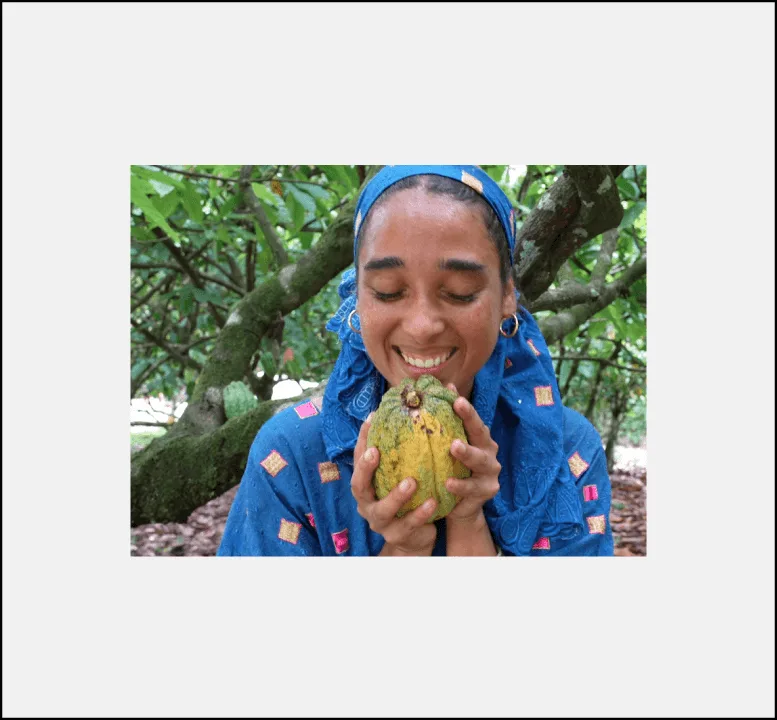

After years spent at the cutting edge of the digital art scenes in London and South Africa, Tabita Rezaire escaped to the Amazon rainforest in search of herself. In between cacao farming and full moon night walks, she tells Ravi Ghosh about family, spirituality, and birthing the project of a lifetime for Serpentine’s Back to Earth.

Tabita Rezaire is raising funds for Amakaba, a healing and educational centre for the wisdom of the earth, body and sky in the Amazonian Rainforest of French Guiana. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

In this age of constant video calling, the sight of a faux-tropical screen backdrop is commonplace – a final frontier for digital privacy, and a tongue-in-cheek nod to an improbable escape from lockdown life. But when speaking with Tabita Rezaire, reality replaces illusion. The lush Amazonian rainforest of French Guiana sprawls behind her as she sits on a simple wooden porch, the scene a stark contrast from my dreary London, just a few miles from the Serpentine Gallery.

Tabita smiles as she prepares to tell the story of how she returned to her ancestral home. It’s a chapter of her life with many subplots and one in which the characters from her time as an artist in Paris, London and Johannesburg have been retired in favour of a deeper introspection. It is from this new worldview that Amakaba came into being, which the Serpentine is supporting as part of Back to Earth.

