Alex Moshakis is an editor. His working day revolves around rearranging the order in which writers place and use words. Beautiful in how subjective, ambiguous and infinite they can be, words are endlessly fascinating in their variety and ability. But despite that, Alex pines for the security, the finality and clarity of working with numbers. Here he explores why.

Comic by Baptiste Virot

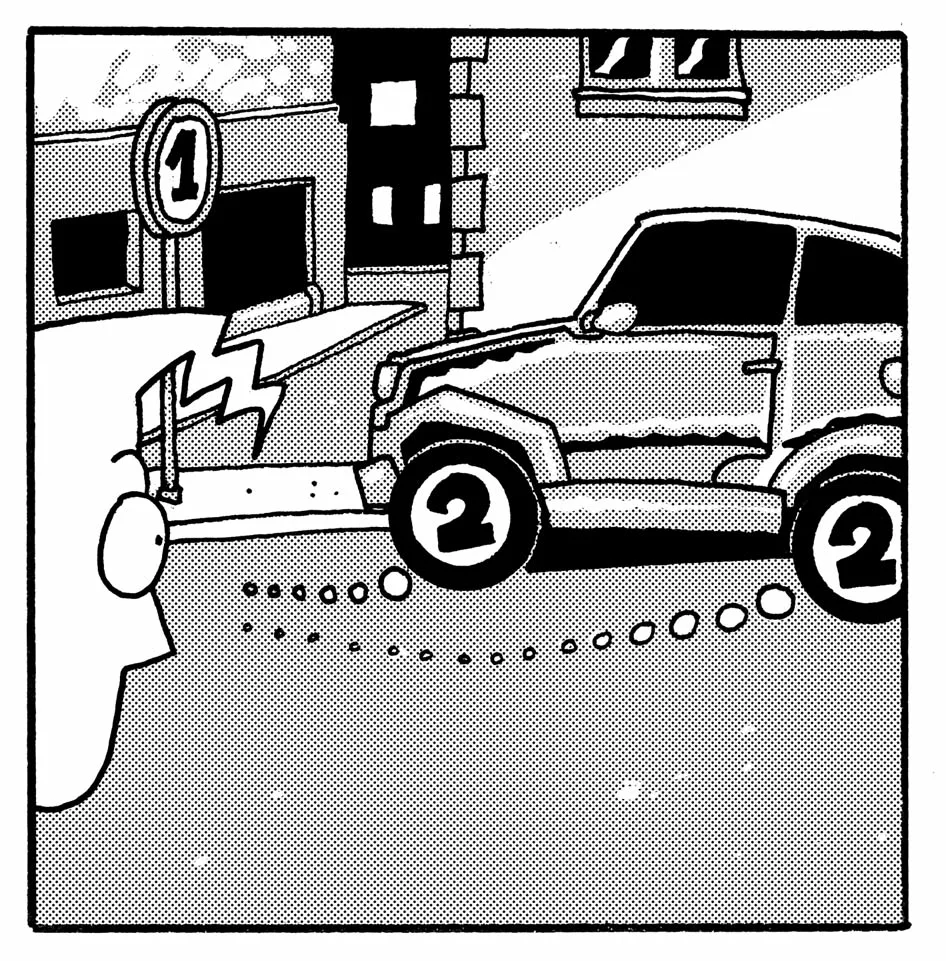

One of the first pubs I worked in did not have electronic tills. This was in 2001. I grew up in a small town near Birmingham, in the West Midlands. We had cars. We had mobile phones. It wasn’t 1840. Every other pub in the area had electronic tills. Just not the one I’d picked.

A few friends and I had asked for jobs at the same time and most of us had got them. We were 17 and 18 years old, which meant that only some of us were working legally. It didn’t seem to matter. The landlord interviewed us and then rarely spoke to us. He was quiet and withdrawn, unloaded with personality, at least around young people. He appeared near to the end of every night to count the day’s takings, and sometimes he checked in to serve the regulars. But otherwise we’d have the run of the place.

