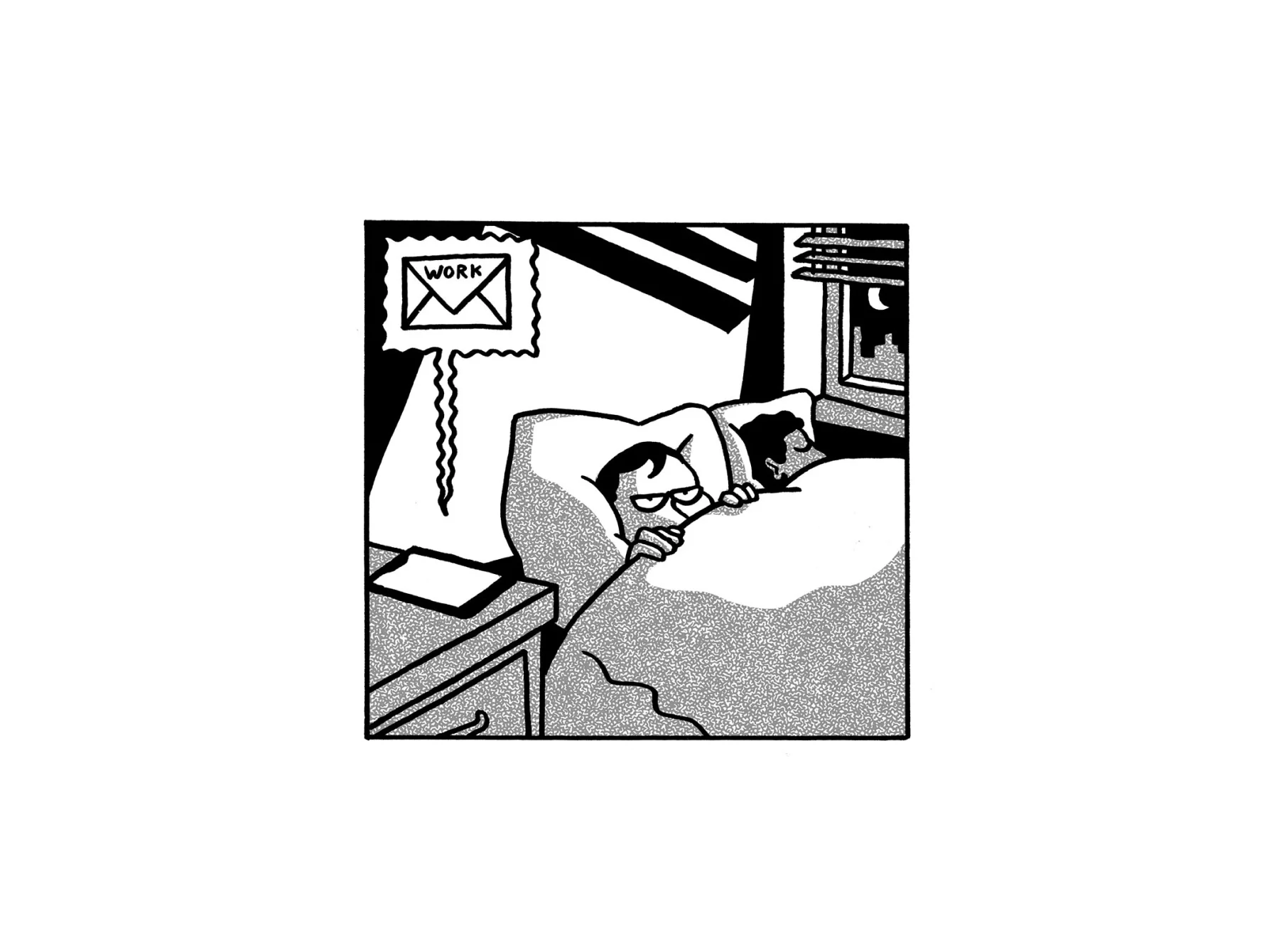

But as the clock ticked and I diligently and enthusiastically steamed more dresses, blouses, and outfits – one for every single member of my team, for editors and assistants both junior and senior – the simple reality was dawning on me. I was not to go to the ball. I was to steam dresses in my little corner. A, our Fashion Director, walked in and confirmed my suspicions, stating bluntly that there was “no job” for me there and I would not be allowed to attend. To further my heartbreak, an editor from another team for whom I'd called in a lush fur stole for the evening, waltzed into the fashion cupboard to put on the dress that I'd of course steamed for her. “Are you coming to the party?” she asked. I said no. She giggled and remarking without much sympathy or apology, called me “Cinderella.”

