China’s cosmetic surgery industry barely existed 20 years ago, but now it’s booming at an alarming rate. The number of operations carried out has more than doubled in the last few years, with more than half of the patients under the age of 30. Chinese photographer Yufan Lu has often been surrounded by friends who went and paid to change their faces. She used her camera to explore the thought process of those who have had or will have surgery, and to find out exactly what the surgeons will say to desperate patients.

Words by Alex Kahl.

As Yufan Lu graduated from high school in a north Chinese city of Tianjin in 2010, many of her classmates determinedly sought out cosmetic surgery as a way to change their image before they went to university. She says high school was an environment utterly focused on appearances, where people would be judged harshly on their facial features. “As a teenager I was easily affected by people’s judgements and popular media, which had little tolerance for anything other than beauty,” she says. Since this early exposure to these appearance obsessions, Yufan has kept a close eye on China’s cosmetic surgery industry, and in 2018 she decided to explore it in her photography.

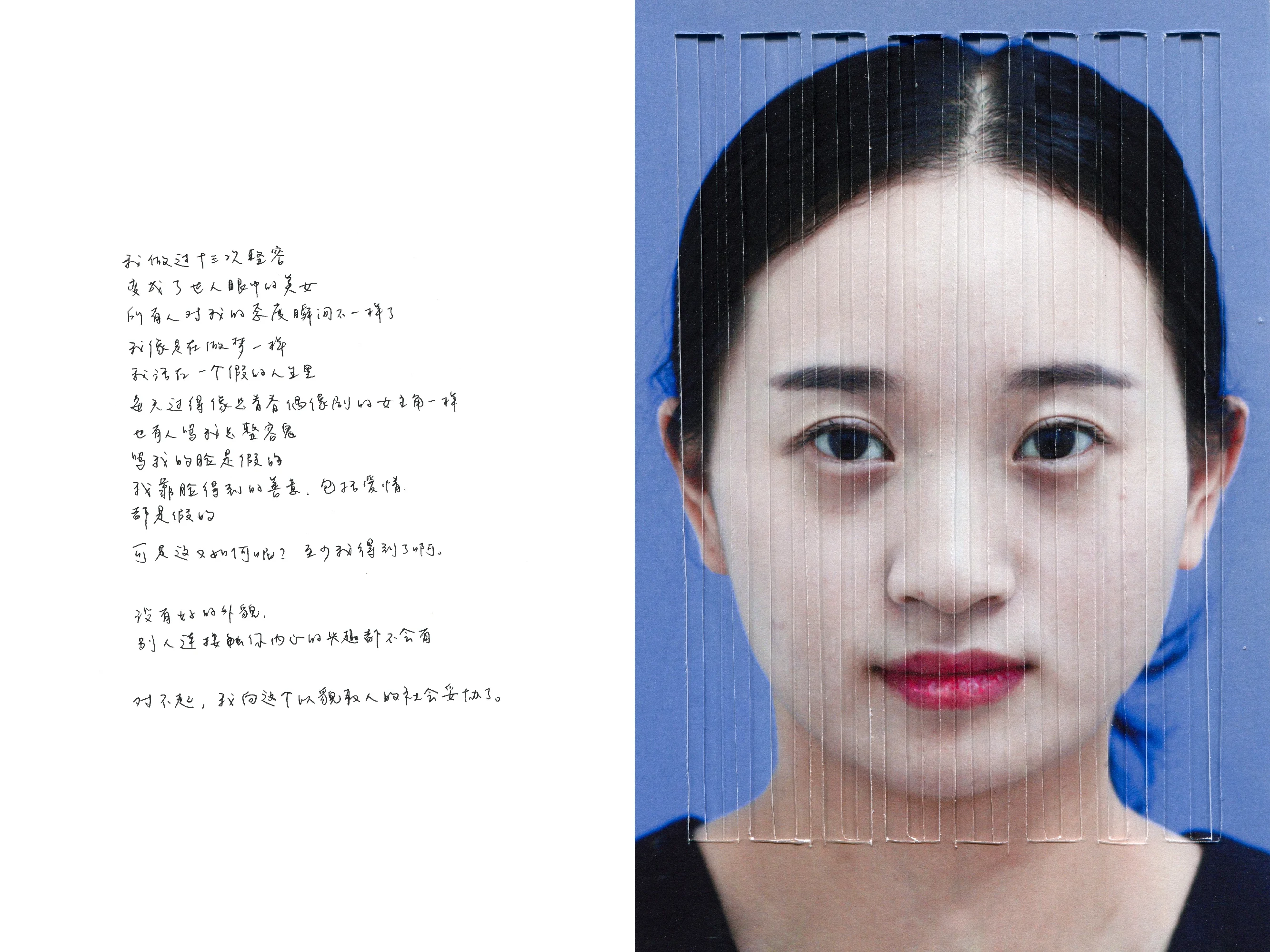

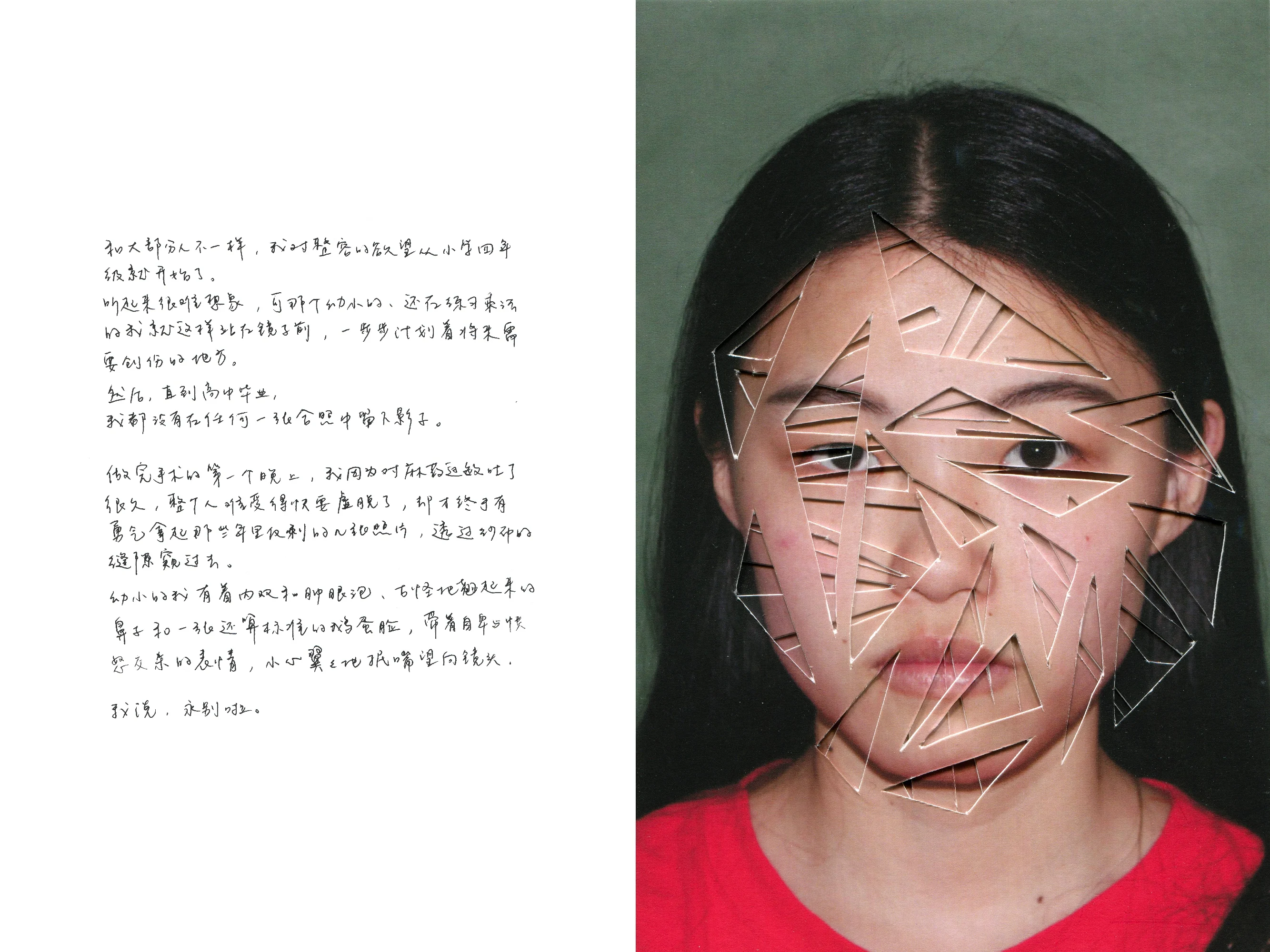