There was a rumour going around – at some point, I can’t remember when – that the landlord had been somehow so emotionally crippled by the threat of the Millennium Bug that he now completely avoided computers.

But it was only a rumour.

“You will have to add the prices up yourself,” he told us during a training session.

For a moment, we didn’t understand.

“You will have to add up the prices.”

For most of my working life, as an editor working at magazines, numbers have only played cameos in my day.

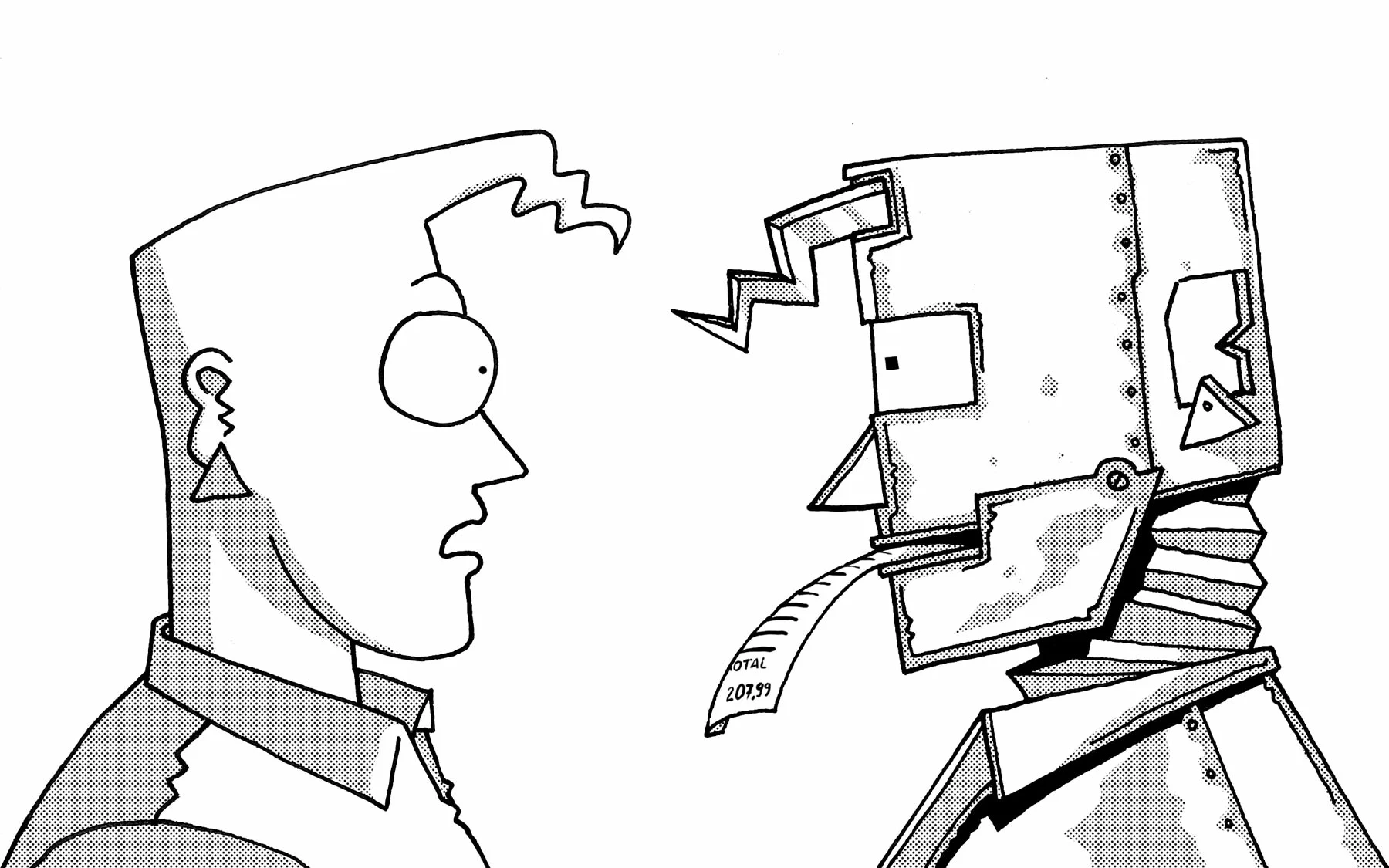

He meant that, as we served customers, it was our responsibility to hold the prices of drinks in our heads and produce a final sum, because the tills didn’t have the capacity to do it for us. This would be easy when a customer ordered one drink, so long as we quickly learnt how much individual drinks cost. But it would become more difficult when the order was larger and the pub was busy. The pub had a huge landscaped garden that backed onto a canal. It was pretty and very popular, which meant that it was nearly always busy. I remember the landlord telling us that he would be unhappy if we got prices wrong, though he didn’t offer it as a threat. He would just be upset.

In the beginning, the adding up was difficult and time-consuming – so many drinks, so many prices. A customer might approach the bar with the same order on two separate occasions and receive wildly different totals each time, which was fine when we charged less for the second round and tended to end disastrously when we charged more. But, slowly, the process became easier. After a while, we no longer had to mouth the numbers as we added them up. We stopped lingering at the till so as to finish sums. Eventually, we tended to be right more times than wrong, and then it became rare that we made a mistake. The numbers became familiar. The process of adding up became mechanical, a whir that went on – quietly, smoothly, uninterrupted – in some background of our minds. We completed a thousand or more sums a shift, and every addition was a right answer and a tiny, unnoticed accomplishment. Soon, the numbers didn’t trouble us at all.

There are no definitive forms or narrative structures for a piece of writing, no wholly unshakeable paths.

