Mr. Wash — The artist on his paintings made during 21 years behind bars

The artist on his paintings made during 21 years behind bars

Sentenced to life in prison for a minor drug offence, Fulton Leroy Washington turned to painting as a means of expressing himself during his 21 years behind bars. Then, thanks to Barack Obama, he was free. Gabrielle Bruney tells the incredible story of Mr Wash, and the filmmakers who brought it to life.

Sometimes you come across a story that just won’t let you go. For Marisa Aveling, it came from an article she wrote for The Outline profiling prisoners freed by Barack Obama in his final week in office.

Though each case offered a rending portrait of the failures of the US criminal justice system, Marisa knew there was more to the story of one of her subjects. So with director Sean Mattison, she set out to make a short film about Fulton Leroy Washington, aka Mr Wash, who created hundreds of paintings over the course of 21 years behind bars.

Mr. Wash is set amid the palm trees and tidy bungalows of Wash’s native Compton, but the film sits against a national backdrop of mass incarceration. The US has the world’s highest imprisonment rate; 17,000 Americans are serving life sentences for non-violent crimes, casualties of a war on drugs that destroyed countless lives to little positive effect.

These issues have been well recorded in documentaries like Ava DuVernay’s The 13th and Eugene Jarecki’s The House I Live In, so Marisa and Sean focused their film on Wash as an artist reckoning with years of imprisonment, not as a former prisoner who happens to paint.

Despite the nightmare of his two decades in federal custody – accused of a non-violent drug crime, assured of his innocence and sentenced to die in prison under draconian drugs laws – Wash’s creative skill is the film’s impelling peculiarity. His circumstances are ordinary, his talent is not.

Wash wasn’t an artist in his pre-prison life, but a contractor and welder. He had a knack for art since childhood though, and he was that much-envied elementary schooler whose every artistic effort was mounted in the school hallway.

Even then, he remembers seeing things differently from the other kids. In kindergarten, his teacher instructed the class to paint trees.

“Everybody was painting trees that looked like ice cream cones to me,” he says. "Just a green puff on top of a brown stick with no branches or leaves.” In copying the teacher’s example, his classmates painted with cultural eyes, shared by their instructor, parents and peers. Wash wanted to see more, and painted branches and fruit – the apples of his Aunt Emma’s orchard.

His prison life was bookended by works aimed at securing his freedom. The first was a sketch of an alibi who could confirm he was miles away from the scene of the crime he stood accused of committing. It was realistic enough that his defense team actually found the witness, who corroborated Wash in court.

