Sometimes you have to work out what you don’t want to do, in order to understand what you do. Lolly Adefope is a writer, comedian and TV actress: three arguably very un-boring jobs. It wasn’t always this way. Here she describes how a very, VERY dull job in her twenties pushed her to work out what she really wanted to be doing.

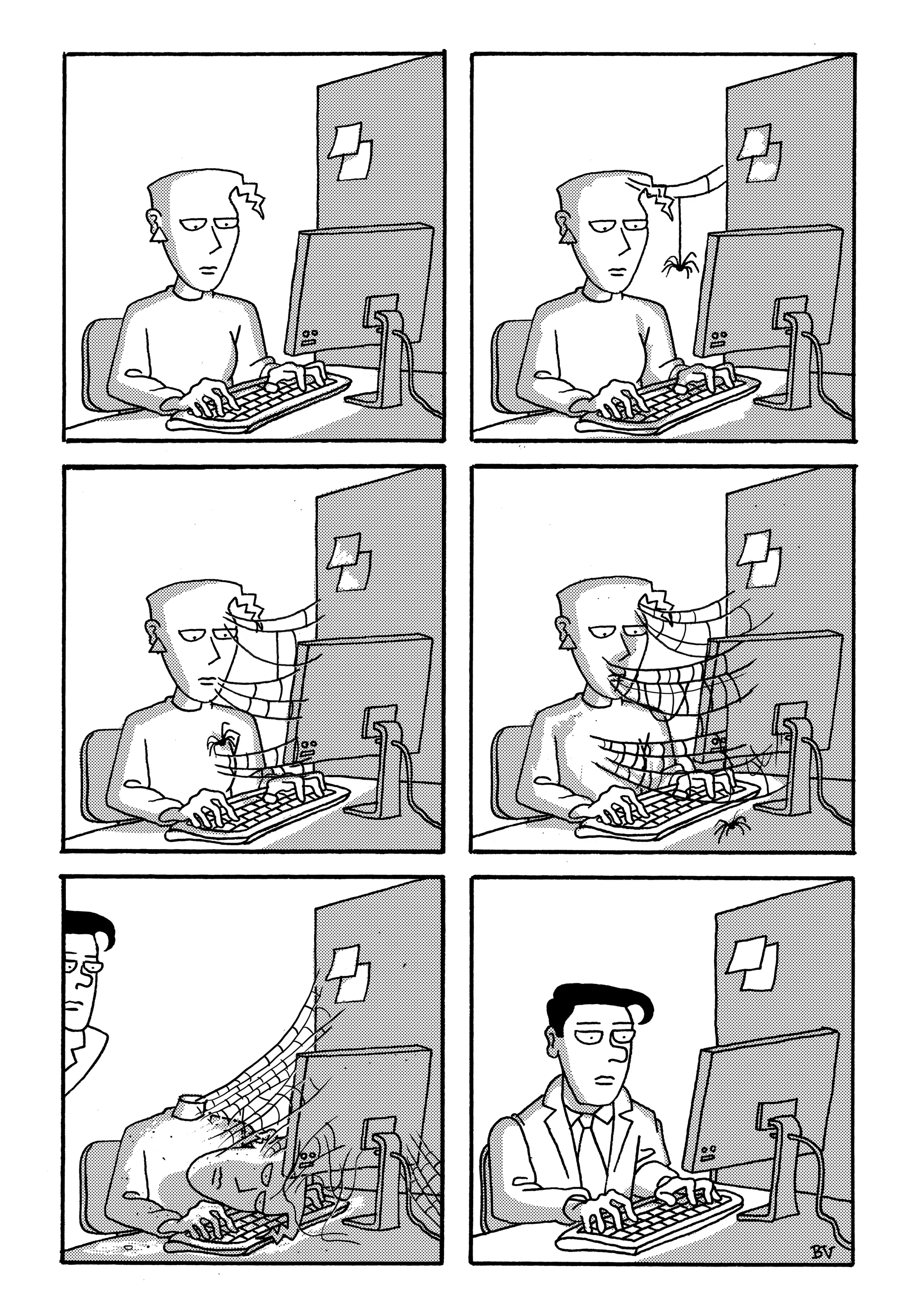

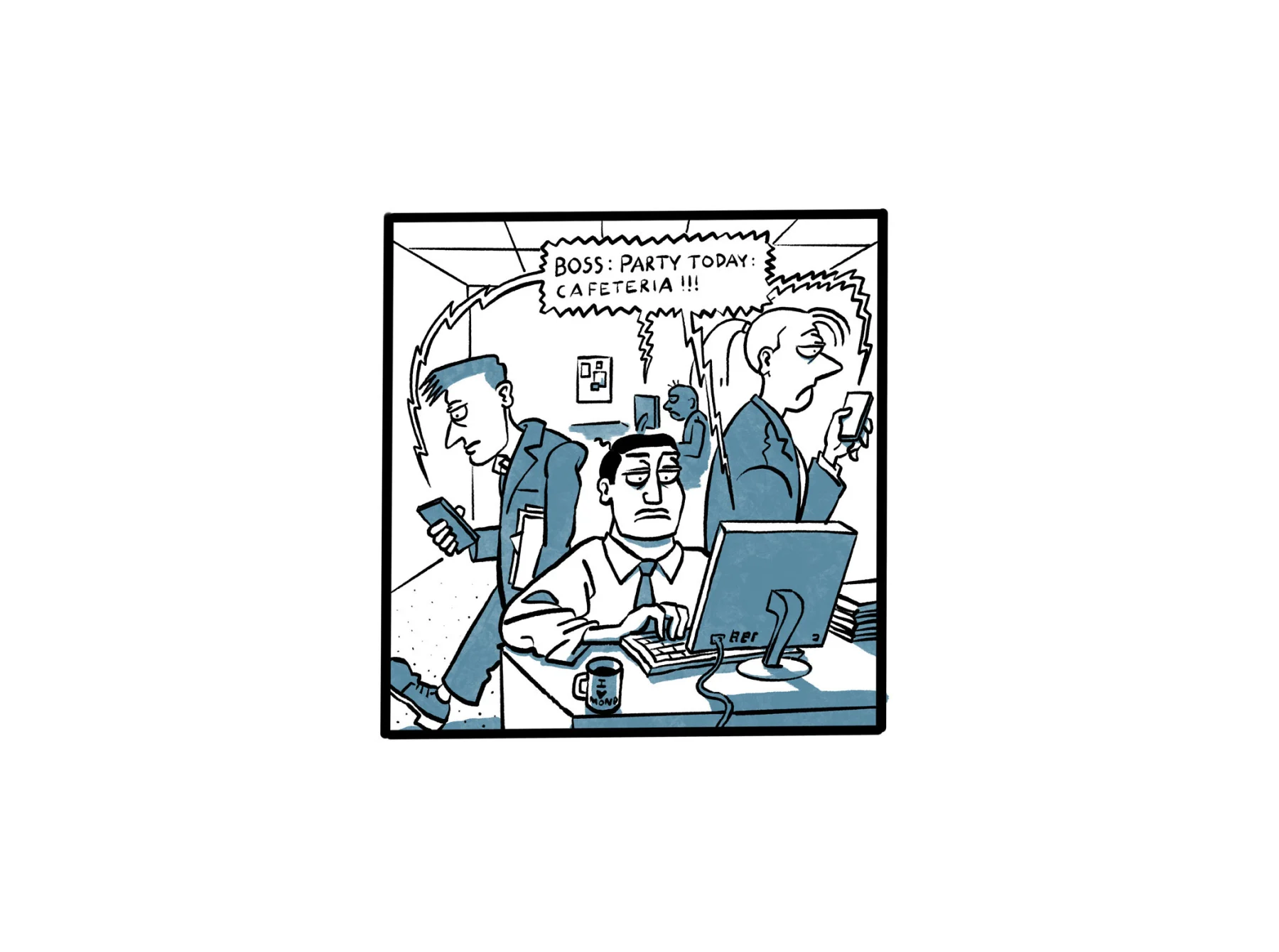

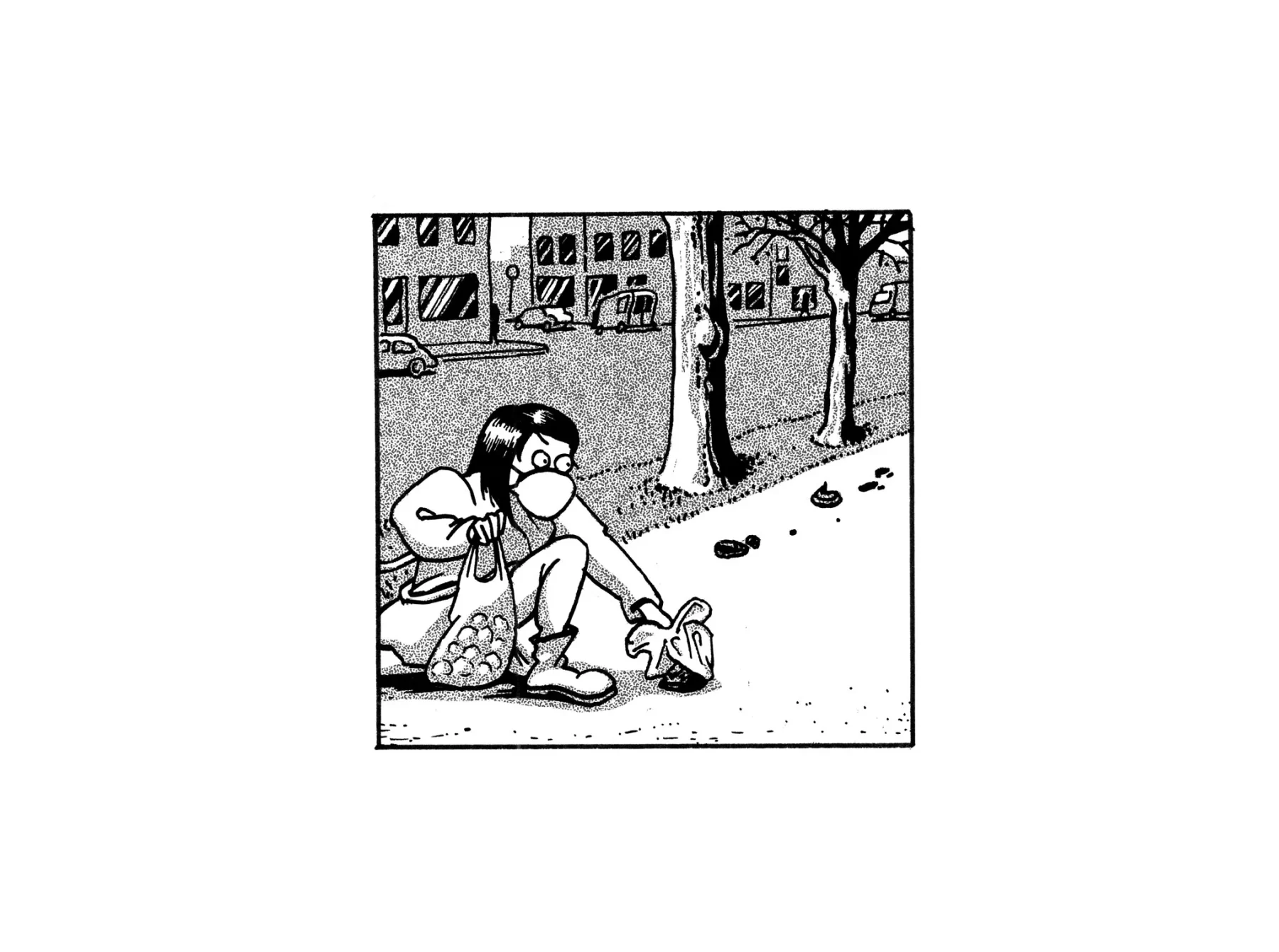

Comic by Baptiste Virot

When someone asks what you do, the worst answer you can give them is: “oh, it’s boring.” However much you insist, they don’t tend to take no for an answer, certain that they will be able to find the glamour in it – that it may be boring for you, but it surely won’t be for them.