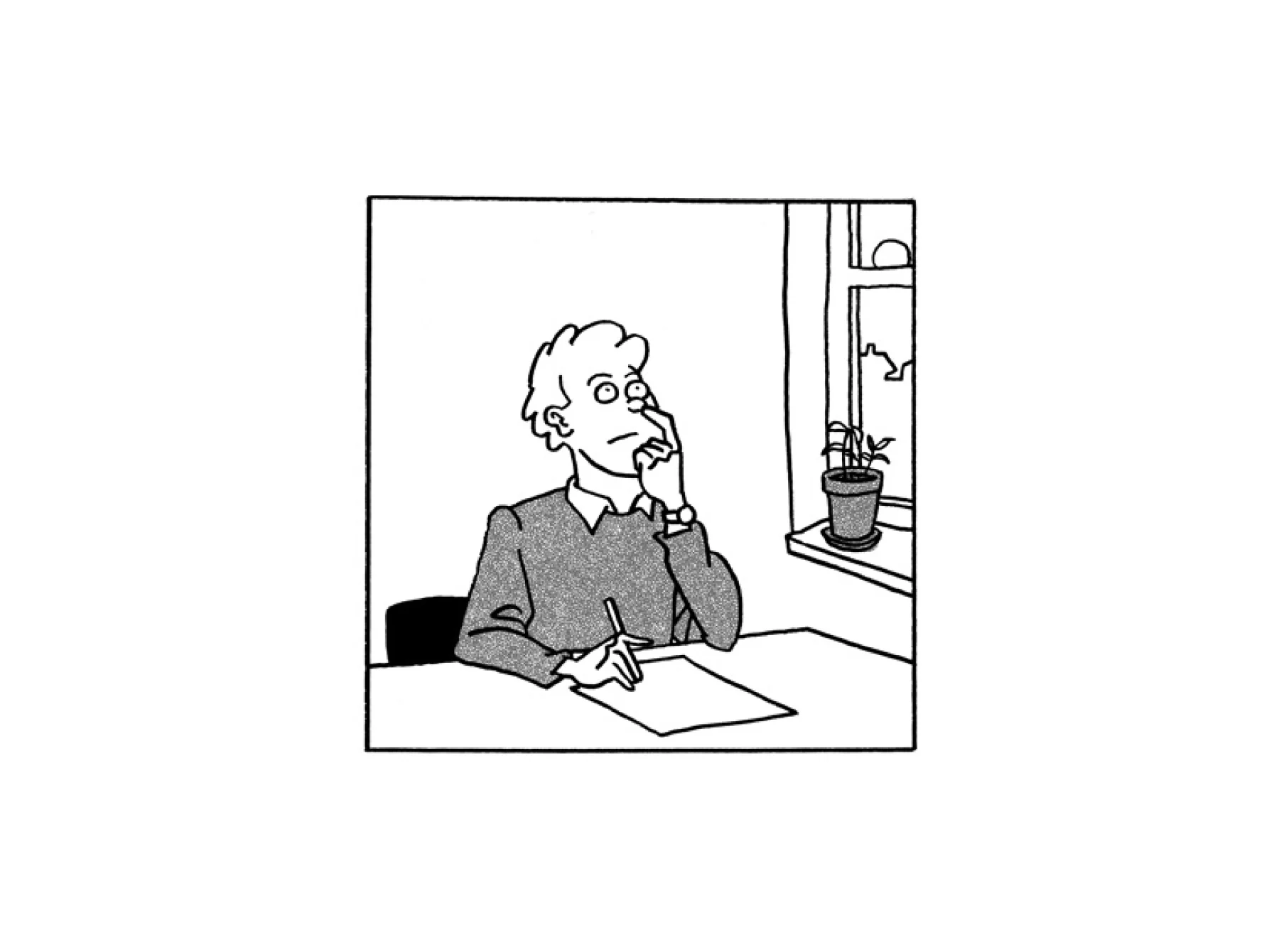

I didn’t think about this much at the time. Really, I didn’t think about it at all. But now I do. For most of my working life, as an editor working at magazines, numbers have only played cameos in my day. I do next to no addition at all. There are budgets and fees and word counts, but only sometimes. Other than that there are sentences.

Mostly my job has involved talking with writers, and reading their work, and making suggestions as to how their work might become better, more comprehensible, more meaningful somehow, or at least more direct.

