When you’re a kid, it’s natural to assume the job you choose when your school days are over is one you will have until retirement. It’s rarely the case. Most of us hop around a bit in a bid to work out who we really are, what we really want to do, who are our people, where we should be. Some don’t, and they’re called “Lifers.” Here, writer Robert Ito explores the increasingly rare breed of person who picks a job and stays in it for life.

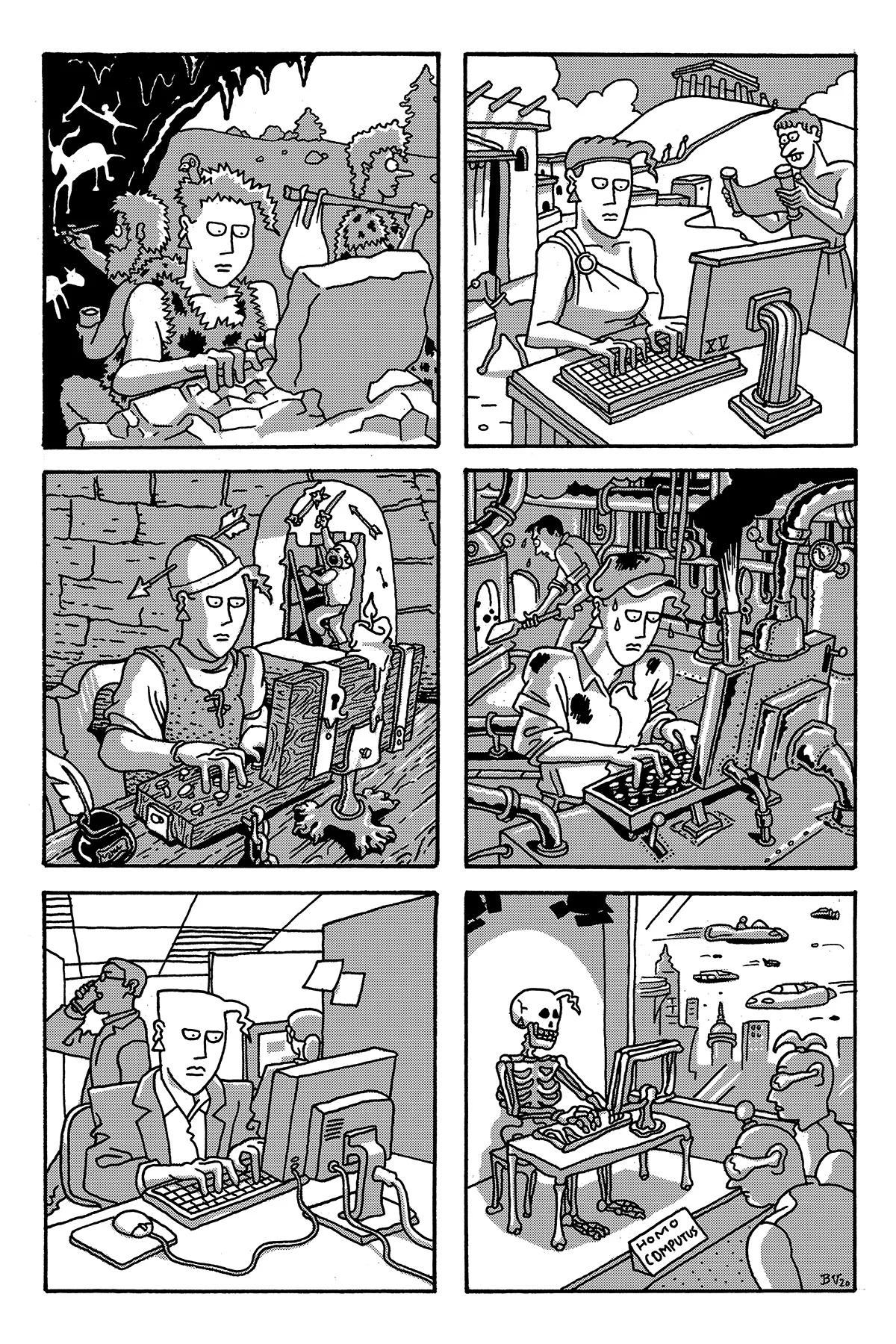

Comic by Baptiste Virot

When I was 17 I joined the marines, in the hopes of playing in one of their bands. I was a decent saxophonist, or so I thought, and it seemed like a good idea at the time; a chance to escape my small rural hometown in California’s Central Valley and see the world. When I got to my first unit, however, nestled in the woods of coastal North Carolina, I found that the musicians there were pretty evenly split between first-termers like myself, who realized early on that this life was not for us, and the officers and sergeants who had made marine bands their career.

Many of these old-timers loved the closeness and camaraderie of the Corps and hated civilians, who they looked down upon as undisciplined losers. Several were alcoholics and at least a few of them suffered from PTSD from their time in combat units, something we would joke about because we were young assholes. We called these guys “lifers.” It was not a compliment. Why would you do one single thing in your life until you were too old to do anything else (in this case, your mid-40s) when there was so much else in the world to do and see and be?

Today, many of us look at the prospect of committing to a single career with a combination of disbelief and condescension. There’s also perhaps not a little envy in the mix, whether one wants to acknowledge it or not. If I had stayed at Company X rather than quitting over that inane argument with my horrible boss, one wonders, would I be some high-paid exec by now? We look at colleagues who stayed and gutted it out, and we question our own stamina and stick-to-itiveness.

