When Jacolby Satterwhite was a young boy growing up in Brooklyn, his mother developed schizophrenia and began drawing things she had invented. Encouraged by her, Satterwhite too began drawing. Now, his work—often created in direct collaboration with, or inspired by, his mother—is exhibited in MoMa. His work has been selected by Solange Knowles as part of her guest curatorship for WePresent. Here, he tells art historian and writer Ferren Gipson his truly extraordinary story.

“I've always been fascinated by Jacolby Satterwhite’s ability to usher viewers through the numerous worlds of his mind’s galaxy. His digital narratives both affirm and encourage unique identities in the space of art and technology. He depicts the vibrancy of surrealism by centering authenticity and otherness. Whether it’s using dance as a forum or archival footage to evoke a spirit, his work sets a precedent for the kind of impact and influence culture has on creative expression, invention and autonomy.”

– Solange Knowles

Early foundations

One needs to think fast to keep pace with interdisciplinary artist Jacolby Satterwhite. His creativity is matched in vigor by his staggering work ethic, which is fortunate because his work is in increasingly high demand.

“This [year] is the busiest I’ve ever been in my life,” Satterwhite says from his home in Brooklyn, New York. He is currently preparing for several yet-to-be-announced projects within the coming year.

Throughout his practice, he creates fantastical, layered worlds that provide space to explore abstraction and concepts, including commercialism, absurdity, Blackness, queer identity, and his own lived experiences.

The origins of Satterwhite’s artistry and tenacity are evident early on during his childhood growing up in Columbia, South Carolina. Having grown up on a dead-end street surrounded by woods, he describes his childhood as solitary, but his family were involved with the church, which enabled him to take art classes at Bible school around age four. “I used to always draw these abstract drawings of Jesus, but in the cosmos,” he says.

When Satterwhite was around five years old, his father lost his local grocery store business, which led to financial troubles for his family. During this same period, his mother’s mental health started to decline. She began to make schematic drawings of inventions to sell, and Satterwhite was fascinated by her ingenuity. She encouraged him to learn to draw so that he could assist her, and he viewed his mother as having a similar poetic genius to Leonardo da Vinci.

There were toxic relationships, there was racism, there were all kinds of crazy things I went through—but I came out strong.

“Over time, her mental health [diagnosis] became schizophrenia, and I started to understand that she wasn’t an inventor,” says Satterwhite. “Because of her paranoid schizophrenia, I wasn’t able to go outside and do much, so I spent most of my time making paintings and drawings, and playing video games. It was very solitary. It was very isolated and digital.”

While his mother played a key part in cultivating his artistic interests, Satterwhite cites surviving cancer as a source of his ambitious nature. He was first diagnosed at 11 and had surgery on his right arm—his dominant arm—the following year. Cancer returned when he was 17, but he went into remission after several rounds of chemotherapy. “I felt like everything [was] heightened my entire life,” says Satterwhite. “Every day felt like a penultimate episode, and I wanted to make it matter and leave something behind.”

An emerging art practice

From age 15, Satterwhite attended the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities, and his path to transferring to the prestigious school could be ripped straight from the pages of a novel. He originally attended his local high school alongside kids he’d grown up with for years. He wasn’t enrolled in an art class, but when his best friend needed help to pass his art course, Satterwhite allowed his friend to pass off his personal drawings and paintings as his own. Here’s where things get wild.

The art teacher, Janice Johnson, was so impressed by the artworks that she entered them into a competition, where they won first place. The two boys forgot that Satterwhite had signed the backs of each work, and their scheme was discovered after they were taken down from the competition show. Seeing his artistic promise, Johnson gave Satterwhite the option to apply to the arts boarding school, where he could further realize his creative potential. She worked with him every day after school until eight o’clock to help him prepare his portfolio and he was one of 10 students to be accepted into the visual arts program that year.

I used to always draw these abstract drawings of Jesus, but in the cosmos.

“I started to prove myself through my painting skills,” says Satterwhite. “I really was ambitious about it, and I did 20 giant paintings in my senior year and it ended gloriously. It was a hard time. There were toxic relationships, there was racism, there were all kinds of crazy things I went through—but I came out strong.”

Reconnecting with his mother

Thanks to his rigorous high school studies, Satterwhite was confident and capable as he entered undergraduate studies in painting at Maryland Institute College of Art. When the time came to think about his senior thesis project, a professor encouraged him to do more work to find a conceptual grounding for his practice, suggesting that he return home to find something important and influential to him.

