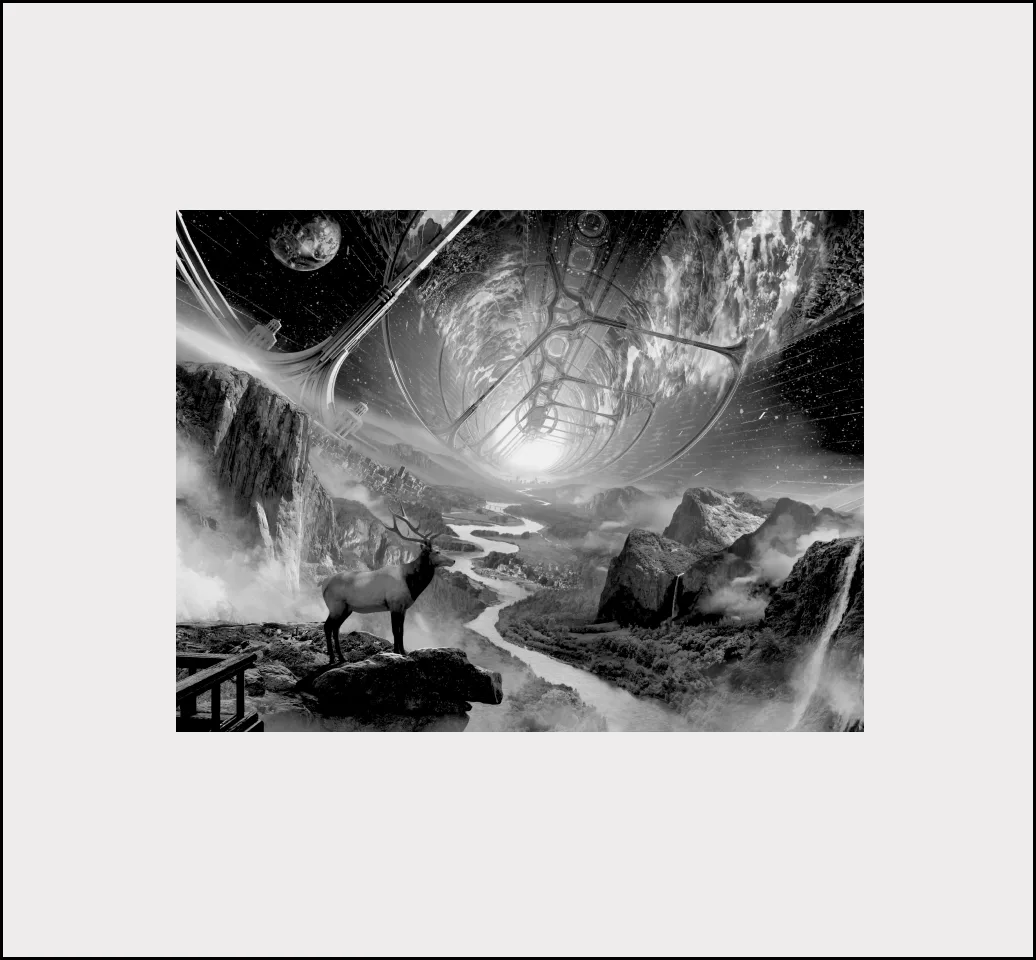

Virus-loaded meteors, space colonies, and the inner life of octopuses: for the first in WePresent’s Groundwork collaboration with the Serpentine, Ravi Ghosh explores the influences and ideas behind Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen’s Heavens, an immersive installation created for Back to Earth.

Trigger warning: this article contains flashing imagery

Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen have chosen to highlight the Climate Emergency Fund to support them in funding frontline climate activists campaigning for policy-makers to take radical action. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