Maybe it’s not that lifers are unimaginative and complacent, maybe we’re just lazy! Or impatient, or scared, even. Many of us look at commitment and see only the downside, the prospect of getting stuck in a dead-end job we hate. It doesn’t help that so many of the historical and cultural models of lifer-dom are negative ones, from the man in the gray flannel suit in the ‘50s to the overworked Japanese salaryman of the ‘90s to, what? In the gig economy, is there even a model of the committed lifer now, aspirational or not?

Whether you have one job in your lifetime or a dozen, you’re likely going to have one of those ‘road not taken’ moments.

Indeed, one seems to see fewer and fewer lifers. In the most recent survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. workers have an average of 12 jobs in their lifetime; for workers in the U.S. and U.K, the median stay at any one gig is about four years. In today’s workplace, many of the perks of committing to a single job or company – pensions, cradle-to-grave job security, that gold watch at the end of it all – are increasingly rare. Why would one pledge one’s life and loyalty to a boss who could fire you tomorrow without notice or cause, or to a position that might get eliminated or outsourced next year? Even if one wanted to commit, many of the jobs people used to do until retirement age are in danger of being eliminated by AI (hotel clerks and concierges) or robots (auto plant workers, seamstresses) or self-driving cars (short haul truckers, limo drivers). Not that the gig economy, with its promise of increased flexibility and freedom, is necessarily any better. As Sarah Kessler noted in her otherwise boosterish book Gigged: The End of the Job and the Future of Work, the gig economy “could amplify the same problems that made the world of work look so terrifying in the first place: insecurity, increased risk, lack of stability, and diminishing workers’ rights.”

Despite all this, one still sees lifers here and there. Long after I packed up my saxophone for good, I continue to hear about friends and teachers who never stopped playing: a college bandmate who is now a world class bassoonist, a former music theory instructor, Abdu Salim, who leads a jazz trio in Europe. There are the friends I struggled alongside in grad school who are now tenured professors. Colleagues I knew as an editor at a city magazine are still editors today, even as newsrooms shrank down to skeleton crews and the rest of us went off to work for Planned Parenthood and design studios and assorted nonprofits, or became writers for hire, like myself.