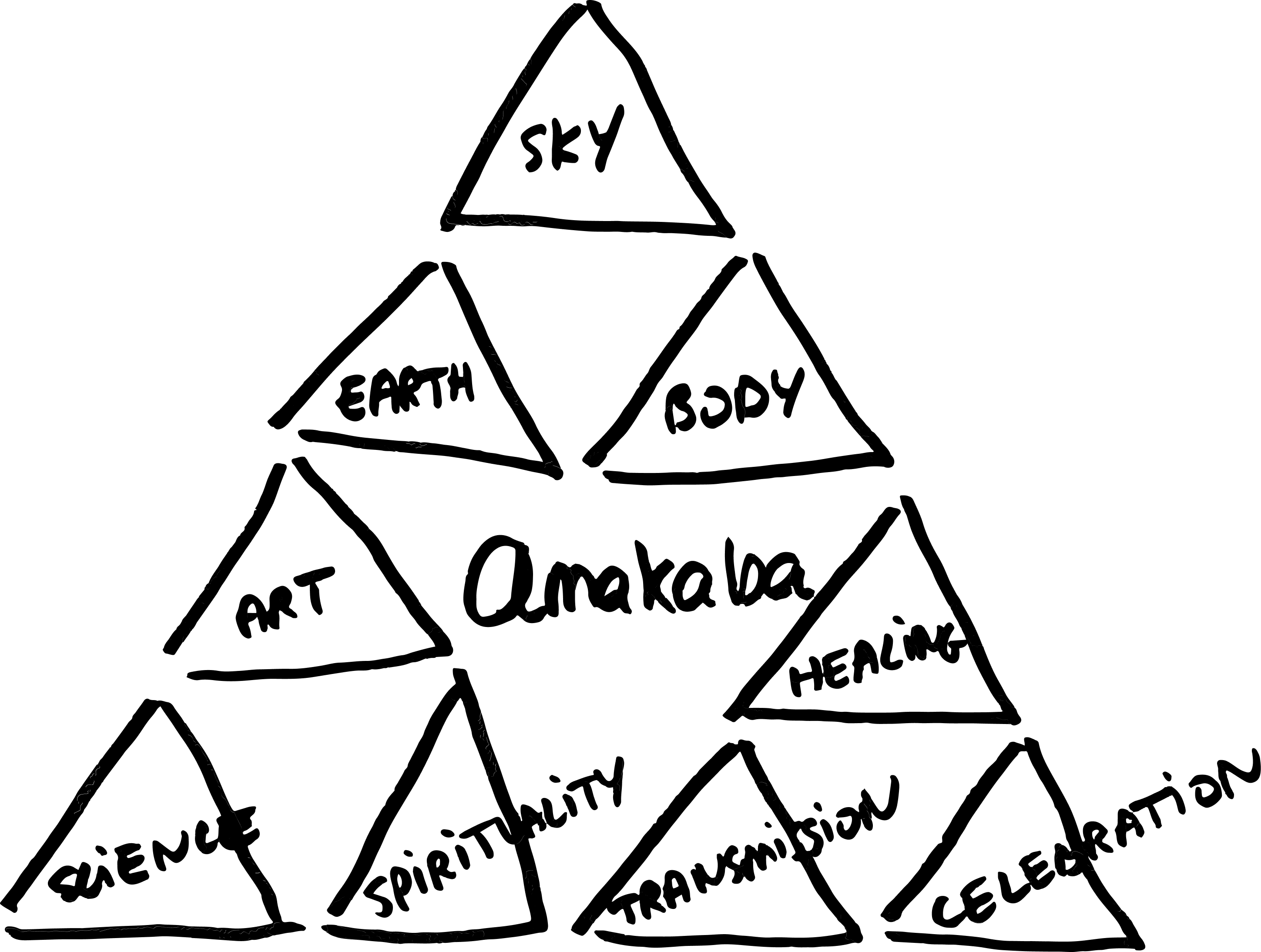

On the surface, it will be a center for the arts and science of the earth, the body and sky, with a farm and yoga center but it will also combine the spiritual and ancestral philosophy Tabita nurtured in South Africa, while acting as a spiritual anchor for land and ancestral healing.“It’s a vision for a space where one can connect with a journey into the depths of themselves, guided by the wisdom of the Amazonian forest,” Tabita tells me. “A place where one can grow and expand their perception and their intimacy with the land, the sky, and with themselves.”