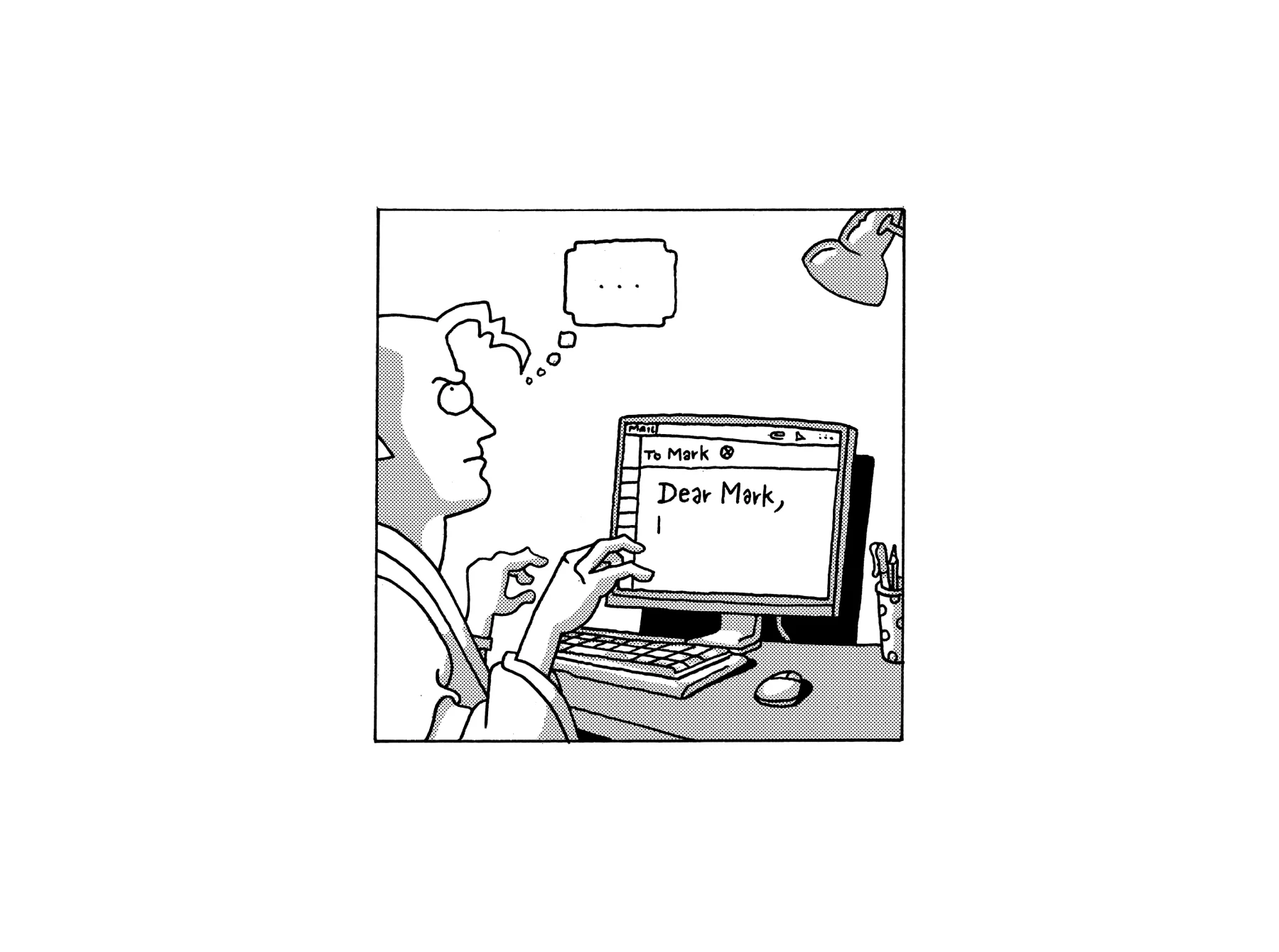

Here is a typical editing exchange:

Me: Very good. Section one seems unnecessary. Suggest leading with the second section…

Writer: OK.

Me: Second thoughts: section one helps readers understand section four, but suggest you clarify section three…

Writer: Yup.

Me: You know what? Suggest now running section two before section one, and leave section three as you originally had it, so section four leads on to…

These poor, poor writers.

But wouldn’t it be comforting, I sometimes think, to be able to arrive at only one possible answer?

Most of the suggestions I send when I am editing a piece of work begin with the words “Maybe,” “Perhaps,” “Suggest,” or “Query” followed by a colon. (As in, “Query: Have I done enough to frustrate you yet?”) Because I’m not a tyrant, rarely do I say, “I’m just going to go ahead and change this myself.” This is mostly out of respect to the writer – it is their story; I am here to guide, mostly – and because my comments are often only ever suggestions, some more urgent and necessary than others, all I hope helpful. But it is also because there are no definitive forms or narrative structures for a piece of writing, no wholly unshakeable paths. A story will unfold differently when two different writers report it. It might unfold differently if the same writer begins reporting a story on a Monday rather than a Thursday. (There is good and bad writing, but that’s a different thing). The above exchange is not an example of indecision, though I’ll admit it looks like it. It is a crude acknowledgment that, really, beyond the essential facts, a piece of writing can pretty much take any form, so long as that form is true and readable and understandable and engaging.

(There are exceptions to this process. For example, when a writer gets something factually wrong. Given that most of the writers I work with are bonafide pros, these moments are rare, but I secretly cherish them when they occur. What luck, to find a mistake that can be corrected objectively!)

