It’s all too common for editors to box in writers of color, assigning them stories that align with their perceived identity and assumed experiences, rather than their expressed interests or expertise. But in an increasingly competitive media landscape, saying no to “race issue” assignments can be a fraught decision. Here, journalist Ammar Kalia explores his own ambivalence toward identity-based commissioning.

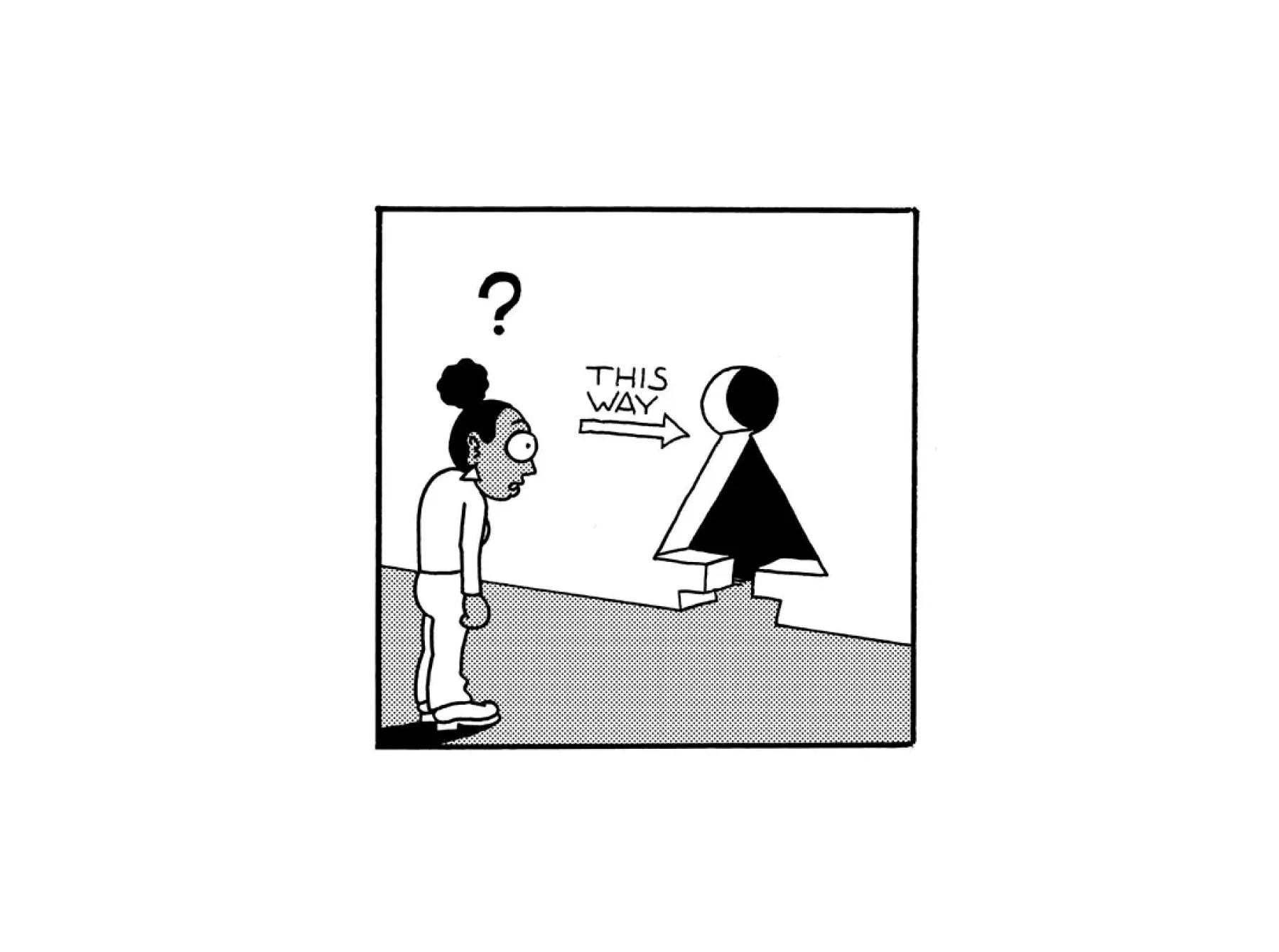

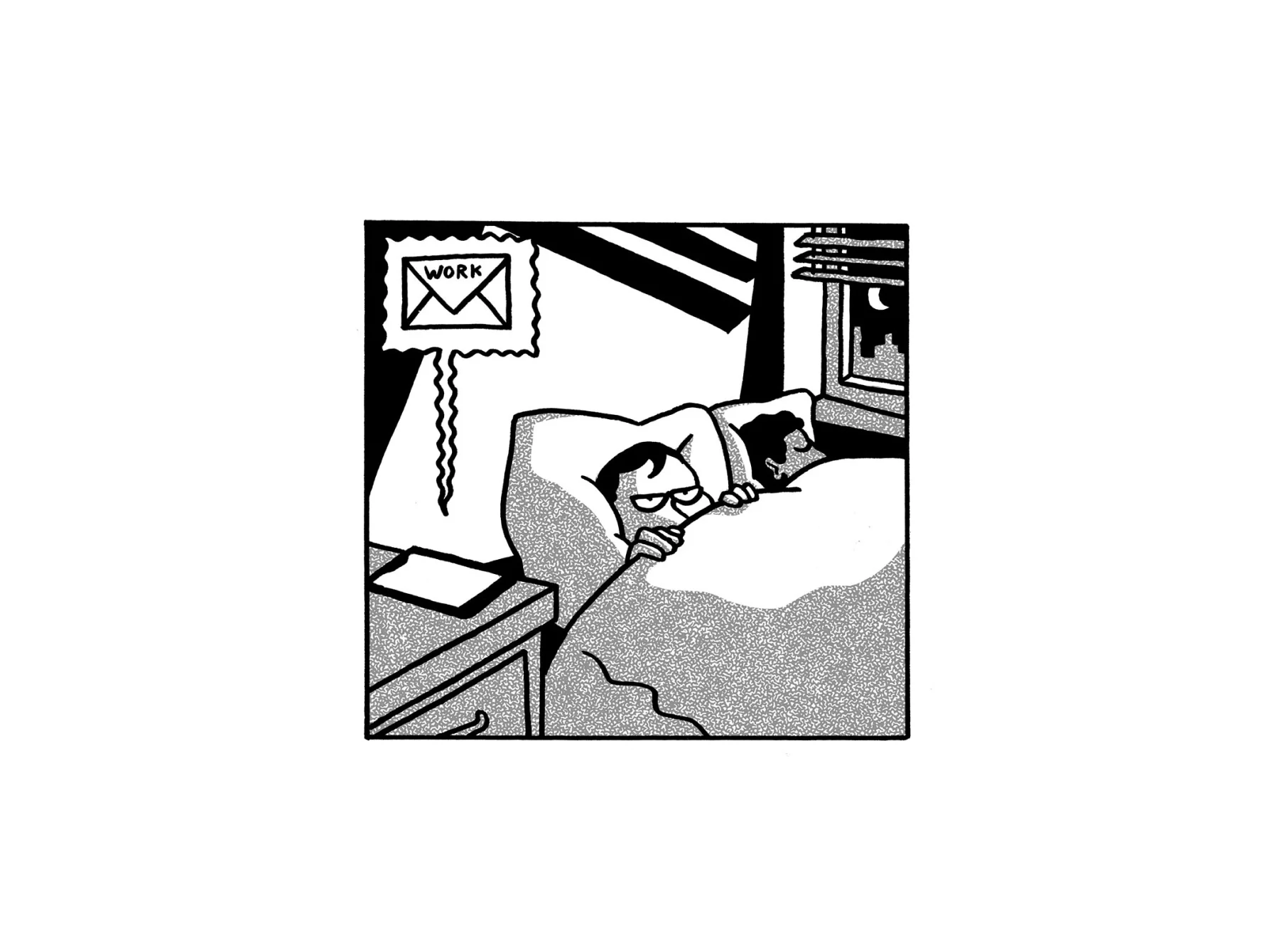

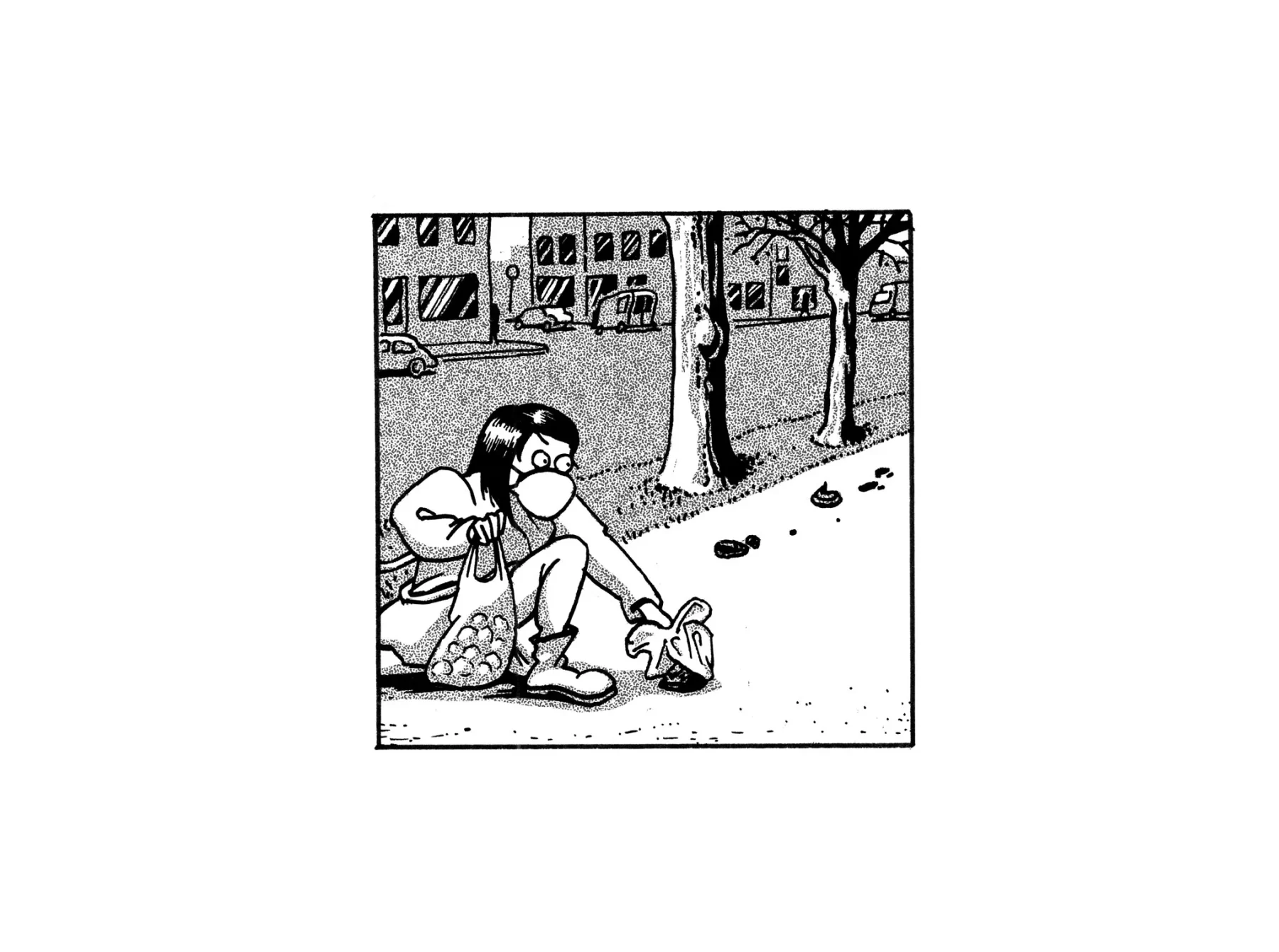

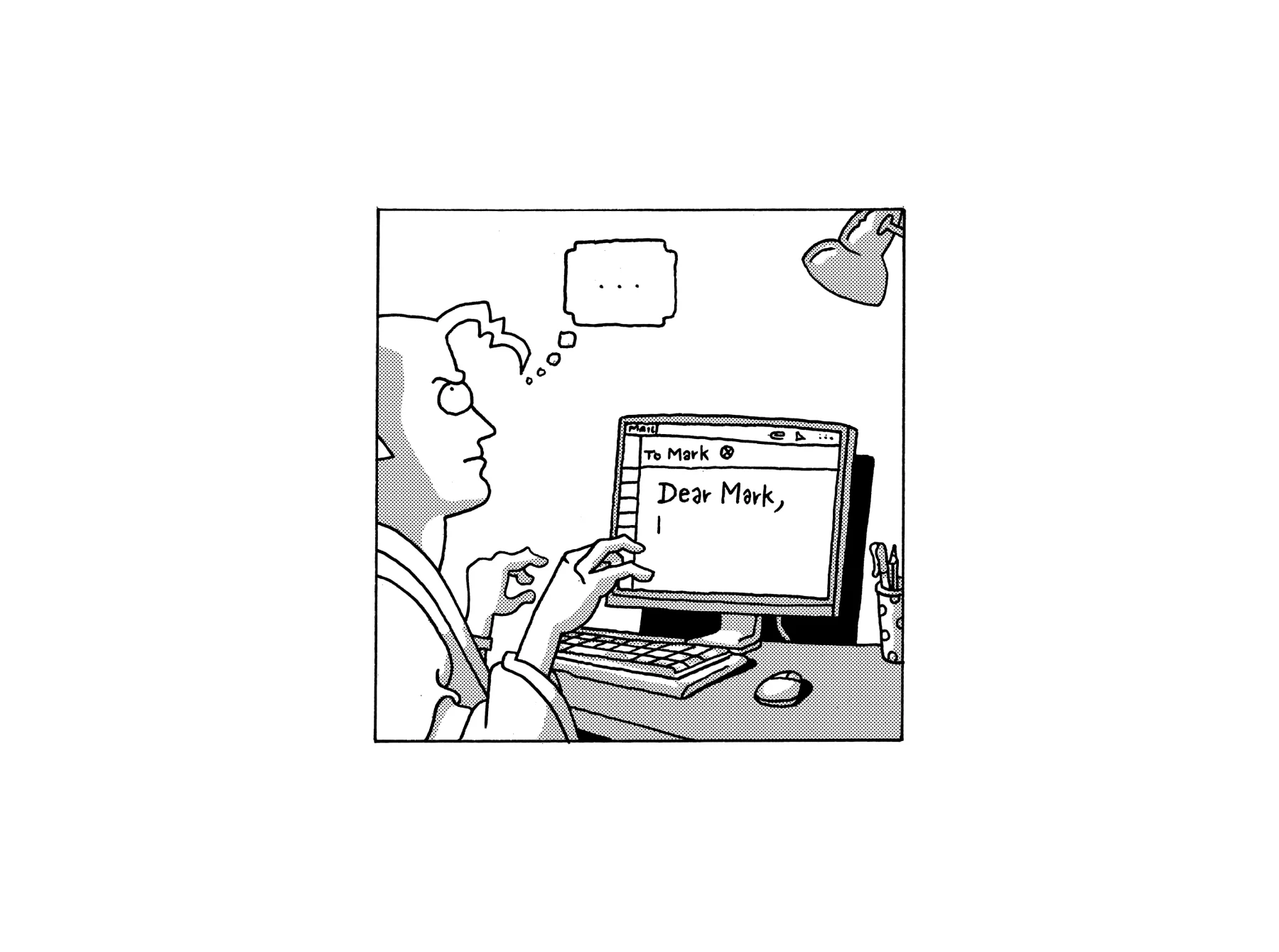

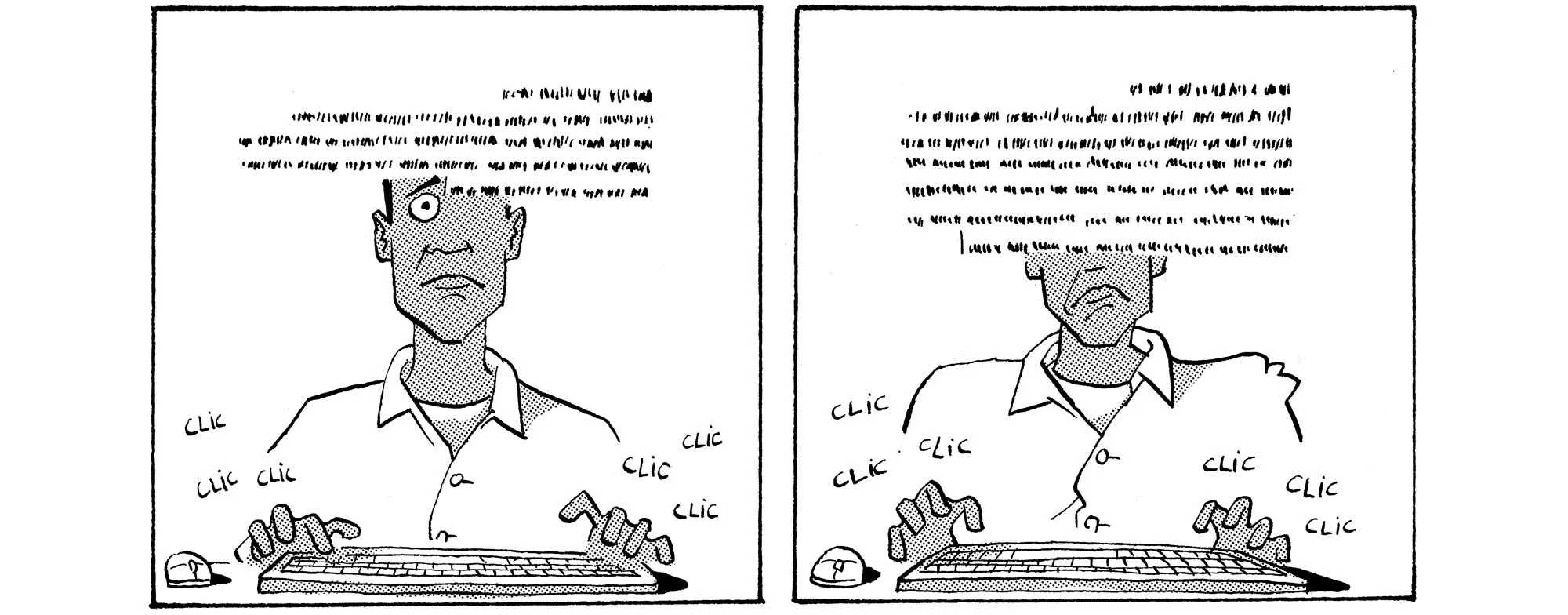

Comic by Baptiste Virot.

“Another ‘race issues’ piece, is it?”

A text pings from my older brother. We had been chatting about work, and I’d just sent him an article I’d recently written about a celebrity’s experience of colourism.

“Yep,” I type back. “An Ammar Kalia special.”

For the past five years, I have been working as a journalist. I had been freelancing previously, but in 2017 I got my proper start as the recipient of a bursary for people of color for a major newspaper. Ever since, my indoctrination into the strange world of the UK media has been defined by what I look like.

Tentatively stepping into the open-plan office space of humming printers and hushed phone calls, editors would ask me: “What do you want to write about?” “Music” would be my typical response—jazz in particular—which would usually get a raised eyebrow in reply. Print media is dying and I’d need to find something less niche than jazz writing to sustain me on this sinking ship.

Editors took every opportunity to remind me that I am a brown man by virtue of the pieces they thought I would have innate knowledge of—a feature on an exhibition about Tantra, a piece on British Asian radio.

Fine, I could be flexible. Getting paid to sit and type about anything already felt like cheating at life. No need to serve cocktails out of a carton to half-cut hen dos? No cold-calling lonely people to convince them to donate their cash? Sign me up.