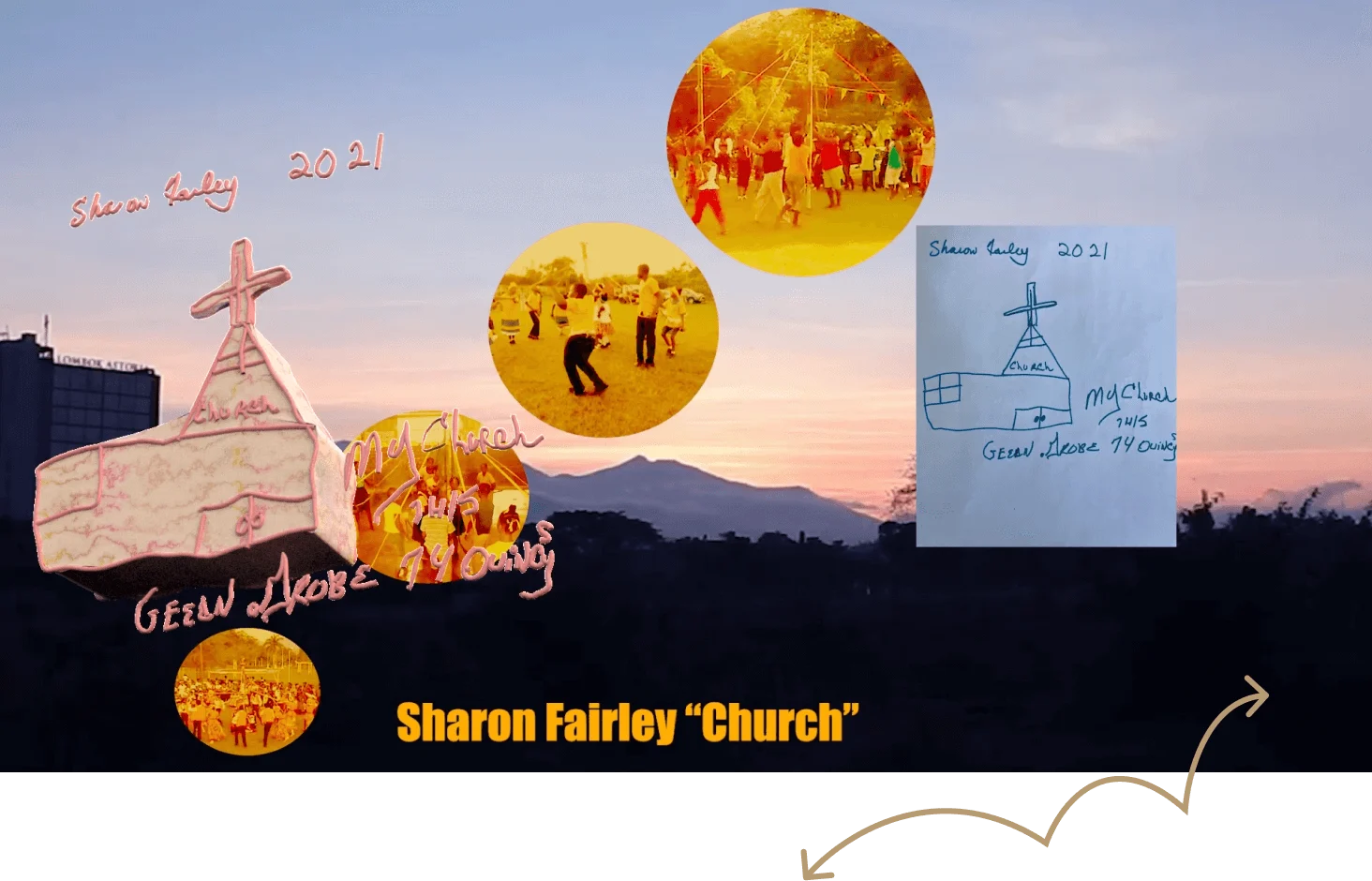

“I brought my mother’s drawings and he said, ‘This is going to be something you’re dealing with for the rest of your life,’” says Satterwhite. “I made [them] into this conceptual art project where [they were] juxtaposed with family photographs, which eventually became this piece called ‘The Matriarch’s Rhapsody.’”

Once he started to examine his mother’s work through an artistic lens, he began to see similarities with the performance scores created by avant-garde artists of the Fluxus art movement in the 1960s.

