Many of us probably spent the majority of our early twenties not really knowing what we were doing in our jobs (or our lives, to be fair). Joel Golby is no exception. Kicking off our Work Sucks, I Know series in which writers explore how jobs aren’t all they’re cracked up to be, he explains how managing to get organized in his twenties may have saved his career.

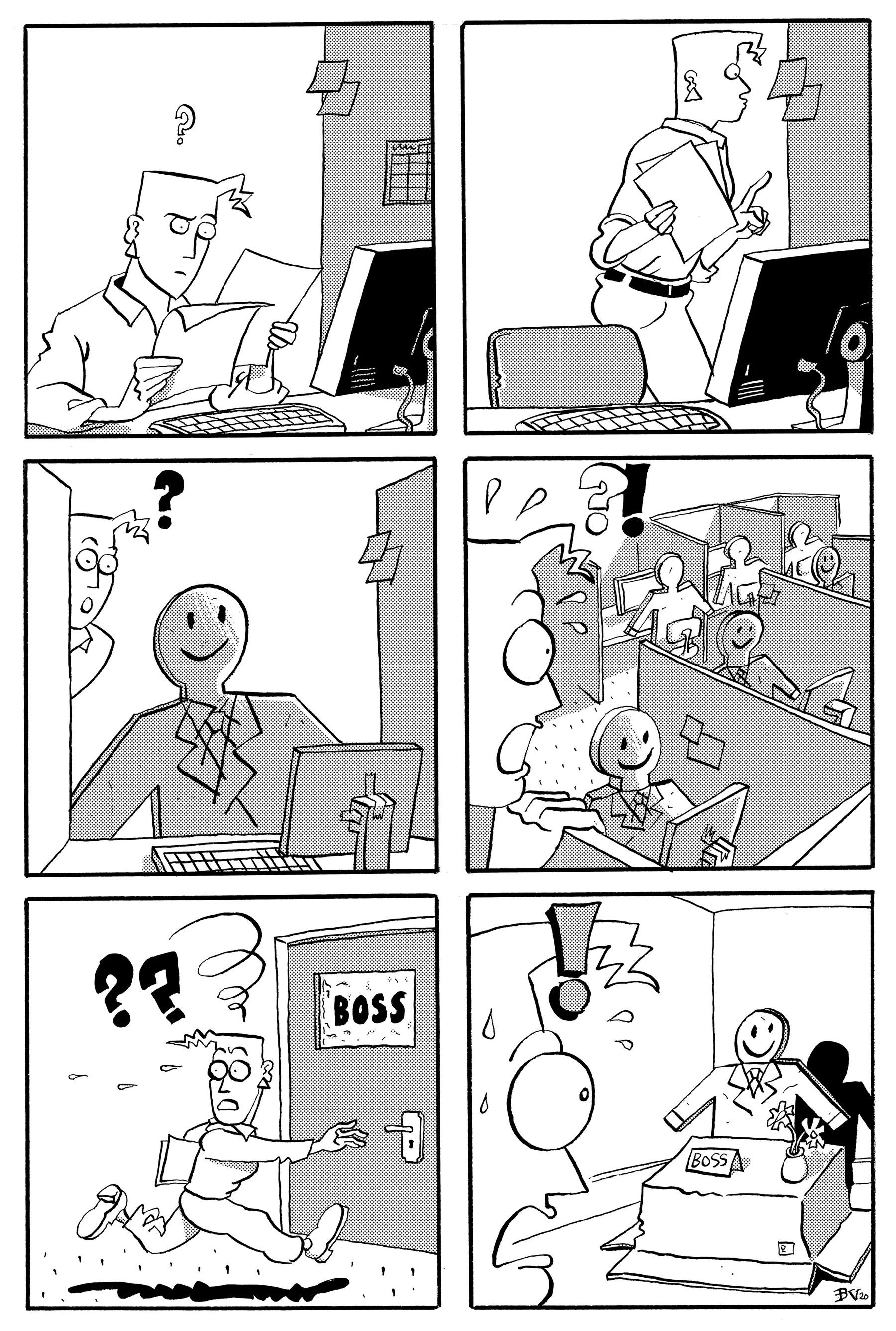

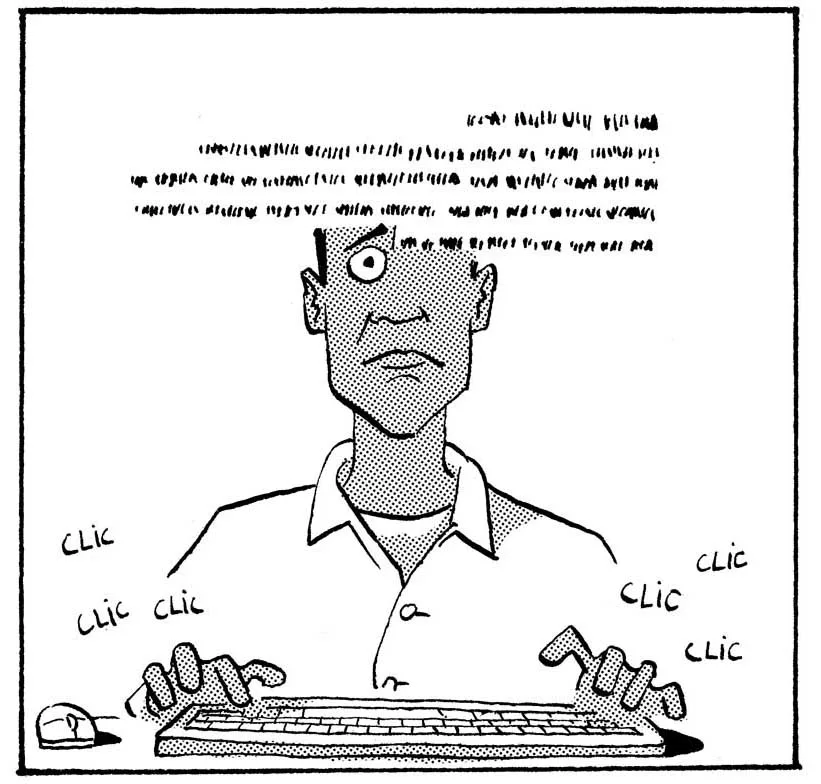

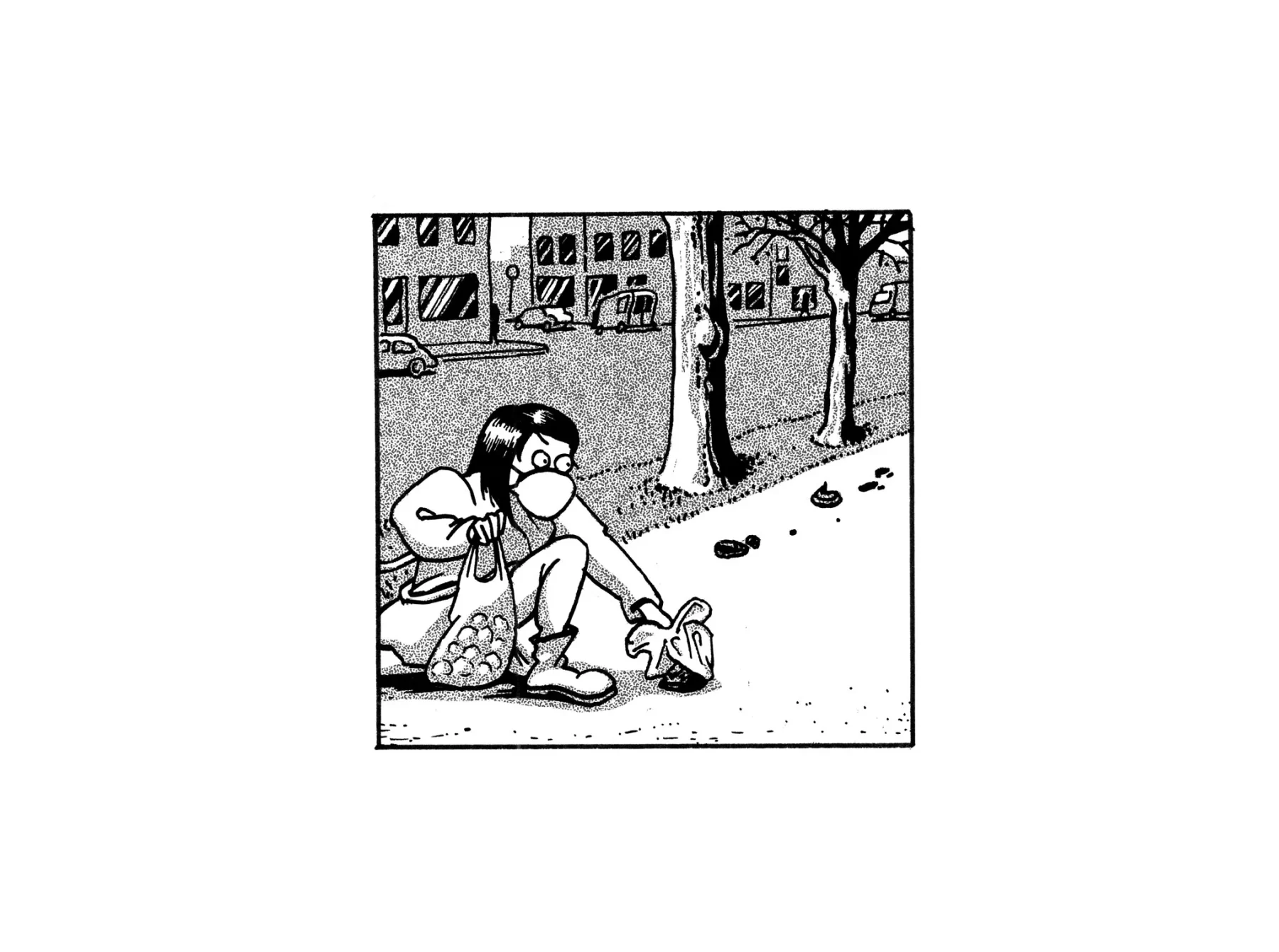

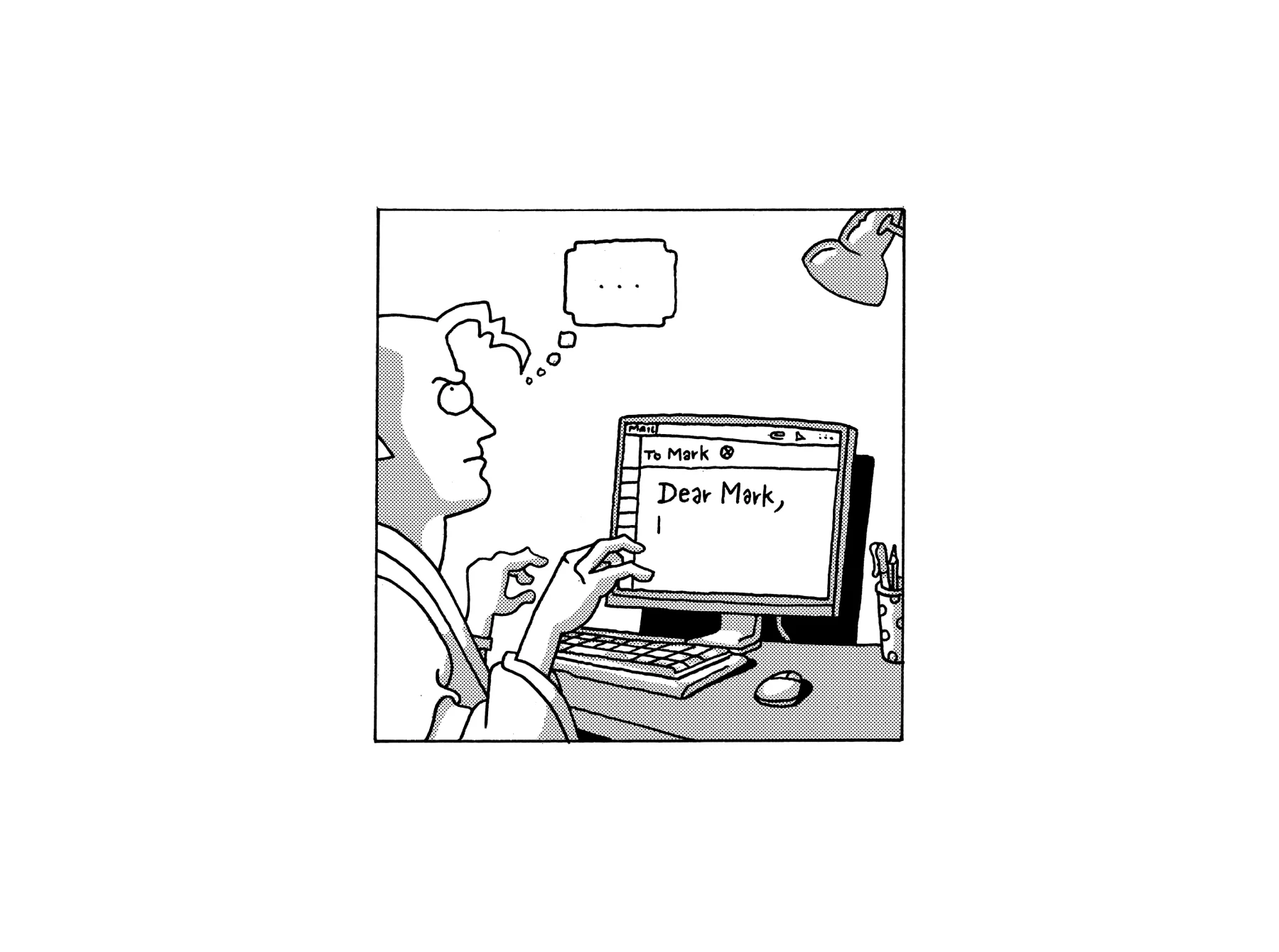

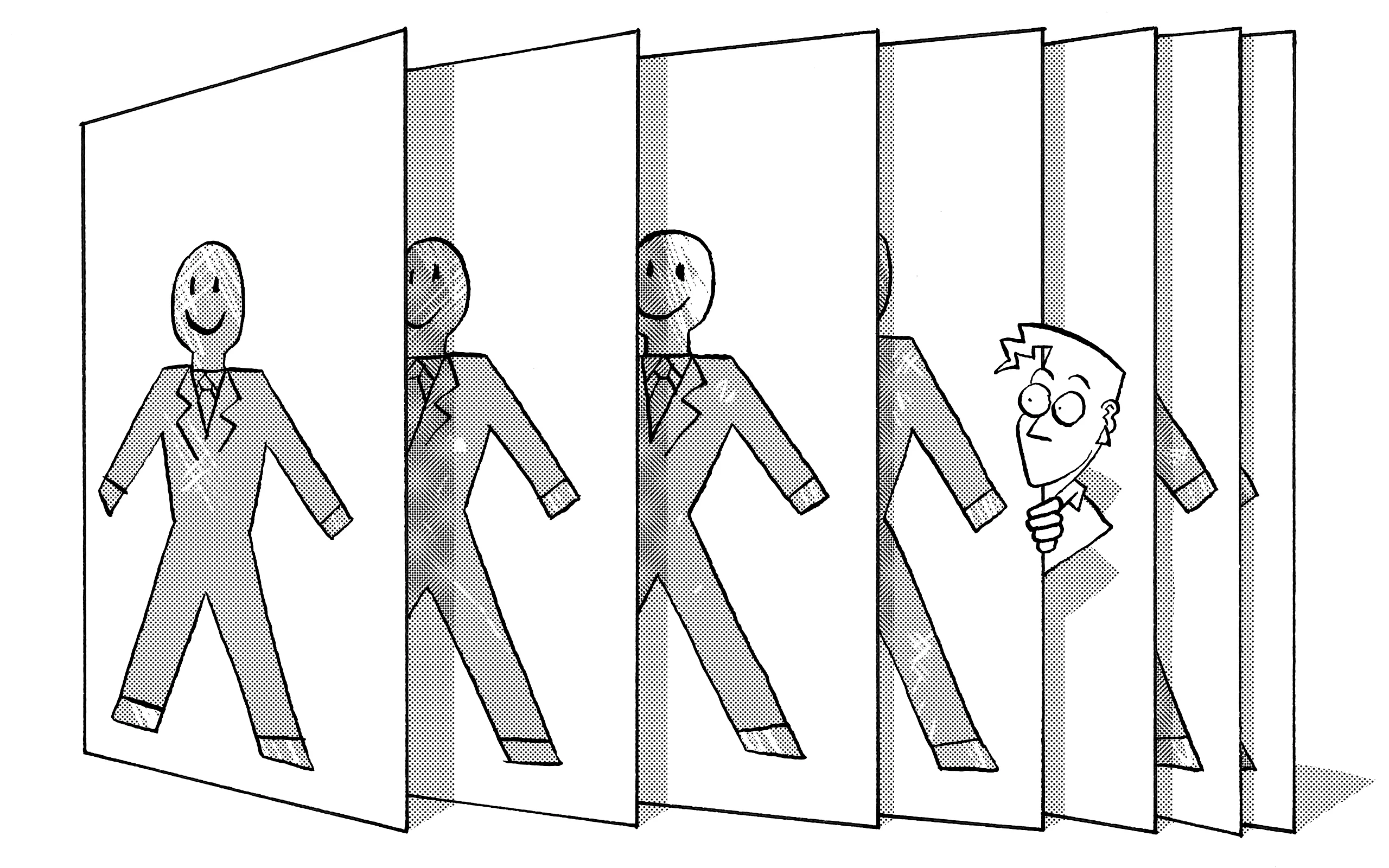

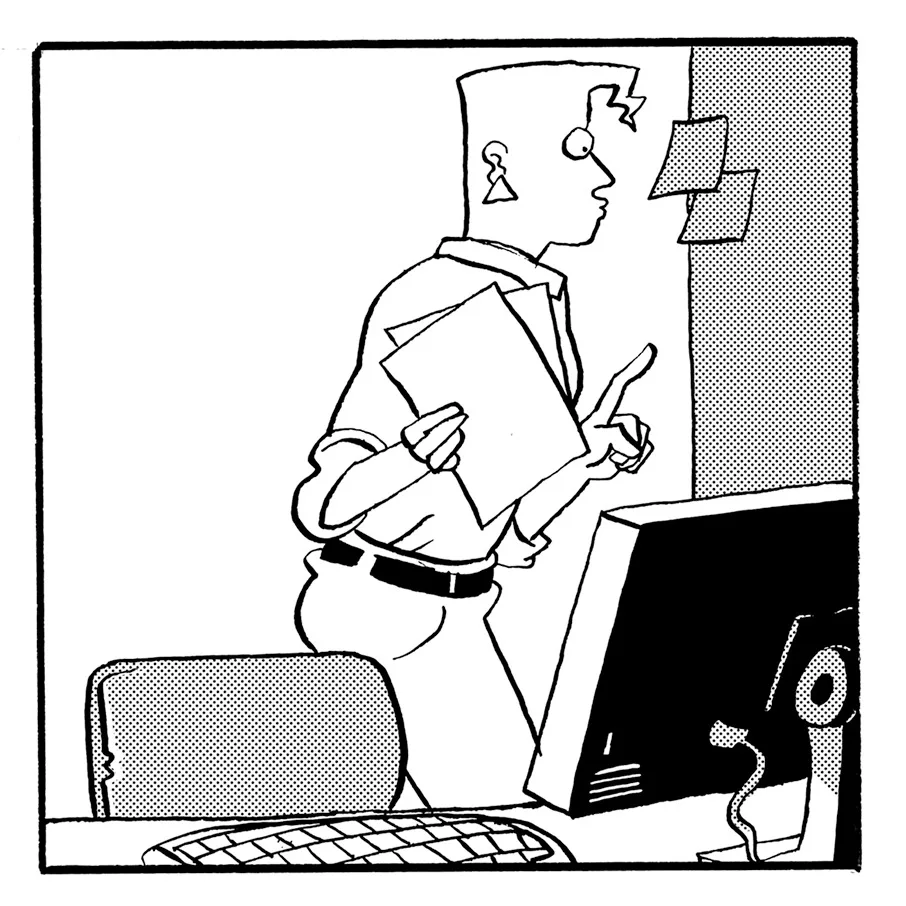

Comic by Baptiste Virot