Perhaps you are even working alongside a happy lifer now. What’s it like? Maybe they make you question yourself, because they find such inspiration and joy in things you find humdrum. Maybe they thrill and inspire you enough to try to see work as they see it. Years ago, I helped pay my way through college working as a cook in a Japanese restaurant. The job was tedious, as so many low-level cooking gigs are: cutting up chickens and peeling shrimp and grilling steaks, lots of steaks. To one of my colleagues, however, it was a lifelong passion. Where I saw a waystation, he saw a noble profession. He used to voraciously read Gourmet magazines while the rest of us were doing who knows what, and probably imagined himself working at some fancy place someday, one with linen tablecloths instead of paper ones. The thing was, when I was with him, usually prepping, I felt that I too was part of something grand.

Today, many of us look at the prospect of committing to a single career with a combination of disbelief and condescension.

One finds such people in every place and profession. Years later, I had a colleague at a magazine who spent more than 10 years writing a true-crime book; he confided to us once that he had long ago stopped making money on the endeavor, and that he would have made more money over the same period of time working as a barista at Starbucks. So why did he do it? Because he loved everything about that damn story, from the tale itself and the research it took to uncover it, to the telling of it, page after revealing page.

Maybe you’re a lifer like him, or on your way to becoming one. If so, good for you! You might be your organization’s institutional memory, the old pro, the one who knows what’s worked before, and what’s flamed out miserably. Hopefully you’re a mentor, too, one who inspires other workers rather than talks down to them. In Good People: The Only Leadership Decision that Really Matters, Anthony Tjan describes mentors as people who are not only good teachers, they’re good, period. Mentors, he says, “help others succeed in a world that so often pressures us to be people we don’t want to be and to do things we don’t want to do.” If you’re a lifer, be that lifer.

Of course, the easiest way to have that sort of commitment is to find something you really enjoy doing. If you find a job you love, that old, corny saying goes, you’ll never work a day in your life, and the line makes a lot of sense. The trick, of course, is making love stay. Anyone can love coding, say, or fixing cars, if you only have to do it for a year. How are you liking things in year two, or three, or 30? The lucky ones who are still able to love their jobs after a lifetime are probably finding ways to keep things fresh.

Whether you have one job in your lifetime or a dozen, though, you’re likely going to have one of those “road not taken” moments, if not tomorrow, then someday. I met up with a marine friend a few years back, and we started talking about the old days. From what I knew about his situation, he had had a tougher go of things than I had. He married young, while in the service, and was assigned to one of the worst duty stations and bands in the corps: playing recruit graduation ceremonies at Parris Island, South Carolina, the infamous marine boot camp immortalized in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket.

In 1956, a drill instructor there got drunk and marched his platoon into a swamp, drowning six of them; in 2016, another drill instructor (also drunk) drove a Muslim recruit to suicide by placing him repeatedly inside a clothes dryer. It was that kind of place. He was talking about the humidity and the sand fleas and jeez, whatever happened to so-and-so. And then, out of the blue, he asked, did you ever think of staying in? I immediately laughed, thinking, what, are you insane? I told him, no, of course not. Had you? But when I looked over at him, I realized: of course he had. A lot of folks like him had, the ones who had gone into the marines as teenagers and married young and found themselves, at 21, with a family to clothe and feed. For him, committing to a career for life wasn’t about finding something you love or living your passion – it was simple economics. Could I still survive if I don’t commit? In the end, he hadn’t stayed in, and boy, looking back, was he glad for that. But it wasn’t because the thought had never crossed his mind.

As for me, once I got out, I went back to school, majored in English, took a lot of Asian American and African American lit courses, and slowly fell into writing, beginning with zines (my first “paycheck” was a Fossil watch). Years later, I’m still writing. And even if I never become a lifer myself, I’ve gotten to meet a lot of really inspiring ones: actors and artists, doctors and academics. I’ve gotten to hear their stories and write about their lives. Sometimes I’ll ask them, if you could do anything else in your life, for the rest of your life, what would you do? There was the standup comedian who wanted to be a drama coach; the pioneering autism researcher who thought he was going to be a classical violinist. But my favorite is when they stop and pause and really think about it, and then go, hmm, I have no idea. I think I’ve always wanted to just do this.