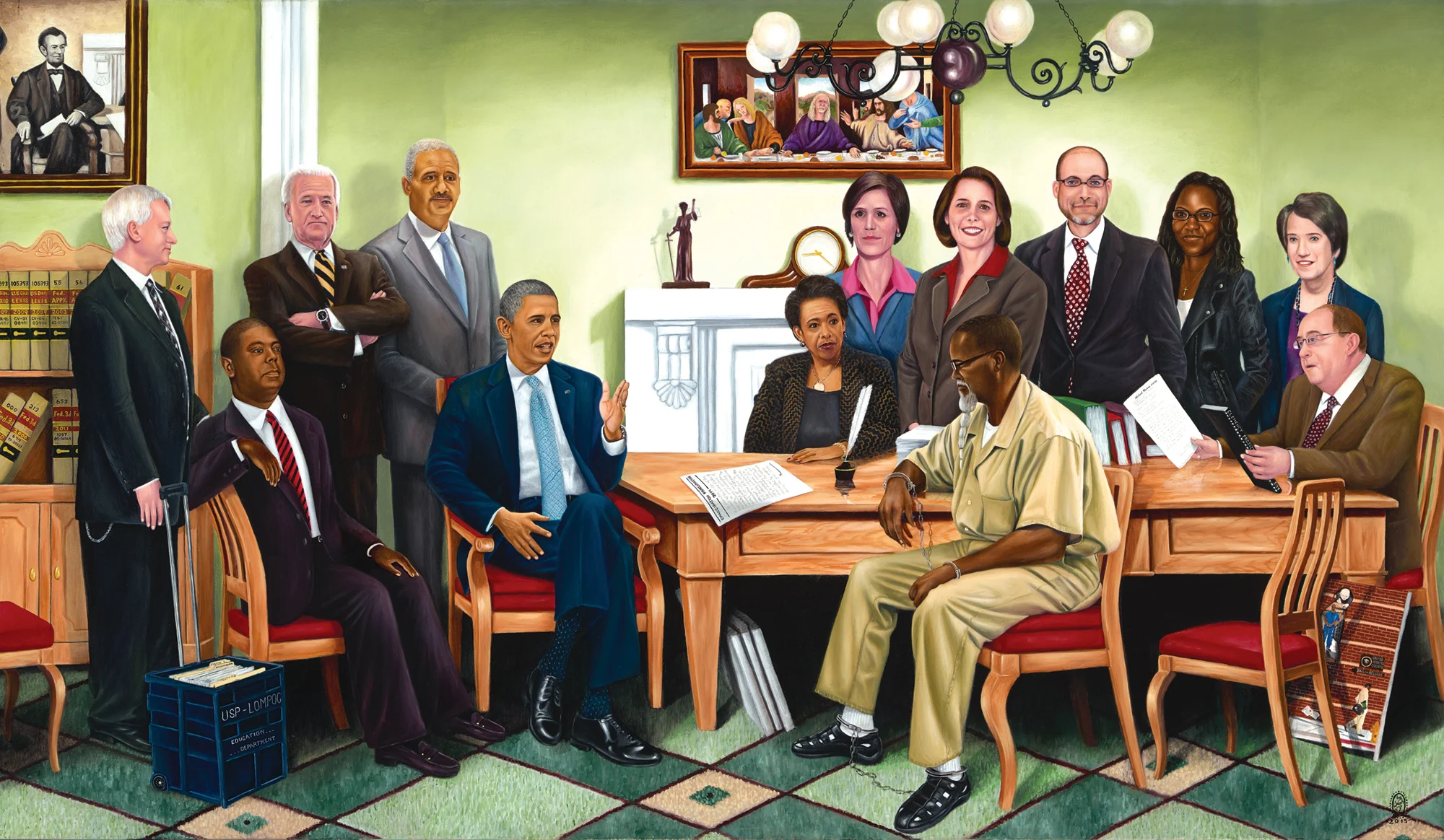

The second was Emancipation Proclamation, his take on Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln. In Wash’s adaptation, President Obama, surrounded by government officials, replaces Lincoln, and the emancipated are not absent slaves but Wash himself, shackled front and center in his prison khaki.

