The barrier between work and leisure has slowly fizzled away, leaving us at the mercy of clients and co-workers who feel it’s okay to contact us at any time of day, any day of the year. Writer Stuart Heritage wonders if this is okay, and explores his own relationship to being “on call.”

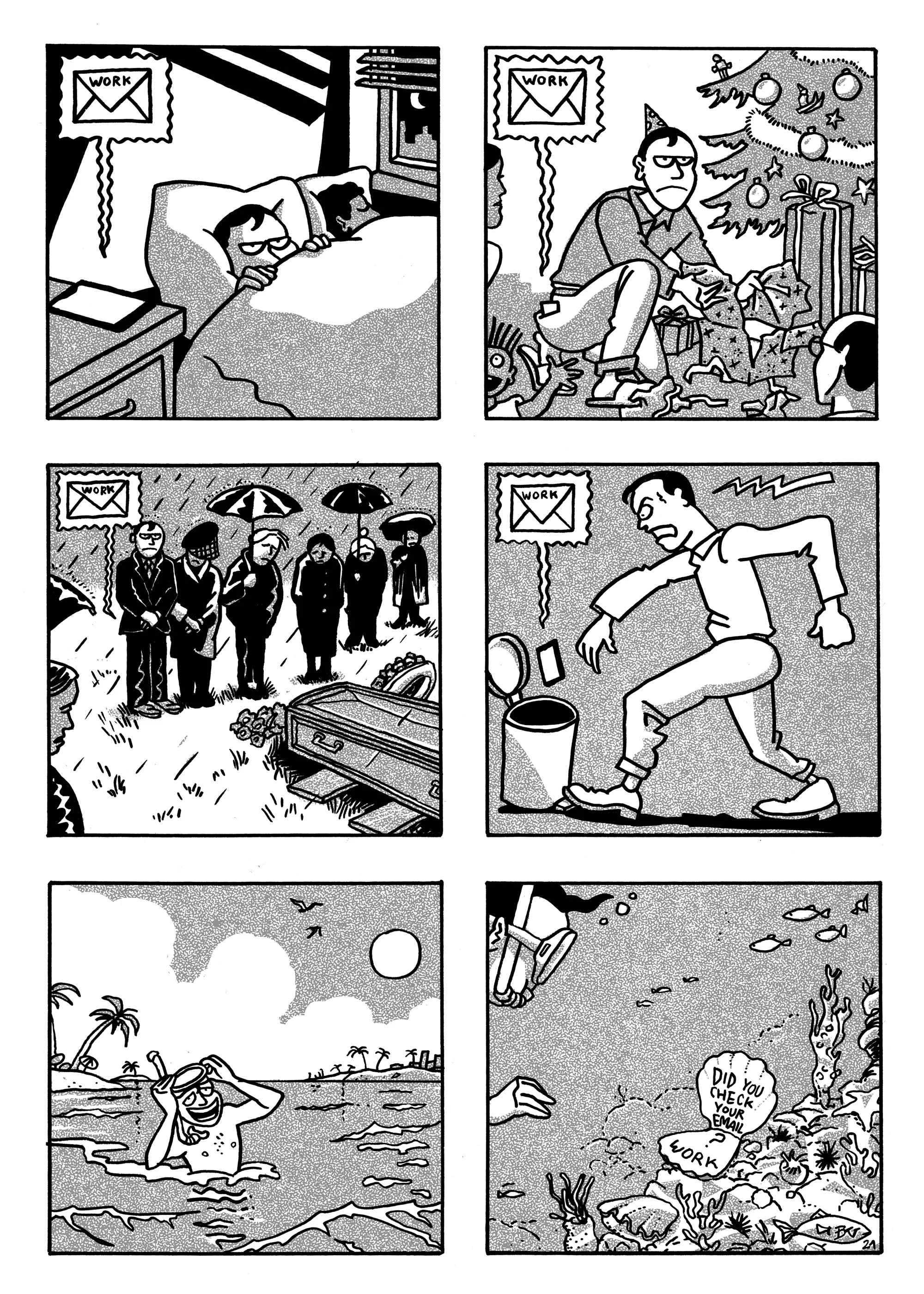

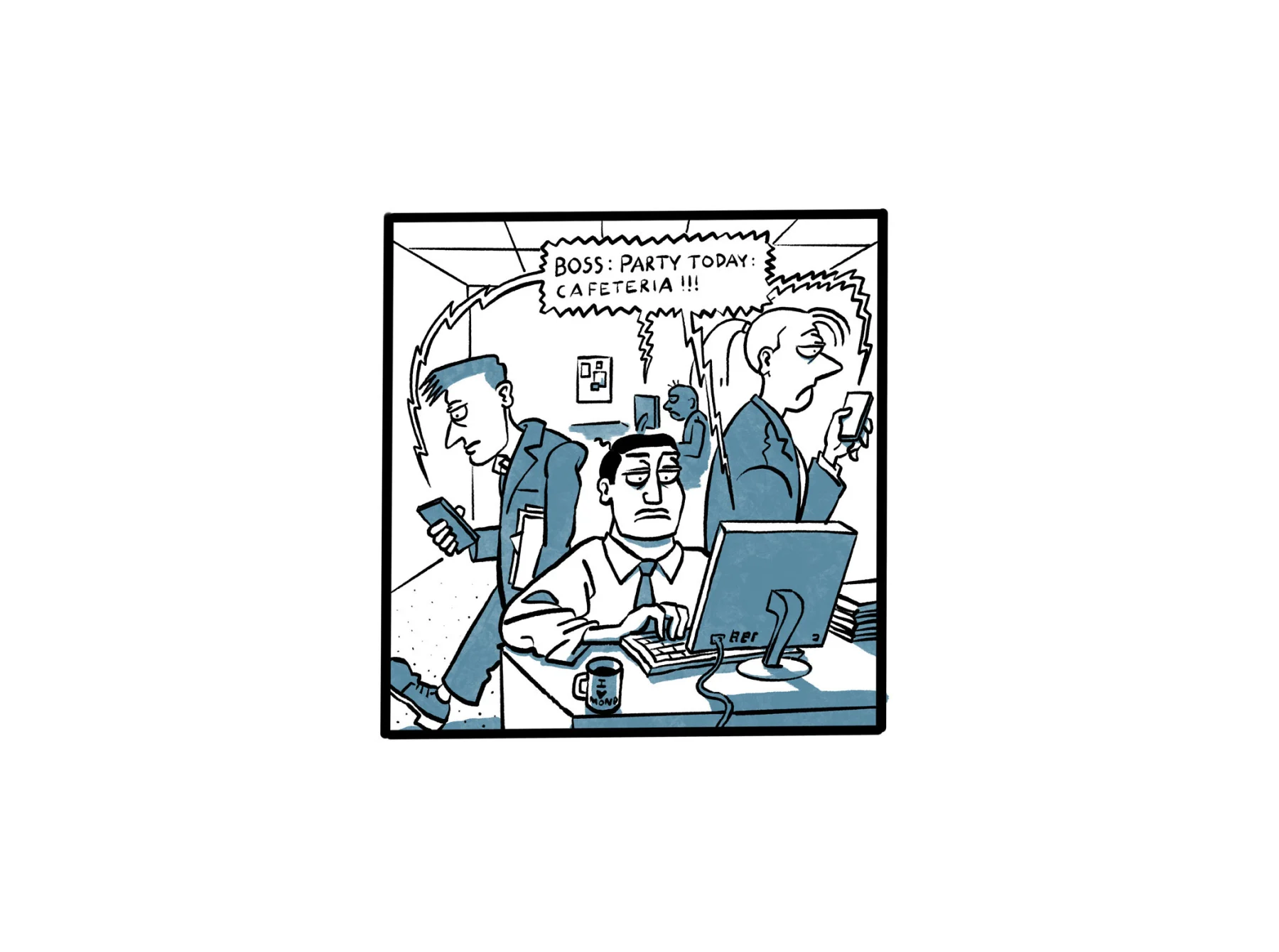

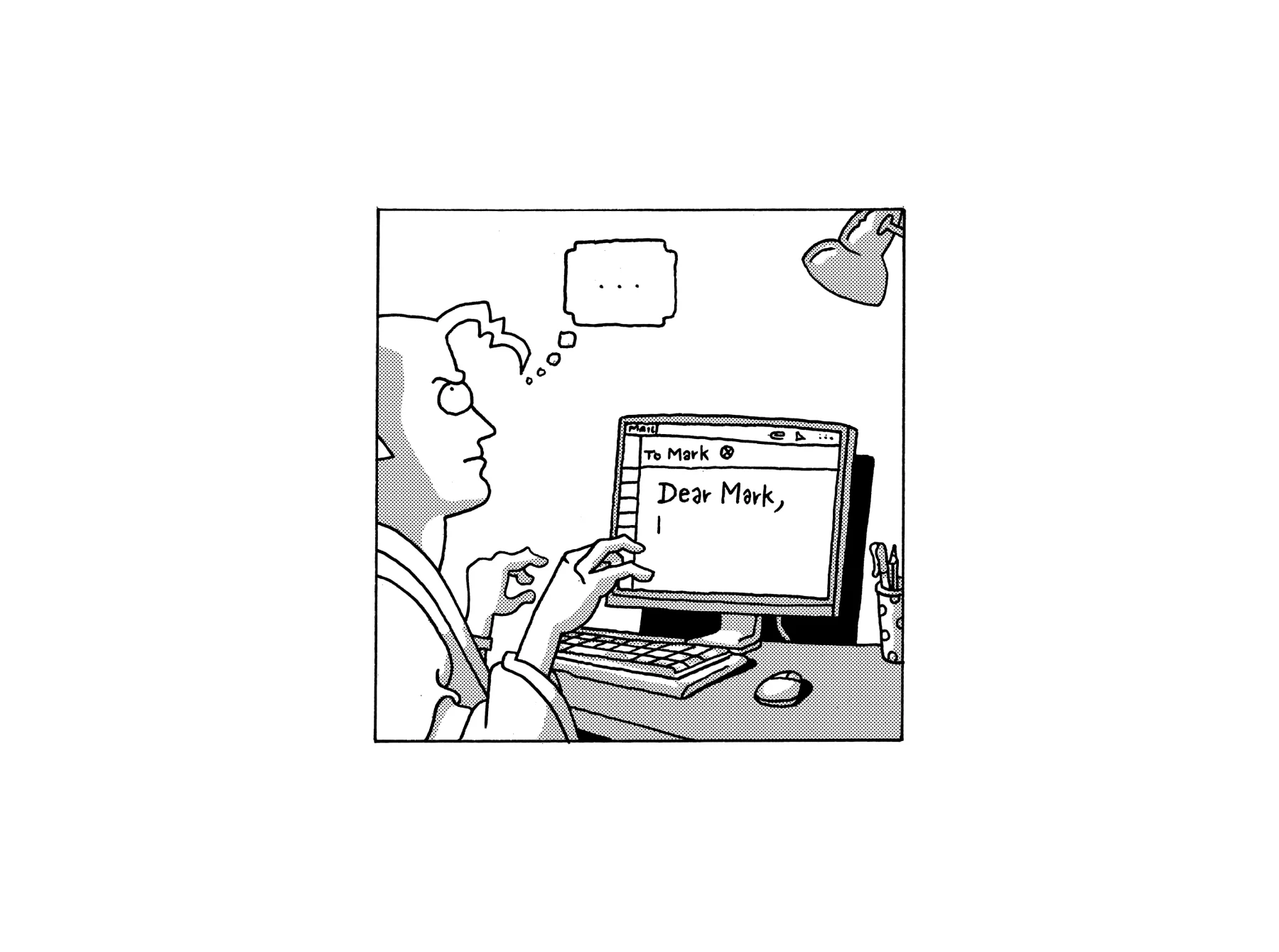

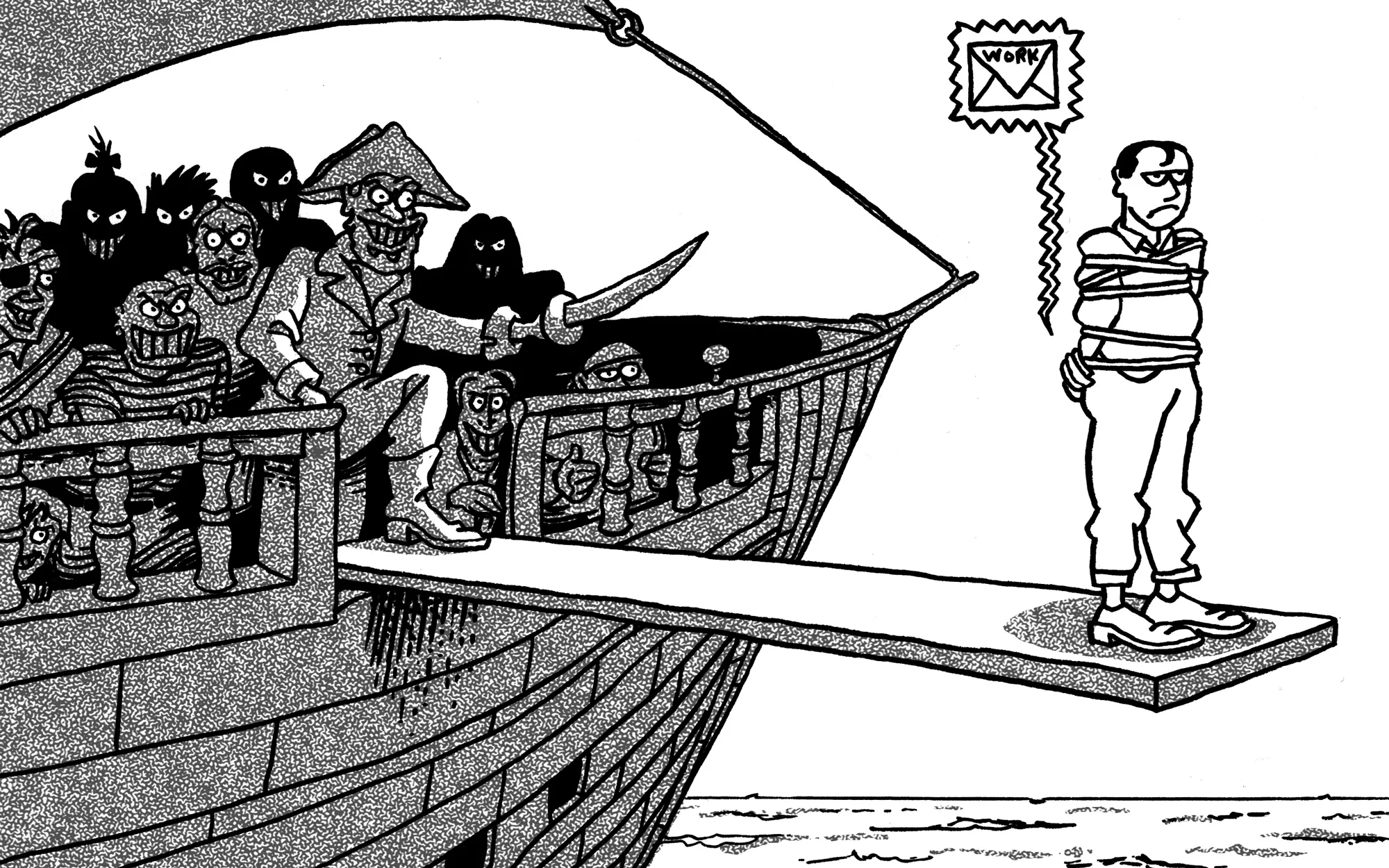

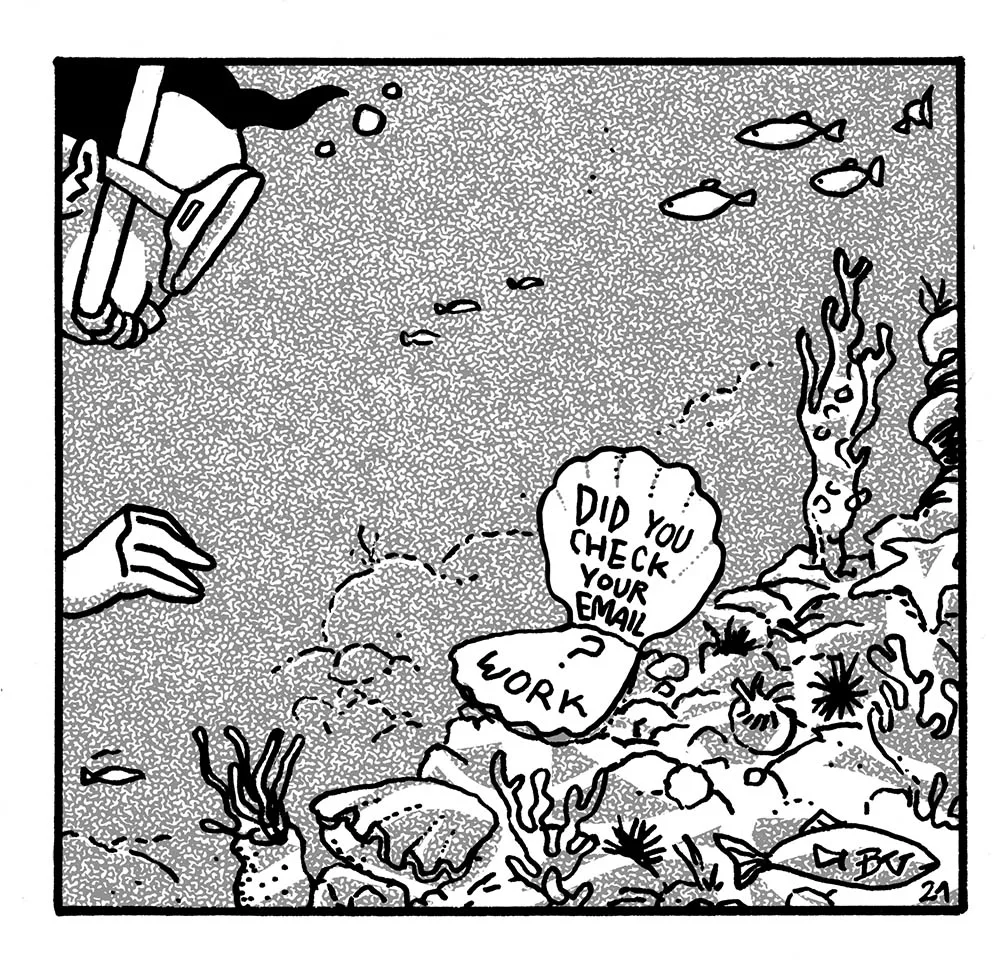

Comic by Baptiste Virot