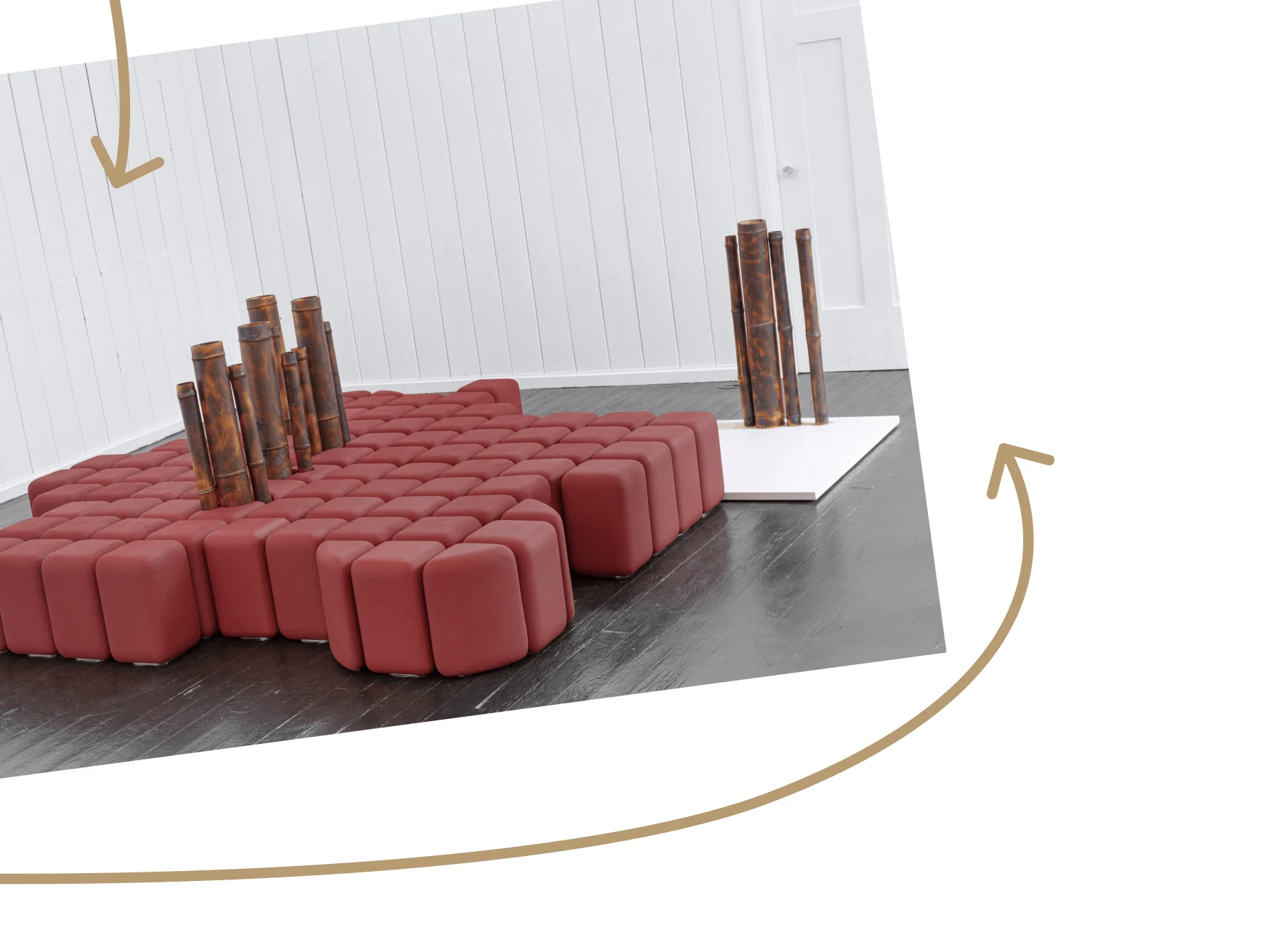

“My first attempt at trying to collaborate with her and find myself through her practice was actually making the objects in her drawings, performing the text, allowing the text to guide how to perform with those objects and creating a world building lexicon around this body of work that I inherited from her,” says Satterwhite. “It was sort of like a ritual. It was like carrying on an heirloom familial ritual to find myself.”