Listen to Mr. Wash and his lawyer on his case

00:50

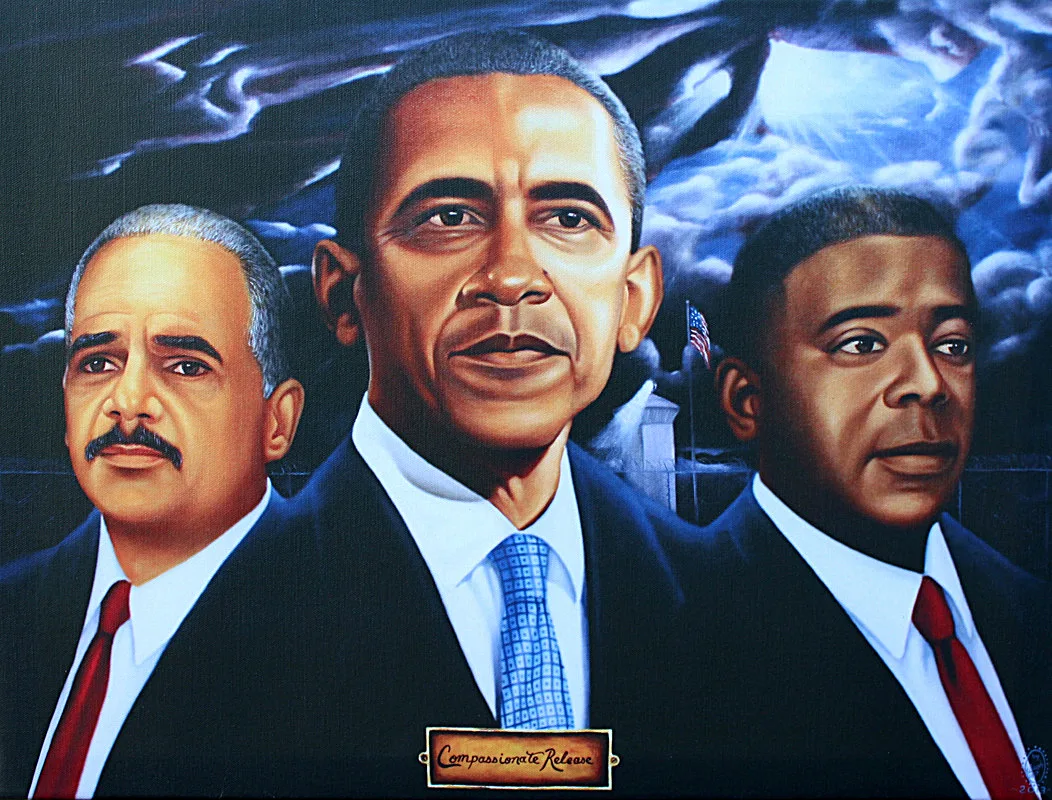

But he also used art to pursue less tangible goals. He first began painting in oils at Leavenworth, a federal prison where steel studs of long-ago gallows were still visible in the ground. His work served as a form of communication, as well as a way to win respect within a hierarchical prison society.

“Prison has a lot of politics,” Wash says. “Art was a neutral zone and a way to express the human emotions that both I and the other inmates were feeling.” Through painting he could bridge a prison’s often segregated population, accepting commissions for portraits of missed family members based on well-loved photos. An artist could be respected by inmates and prison officials alike – once, after a guard was murdered, Wash was enlisted to paint a picture for his funeral.