I realised this in 2014, while working as an International Operations Coordinator for a test preparation company. The job title of course didn’t help – conjuring images of covert intelligence, far from the reality: me lying on the floor of the stockroom because I had no idea what I was doing and had somehow managed to send all of my department’s invoices in spreadsheet (read: editable) format. I would regularly find myself in a loud bar, shouting: “so it’s basically...the company that I work for runs classroom and online courses for people taking tests such as the LSAT, and SAT… do you know the LSAT? No? Well it’s a test you have to take to study Law in the US...anyway, so the courses we run also take place in lots of different countries…no I don’t run them, no, essentially my job is to oversee the organization of the classroom materials for those courses, yeah, I make sure that the teachers in the various franchise countries have all the inventory they need…yeah ice would be great actually, thank you.”

I had graduated from university knowing that I wanted to be a comedian, but with no idea how.

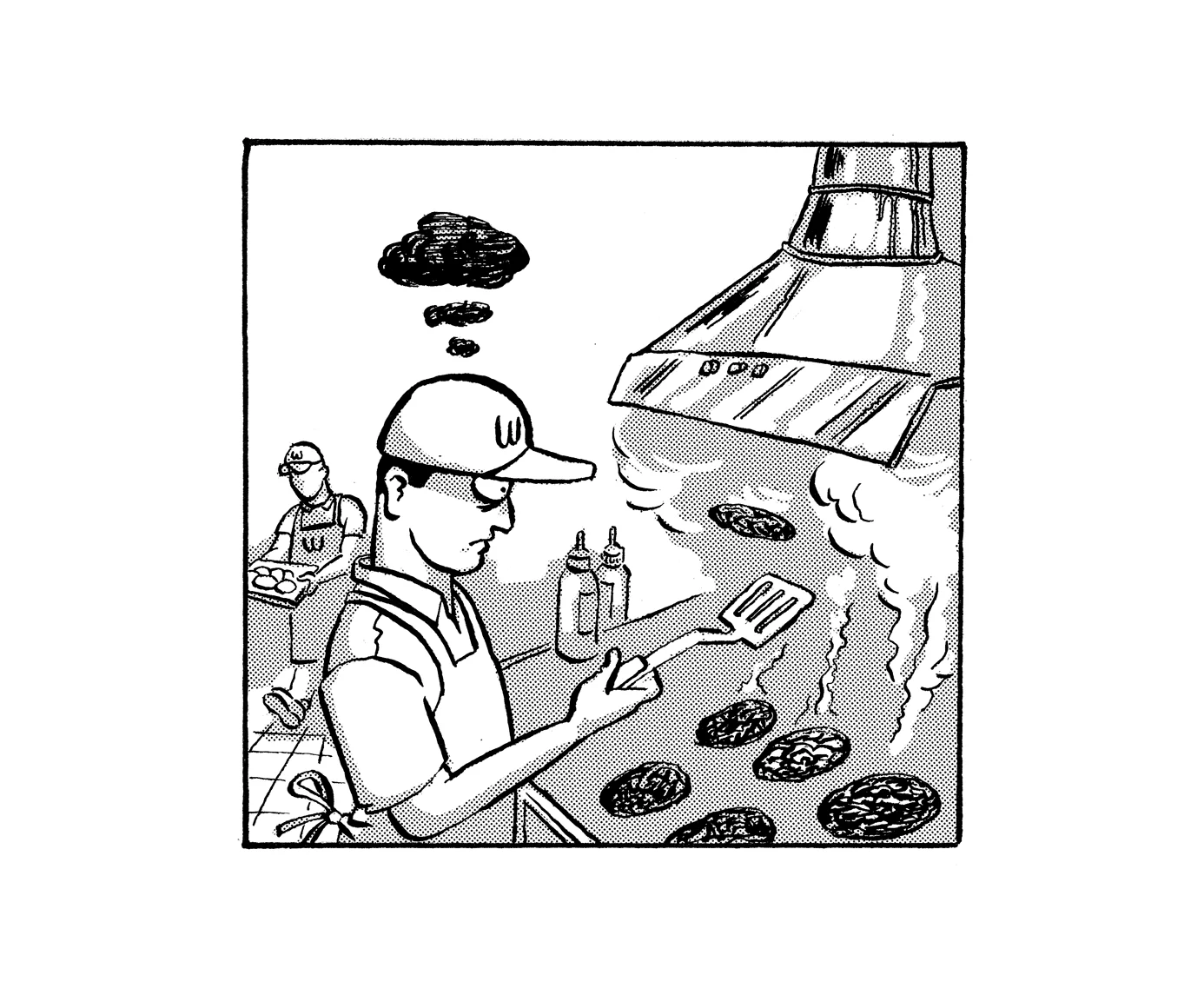

I had graduated from university knowing that I wanted to be a comedian, but with no idea how. The only suggested route seemed to be joining the Cambridge Footlights and then eventually be offered your own sitcom, and I had been rejected from Cambridge University in 2009 (post-interview, arguably more embarrassing than pre). And so I got a “normal” job, one that was an excruciating mix of tedious and difficult. But it was at least convenient: I worked in Leicester Square, which meant I could clock off at 6pm and stroll over to an open mic gig and perform for tourists who’d paid for the burger + pint + comedy package.

It was my way of turning the mundanity of my day job into fuel for the excitement of my nights.