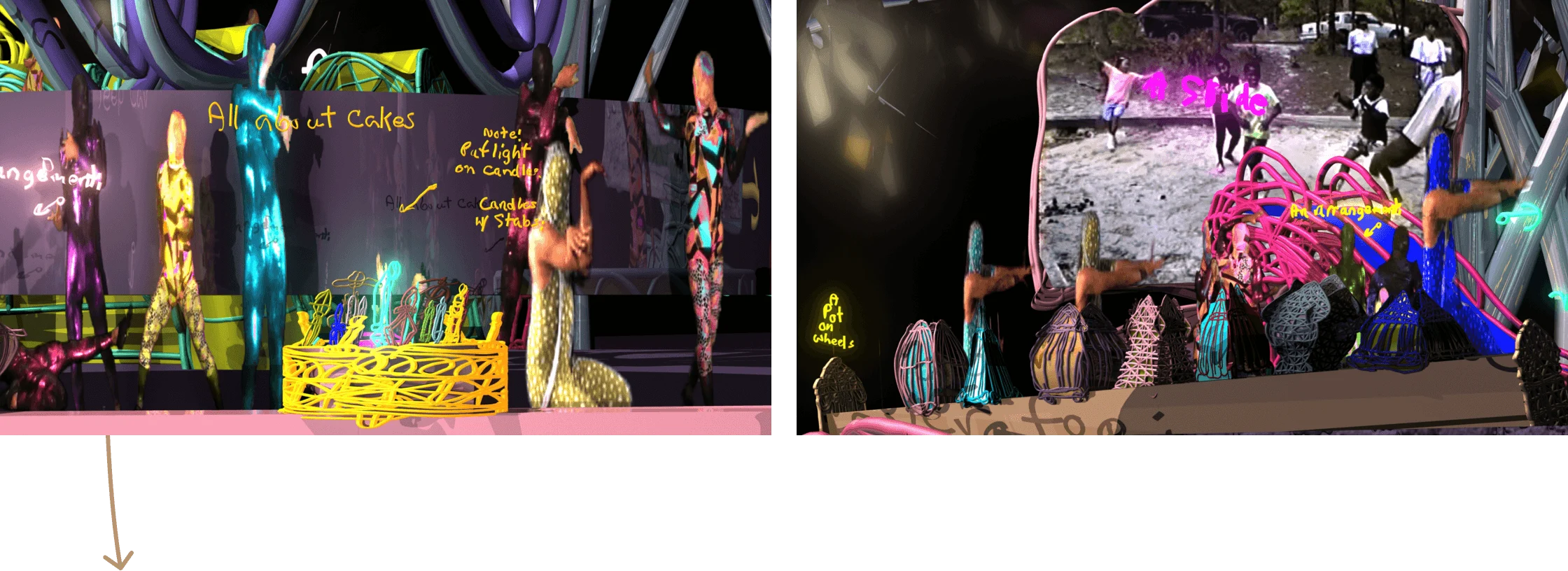

The final version of “The Matriarch’s Rhapsody” (2012) is now part of the Studio Museum Harlem collection and is a digital video work that includes animated performance and images from his mother’s original sketches, such as ideas for a dandruff brush and a cake slicer. The seedlings of this work, which began during his final undergraduate year, mark the first of several occasions where Satterwhite would “collaborate” with his mother.

Creating worlds in digital space

Satterwhite went straight to graduate school from his undergrad, earning an MFA in painting at the University of Pennsylvania in 2010. During his graduate studies, he participated in an intensive residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. It was at this time that he pushed himself to experiment with performance and explore themes of absurdity, even though he felt like he “didn’t know what [he] was doing” at first. From a technical standpoint, he also began to teach himself 2D animation.

