Quitting gets a bad rep. As children, we’re constantly told that it is an act to be avoided. To be a “quitter” just won’t do. Only later in life does the penny slowly drop and you realise that quitting isn’t just about wimping out or a can’t-be-bothered attitude. It’s about taking control of the situations, people and relationships that can forge – or damage – the meandering path of your life. Writer Ruby Tandoh is a prolific, self-professed quitter, and proud of it. As part of our Work Sucks, I Know series in which writers explore how jobs aren’t all they’re cracked up to be, she explains why.

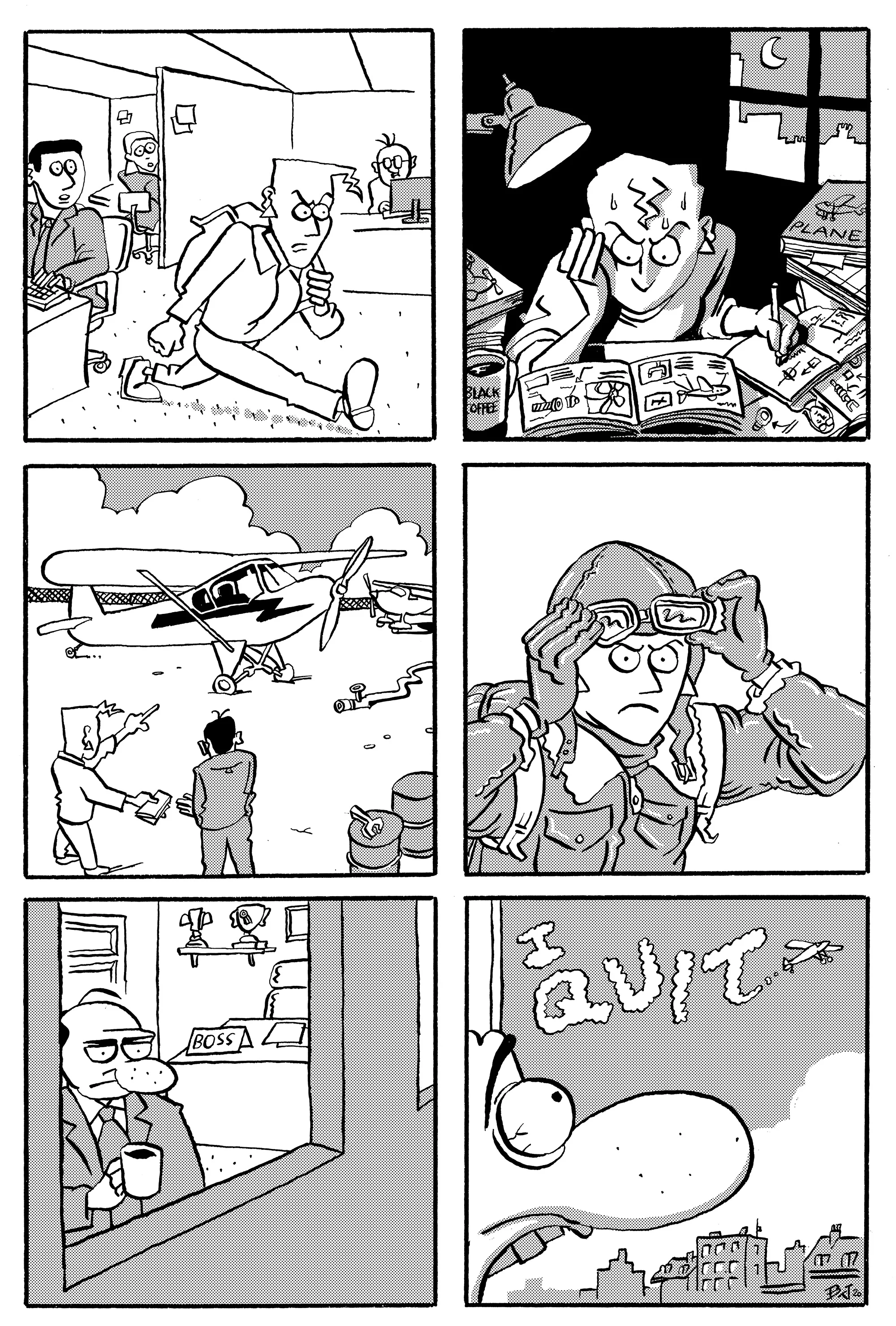

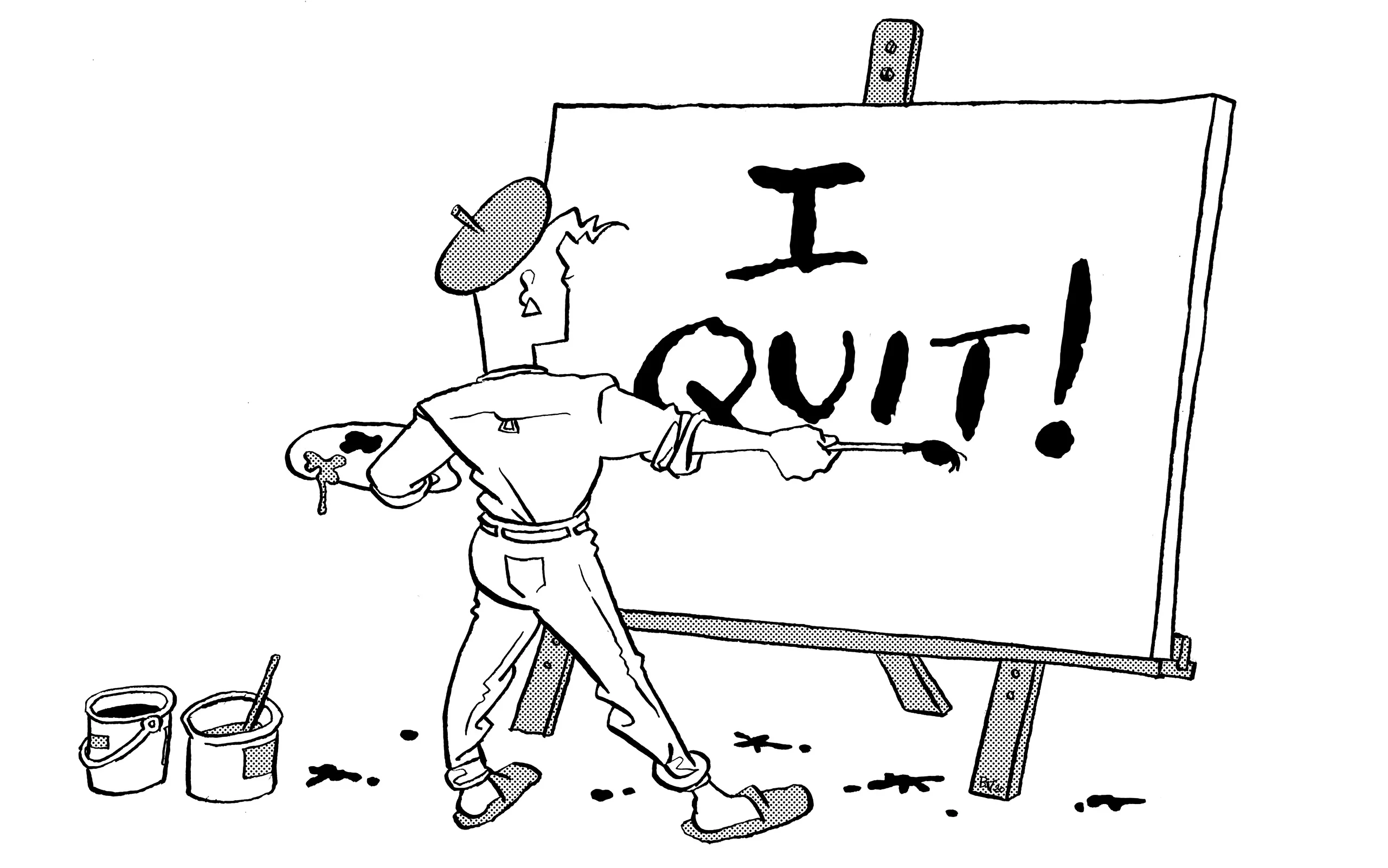

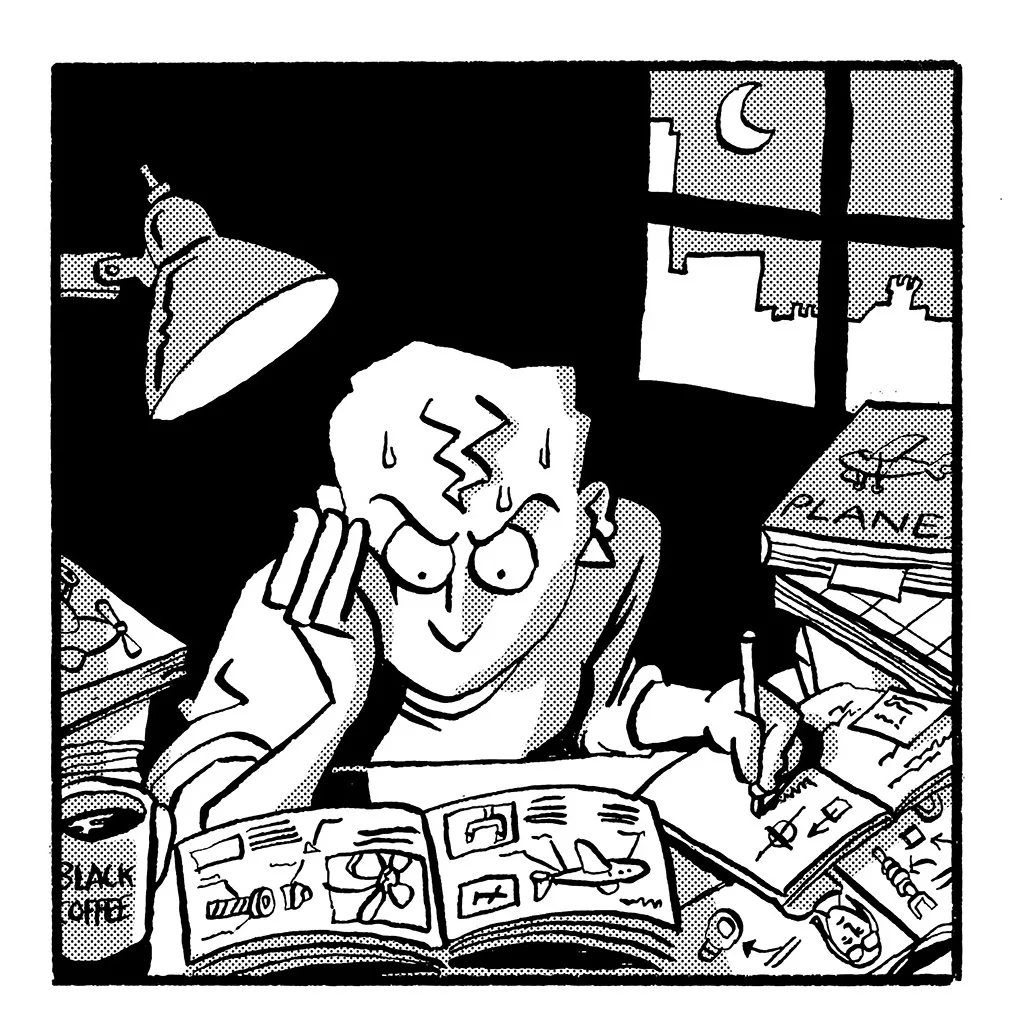

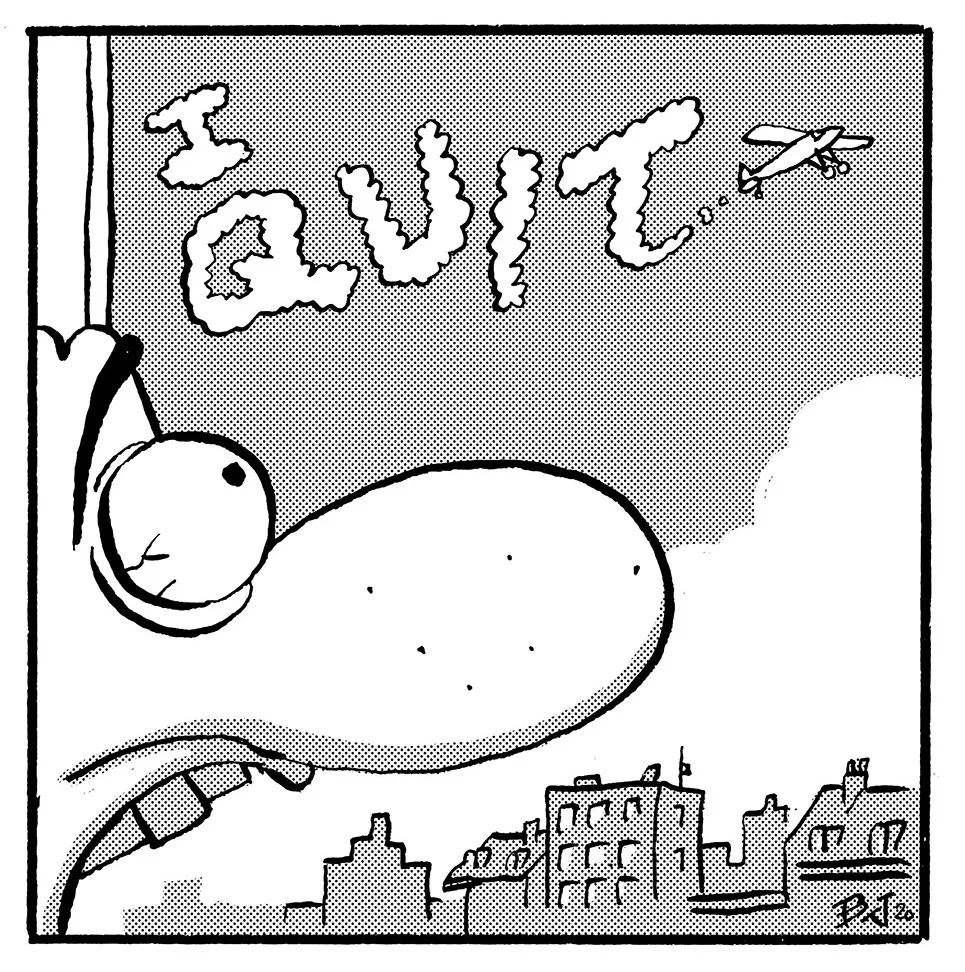

Comic by Baptiste Virot

There is an art to quitting. Anyone can quit – just unplug, pick up and walk away – but it takes a level of mastery to quit well. My definition of quitting well is, as it happens, more or less exactly the same as most people’s definition of quitting badly. It is upping and leaving before you’ve had a chance to lay down