My first job put me on a corner desk where I could see the entirety of the office but nobody could see my screen. This was the first mistake they made. There were more, obviously: they put me on a fairly passable hourly wage that meant my agitation to ever move on from the job was approximately zero; they enforced a managerial un-structure where nobody in a position of power actually knew which one of them was in charge of me, so in effect no one was; they assigned me about two hours of work, hard-w big noun, across every 40-hour working week. Mistake, mistake, mistake, mistake. I did absolutely nothing for the entirety of the first year there. And, come to think of it, for a fair amount of the second.

Doing nothing for 24 consecutive months is amazing, and I highly recommend those who are in a position to do it, but also nothing could’ve been worse for setting me up for a career where I, well, have to do things. Writing isn’t a real job, obviously, but it is hard to avoid the glare of a deadline within it: people know if you haven’t written a feature yet because, very simply, you need to email the work to them once you have created it, and if you don’t do that then it becomes very evident when you haven’t. I wrote a book a couple of years ago and had to roll up to the first soft deadline, head in my hands, and admit I hadn’t actually written it yet, I’d only done about 75%, and a lot of that 75% was unusable garbage. “It’s really hard to write an entire book,” I pleaded. “It’s really hard to concentrate that much. I keep getting distracted by making sandwiches, watching TV, or just leaving the house and walking around aimlessly.” Every day of my working life is just a war I have to wage upon myself to get me to do anything at all. The most exhausting part of my job is convincing myself to do it.

Are we supposed to work? That’s a question of the human condition, a question that pierces to the heart of society. If we stare too directly at the white heat of that question then civilization starts to crumble around us. So I can only answer for myself, really, and: no. Absolutely not. Why would I want to do things? Money, obviously. To buy necessities and trinkets. But I would rather just have those things without having to toil towards them. I’d always just rather they were there.

First jobs, then, are a fairly decent tone-setter for the rest of your career, as well as an abrupt and steep learning curve in the reality of existence. The usual path up to that first job is fairly coddled: primary school, where you are effusively praised for reading a book; secondary, where you are coached in exam-passing and little else; sixth form, a sort of first-beer-and-trying-to-take-up-one-hobby-that-impresses-admissions-officers period of growth; then university, which is just staying up late in historic libraries writing urgent essays based on books you haven’t fully read. And then you are plumped in front of a computer, given an email address, issued a laminated office pass and told to get on with it. What, nobody is going to check up on me constantly, making sure I’m doing what I’ve said I’m going to do? You’re just going to give me a computer with unlimited access to the internet and trust me to use it wisely? And you’re going to pay me for this? It’s a wonder anything gets done. The workforce is constantly being fed fresh, new, clueless under-25s in the same mould I was in – hesitant to work, not knowing how to work, and unmotivated to do anything – and we wonder why we keep having recessions. We keep having recessions because of people like me.