I knew if I wanted to make a career as a writer, I needed bylines. I had to pitch and I had to say yes to any stories that came my way, all for those precious column inches. As the months rolled on, editors began assigning me pieces: talking to a footballer about his experiences of racism, going to a police briefing about a possibly gang-affiliated stabbing, talking to the inhabitants of a northern town about incidences of Islamophobia, talking to Black country singers about their experiences of—you guessed it—racism. The “race issue” words were flowing out of me.

I had experienced my fair share of racism growing up in London, but I didn’t think having slurs shouted at me from across the street would make me an expert on the topic. In fact, I had never really engaged with my racial background unless someone decided to other me for it. I began to realize now that my role in journalism was being increasingly defined by my perceived “otherness.” Editors took every opportunity to remind me that I am a brown man by virtue of the pieces they thought I would have innate knowledge of—a feature on an exhibition about Tantra, a piece on British Asian radio, a review of a play about partition.

Except, I wasn’t really raised to be brown in the ways that these editors saw me. My parents are first-generation East African Indian immigrants, and when they arrived in England in the 1960s, they faced so much overt racism that they were forced to try and assimilate into dominant, white culture as quickly as they could. That pressure to assimilate was passed on to me and my brother. There was no time to investigate our own background, we were told. Instead, we had to keep our heads down, work hard, and hopefully we’d pass through our lives unnoticed and untroubled.

I did what the other white kids around me did. I listened to Linkin Park and the Offspring, I watched Eastenders and read NME. I only visited India once, when I was seven, and got food poisoning. Now that I had a platform to be read by thousands of people around the world, I found myself representative of a group I knew little about. I was wilfully naive, still stuck in the assumption that I could get by on the force of my merits and ultimately write for who I thought I was, not who editors might have wanted me to be. Yet, I needed to eat, and rather than admit my concerns and be exposed as the fraud I was beginning to think I was, I kept on the treadmill of writing this perceived identity of mine—saying yes to the same pieces that came my way because I didn’t want to be seen as someone who says no.

I was wilfully naive, stuck in the assumption that I could write for who I thought I was, not who editors might have wanted me to be.

One December, I said yes to an unusual piece. I was asked to contribute to a series of personal essays about memorable Christmases. It was the first time I’d been given the freedom to actually write about myself. I was stumped on what to explore, until I eventually settled on the only Christmas that’s seared into my memory: the first one my family had after my mum died in 2013.

It all came quickly and with a surprising ease. I wrote about bereavement and friendship, and the ways we can still learn to find joy even in our saddest moments. When I sent it to my editor, it felt like a weight had been lifted, and when it was published, it garnered a response like nothing I’d written before. Mothers who had been diagnosed with terminal illnesses messaged me to say that the piece had helped reassure them about their children’s futures; people who had lost their parents said they felt seen.

In expressing the emotions of my experience, I finally managed to convey a sense of authenticity about who I was. I was cautious not to make a career out of exposing my traumas, but I realized that if I could publish something so personal, I could also be brave enough to say no to the other pieces that didn’t reflect me. There would be someone else who might be better suited to tell those stories, and I should make space for them instead.

If I could publish something so personal, I could also be brave enough to say no to the other pieces that didn’t reflect me.

Today, I still get commissioned to cover people who look like me, but I’m more comfortable in turning editors down. It has resulted in making the decision to go freelance again, to garner a greater freedom in what I can write about. So far, I’m still making a living.

If we want a fair media landscape—one that isn’t overwhelmingly white and privately-educated—we need our editors to stop tokenizing writers based on their appearance, and to take a chance on new voices with differing backgrounds and perspectives. We as writers also need to interrogate what’s being asked of us, and consider what we can actually best provide.

Our identities are complicated. When we are given the space to explore them authentically, we foster a greater sensitivity and empathy that draws our interviewees and readers in, or that challenges their perceptions.

Where I used to shy away from the first-person, my “I” is in many more of my pieces now. “Race issues,” it turns out, are a beat that I am privileged to work on, and one that I am still exploring as I evolve in myself. The best work comes from being allowed to experiment, and while we do, we can always rely on the piss-taking of our siblings to keep us grounded too.