I might be 40 years old, but I did not become a man until eight years ago. I can tell you the precise day and time that it happened, and I will in a moment, but first let me explain how it happened.

The moment came as I received an email from an editor. “Hi Stuart,” it began. “I’ve just seen that Justin Bieber is planning to retire from music. Could you do me a quick 700 words on all the funny jobs he could do instead of singing, for later this morning?”

Reader, I declined. And the reason I declined was the email’s sign-off. It read:

“PS Merry Christmas.”

Because it was sent on Christmas Day. My editor was asking me to write something about imaginary potential Bieber jobs at nine o’clock in the morning on Christmas Day. I read the email on my phone at my parents’ house, sitting underneath the Christmas tree, unwrapping presents in my pyjamas. And the worst thing is, I considered it. I actually took time to weigh up all the possible repercussions of turning down a commission, instead of screaming “IT’S CHRISTMAS DAY YOU ABSOLUTE FUCKING SOCIOPATH, SHUT UP ABOUT JUSTIN BIEBER” straight back at him.

This is the plague of the modern age. We are always connected. We’re at work when we’re at work, but we’re just as at work when we’re at home. Our bosses know that we have phones, and they know that we check them 150 times a day, and they know that we’re unlikely to refuse a brief out of hours request in order to stay in their good books. And so, little by little, the barrier between work and home has fizzled away into nothing.

The pandemic, obviously, has made this much worse. People who usually work in an office have found themselves lingering in the grey, soupy morass of the work-from-homer, and people who usually work from home have suddenly had to cram all of their work commitments into the gaps between homeschooling. I am in the latter camp. This week alone I’ve found myself answering work emails at 8pm, responding to legal queries at 9pm and making notes for a newspaper feature with a five-year-old asleep on my arm. I even managed to have a catch-up with a book editor, in bed, via the medium of Instagram DMs; an act that until relatively recently would have come with a slightly distressing “U up?” quality.