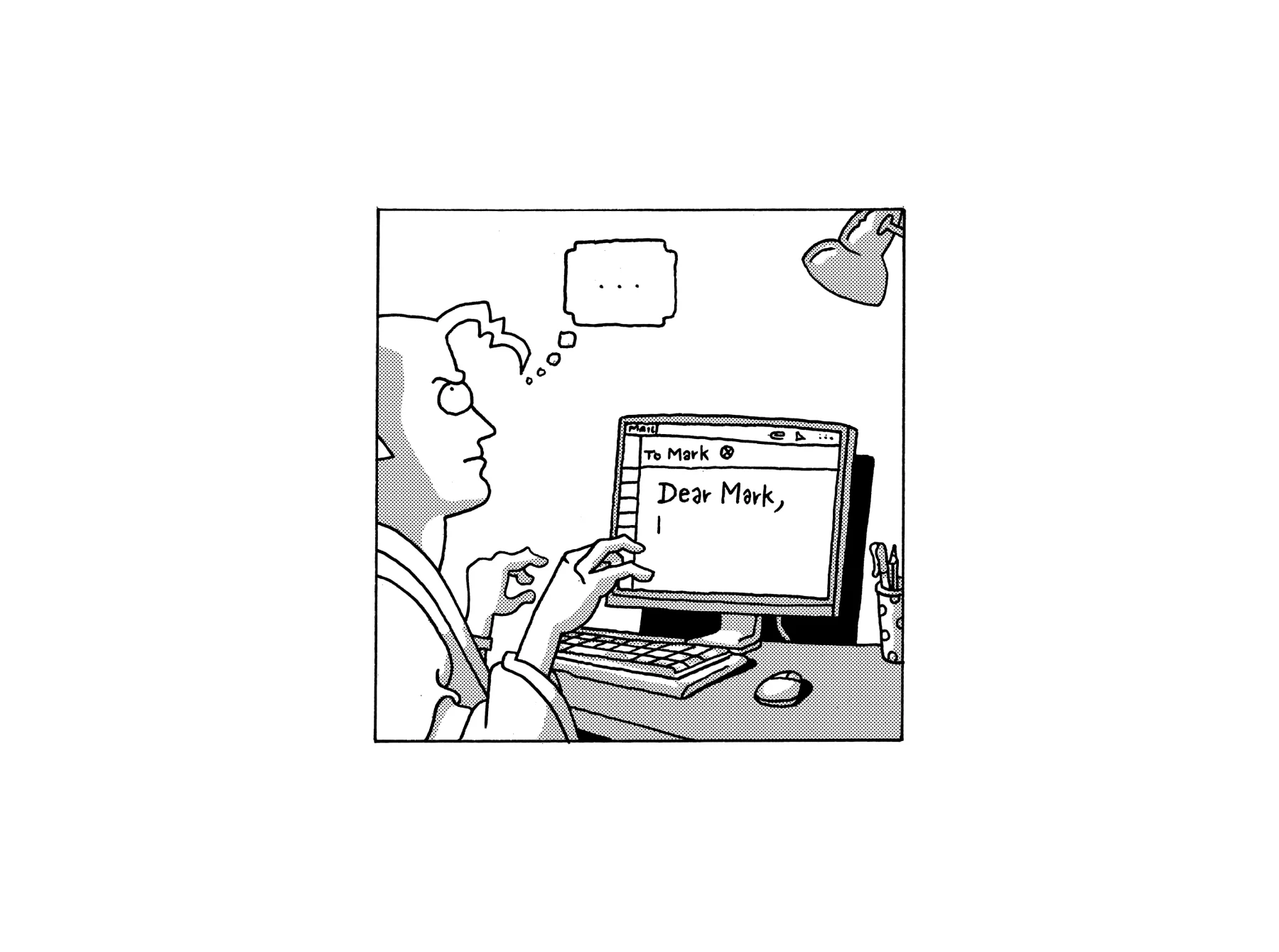

At lunchtimes I would write my material, with my first character of course inspired by my daily grind: a girl called Gemma doing her first standup gig, who invites the “girls from work” to watch as support. Lampooning someone who thinks that her extremely average life is worth talking about on stage was arguably too close to home, but it was my way of turning the mundanity of my day job into fuel for the excitement of my nights. I would spend the morning in a fog of terms that I haven’t used since, like “compliance,” “enrolment,” and “online portal,” nervous about making a phone call to a colleague in a different office who could explain to me “what exactly we do here?” And then in the evening, I’d stand on stage talking to strangers as Gemma, perfecting my best and most regionally specific Lancashire accent, before striking up casual conversation with comedians I’d long admired in the green room.