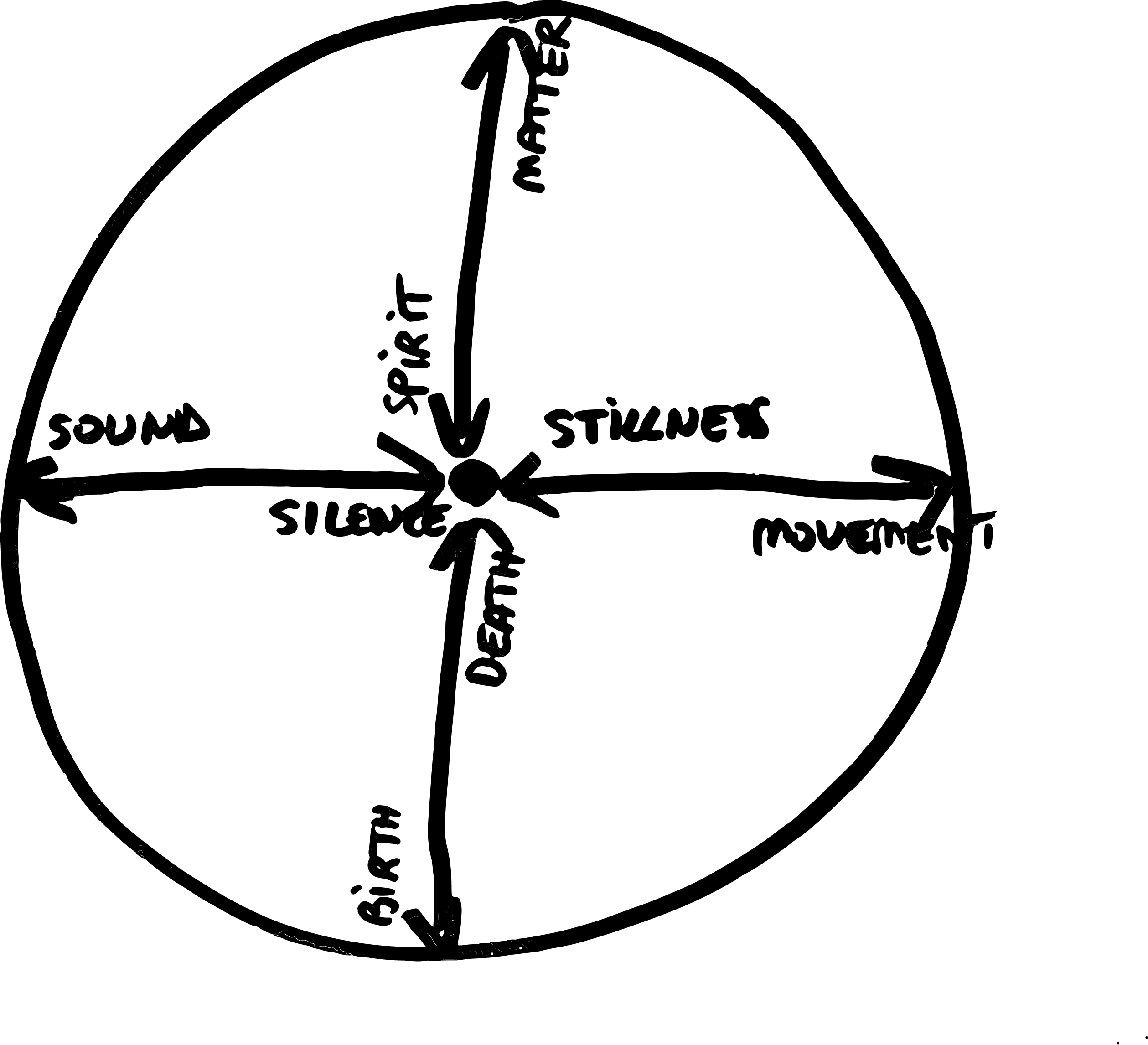

Alongside the emphasis on individuals’ relationships with their surroundings, pedagogy and group consciousness are essential to the project: Tabita takes inspiration from informal schooling, nature walks, ancestral technologies, indigenous governance, and spiritual centres when imagining the Amakaba of the future. “It’s very important for me that this space acknowledges different systems of knowing,” she explains. Earth, body and sky intersect with the fields of art, spirituality and science – “I’ve always got my telescope or physics books out,” she says – to give the project broad scope for expansion and enrichment.

Tabita is best known for her work as a pioneering internet artist tackling sex, pop, body politics, race and new media, describing herself as “infinity longing to experience itself.” Afro Cyber Resistance (2014) acts as an early manifesto where she embarks on an essayistic takedown of internet colonialism, beginning with the question: “There is no geographical border on the internet, but does it really not matter where you come from online?” She then destabilises the idea that the internet is a level playing field: why is it that there is so little factual information about the African continent on online encyclopedias? Digital democracy is a myth, and the concentration of resources on the West and Global North encourages dissent and anti-establishment thinking. “History needs to be rewritten,” Tabita says in the video. “We address and we evaluate it, without the patriarchal, white, imperialist prism of supreme knowledge that is nowadays still prevalent.”

Healing has always been at the centre of Tabita’s practice, whether via organic, electronic or spiritual avenues. Her recent work Orbit Diapason (2021), a two-channel video installation draws inspiration from the stone circles of South Africa to investigate realms of alienhood, motherhood and invasion. Merkaba for the Hoeteps (2016) harnessed the power of Kemetic yoga, while her ongoing SYGYZY takes the form of a stargazing evening encouraging participants to meditate on the same trio of forces employed in Amakaba: art, spirituality, science.