Little by little, the barrier between work and home has fizzled away into nothing.

And this is me when I’m trying to maintain a boundary between work and home. In the early days of my career, I was pathologically unable to turn off, accepting every single offer of work as soon as it came in. Once I was on a Eurostar, heading for a weekend in France. Somewhere in the Kent countryside I received a message from work asking if I’d like to fill-in for a big-name columnist. When we entered the tunnel and the signal went dead, I composed a long, panicky email explaining that although I was going on holiday, I would nevertheless shelve all my plans, run to whichever internet cafe happened to be closest to Gare du Nord and spend the evening hammering out a column. By the time we popped out in France, I received a reply saying that they’d found someone else.

Which would have been a happy ending, save for the fact that I had to live with the fact I was, momentarily, fully prepared to ditch my entire holiday to work. Why? Because I was convinced that, in the weekly meeting of all commissioning editors from every publication that only exists in my head, my name would be brought up, and it would be revealed that I had the temerity to go on holiday when I could have been working, and everyone would shake their head sadly, and I would be blacklisted.

Our bosses know that we have phones, and they know that we check them 150 times a day.

Clearly, that isn’t the case. In truth my bosses were completely fine with my absence and, the next time the columnist was unavailable, they asked me again. But some professions revel in this psychopathic level of connectivity. Every few months a job listing will go viral for its pure villainy. Last year a “large celebrity” was looking for an assistant. The role, which has hopefully never been filled, required the applicant to “answer your phone/be on call almost 24/7.” They had to wake the celebrity with coffee every morning, have “minimal days off” and “must be willing to travel anywhere at any time.”

Which is deranged, obviously; it’s a hideous, Apprentice-era manifestation of the myth that links constant toil with productivity. And that isn’t the case at all. People need to be able to adequately differentiate between working and not working. This never used to be such a widespread problem. You don’t have to travel too far back to discover a time when a work day had clearly defined parameters. You’d go to your office for 9am, do your work on a typewriter and then, at 5:30pm, stand up, walk out and remain ultimately uncontactable until you stepped back into the office the following morning.

Some professions revel in this psychopathic level of connectivity.

More and more, this seems like the most sensible way to go. Last year, the University of Illinois conducted a study that found that employees who could successfully create boundary control between their work and personal lives were better equipped to create a “stress buffer,” preventing them from adverse effects like negative work rumination and insomnia. These buffers were created by switching their email notifications off, and being firm with their colleagues about when they would realistically reply to messages.

It’s worth doing. The professor from the Illinois study has previously stated that cleaving out some actual, honest-to-God rest time every day would actually make you better at your job. “Employees who unwind from work stress during off-work times are better at showing proactive behaviours to solve problems and are more engaged in their work,” she said.

But this is easier said than done, especially under lockdown. My favored way of deflecting out of hours work messages has always been to lie about my circumstances – “Sorry! I’m on a train!” “Sorry! I don’t have good signal here!” “Sorry! I’m recovering from root canal surgery!” – which of course is almost completely impossible to do at the moment. Obviously I’m not doing anything else. Obviously I’m at home, idly checking my phone every 30 seconds, like everyone in the world has been doing for almost a year.

Obviously I’m at home, idly checking my phone every 30 seconds, like everyone in the world has been doing for almost a year.

However, let’s be optimistic. If I can’t lie, then the least I can do is treat lockdown as a learning experience. So now I’m experimenting with something quite dangerous: the truth. Now, if I don’t want to work outside of work hours, my only option is to baldly state: “Sorry, I don’t want to work outside of work hours.” No explanation. No fear of repercussions. And it works, too. It turns out that, as soon as you lay down some sensible ground rules, most sensible bosses will respect them.

Telling the truth is actually quite liberating. Still stung by Biebergate, my end of year Out of Office last year was starker than it has ever been. “You and I both know I’ve read your email,” it said. “But it’s Christmas, so don’t expect a reply.”