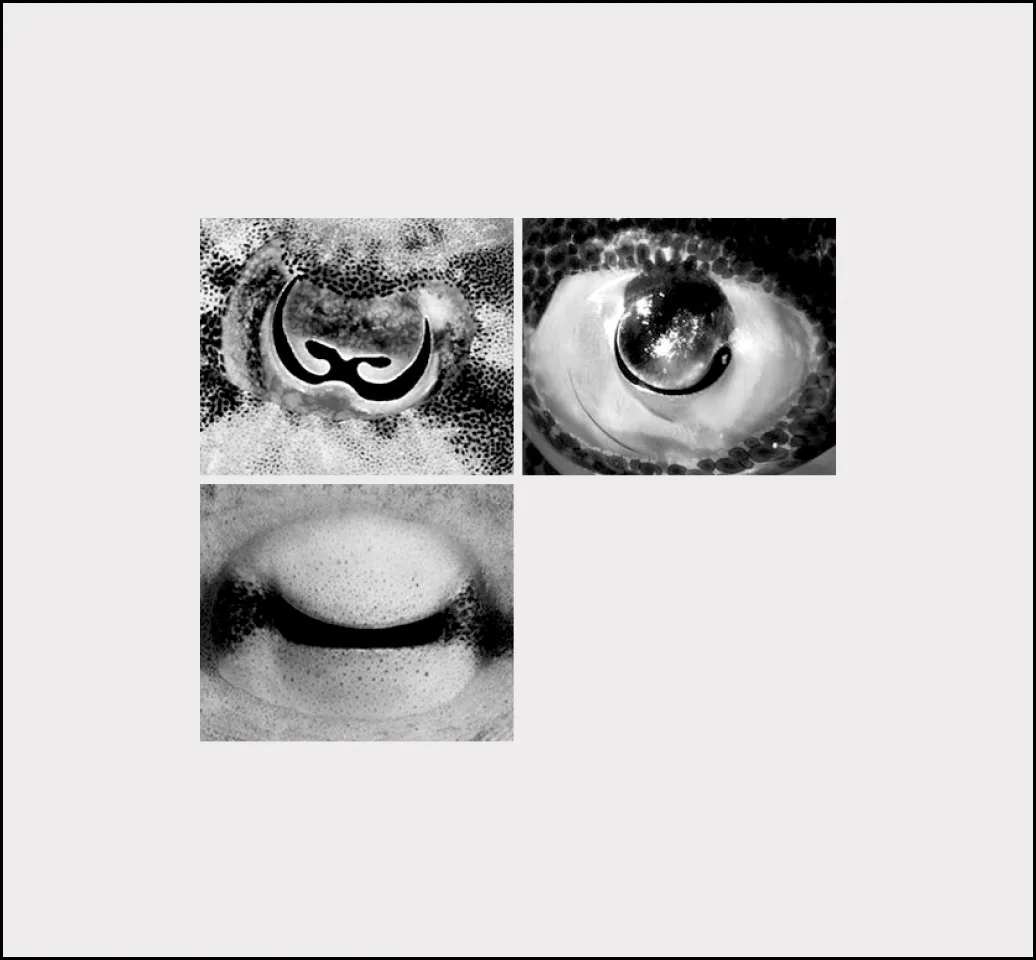

When octopuses feature in the news, it’s usually worth paying attention. Between 2008 and 2010, a common octopus named Paul received worldwide fame by correctly predicting a string of international football results, including all seven of Germany’s matches at the 2010 World Cup and, eventually, the tournament’s winner. In 2016, another octopus made headlines after escaping from its enclosure in New Zealand’s national aquarium and navigating its way to the sea. These two stories capture the creature’s essence rather well: smart and slippery. Octopuses are at the forefront of research into non-human consciousness, an area of increasing interest given the rapid developments in artificial intelligence. As humans grapple with the ethics of advanced computing, why not look again at Earth’s own varieties of non-human cognition?

Artists Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen are just two of those from a diverse array of fields asking this question. Working across objects, installation and film, the pair often explore the constructed nature of the world around us and its organisms: interrogating the boundaries between the natural and artificial. In Sterile (2014), they engineered 45 albino goldfish to hatch without reproductive organs. Can fish still be considered animals if they cannot procreate? And what happens when genetic manipulation becomes fundamental to a species’ very existence? Think thoroughbred racehorses, which also feature prominently in the duo’s work. “We often think of the body of the animal as an object,” says Tuur Van Balen. “As something designed and produced.”