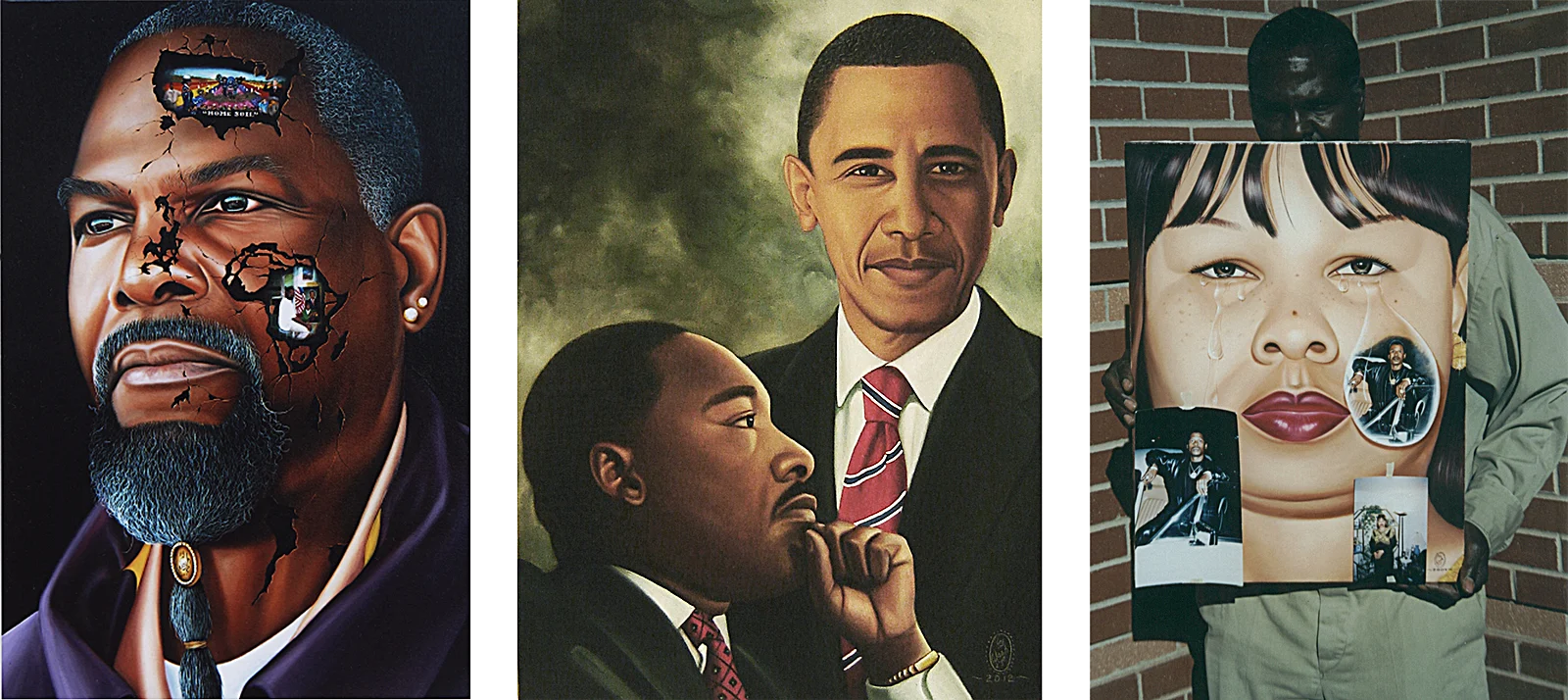

His oeuvre spans more than 900 works and ranges widely, resisting easy characterization. Wash's teardrop series consists of close-up portraits of public figures, politicians and prisoners, all weeping fat tears filled with moments of regret or longed-for loved ones.

Other paintings, like the one in which a freed man walks before a brick wall with the specter of his incarceration trailing in his shadow, contain surreal fables that suggest Norman Rockwell on a spectacularly trippy day.

