In her early twenties, writer and comedian Monica Heisey dreamed of the day she would cast off her waitressing aprons and bargain-bin blazers, and dress as her true self at work. But moving through TV writers’ rooms and publishing parties, where the lines between personal and professional identities are blurred, she’s discovered there are unexpected benefits to the workplace uniform.

I have never quite known how to dress for work. Just as my parents’ sense of how to acquire a job (“Go out and knock on some doors,” or “Get a bachelor’s degree”) was outdated by the time I entered the workforce, so too was their fashion advice. But before I figured that out, I spent my university summers handing out résumés, sweating in a cheap blazer Mum and Dad thought “looked professional,” and waitressing in various itchy polo shirts or hyper-starched aprons.

My first office jobs were when things went truly off the rails: without any sense of what office workers wore, I adopted a kind of Joan Holloway drag, stuffing myself into pencil skirts and little cardigans, looking somehow both 55 and like an extra in a high school production of “Guys and Dolls.”

Uniforms, formal and informal, have long served an important symbolic and practical function. A chef’s whites can be easily bleached, but their crisp brightness also conveys elegance and control. Army fatigues are hard-wearing, can provide camouflage, and, crucially, let you know which guys are your guys, and which are the enemy. While not a uniform per se, TikTok girls putting a dab of highlighting blush on their noses before a beauty haul do so to signify that they are Part Of Something. Plus, as Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg or any other technocrat can tell you, sometimes it’s just nice not to have to choose what to wear in the mornings.

I was relieved to be free of my years of uniforms: finally, a job where I didn’t have to dress as anyone but myself.

In my early twenties (and in the absence of Facebook or Apple money), I felt the opposite. When I eventually started working as a writer and sometimes comedian, I was relieved to be free of my years of uniforms: finally, a job where I didn’t have to dress as anyone but myself. I loved that I could work from home all day, or write in cafés nursing one green tea for seven hours, wearing whatever I liked, which at that time was mostly American Apparel short shorts, vintage bathing suits, and anything with a Peter Pan collar. What a thrill, I thought, to be unencumbered by a professional dress code (or its more opaque sibling “business casual”). I was doing my own thing, no rules about slacks or open-toed shoes holding me back. No more polyester waitressing uniforms, no more trawling the J. Crew sale for sad trousers in shades of greige and tan. I was truly free.

It took a few years for me to realize that this was bullshit. At first I only noticed trends. At media or publishing parties I encountered a sea of black outfits, canvas tote bags, and severe fringes. At stand-up nights, plaid button-downs seemed to have been distributed to performers in advance. In television writing rooms, people wore free T-shirts from improv festivals and got a bit intense about sneakers. It felt more casual than a dress code, but was still enforced in its own way.

My job was supposed to be cool and laid-back! I had a boss who wore cut-offs! What was the point in working nearly all of the time if I couldn’t dress like myself while I did it?

Once, at the beginning of a TV job, I asked a more experienced writer for advice on fitting into male-dominated comedy rooms. “If you want to wear lipstick at any point, make sure you wear it on the first day,” she said. “Otherwise, the first time you come in with lipstick on will be a whole thing.” She was right. Once, on a sitcom, our head writer showed up wearing tracksuit bottoms instead of his usual professional attire after a gym mishap. It caused such a stir we had to break early for lunch, and we called him “Sweatpants” for the rest of the week.

Over the years my own style evolved into something almost cartoonishly “TV writer” in affect: loose jeans or corduroy trousers and a crewneck sweatshirt or vintage T-shirt, preferably with an ironic slogan (”Women Want Me, Fish Fear me,” “99% Devil 1% Angel”—you get it), finished with a backpack and a pair of big, comfy sneakers. I wouldn’t have been caught dead in lipstick at work, though my personal style just a few years prior could best have been described as “time traveler from 1950 gets lost on the set of ‘New Girl.’” One day, while pulling on yet another slogan tee to go with my Asics and 501s, I realized: I had a uniform, too. It wasn’t the blazer and trousers of my office-attending peers, but it was still an outfit defined by my work, something to mark me as part of—and help me blend in with—a particular professional community.

I was horrified by this. My job was supposed to be cool and laid-back! I had a boss who wore cut-offs! What was the point in working nearly all of the time if I couldn’t dress like myself while I did it?

In truth, I had been wearing the tea dresses less often in my off-hours, too—the TV writer costume had mostly taken over.