It was Australian philosopher (and keen deep sea diver) Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (2016) that prompted the pair to consider the octopus in this way. One line in particular from the latter stood out to Revital & Tuur. The octopus, Godfrey-Smith claims, “is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.” Amia Srinivasan, a professor of social and political theory at Oxford, later captured this otherness in an essay on Other Minds.

We often think of the body of the animal as an object. As something designed and produced.

“Octopuses – and to some extent their cephalopod cousins, cuttlefish and squid – frustrate the neat evolutionary division between clever vertebrates and simple-minded invertebrates,” she wrote. “They are sophisticated problem solvers; they learn, and can use tools; and they show a capacity for mimicry, deception and, some think, humor.” This fascinated Revital & Tuur.

The pair’s practice focuses on the systems which enable everything in the world around us – from humans to precious metals, oil, and even ideas – to exist as they do.

All entities sit within a structure, and the forces that govern and reproduce these structures can always be interpreted through art. Thoroughbred racehorses, for example, “can only exist within the ecology and economy of gambling,” Van Balen explains. The world of gambling gives the animals – and those who modify, train and ride them – a continued incentive, just as it does casinos and other competitive sports. In their video The Odds (Part 1) (2019), Cohen & Van Balen use slow footage of slow footage of casino showgirls, anaesthetized racehorses and a grade 2 listed bingo hall. A bright, ambient soundscape hums while the horses gradually collapse to the ground as the sedative takes effect.

But it was another facet of gambling which would guide the pair as they began researching for Heavens. Seasoned gamblers never believe they are losing; only that they are on the cusp of a big win, warping reality’s laws to suit their own desires. “There’s a term we’ve been using in our work a lot over the last two years: apophenia,” explains Cohen: “where one sees patterns where perhaps they don’t exist.” By applying this logic to octopuses, the pair have widened their scope beyond the scientific, towards the spiritual and philosophical dimensions of non-human intelligence.