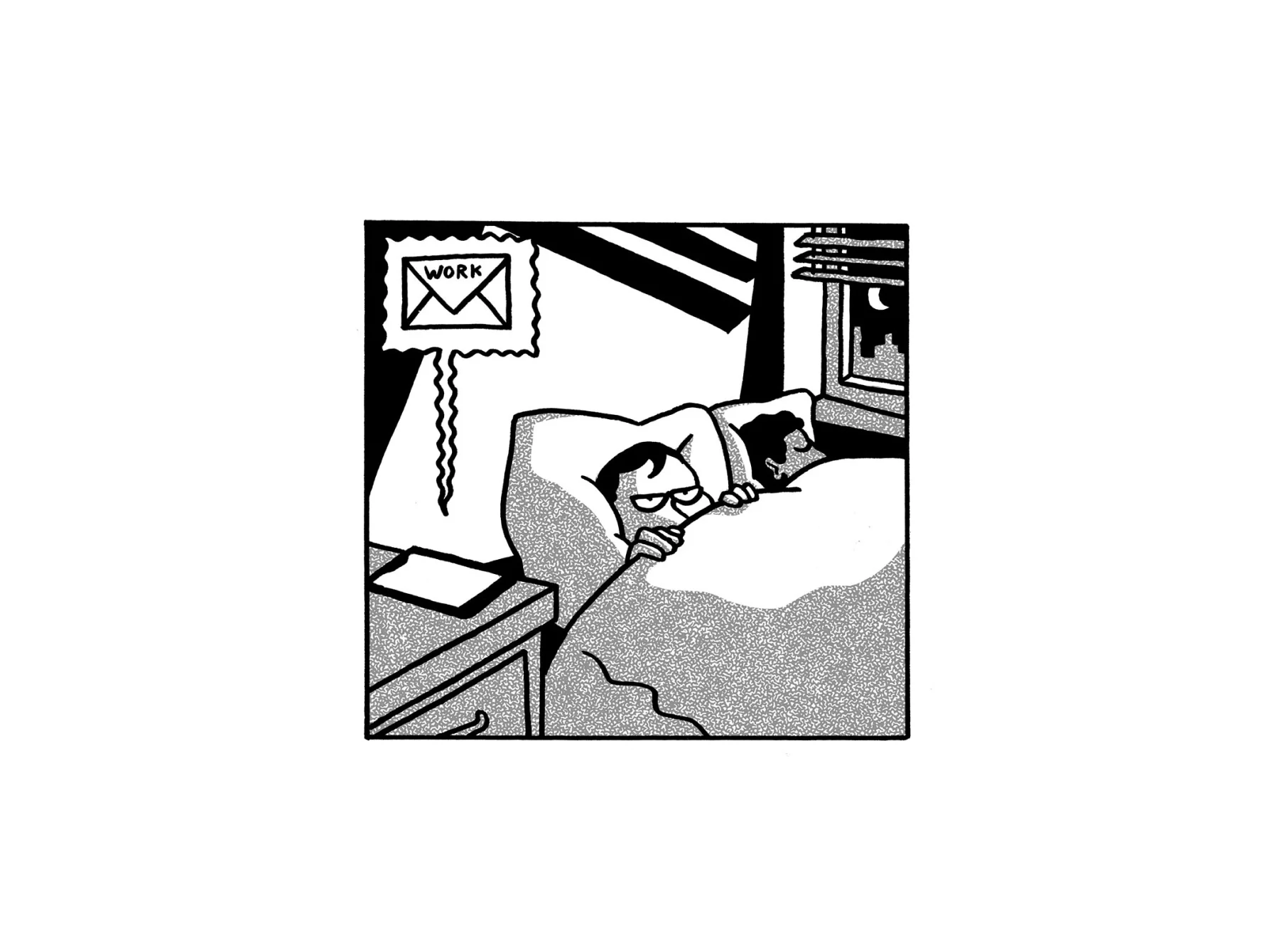

I lived two lives: one in which I was following my dreams, and one in which I would repeatedly use the term “flu-like symptoms” to explain why I couldn’t come into work (it was of course to stay at home writing jokes for a gig that evening). I was regularly 10 minutes late, “because of the trains.” (This wasn’t technically a lie, the train schedule meant that I would either be 10 minutes late or 20 minutes early, and the former just made more sense to me). I can’t say that I wasn’t grateful for the job. It meant I could move out of my parents house, and offered a fresh form of independence that was largely made up of spending half of my salary on American Apparel. Even now I miss the routine of it, as well as the opportunity to fully switch off from work in the evenings and on weekends. Being able to access my emails only when in the office was a luxury that I definitely didn’t make the most of.

I had been rejected from Cambridge University in 2009 (post-interview, arguably more embarrassing than pre)

After being in the role for six months, my manager took me for lunch for my appraisal. After politely asking me how the comedy was going (and me babbling excitedly about how I’d signed with an agent and that things seemed really promising) she let me know that from where she sat, she could actually see my screen, and so could see the large chunks of time I spent looking at photos of myself when I was meant to be working. If it were biologically possible for me to “turn red,” I would have done so. My embarrassment prevented me from