Is it right to see Amakaba simply as an extension of her practice? The answer is complex. "It's almost as if my art was the base for this vision and all the things I have been talking about are now about to be lived out and put into practice in Amakaba," Tabita says. Living in Johannesburg, she began to consider buying land to break the constraints of the art world and expand her practice beyond “digital memory, to ancestral memory.” Despite having a settled spiritual and artistic community in South Africa, she initially decided to return to her father’s native French Guiana for a year, but has now been there for three.

“As much as I’ve been blessed by the art world and I’m very grateful for it – the things I’ve learnt, the travel, and the privilege to live off it – it’s also been rough,” she says. “I came to Amakaba in order to release myself from the pressure and anxiety of working in the art industry, so there’s a part of me that is afraid that it becomes an artwork.” The project’s healing potential is contingent on her resolving these tensions – healing that starts with the self. “I felt so mistreated by the art world. But I’m realising now that I was the one mistreating myself. Self-respect and honouring one’s rhythm are not easy things to do, but I’m learning.” For the first two and a half years of her time in French Guiana, Tabita stayed with her whole extended family in a single living compound (her father is one of nine siblings). It was a culture shock for someone accustomed to living an independent, free life in cosmopolitan cities around the world.

Self-respect and honouring one’s rhythm are not easy things to do, but I’m learning.

The experience epitomised the transformation that Amakaba represents: diving inwards and unearthing ancestral wisdom. Taking the rejection of Western norms that Tabita championed in her artwork, and actualising them in her everyday life – a process of unlearning the past and accepting a more interdependent existence. “I’ve spent the last 10 years criticising hierarchy in all its forms: between people, between gender, between systems of knowledge,” she says, “and here I was faced with a hierarchy of generations that I could not understand… At first I didn’t have the humility to understand the beauty behind that obedience, but now I see the profound beauty of honoring the elders. You need a humility that I do not think I had growing up in the West. You have to obey because there’s something greater than you. Your desires and needs sometimes have to be put aside for the needs of the community. It’s there that I really understood what it takes to be in community.”

A source of continued tension is the preservation of the Amazon rainforest. Although between 95 and 99% of the country is covered by forest, a complex European colonial legacy puts it at the centre of disputes between indigenous and multinationals seeking to extract gold and other resources.

I literally see Amakaba as a womb that you can go into in order to be rebirthed – to cleanse.

The collective trauma of working the land during times of slavery haunts some communities, leaving a deep suspicion of farming and living in the Amazon. Other indigenous and maroon populations maintain a deep spiritual relationship with the forest, still living in small communes under customary law. “When I moved here, my whole family said: ‘why are you going to live in the forest? It’s dangerous. People don’t do this,’” Tabita explains, before laughing that “it’s mostly white people who come and are interested in biodiversity and ecology.” Amakaba is an invitation to develop intimacy with the forest in the hope of uncovering a newfound harmony. “My vision for Amakaba is being rooted in the forest,” Tabita says, “to honour that we are people of the forest and to reconnect with its guidance.”