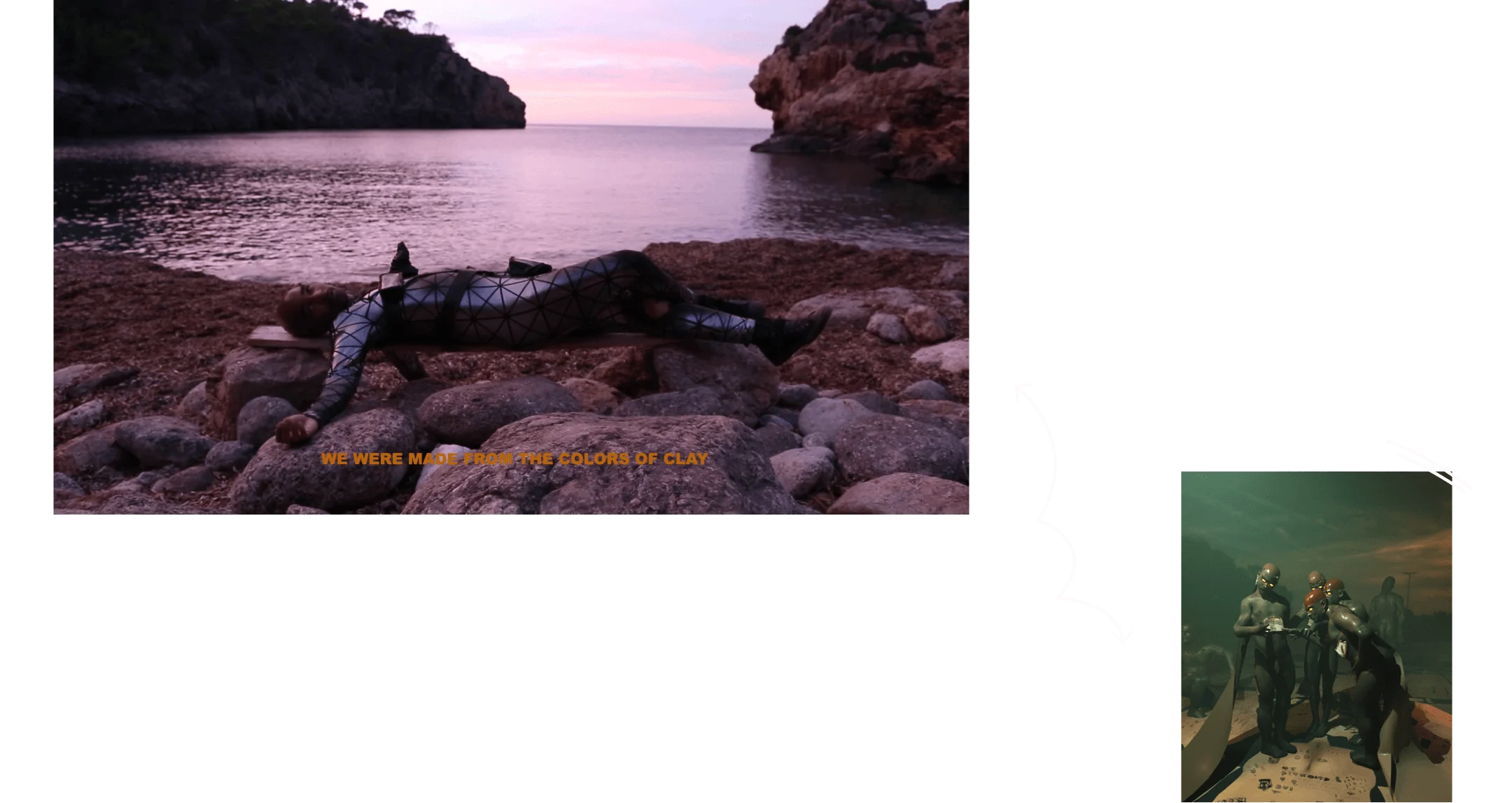

By the end of his graduate program, he created an early version of his video work “Country Ball 1989,” which he later reworked and retitled to “Country Ball 1989–2012.” Now part of the MoMA collection, the video includes a mixture of 3D animations, home videos of a family cookout, recreations of his mother’s drawings, and footage of himself voguing, which he describes as a way of drawing in space. The imagery comes together to create a fantastical world that’s rooted as much in his personal experiences as it is in art history.

I just want to be able to expand my studio, and then be a leader.

“I figured out that I could trace my mother’s drawings inside of 3D animation architectural rendering software with a stylist pen,” says Satterwhite. Tracing enabled him to remain faithful to his mother’s drawings and create a body of digital assets that he says reminds him of imagery from an Hieronymus Bosch painting or even the “Final Fantasy” video game. “I could composite [those assets] in a 3D animated space and make painterly landscapes that are four-dimensional or could be potentially VR [or] a video game. And that was my major ‘aha!’ moment.”

Merging soundscapes and landscapes

Satterwhite has a fearless approach to his practice, where seemingly no medium is off limits. In 2015, he worked with friend and musician Nick Weiss—one half of the duo Teengirl Fantasy—to create the trip hop electronica album “Love Will Find a Way Home.” The band is named Pat, after his mother Patricia, and is another form of collaboration with her, this time incorporating acapella recordings of songs and jingles she created.

“I wanted to make a virtual reality album,” Satterwhite explains. “The idea was to make a score where her songs, and her lyrics, and everything I made around the sonic atmosphere would influence a very conceptual visual album.”

It was like carrying on an heirloom familial ritual to find myself.