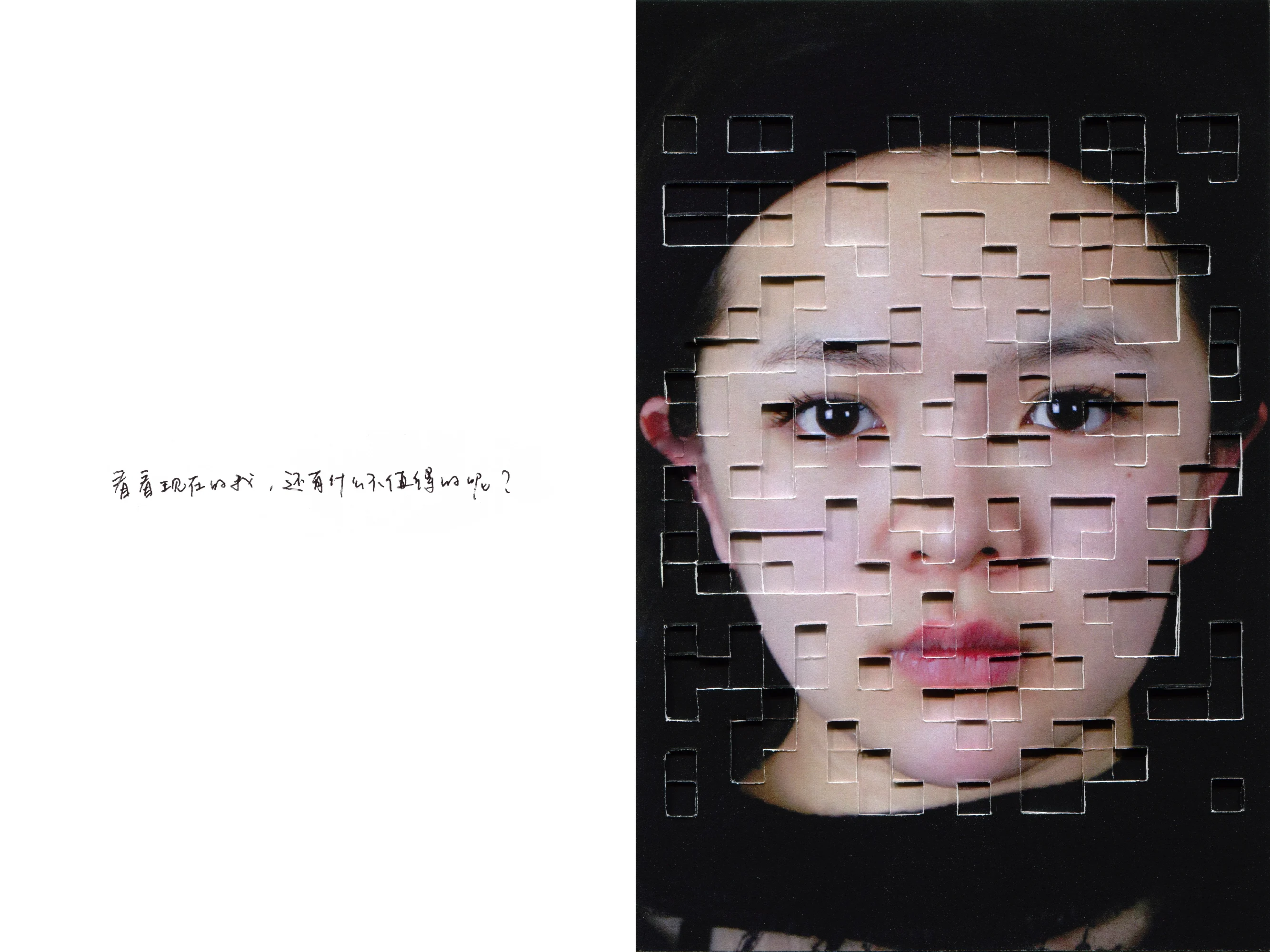

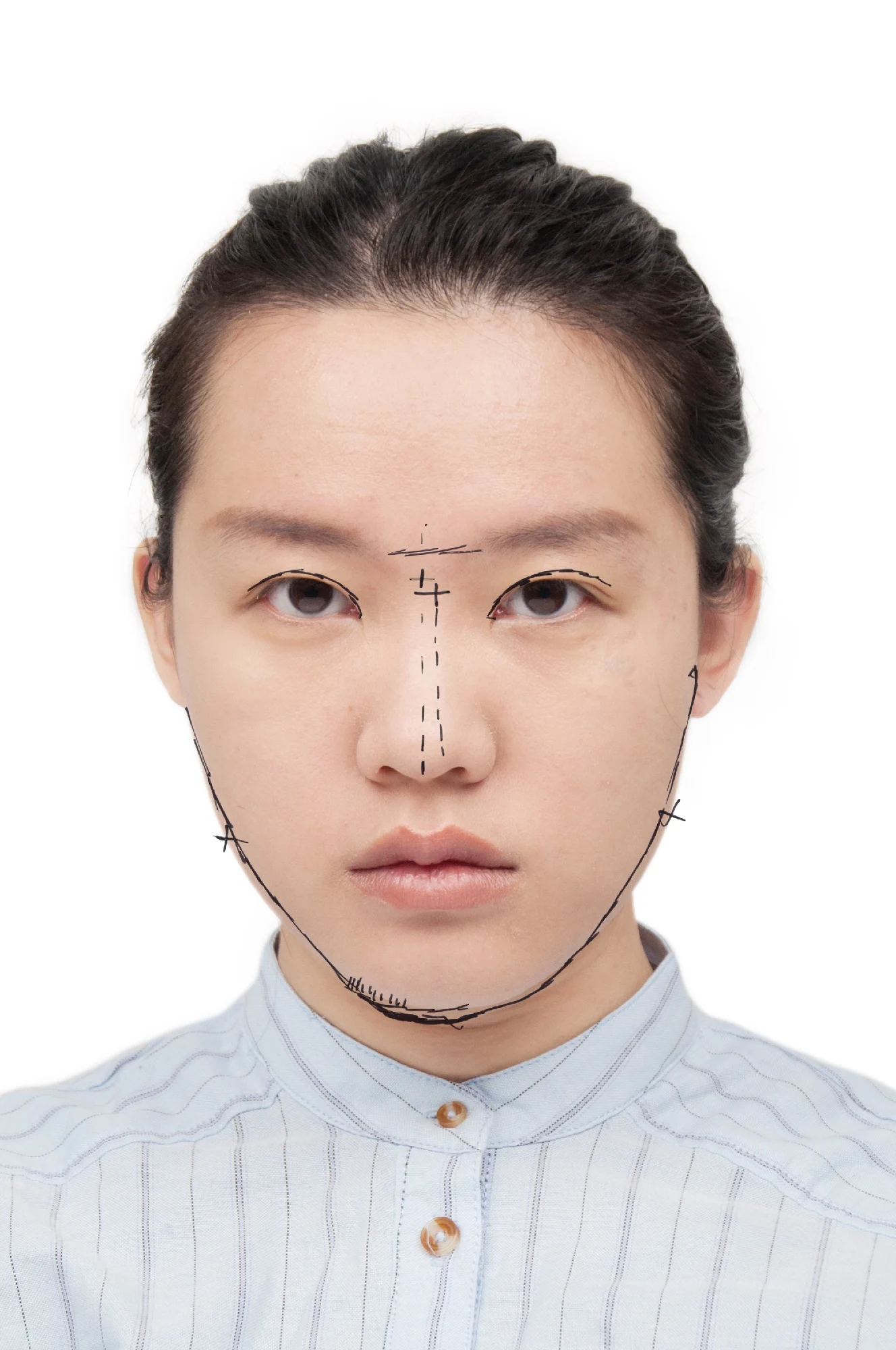

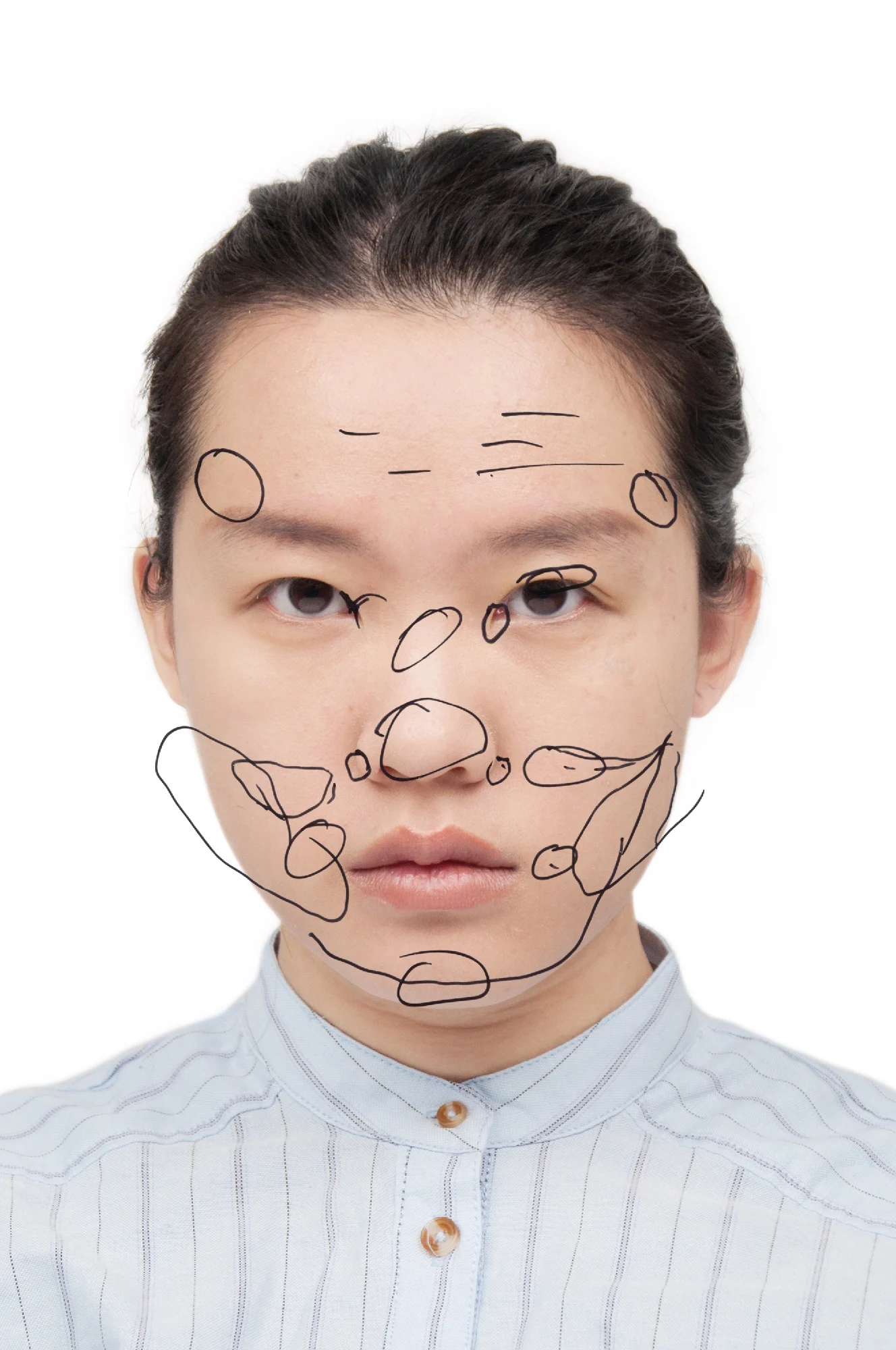

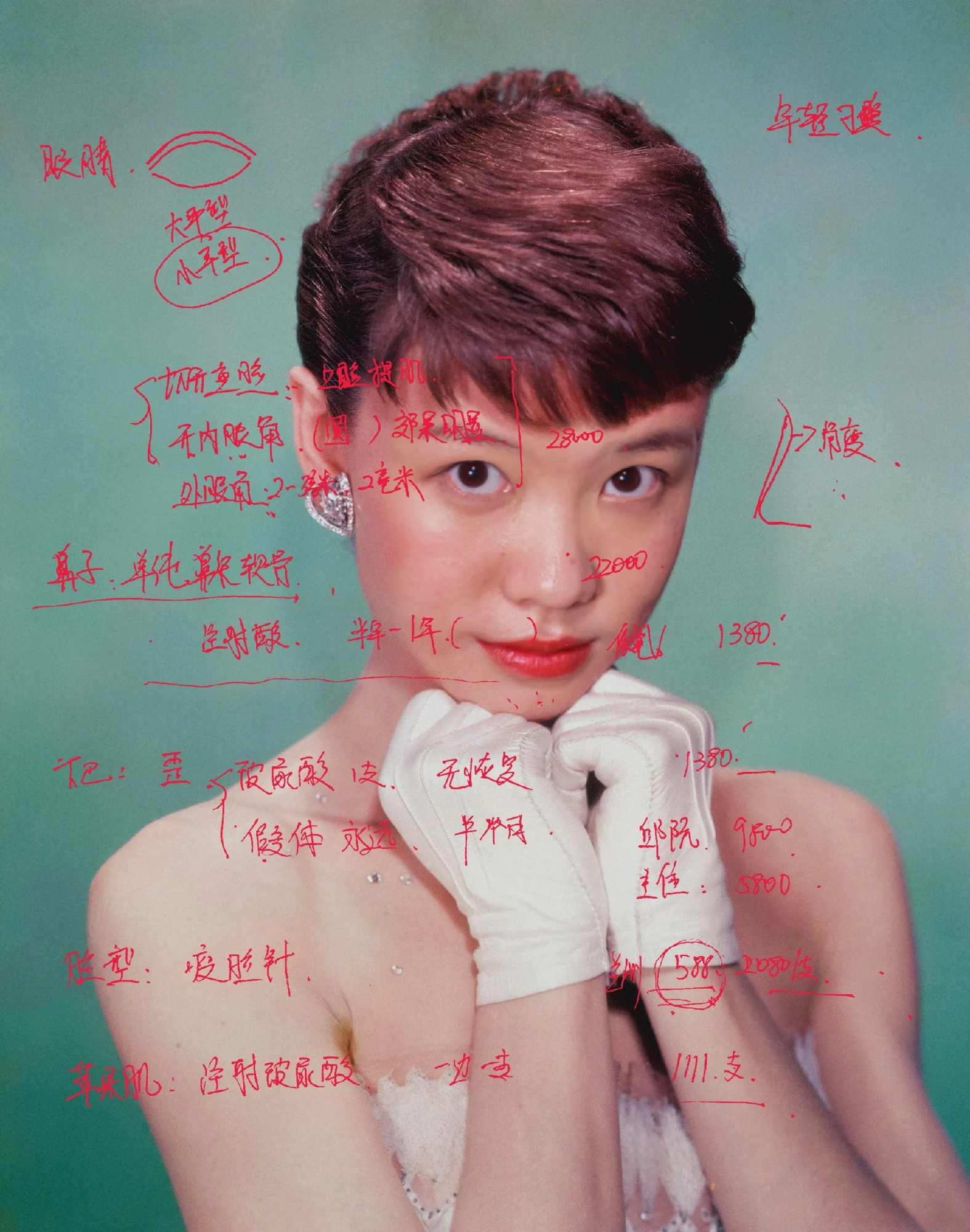

Make Me Beautiful, her ongoing project, is her attempt to understand a complex industry whose very existence and success highlights some controversial and concerning trends in modern society. Photos of her own face can be seen as well as pre-surgery portraits of women who took the plunge and paid for surgery, annotated with the thoughts and regrets of others who had done the same. “These images feel like post-mortem photos to me…looking at them I get such a sense of what was lost,” she says.