roots. It is extravagantly burning your bridges and changing your entire life course with less deliberation than most people give to changing their broadband contract. It is explosive, reckless quitting, just as you approach the apex of the curve. This quitting is the feeling in your stomach when your car flies over the crest of the bridge: a jolt that separates you from yourself. In that moment, you feel weightless.

I’m an evangelist for this kind of quitting. Ever a bad influence, I advise people to quit far more enthusiastically than I ever impel them to stay. It is something like the “dump him” refrain of faceless internet friends: an easy remedy for a systemic wrong; making islands of people to save them from hurt. Why sit steady, I will ask, when you could spin a new story for yourself? A career change sparkles on the horizon. A dazzling romance beckons. The only thing more thrilling than quitting something is starting something new. In the vacuum that quitting creates, countless new maybes rush in.

In my defence, and perhaps to my detriment, I practise what I preach. When I was 18, just days before I was due to start a physics degree at a university I’d always dreamed of attending, I quit. That was back when I wanted to be a meteorologist, fresh off the back of one too many viewings of The Day After Tomorrow. I went back to sixth form and took an art A level and applied to art schools instead. Before that had a chance to fail, I quit. Next was the last-minute switch to a philosophy degree in London. Within weeks of starting, I’d switched degree programme. Within the year, I had quit. There were two faltering years of another degree at another university. And then I quit. Most recently there was a creative writing course, which, naturally, I quit. I considered quitting this article about quitting, twice.

At every point, the reasons to quit felt compelling. First, there was a breakdown that sent me, briefly, to a psychiatric inpatient ward. There were breakups and bad teachers, an eating disorder and the insidious voice of my poor self-esteem. An ill-timed comment was impetus enough for me to set out for pastures new; a perceived slight would set in motion a downward spiral from which I could only recover with a decisive full stop, a quit. At the slightest discomfort, an itch would begin to settle in my chest, small at first but soon as insistent as a scream. Quitting felt like breaking through the surface of the water, like breathing again.

A machine never quits: if you can be defiant, you can feel alive.

There has been no area of my life safe from these fickle squalls. I have quit relationships, homes, personalities, religions, friends, holidays, plans, studies and styles, landing every time in the lap of chaos, back at square one. For about 15 minutes when I was in Year 11, I changed my Myspace orientation label to “bisexual.” For many years after, I considered myself straight. I was gay for a while, or so I thought, and announced it to the world on Twitter. I decided that this wasn’t strictly true at more or less the exact moment as I pressed “Send Tweet” and documented this untruth for posterity. Sometimes I wonder whether this is just the lot that we probably-bisexuals have to endure: an erasure of who you think you are depending on whoever you happen to fancy at that moment.