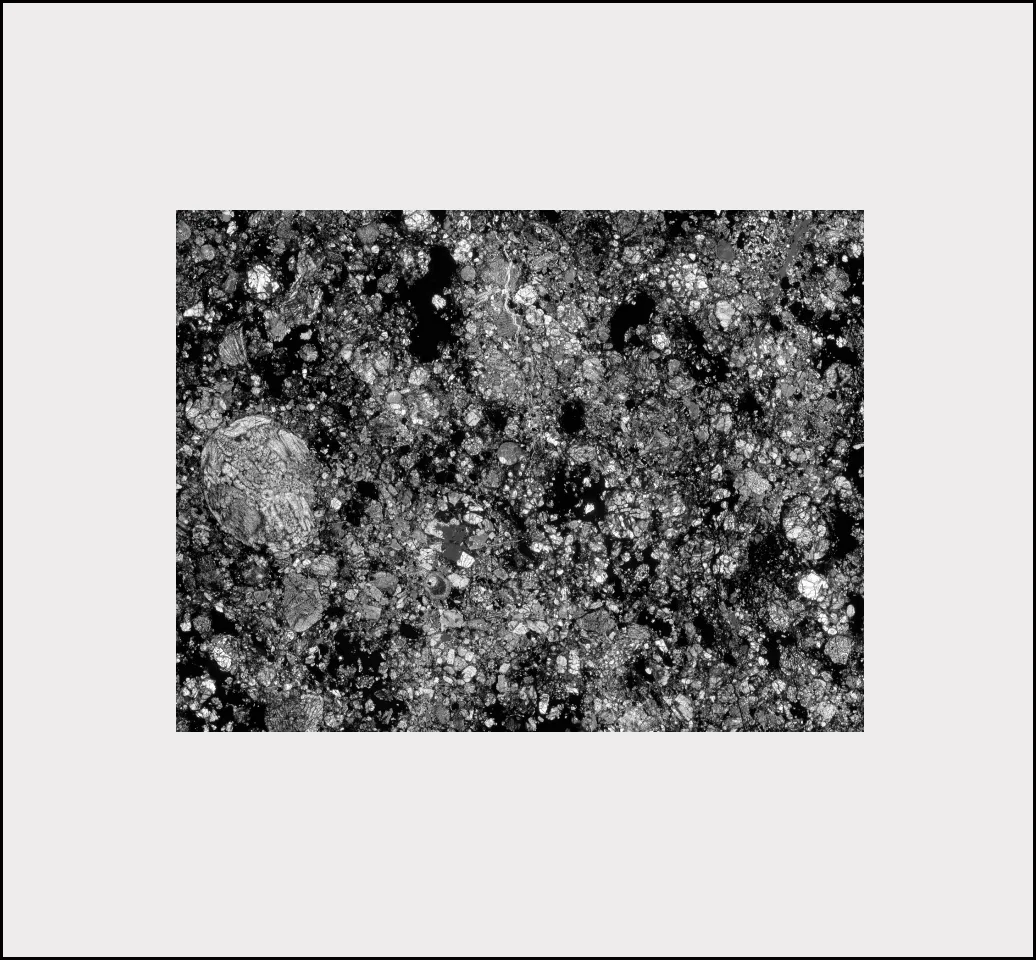

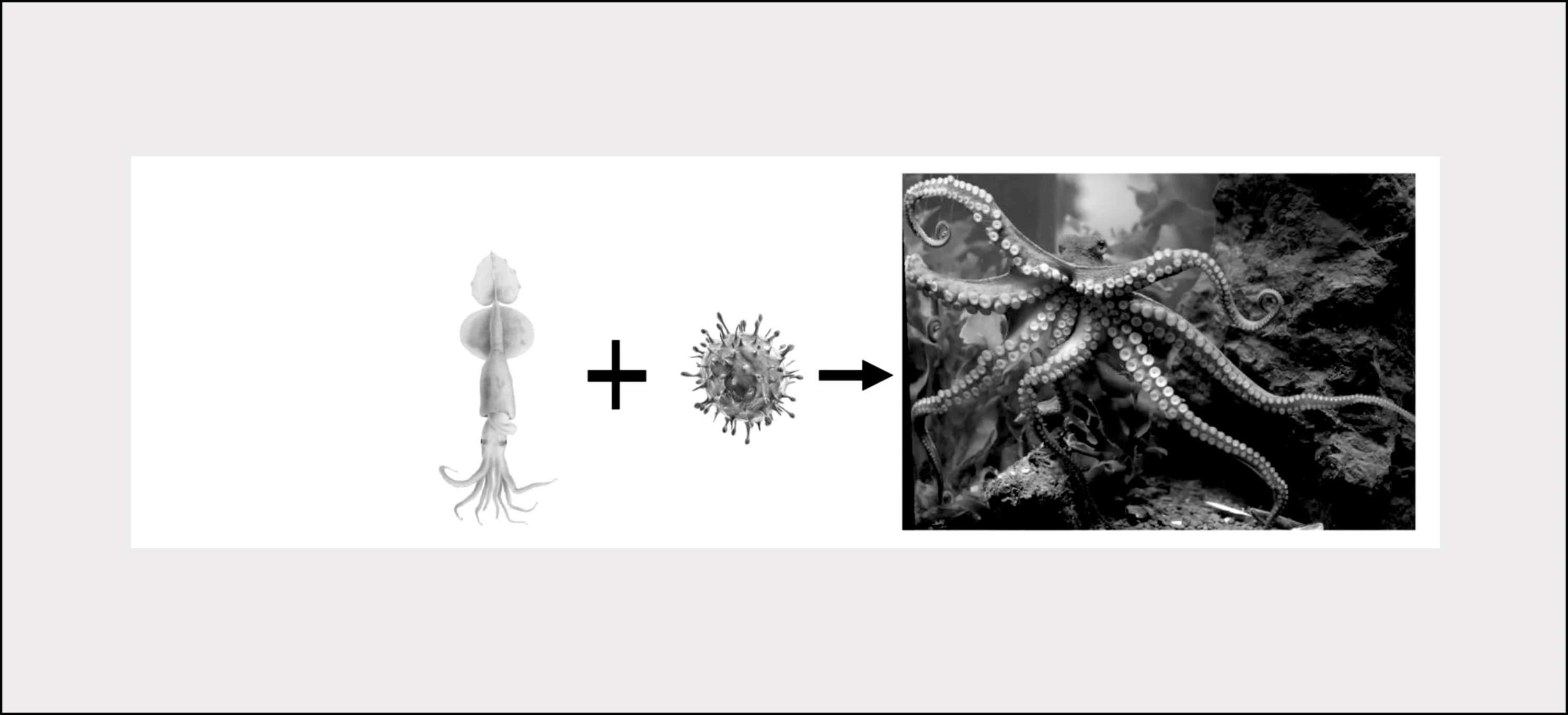

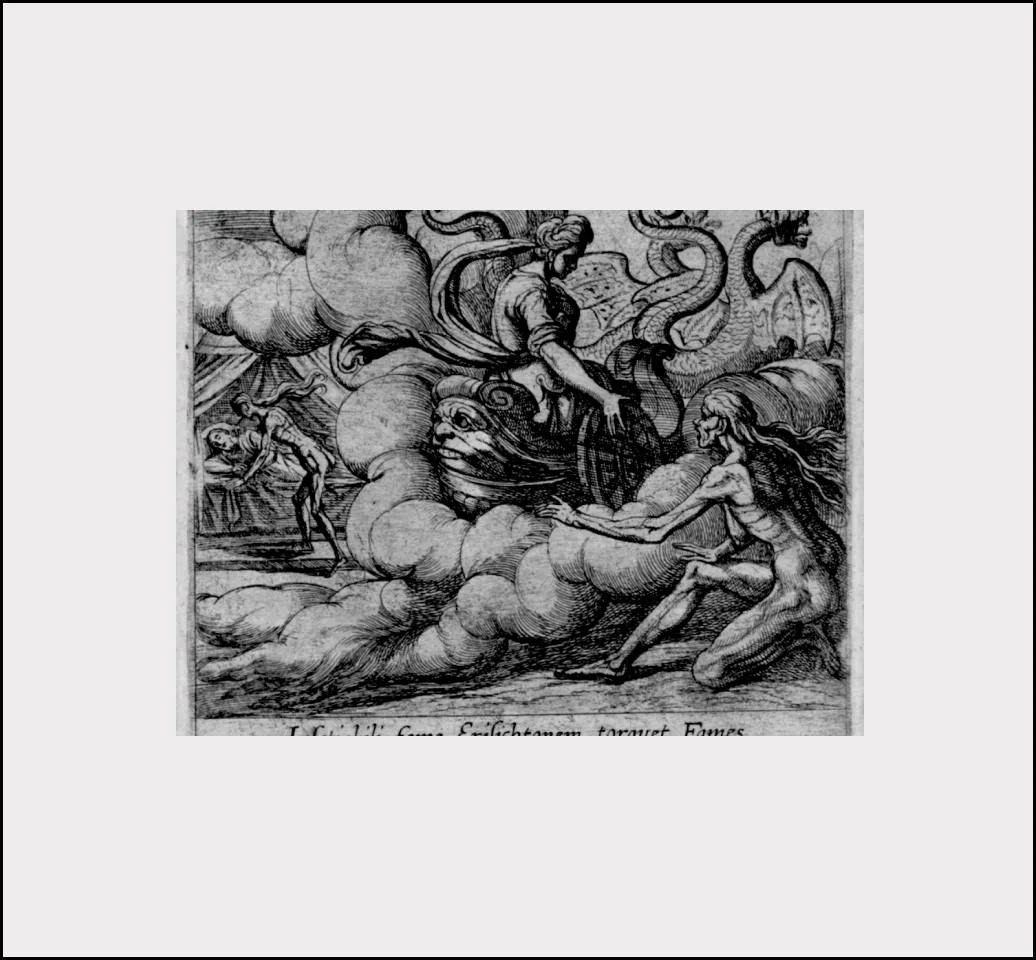

These overlapping spheres are epitomised by The Cause of Cambrian Explosion – Terrestrial or Cosmic?, a biophysics study which notes that evolutionary changes recorded in ancient fossils

during Earth’s Cambrian period (roughly 541 million years ago) coincide with “virus-bearing cometary events.” The scientists bring forward a simple but outlandish proposal: that “life may have been seeded here on Earth by life-bearing comets.”