She began the project by taking a passport-style self-portrait of herself and sending it off to cosmetic surgeons to see what changes they might suggest for her. “That was before I studied anything about the industry,” she says. “I just had this impulse to know how my face looks in the eyes of cosmetic surgeons – powerful people in beauty standards – and experiment on myself to see how I would react to these diagnoses.” The annotated photos she received back from the surgeons are surreal to look at. Some surgeons suggested smaller, more subtle changes, drawing a single dotted line down Yufan’s nose. Others really let loose, covering her with circles drawing attention to every one of her features.

I think this project gradually developed into a form of therapy for me.

The surgeons used theories to back up the changes they recommended. One was physiognomy, the study of assessing a person’s character based on their facial features, and another was referred to as the “golden ratio,” an equation that states a person’s face must be approximately one and one-half times longer than it is wide to be considered “beautiful.” “To be honest, I think they made good points, especially when they quoted these ‘scientific’ theories to justify their diagnoses,” Yufan says. “After receiving more or less the same suggestions from different surgeons, I began to understand how difficult it is for someone who’s not confident in their appearance to resist cosmetic surgery.”

There were some surgeons, though, whose exaggerations and lies worried Yufan about the state of the industry. Some told her she could choose any type of face she liked, when in fact the appearance of the original face massively limits what’s possible in surgery. Others named the products that they would be injecting into her face without explicitly explaining what they were. Some of these products Yufan knew to be illegal in China.

These images feel like post-mortem photos to me… I get such a sense of what was lost.

At school, Yufan would only take pictures of her friends, but while studying Photography and Urban Cultures at Goldsmiths, an interdisciplinary program on photography and sociology, she learned to combine our visual expression with academic research. Using this training, she began research on China’s plastic surgery industry, and didn’t have to look far to find the statistics. The numbers presented vary, but a quick glance at some sites tells you that even at the lower end, they’re surprising. The cosmetic market in China is growing at a ridiculous rate, with annual increases in the number of surgeries performed regularly coming in at 20% or more. It rivals the US for the largest market for surgery on the globe.

Apps are being developed that can immediately analyze the user’s face and “grade” it based on its attractiveness, before making suggestions for changes and matching the user to a surgeon who can perform them. The process is becoming dangerously similar to browsing items on a shelf. “I think it’s becoming more similar now. The way the beauty consultants and surgeons offer me different styles of face to choose from vividly reminds me of shopping for clothes in a mall,” Yufan says. “What’s different is that surgeons have more power over me, I don’t feel as much pressure saying no to a salesperson.”

As someone who has often felt uncomfortable with her appearance, you might think Yufan would be hurt by the drawings of the surgeons who responded to her, but the project has actually had the opposite effect on her. “I didn’t grow up in an environment where people expressed positive feelings, so I had quite low self-esteem and couldn’t help but think negatively about things,” she says. “I think this project gradually developed into a form of therapy for me. It’s as if by doing this project I separated the part of me who is unconfident about my appearance from the rest of my personality. I turned that unconfident part of me into something visual, and then I could see it from a less personal, emotional perspective. It’s still inside me, but I feel that I found a more comfortable way to live with my low self-esteem.”

Make Me Beautiful has shown Yufan that the problem isn’t the people seeking cosmetic surgery, but the industry itself. “It’s not really about one’s appearance, but more about profits. There are also risks (some even fatal) that the industry tries to keep secret or ambiguous,” she says. “For some, surgery is their last resort. I think instead of judging those who get cosmetic work done, we should think about what has gone wrong in society that this has become many people’s desperate source of hope.”