That first job – an admin assistant in a university drama department – wasn’t a job, per se, more a complicated exercise in seat-filling. I am convinced that this is indicative of a hidden middle class of office jobs: offices, run by office managers who have spent years working in the office in various pre-managerial roles, observing exactly how the office works and why, ascend to a position of power and decide to duplicates exactly processes and people that came before it. But what they neglect to understand is offices aren’t complicated engines that require precisely-geared component parts, because most of the jobs in them are just “sending emails.” Most offices would run just fine without about 30% of the people and some cleverly phrased auto-reply functions. But they don’t, and so: I was brought in as cover for someone who had left after covering for someone else, who was covering someone who left during a department reshuffle four winters ago. The last time anyone actually had the job I did was two, maybe three years before. At no point in that time did anyone check whether the job still needed doing. They just assigned the budget, turned on the computer, and filled the chair with a human. My employment was a resolved remainder on an outdated spreadsheet. I was the solution to a problem that didn’t exist.

This was fine because it meant I didn’t have much to do and nobody questioned why it always looked like I wasn’t doing something. My week had certain beats and rhythms – there was a Friday afternoon job that involved carefully push-pinning paper sheets to cork boards mounted on doors which I looked forward to a lot, because after I was done it meant that my working week was, truly, over, and there was a really nice pub a 40-second walk from the office – but more or less I had the rest of the time to myself. I scrolled Twitter. I tapped out blogs and writing samples in the hope that I would get inexplicably noticed for them. I read a lot of those very particular forums where men discuss football in too much detail for it to be healthy. I found a seemingly abandoned fourth-floor bathroom nobody seemed to know about that I could, should I have chosen to, very quietly died inside without anybody noticing for a number of months. Occasionally I had to print something out on headed paper, or order another box of headed paper for the print-outs, or sit at a customer service desk pulling a screwface. But broadly I just sat there like a loaded gun: ready, obviously, to do some photocopying if someone really needed it, but fundamentally unused.

For a 22-year-old with my particular lean towards laziness this was, I have to admit, paradise. But then there’s some old story about paradise, isn’t there, and it being bad? I feel like I’m paraphrasing it. I feel like I’m misremembering the details. Something about snakes, and apples, and original sin? Something about the vengeful rage of God? I don’t know. It feels ominous, the story, whatever it is.

My brain wants to run wild through a field and somehow make a paycheck for it afterwards, but that is not the reality we live in.

A little while into my second year there my manager tweaked his back in such a spectacularly significant way that he was essentially bedbound for a summer. This, I took, as even more of an opportunity to goof off. I’d turned up in London with big dreams of making it as a writer but instead I figured out a very precise angle my computer screen could lean so people couldn’t see when I was playing Minesweeper, so did that instead, and I was looking forward to spending the June to September working on my hi-score. Quietly, in the background, there was a mild brooding sense of panic: was this it? Was this the rest of my life? Is this what I’d given up friendships and the sanctuary of home to do? Was I put on this planet to lazily administrate a university drama department? But broadly I quietened those fears. I could do this for five or six more years then figure my life out. And then I answered his phone the first day he was off sick to tell whoever was calling that he wouldn’t be in for four months, and to call back then. “Ah, Joel,” my manager said down the line to me. “Just the fella.” Mistake, mistake, mistake, mistake.

The arrangement here was this: he would do his job, from home, but I would be the hands that did it. I would sit in his chair (way better back support, to be fair), and he would sit in his bed, and I would use his mouse and his keyboard, and log on to his computer with his password, and answer emails in his voice, and he would tell me how. Every morning he would call me, and me alone, and I would press the phone up to my ear until they both ran hot, and for four or five straight hours I would do his job. After I put the phone down I still had some more of his job to do, and my own job as well. This was great for me, but also terrible for me. I finally had to do a job in a way where people would know if I didn’t. Which meant, abruptly, I had to teach myself how to work.

Every day of my working life is just a war I have to wage upon myself to get me to do anything at all.

Some people have a work ethic, and I’m proud of them all. But I don’t. The challenge of any single day is for one half of my mind to trick the other half into doing something, but neither half can really do a neat job of doing that, because both of them default to being lazy. Brain #1 wants to play PlayStation and Brain #2 wants to let it. There are no adults in the room. Both brains want to do something sordid like crack a can of Stella and watch an entire hour of pornography. This does not pay rent. This does not keep daddy in trinket money. We must guide the tiger into the cage and wrestle it into domesticity.