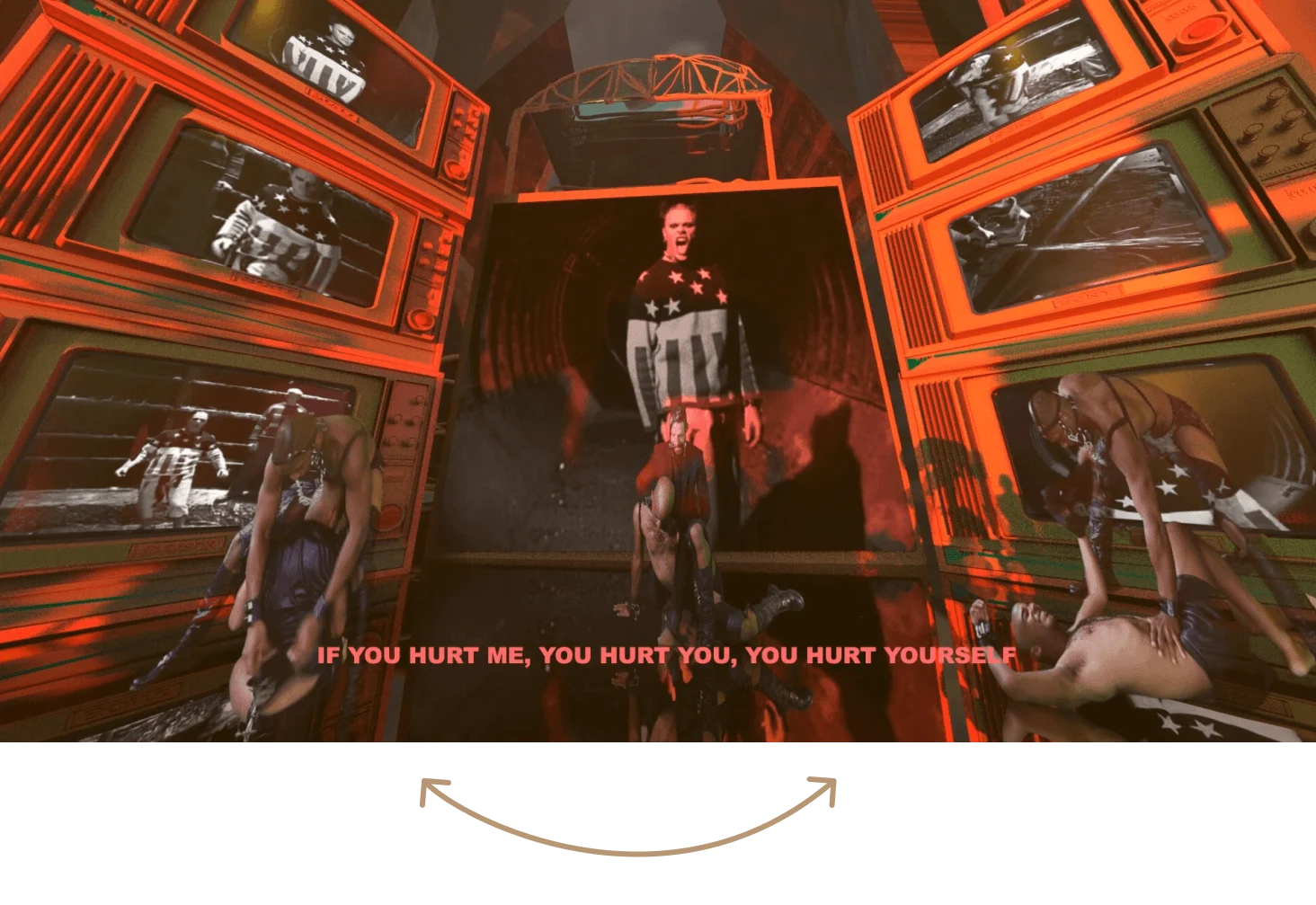

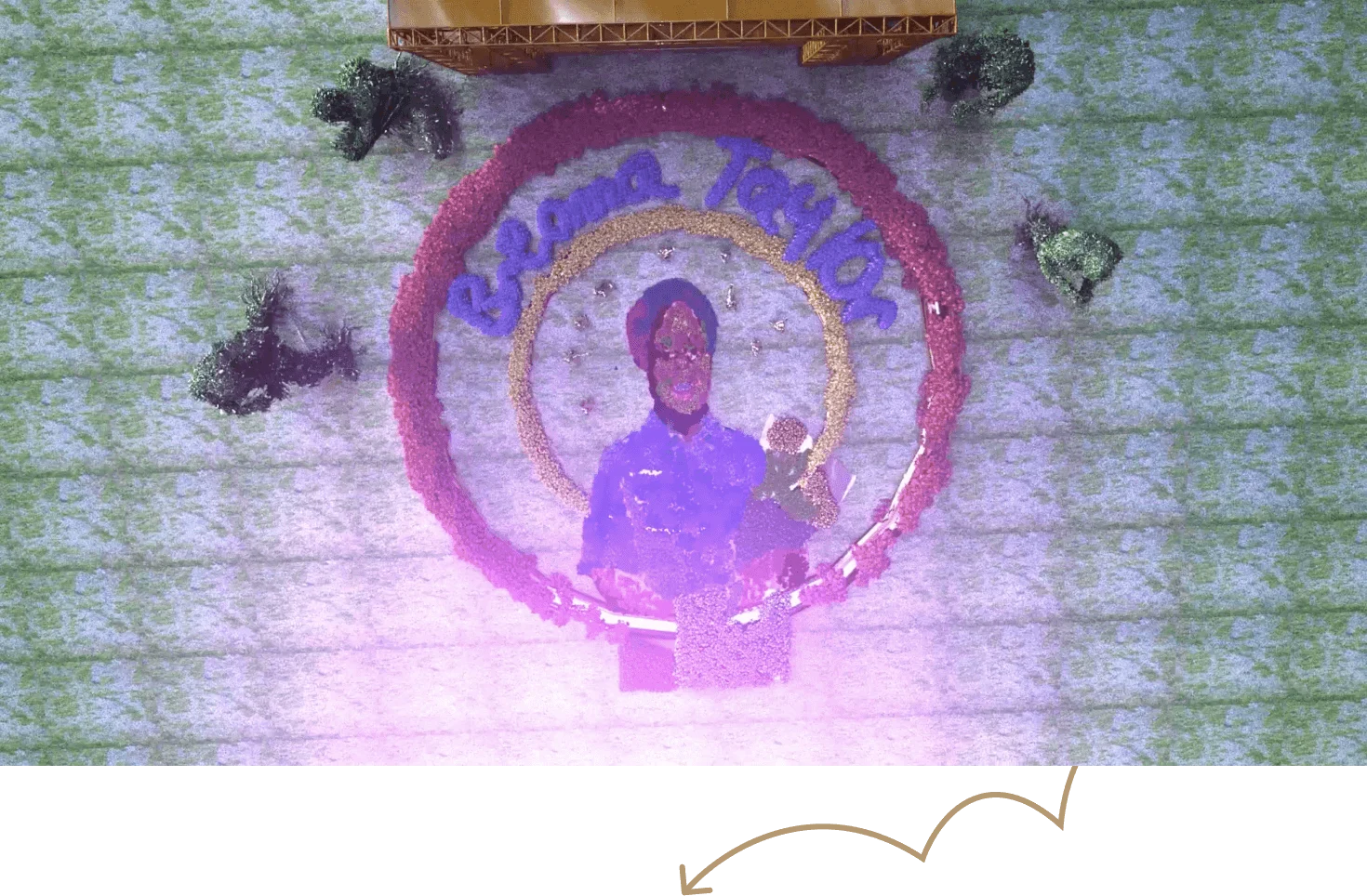

The accompanying visuals for the album include six 3D animated films collectively titled “Birds of Paradise” and three virtual reality films. The chapters of “Birds of Paradise” can also stand alone as individual works. For one chapter, “We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other” (2020), Satterwhite creates a utopian world where Black women have “peak agency,” and he depicts them as fembot-like figures fighting off adversity. The work was created during the period of protests surrounding the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