Could it be true? The theory is heavily contested in the scientific community. “But we’re not talking flat earth here,” laughs Van Balen. Its truth is less important than its potential as a starting point for their imagination – and their art. “For us, it had the same effect as looking at the stars,” reflects Cohen: “a thought that makes the boundaries in your head dissolve, that we are more connected to other planets, and that earth’s species are part of a bigger system...The octopus’ escape artistry got me thinking about space as an escape strategy: SpaceX and Blue Origin,” Cohen continues.

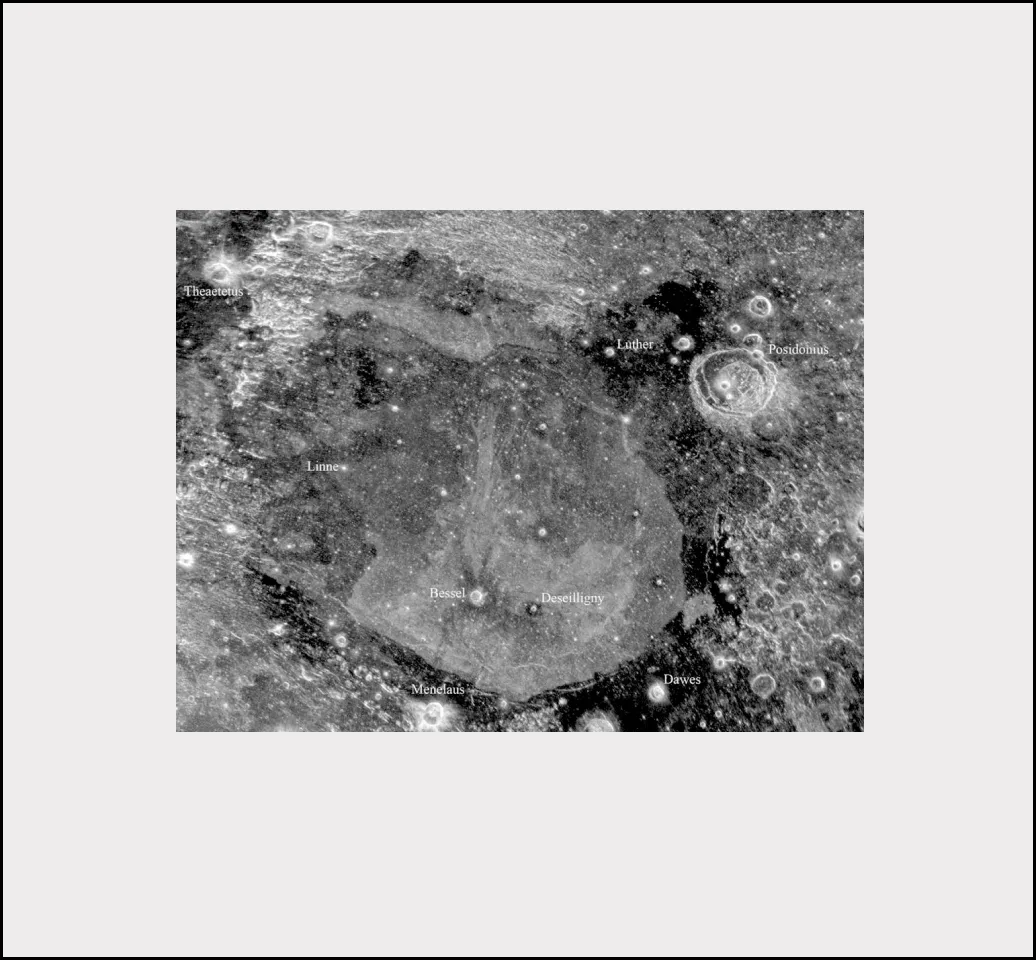

In 1913, Oskar von Miller, founder of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, commissioned optician Carl Zeiss to create a device capable of projecting images of stars and planets onto a dome. After 10 years of research, the projection planetarium was born. In 1928, philosopher Walter Benjamin expressed his worry about these new technologies in his essay To the Planetarium. Benjamin argued that scientific progress was diminishing the sense of wonder that humanity felt towards life beyond this planet, hailing past generations’ relationship with outer space as an “ecstatic trance.” Before the sky became a place of research and education, it was a site of spirituality and the magic of the unknown – the loss of which was feared by Benjamin. Stargazing and astrology – reading shapes in the sky – are the original form of apophenia, say Cohen & Van Balen.