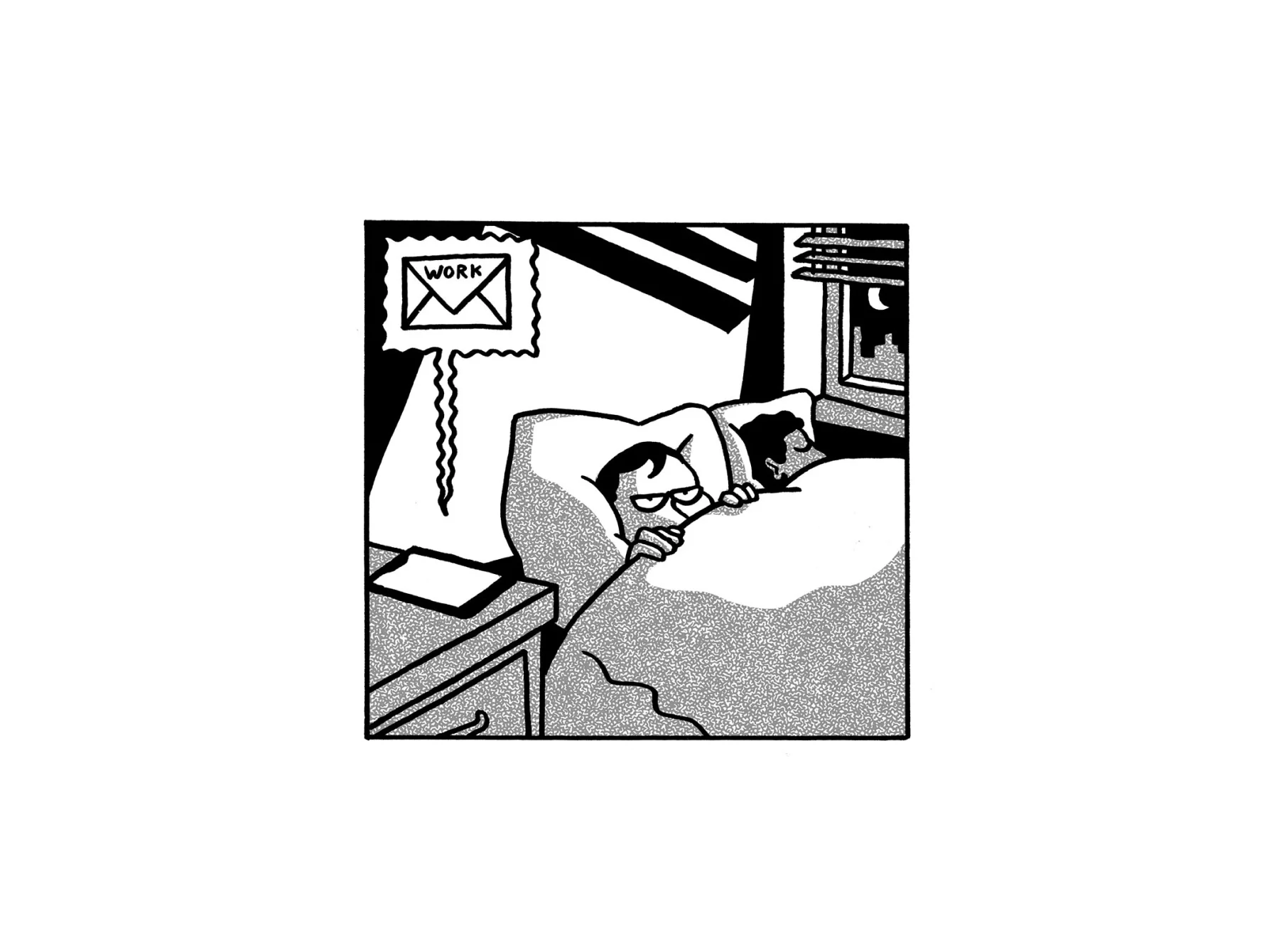

I imagined wearing one of my twee little tea dresses into work, and vetoed it instantly. It was asking for a Sweatpants situation. In truth, I had been wearing the tea dresses less often in my off-hours, too—the TV writer costume had mostly taken over, sartorial evidence of the slow creep of my professional life into every other aspect of my days and, increasingly, nights. Much like the outfit—painstakingly chosen items meant to create a sense of ironic effortlessness—the idea of the industry had been a lie. This isn’t a casual job, whether or not I could do it from a coffee shop, from home, or anywhere else. It was an incredibly competitive industry that required those of us at entry level to work nearly constantly for minimal to moderate pay. Being able to wear slippers while I did it didn’t mean my work was relaxing; it meant that work could creep into any moment of my life, even the time I was meant to be putting my feet up, winding down, or taking a moment for myself.

These days I like the idea of having a work uniform, something I can put on to switch into professional gear and take off when I’m ready to relax. As work creeps its way into our off-hours via email and remote working, there’s something nice about a visual marker of the version of myself who’s interested in leisure, who doesn’t have anywhere to be at 9am, who certainly is not answering a Zoom after five. It’s equally nice to feel suited up for work, to show up somewhere looking the part, do the job, and go home.

The best part of a work uniform, after all, is taking it off at the end of the day.