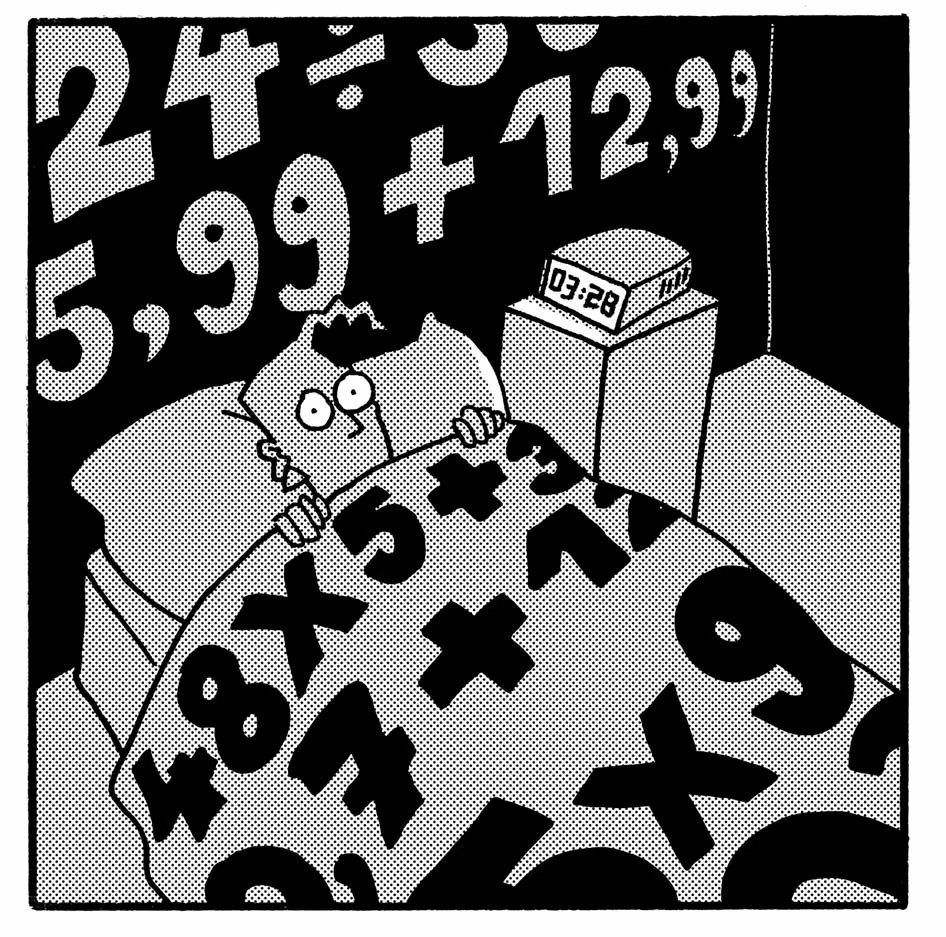

The writer Susan Orlean recently described the blank page as “a horror show.” What about the page filled with someone else’s excellent but jumbled words, presented as an almighty puzzle it is your job to solve? I’m not complaining. Really. I’m fortunate – this is the path I chose. And there is a lot of excitement in scanning a draft and holding in your head its possibilities. It’s just that there are usually so many of them, so many directions in which a story might travel. This is the thrill, the potential of a structure you can’t yet see. But wouldn’t it be comforting, I sometimes think, to be able to arrive at only one possible answer? Wouldn’t it be a relief if the process were at least sometimes one of definites? Like a pub job that involves adding up the prices of drinks? Which I suppose is a roundabout way of saying I miss those numbers sometimes, their bluntness and certainty, their reliability – the right and wrongness of it all – and also an acknowledgment that the crux of an editor’s work, forging a piece of writing’s final form, can be as troubling as it is gratifying.