Both these episodes are referenced in Spots, Stars, Tunnel Vision, Cohen & Van Balen’s text for Heavens. Although decades apart, Benjamin and the authors of the Cause of the Cambrian Explosion both ask us to consider outer space like never before, often in defiance of scientific consensus. Together, Cohen & Van Balen write, these references “dissolve ideas of galactic boundaries and open new perceptions around evolution, the history and potential futures of species on this planet.” If, as the scientists argue, life may have come to earth from space during the Cambrian period, could it not do so again? To explore these ideas, Heavens will take the form of an immersive audiovisual work made using a planetarium projection – an alternative creation myth.

Despite its camouflaging capabilities, the octopus’ color blindness also raises questions around perception and agency.

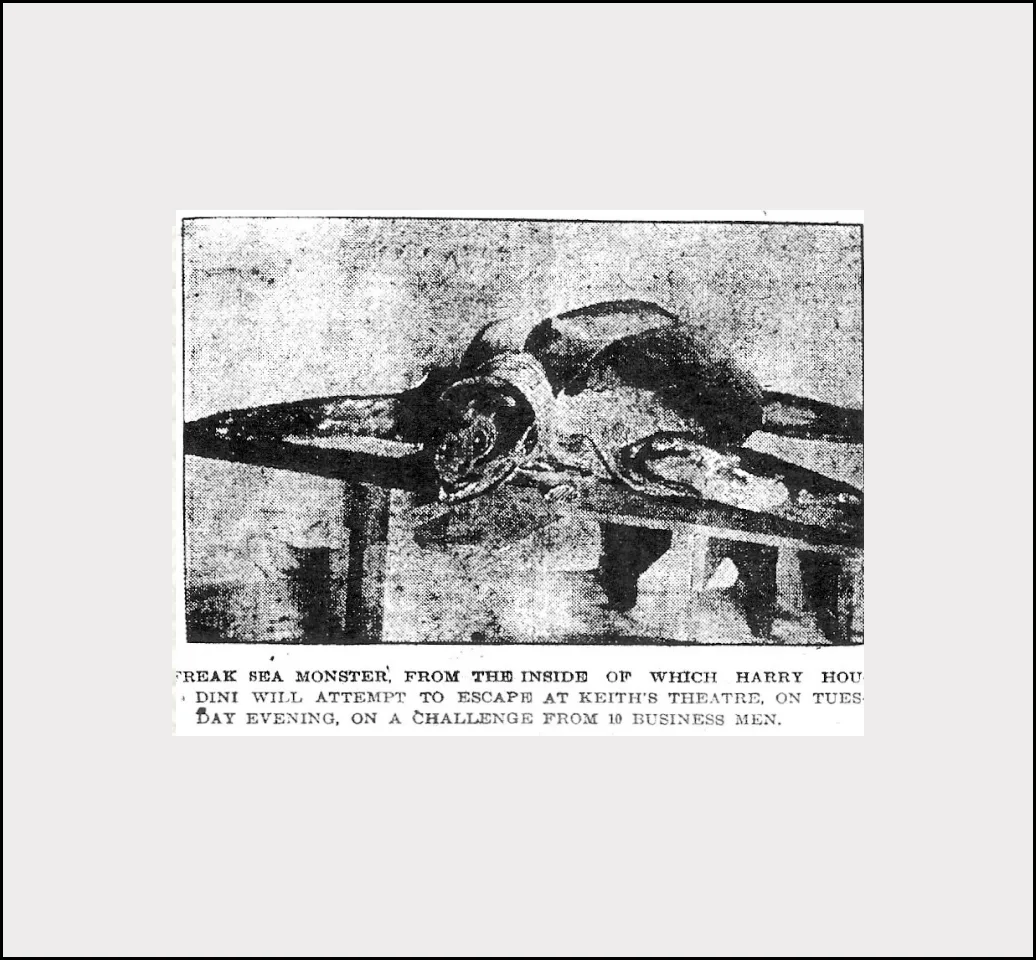

The project’s soundtrack will be inspired by octopus anatomy – one central brain and one in each of its eight arms – comprising conversations between the artists and eight thinkers. Using a cut-up method borrowed from the writer William S. Burroughs, the audience will hear a text composed of fragments from a philosopher, a sexologist, a marine scientist, an escape artist and others. “The conversations will follow cultural narratives and scientific observations inspired by octopuses’ behavior and anatomy,” the duo say: “complex mating strategies, self-cannibalism, erotic iconography, non-human engineering or rituals of an oracle.”