pleading my case. How could I explain that I needed to choose a headshot stat, because you need one for the casting directory Spotlight, and that and you need Spotlight for auditions and I needed to nail an audition so that I could escape from this tedious prison of which she was the guard?

I handed in my notice the next day. It was clear that my two lives were no longer working in harmony, but my open mic gigs had turned to paid gigs and a small TV part as “Annoying Girl,” and that was enough for me. No more coordinating international operations! I walked out of the doors on my last day with the kind of “7 glasses of red wine” hangover that still lingers with you at 6pm, yet feeling freer than I ever had.

I walked out of the doors on my last day with the kind of “7 glasses of red wine” hangover that still lingers with you at 6pm, yet feeling freer than I ever had.

Six years later, it’s funny that an experience which at the time, felt so relentlessly uninspiring, challenged me to find the humor in the humdrum. At the time, I felt pulled in two directions, and that it was supremely unfair that I had to spend eight hours of the day sweating over impenetrable data and only 10 minutes on stage. I can see now that without the former, I wouldn’t have been as motivated to go after the latter. I was able to coordinate my operations into a career that I’ve wanted since I was a teenager, where (I hope) I offer people a chance to escape the mundanity of their own lives too.

Now, when I’m now asked what I do, I can honestly – and proudly – say that it is far, far from boring.