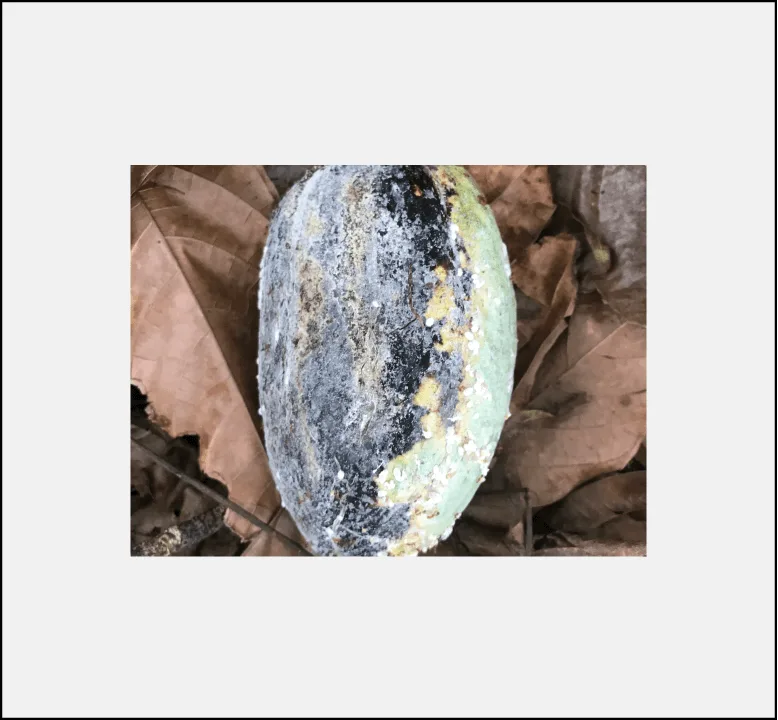

When we speak, Tabita has just started her agricultural studies, spending whole mornings on a tractor. She plans to grow cacao, as the plant has been calling her for some years and led her journey into farming. Beyond recalibrating French Guianese associations of farming beyond slavery and healing our relationship with the land and its histories, Tabita also hopes to practice sustainable land treatment, in the wake of mass deforestation across South America. And while this cause is urgent, there is also a value in patience: it will take three years for her first cacao pod to be harvestable.

Ideas of nurturing and cultivation extend to Tabita’s interest in birthing (she often uses the idea of birthing, rather than creating, her projects). “A lot of my work has been about womb wisdom and the feminine energy or feminine power,” she says: “the spiritual agency of the womb and womb-holders is profound. We need to heal the trauma that we carry in our wombs.” Training as a doula is a long-held ambition, following in the footsteps of her grandmother after whom the midwifery unit at a local hospital is named. Tabita hopes that Amakaba will one day host its own birthing centre. “I literally see Amakaba as a womb that you can go into in order to be rebirthed – to cleanse.”

I felt so mistreated by the art world. But I’m realising now that I was the one mistreating myself.

Amakaba will eventually be a space of mutual benefit for international arrivals and local people. Tabita is not naive to the realities of a globalised world, nor the complexity of creating authentic spiritual experiences. In so many of Amakaba’s dynamics, she herself is the bridge between these worlds, whether cultural, ancestral, or artistic. Just as she eventually came to embrace her family’s way of living, her detachment from the art world is far from concrete, instead a current state always subject to reform and growth.

The breadth and ambition of the project can obscure the serenity that underpins it; it is, ultimately, about healing and being one with self and surroundings. “You don’t have to produce anything at Amakaba,” she says, “it’s not an art space; it’s not a residency. It’s just about coming and talking to the trees for some time. It’s different experiences of living and being in the forest; and just being in the forest is transformative.”

Explore more

A

Amakaba, The Moon Center. Website, Tabita Rezaire, 2021.

D

Debra Pascali-Bonaro, Orgasmic Birth: The Best-Kept Secret.. Documentary Film, 2009.

G

Global Oneness Project, Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa: A Message to the World. Video. YouTube, posted on May 10, 2008.

J

Japan Experience, Shinrin-Yoku: Forest bathing. Article, June 15, 2020.

S

Sadhguru, Vanaprastha: Becoming Conscious of Your Mortality. Article, Isha Foundation.

Sen. René Oscar Martínez Callahuanca, Law of the rights of Mother Earth. PDF, Bolivia, July 12, 2010.

T

Tabita Rezaire, Womb Ecology _ Decolonial Birth. Article. Decolonising Design, Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2021.

Groundwork is a collaboration between the Serpentine and WePresent. It explores the extensive research behind five artists’ proposals for Back To Earth, Serpentine’s multi-year project focused on instigating change in response to the climate crisis.

Groundwork will act as a series of accessible mini-encyclopaedias with all the references artists use to develop a final artwork. They will go behind-the-scenes on the research the artists have done as part of their project for Back to Earth, in a bid to reveal their processes and inform how the viewer might see the project as a whole when completed. It will involve diving deep into the research of artists such as Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Vivienne Westwood, Karrabing Film Collective, Himali Singh Soin and Tabita Rezaire.

Tabita Rezaire is raising funds for Amakaba, a healing and educational centre for the wisdom of the earth, body and sky in the Amazonian Rainforest of French Guiana. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

Back to Earth is curated and produced by Rebecca Lewin, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jo Paton, Lucia Pietroiusti, Holly Shuttleworth and Kostas Stasinopoulos.