In many ways, starting out in fashion was more akin to some Brother’s Grimm pantomania than anything resembling real life.

For all of my whingeing, it wasn’t all bad. On good days it felt like we were creating beautiful art. Indeed, we were. There was one particularly beautiful, cold crisp day spent by the sea shooting on Broadstairs beach, being whipped by blue, salty, life-affirming air. There were also rare moments when my opinions on vital questions of taste and aesthetics were called upon and willingly indulged. There was the mid-ranking member of the beauty team who went above and beyond in her kind words and generosity. There were also the conversations that descended into the kind of side-splitting laughter you could only have with other lowly colleagues in the trenches with you.

Some harrowing episodes take on a deep hilarity in hindsight. There was the case of the missing Céline earrings, which vanished in the fashion cupboard hours before they were due to be loaned to French Vogue. What felt at the time like an ostensibly critical and high-octane moment makes me laugh now (the earrings were frankly, quite plain and ugly). The hours following the earrings being reported as missing saw me cosplaying as an underpaid, young Poirot tribute act, super-sleuthing around the cupboard, in and out of cabs between PRs and fashion houses we hoped we'd sent them to by accident; reviewing hours of CCTV footage, poorly taken inventory dockets (perhaps my intern training could have used some work!), identifying what shadow in bizarre scanned jewelry images we used to record the inventory, might be the mislabelled, missing earrings. The earrings were later found in a sock drawer they'd likely been knocked into by an editor. Deeply anticlimactic.

I once witnessed an editor throw a tantrum on the office floor about how wide a model's ankle looked in a shot for a commercial spread. Another time, I was given largely glowing reviews during a progress feedback meeting, except for my lack of awareness and professionalism with regards to something I had said that had terrified an editor. A few weeks before she had mentioned a mirror in her house had broken but had said it had fallen unaided therefore she dodged the seven years of bad luck. I had helpfully piped up that a mirror falling unaided in fact signified someone’s imminent death. She had complained that I had caused her to worry for the lives of her family; a truly absurd criticism to launch in an otherwise perfect appraisal about my ability to work. Fashion does not encourage know-it-alls. In hindsight, it is striking perhaps how often the knowledge possessed by underlings, any instinctive grasp at a solution or innovation, was always to be kept quiet and disregarded, superseded by the age and status of long-tenured players.

As long as fashion continues to satisfy a seemingly spiritual hunger for beauty...there will always be young, eager interns ready to be chewed up and spat out.

What shows like Ugly Betty and films like The Devil Wears Prada, get most right about their portrayals of the fashion industry is not just the willingness of its interns to go above and beyond the call of duty, it is their often unrewarded ingenuity, out-of-the-box opinions, and idiosyncratic knowledge that could transform the houses and publications that they work for – if they ever saw the light of day. Whatever labor other interns of other industries do, fashion interns, do them backwards, and (sometimes literally) in heels. On their shoulders stand the ladders that those in spotlight climb to acclaim, and for a lucky, determined and brilliant few, the ascent and the power may one day be theirs, for the steep cost of their dignity. They steam, they polish, they lift, they flatter, all the while nourishing their own small, fledgling dreams of greatness – and keeping up with the Jones' and the Kardashians to boot.

As long as fashion continues to satisfy an almost spiritual hunger for beauty and the beautiful and hold a singular ability to buy and sell us dreams of who we are and might be transformed into by apparel and aesthetics, there will always be young, eager interns ready to be chewed up and spat out. Those six months spent in the fashion cupboard prepared me for the myriad of disappointments of later working life, taught me to find meaning in things other than work, and summoned a will and resilience which is yet to desert me. It taught me when to move on and – more importantly – provided an education in that old, oft-repeated lesson, “all that which glitters…”