In the small things, my compulsion for new endings and new beginnings reveals itself with particular acuity. There’s nothing I love more than to trim down my possessions to the bare essentials, whittling in trips to the charity shop and to clothes banks until I have a skeleton kit – a life that can be upended at a moment’s notice. This streamlining soothes me nearly as much as the rituals of reinvention that succeed it: the new year, new me; a revised capsule wardrobe; an experiment in A-line skirts, again, even though they have never, will never, suit me.

The physical stuff is only the beginning of it. Online, I quit friends and followers with a single, satisfying click. I quit social media every few weeks, sometimes quietly, sometimes insisting on fanfare, but always with a sense that this time it’s for good. I happily cut myself free of whole sections of my past by deleting all photos, documents, contacts and emails. I delete the contents of my laptop’s recycle bin with what can only be described as relish. “The weather in March is a lot like me,” declares Elizabeth in E. L. Konigsburg’s children’s book Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth. “Nice for one day and then nasty for two.” On up days, I bristle with excitement at the prospect of razing everything to the ground. Other times, I look at my life and wonder where it’s all gone.

I’m not sure how I became like this, so hooked on the shock of the new. Other people’s stories seem to be about progression and improvement: one thing builds on another, the past forms the foundations that hold up a bigger, better present. But mine is a more staccato rhythm, periods of frantic planning and connection and creativity rising to a crescendo until that moment when, yet again, a shock of mounting static, I quit. At least, that’s the way it feels. I’m prone to exaggeration, though, I know. Maybe I should quit that, too.

It has become clear in recent months that this way of living – keeping myself warm with the bridges I burn – isn’t really sustainable. I feel fragmented and exhausted, cobbled together from the wreckage of the things I couldn’t bring myself to finish. But still, there is something in quitting – a grenade thrown into the Twittersphere, a self-righteous letter of resignation, a spectacular blazing row – that I just can’t let go of.

Psychotherapist and relationships expert Esther Perel has described the impulse to say no as a way of preserving something vital of yourself, of your will, in situations where you feel stripped of power. “Opposition becomes autonomy,” she sums it up – I quit, therefore I am. In the world of work, these psychological self-preservation mechanisms take on a particular resonance. At work, unless you are completely self-reliant or at the top of your company, you’re likely to be buffeted by forces greater than you in more or less every facet of your working day: there is a time for work and a time for break; quotas need to be met and workloads managed; uniform is dictated; hours are clocked and progress tracked; holiday is refused or granted; and in the midst of the current crisis, hours are cut and people sacked. When so little is within your control, and especially if you’re not protected by unions or contracts (think of freelancers or the nominally self-employed army of taxi drivers and delivery riders), quitting is the last juncture at which you can shore up your sense of yourself as a real, living, dreaming person. A machine never quits: if you can be defiant, you can feel alive.

Quitting felt like breaking through the surface of the water, like breathing again.

At the cinema where I used to work as an usher, quitting meant saying no to the sales quotas and the managers who’d talk loudly about my butt as I walked up the stairs. Years later, I quit my dream job writing recipes for a broadsheet newspaper when it became clear that our food philosophies were at odds. I have quit speaking engagements when I realised that it would tank my already fragile mental wellbeing to go ahead. I quit a kitchen job when the head chef kept getting changed in my pastry room and starting a conversation, like clockwork, the moment that he was stripped down to his boxers.

Of course, not everyone has the luxury of quitting quite so freely. The freedom to quit is a resource spread unevenly across lines of class, gender and race, with the most vulnerable left with little choice but to stay in bad jobs with bad bosses. When you’ve got nothing, quitting isn’t an option. But lots of the best work we do as humans is the stuff that happens in the vast, improbable landscapes of our imaginations. If you can imagine quitting – if you can feel the weight of the pen in your hand as you sign your phantom resignation note, if you can picture slamming the door – you can hold onto some fragment of the defiant, autonomous, asshole you really are. Opposition becomes autonomy, if only in your dreams.

Recently, I’ve been trying to quit less and stay more. I started a job in an ice cream parlour where I learned how to churn ice cream and clean a giant pasteurizer and temper chocolate and make a Jaffa Cake Bombe (every bit as wild and wondrous as it sounds). I worked hard, sometimes loving it, other times hating it, but every morning resisting my natural compulsion to quit. I sat through the restlessness and the fear and showed up each day ready to keep going. And then, just as coronavirus began to dig in its claws, they fired me. For a moment, I was aghast. I thought about torching the place, or about sending my uniform back with “WORKERS RIGHTS” scrawled across the T-shirt in permanent marker. But then I smiled, and then laughed. The day sprawled long and free ahead of me. And for once, I hadn’t quit.