And so I taught myself how to do a job. Stationery rapidly became important to me. I have feelings about pens and fine paper like normal people have about The Royal Family, war, the legitimacy of taxes. The generic blue biro is the worst pen in the universe, for instance. I think that. I regularly have that thought. Sometimes I see blue biros and mentally recoil away from them. The blue biro is a path to inefficiency. It needs to be quashed. Notebooks can be finely lined (though I prefer the sophistication of a grid, or the intellectualism of dots), but I don’t want it to be ringbound: I need to crack it like a book. The weight of the paper needs to be able to take some fairly heavy black ink. It needs to not press through onto the unlying pages. I can’t have bleed and I can’t have smudges. If I write something down it needs to stay there, on the precise page I wrote it on and no others, and not leave a sentence pressed into the side of my hand. (I walk around with these opinions pressing against me, every single day). Electronic lists exist and I’m happy for whoever has found peace with them. But the only way I use technology is to send my computer an email from my phone so, when I get to the computer, (with my notebook next to it), I can write the email into my notebook and delete it from my records.

This borders along the fine edge of psychopath, I know that, but stringent list-making is the only tool that works. I am convinced humanity is split into exactly two halves, and that race and gender and age and religion can all be abolished and replaced as an identifier with this: are you organized, naturally, or are you not? On the side of chaos there is me. On the side of order there are like a thousand books about getting your life together that I’m never going to read, precisely because of the chaos that lives within me. And in between, cobbled together with gaffer tape and discarded wood parts and hot glue, there is a barely functioning system of my own design: Writing Things Down And Then Doing Them. It is the only thing that works. I learned it while pretending to be my manager ten years ago, and I haven’t been able to abandon it since.

Slowly this infects your lifestyle. If my manager hadn’t got out of bed awkwardly in 2010 then I doubt I would have learned to do his job, and then my job, and then jobs in general, and then I (long story) got fired (it’s a long story) from that job I’d finally learned how to do and took my new job-knowing skills out into the world and I was finally able to make the leap from “professional Minesweeper player” to “writer.” The process of being in your twenties is a reflection of this, I think, learning small lessons of adulthood that accumulate to a more organized and assembled whole: leaving the pub after three pints on a Tuesday instead of pushing through to five or six; learning not to leave laundry in the washing machine for more than 24, maybe 26 hours at a push; A Sensible Weekly Grocery Shop Lasts Longer And Costs Less Than Buying Ingredients Every Day From The Store. Slowly you draw an outline of an adult, then sketch in the shadows, and finally fill out the form.

My list right now says “write a moral to this story,” and I can’t, because there isn’t one. I am convinced that organization cannot be taught to the chaotic by the already organized, only by the naturally chaotic: yes. The neat systems of organization preached to us by people who actually did their homework in school are useless for the likes of you, (I assume you’re disorganized: what you are still doing here if you are not is beyond me), and me. Embrace the chaos of a system unmade – teach yourself how to make it work. I am thankful to that first job, for first letting my mind rot like old fruit, for descending into a pit of inactivity and a loss of hope, for allowing my to stare into an abyss where I could feasibly do these same repetitive administrative tasks forever, and then allowing me to sharpen up again, into – well, not into a blade exactly but into something capable of putting a dint in some bread. Because the truth of the matter is, still, all these years later, I don’t want to be doing anything. I don’t want to be doing this, right now. My brain wants to run wild through a field and somehow make a paycheck for it afterwards, but that is not the reality we live in. What reality I have is this: a pen, some scandalously thick notebook paper, a firm square box with a job or chore written next to it. The only way to make myself do anything at all is dangling the soft delicious crumb of job satisfaction in front of myself – the yummy, yummy lizard brain hit that comes from ticking “done” on an item I’ve been putting off for days, for weeks. It’s coming, now. I can see the list next to me, I can see the box, I can see “FINISH WETRANSFER ESSAY, IDEALLY WITH A SOLID CONCLUSION,” all of it twinkling, looming. I know I get to tick it, in a second. I know I get to tick this job off, and bask in the glory of having done it. And it gets to happen

— now.