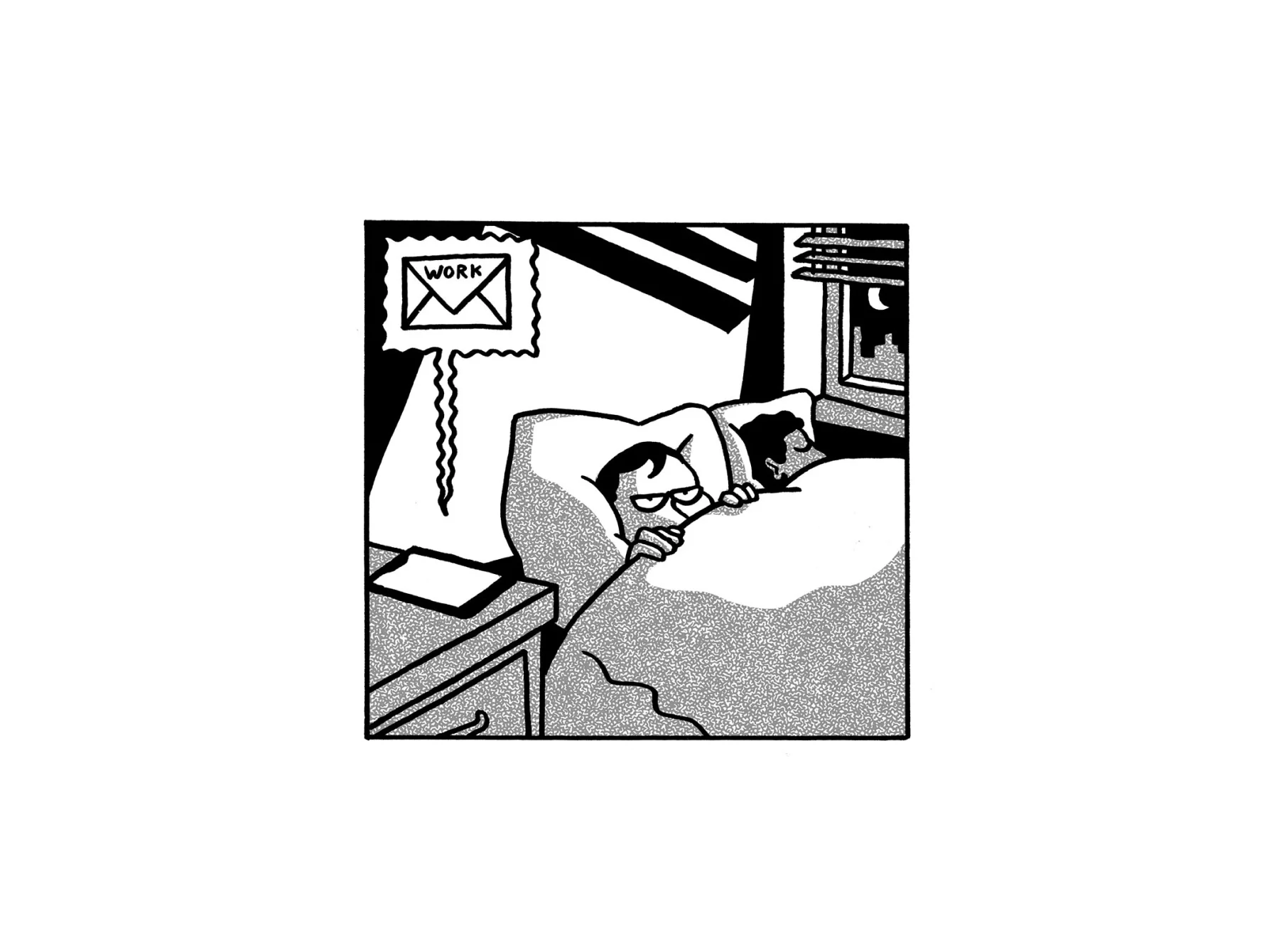

It is family lore that when my grandfather, a life-long accountant, was diagnosed with terminal cancer, he retreated to the home office of his Athens apartment and spent hours at his desk writing sums. When he died, my dad flew to Greece, opened my grandfather’s office door, and found hundreds of loose sheets of paper covering his desk and his chest of drawers and almost all of the floor. Each sheet was filled with simple equations, the kind you do in school, scrawled. When my dad returned home after the funeral, he explained what he’d discovered. Amidst terror, my grandfather had taken comfort in definite answers, in being right. Sums had offered escape from the terrible not-knowing. At least in his office, he had been able to sweep away a dark fog of incomprehension.

Sometimes, I wish I could do the same.