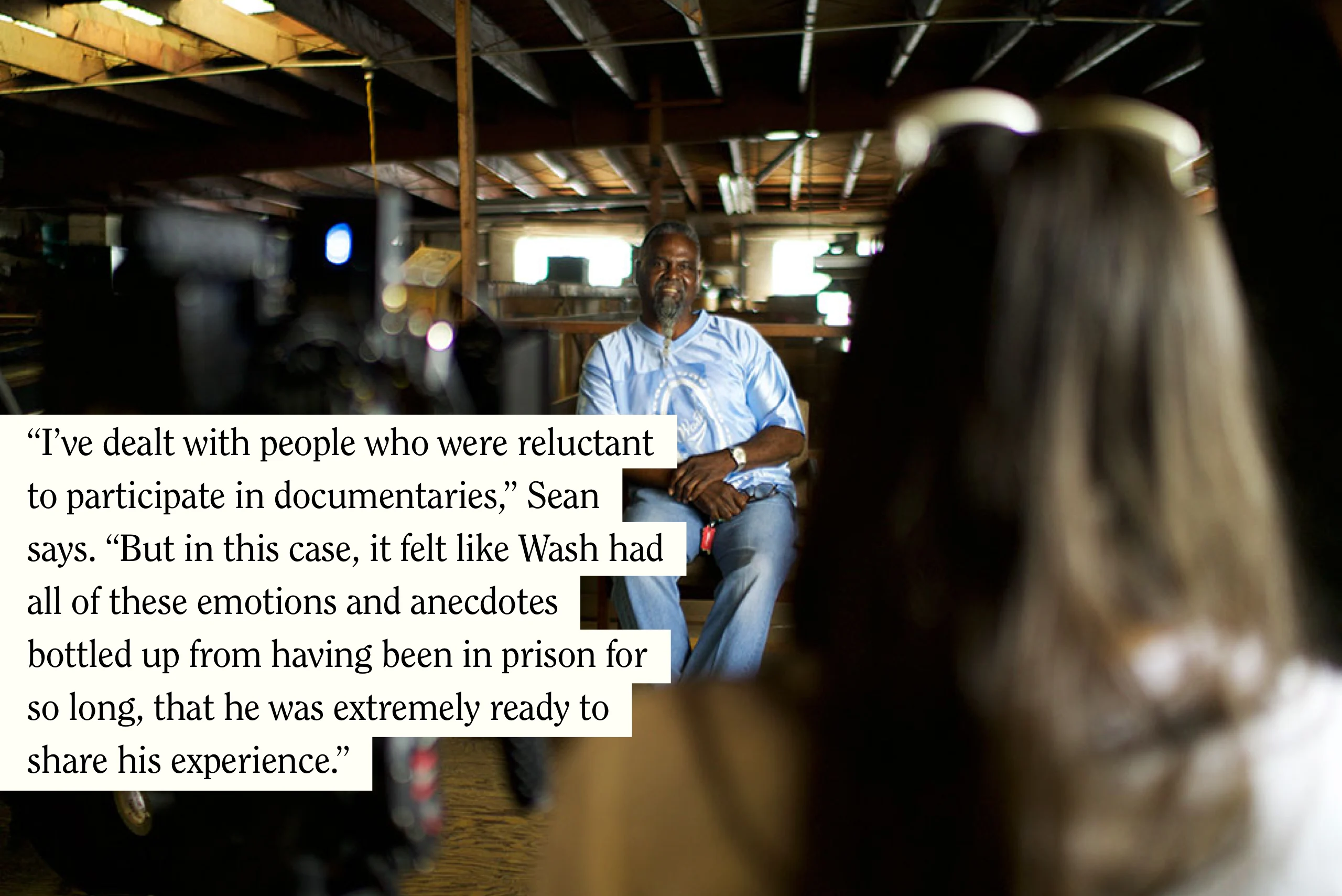

In Mr. Wash, Marisa and Sean created a film about the man that’s just as intimate as his art, resisting the standard documentary talking heads and archival footage rundowns.

“We discussed this reluctance to have it feel like we were interviewing people who were talking to an omniscient, off-camera narrator,” Sean says. Instead, the film is formatted around a series of conversations between Wash and his friends, family members and even his barber.

They present a view of Wash that underscores his connection with friends and loved ones, making us feel part of his community rather than observers of it. They couldn’t have hoped for a more inviting subject.

“I’ve dealt with people who were reluctant to participate in documentaries,” Sean says. “But in this case, it felt like Wash had all of these emotions and anecdotes bottled up from having been in prison for so long, that he was extremely ready to share his experience.”

Before they even met, there were months of daily phone conversations – Marisa jokes that she talks to Wash more than she does to her own parents.

To achieve the film’s remarkable intimacy, the New York-based pair then travelled to LA and spent hours talking to him before ever introducing a camera. “He was just so open, and extremely giving of his time and emotions,” Marisa says.

The goal was to make a film that was collaborative, not exploitative. “There’s this danger of extractive storytelling, where people just come in and do the quick thing, and we really wanted it to feel deeper than that,” Sean says. Marisa agrees – “I don’t think the film would have been the same had it been a parachute-in-and-then-drop-out thing.”

For Wash, filming the documentary was a chance to learn about yet another art form. “It was exciting and very educational to see how everybody in the production crew operates,” he says. “The sound, the lighting, waiting for the right time of day, atmosphere.” He played an active part, wrangling friends, family and filming locations, and he’s credited as one of the film’s co-producers.