“We treated Amia Srinivasan as ‘patient zero’ or ‘brain one,’” Cohen explains. Cohen & Van Balen were keen to probe Amia on the idea that consciousness is non-binary: by moving away from the idea that creatures are either conscious in a human sense or not, animals like octopuses – with all their complex behaviors – could be better understood. “Part of the motivation for the all or nothing view is that it is difficult to imagine consciousness being possessed in degrees,” Srinivasan wrote in her LRB essay.

Heavens is all about exploring these spaces in between. Despite its camouflaging capabilities, the octopus’ color blindness also raises questions around perception and agency. “What does it mean for a creature to express color without being able to see it?” Cohen asks. Heavens is an opportunity to explore these paradoxes, not reach for definite answers.

Discussions with Edward Bloomer, planetarium astronomer at the Royal Museums Greenwich, have allowed Cohen & Van Balen to consider the spatial dynamics of the work; from Carl Zeiss’s era, astronomers have debated how to position audiences to create an authentic planetary experience. They have experimented with gifs, abstract animation, stock footage and Celestia, an open-source planetarium software – recalibrating it to allow foreign objects to shoot across the night sky. “There’s no offscreen in a planetarium,” Van Balenexplains, “only below the horizon.”

Religious ritual is an important inspiration for Heavens; the pair are keen to work with a choir and classical composer to complement Van Balen’s futuristic electronic music. He notes that like our crafting of animals, we have also formed moments of human collectivity, from raving to prayer. “We can think of them as evolved experiences and products.”

The octopus, Godfrey-Smith claims, is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.

The text continues: “We cannot meaningfully separate human and non-human systems in the messy global entanglement we live in – maybe we never could.” It’s a neat summary of Heavens’ influences and aims. Meaning will come not from its individual elements – the strangeness of the octopus, the escapism of the planetarium, the critique of technology – but their messy, blurred interrelation. Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen’s work asks its own questions rather than answering the audiences’. “We’re not interested in the rational,

didactic experience,” says Van Balen. “We’re much more interested in creating a form of cosmic trance.”

Explore more

B

Book of Revelation 6:12

William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, The Third Mind (1978)

William S. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded (1962)

L

Jean-François Lyotard, “Can Thought Go On Without a Body?”, Discourse (1988)

M

Alexis C. Madrigal, “The Blood Harvest”, The Atlantic (2014)

S

Amia Srinivasan, “What Have We Done to the Whale?”, New Yorker (2020)

W

Sarah Wild, “Are Viruses the New Frontier for Astrobiology?”, Astrobiology Magazine (2018)

Groundwork is a collaboration between the Serpentine and WePresent. It explores the extensive research behind five artists’ proposals for Back To Earth, Serpentine’s multi-year project focused on instigating change in response to the climate crisis.

Groundwork will act as a series of accessible mini-encyclopaedias with all the references artists use to develop a final artwork. They will go behind-the-scenes on the research the artists have done as part of their project for Back to Earth, in a bid to reveal their processes and inform how the viewer might see the project as a whole when completed. It will involve diving deep into the research of artists such as Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Vivienne Westwood, Karrabing Film Collective, Himali Singh Soin and Tabita Rezaire.

As part of their project and dedication to making a positive impact regarding the climate crisis, Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen have chosen to highlight the Climate Emergency Fund (CEF). In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause. CEF will give 100% of the funds to frontline climate activists campaigning for policy-makers to take radical action.

Back to Earth is curated and produced by Rebecca Lewin, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jo Paton, Lucia Pietroiusti, Holly Shuttleworth and Kostas Stasinopoulos.