“I wanted to make it really repetitive like a video art piece from the 1960s, where you get exhausted watching her triumph and everything else is kind of being sublimated,” says Satterwhite. “In the background, you see videos that reference zeitgeisty issues. But at the end she evolves into this bigger, more intense force, and the Breonna Taylor shrine pans out at the end.”

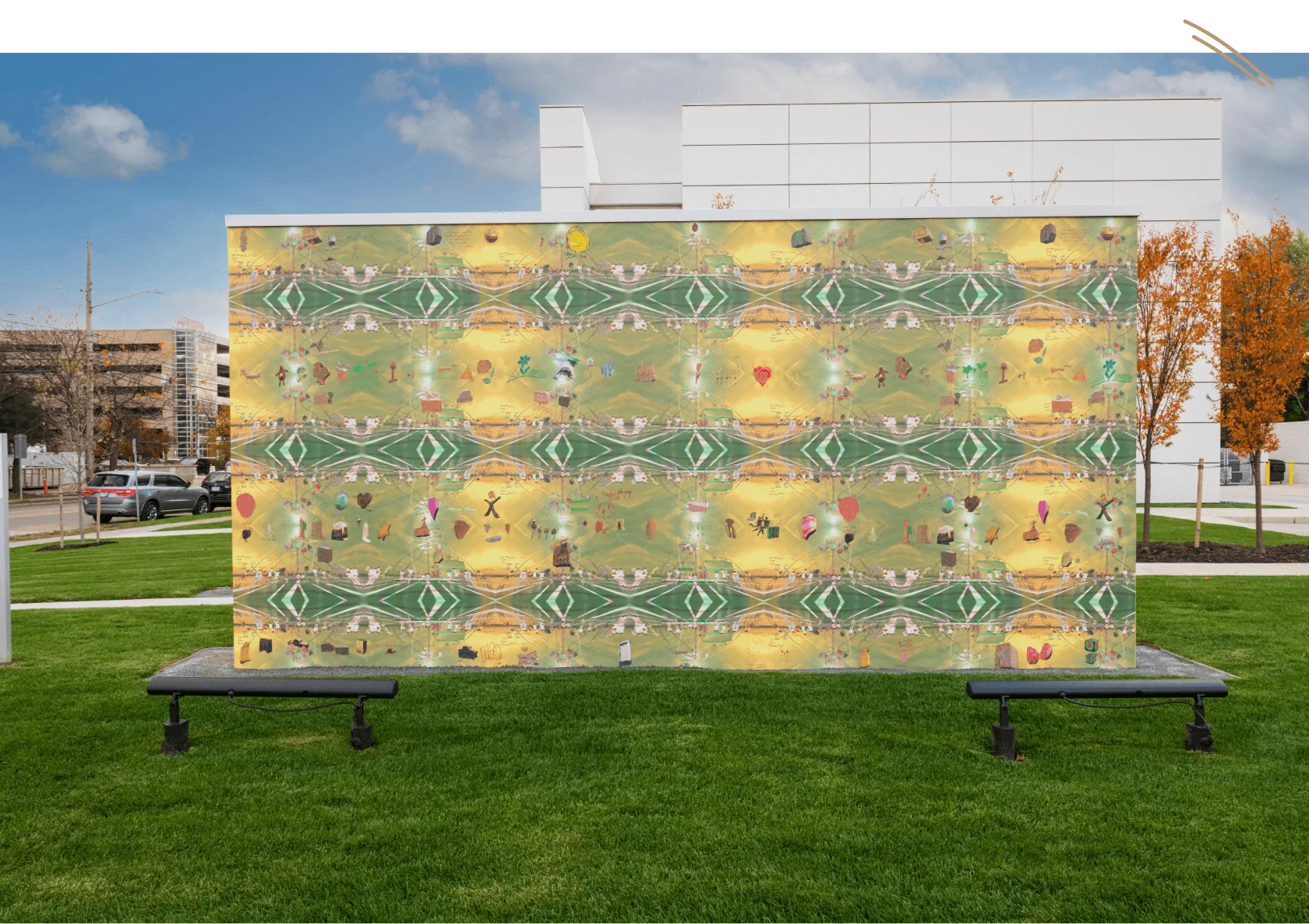

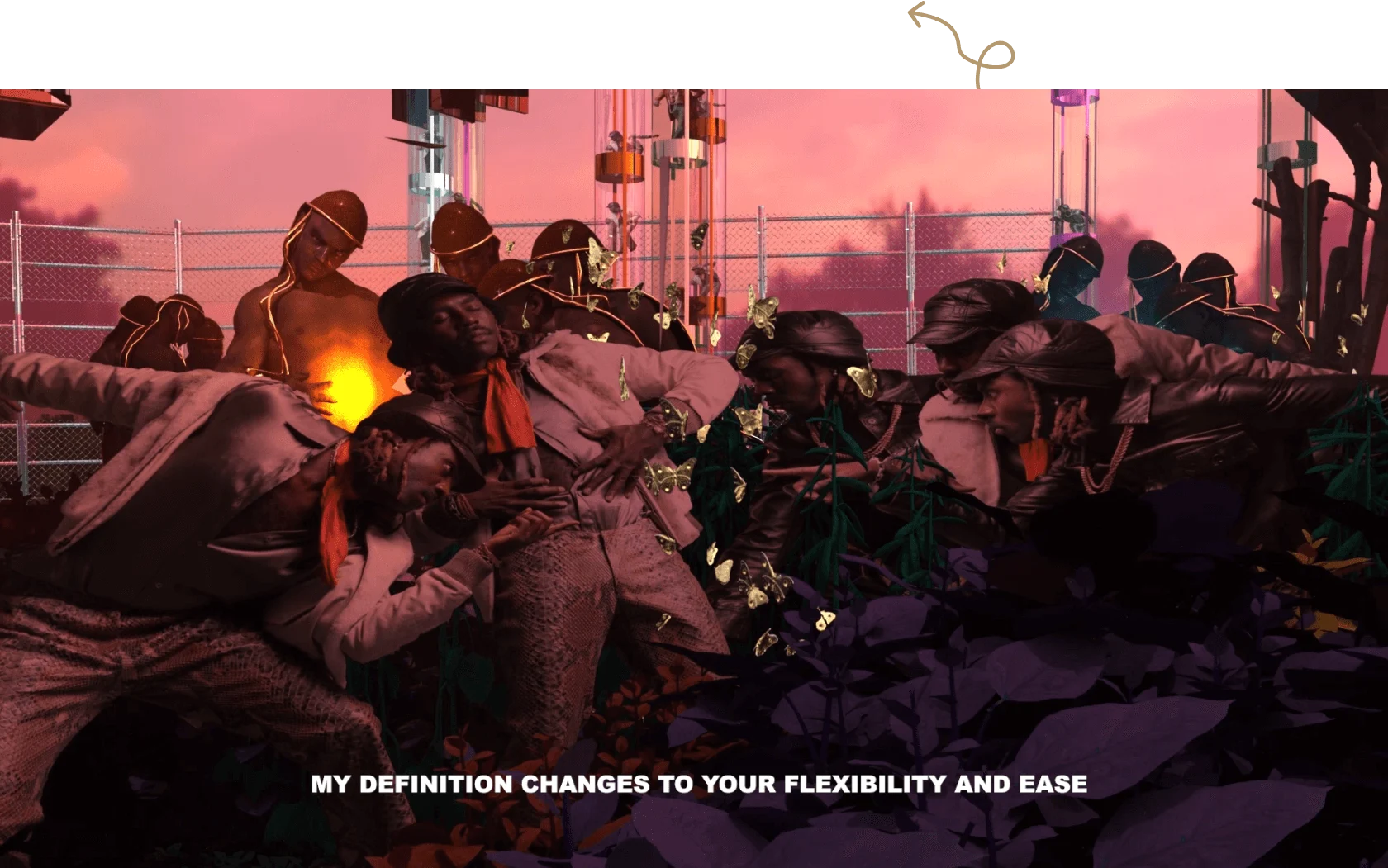

This practice of creating worlds is a recurring theme in Satterwhite’s work, and in a recent commission for the Cleveland Front Triennial titled “Dawn,” he worked with residents of the Fairfax neighborhood in Cleveland to make a public artwork for the Cleveland Clinic. Just as he collaborated with his mother’s drawings, he commissioned 100 people to create quick sketches representing their ideas of utopia, which he then brought to life digitally.

“I collected the drawings and built them, and I made this public artwork monument… it was like this long wall with a video embedded in it,” Satterwhite says. “I rendered the architectural space of what their utopia was, and I made a wallpaper with all their objects, and you could see their names connected to the objects. And now I'm working on the video game part, and the CGI film.”

Satterwhite works ceaselessly—sometimes literally working in his studio around the clock—and things don’t appear as if they’ll slow down soon. Even with five biennials and triennials, multiple exhibitions in some of the world’s most prestigious art institutions, and a collaboration with Solange Knowles for her “When I Get Home” visual album under his belt, he still has the headspace to think about the future and the drive to push his work further.

“I’m currently making oil paintings, and I’m working on a video game, and I’m working on public artworks, and CGI experimental animations and sculptures,” says Satterwhite. “I want to become better, I just want to be able to expand my studio, and then be a leader.”