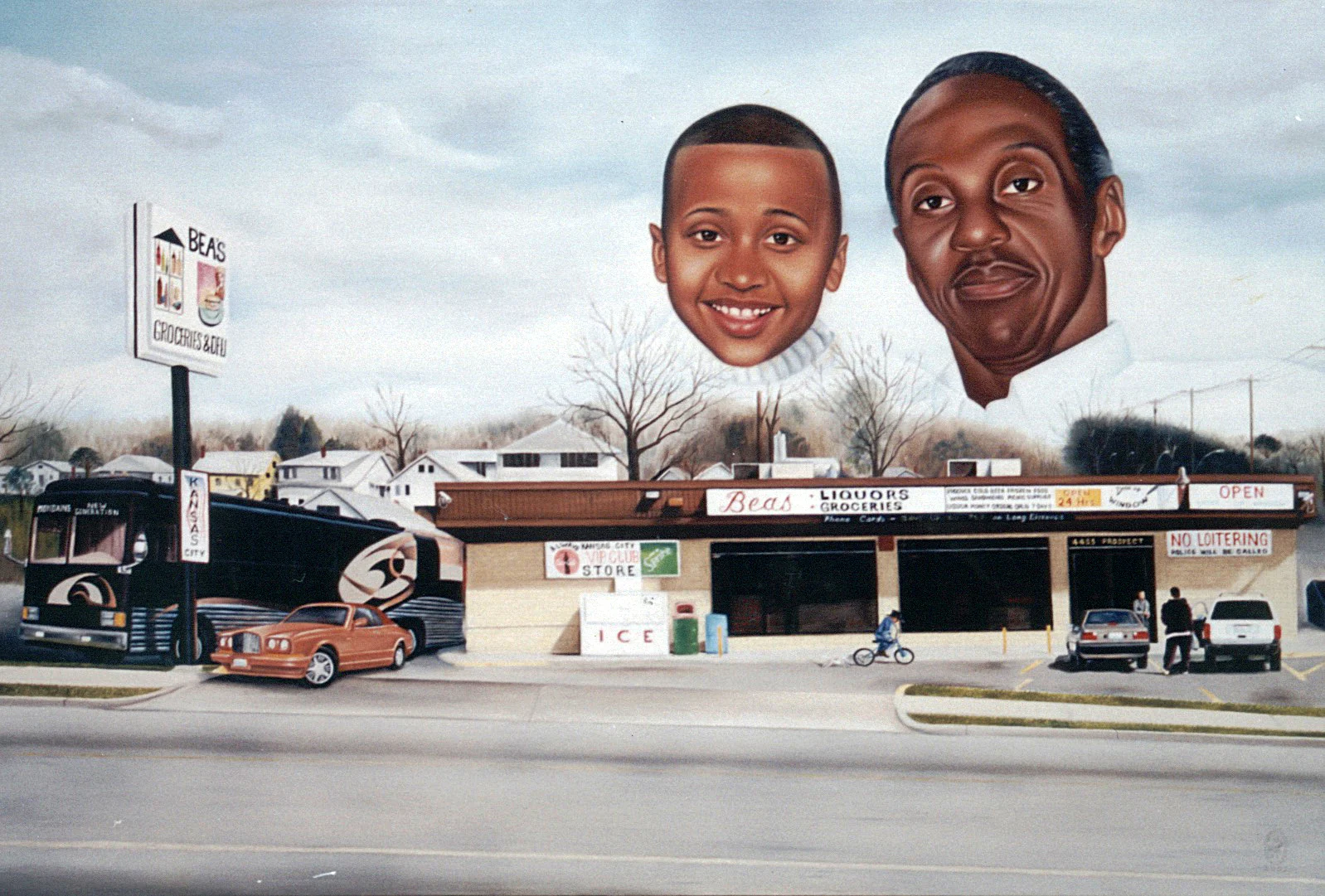

Another character in the film is Compton itself. For a city of less than 100,000 people, it plays an outsize role in the American imagination. It’s been home to an astonishing number of successful musicians, actors and athletes, but became, during the nationwide crime wave of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, a near byword for black violence.

In filming Wash in his hometown, Sean saw an opportunity to correct some of the misconceptions perpetuated by other depictions of the city. "Compton is often portrayed in film and television using certain stereotypes," he says. "We wanted to show a different dimension of the city through Wash's perspective."

In reality of course, the city is not a gangland war zone, but a suburb like many others, a world of “residential neighborhoods, and strip malls.” In this way, the film's setting perfectly compliments its subject: Wash, a man once deemed too dangerous to ever be allowed freedom, walks streets just as inaccurately portrayed as too dangerous to wander.

The emotional core of the short, a conversation between Wash and his adult daughters, proved just as challenging to film as it is to watch. He's long shared his emotions with his family through his art, embedding his paintings with his innermost thoughts and feelings in the hope that one day his children or grandchildren would decipher them. Words can come less easily – before filming, he’d never discussed with his daughters what it was like for them to grow up with their father in prison.

"We lived this life together, me inside and them outside. They’re supporting me, and I’m supporting them as best I could from where I was,” Wash says. "But that face-to-face patio conversation made me go back through time and remember all of the faces of all of the men in prison.”

In the scene, Wash cries quietly as his daughters describe the grinding normality of life with their father, brothers and uncles imprisoned. It was impossible for those behind the camera not to be affected. “It was extremely powerful,” Marisa remembers. “All of us had tears in our eyes.”

Looking back at his time in jail, Wash describes creativity as his “sanctuary.” As an art instructor, he passed the majority of his waking hours in the prison hobby shop, teaching classes and working on his own projects. He’s won his freedom, but he’s also starting over in his 60s, a convicted felon still answerable to a parole officer and fighting to clear his name.

His life combines the struggles of a freed man – looking for a lawyer, trying to challenge his record – with those of an artist, finding a time and place to paint and trying to earn a living from his work.

The politics of prison are behind him, but the politics of life as a professional artist are a new hurdle. “I’d love to meet other artists and find out what’s going on out here,” he says. “I’m learning a lot about art politics on a day-to-day basis. This is all new to me.”

You can buy original artworks by Mr Wash here and support Families Against Mandatory Minimums here.