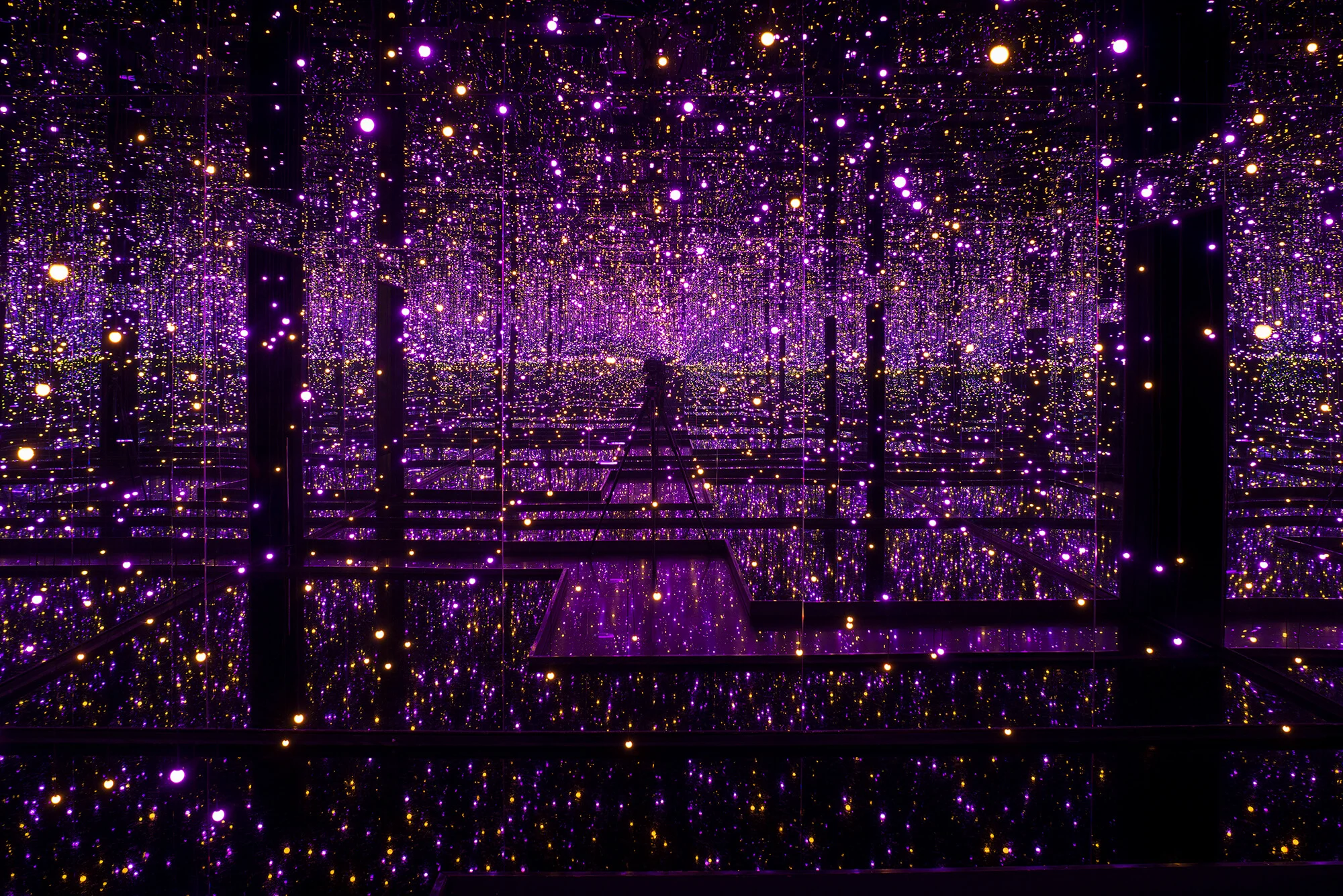

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is a phenomenon. Through her talent, determination and vision she’s spent eight decades taking on the white, male art establishment – and winning. In recent years her work has found a huge new audience in her international exhibitions and on social media, from her celestial Infinity Mirrored Room installations to her expansive paintings.

But there’s much more to her than that. And though she’s reinvented herself and her art on several occasions, as curator Katy Wan explains, one of her main goals has always been to inspire joy and happiness.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.

She embraced art in a difficult childhood

Kusama was born in Matsumoto, a mountain-city in central Japan, in 1929. Her upbringing was not always a happy one as her parents did not support her making art.

Aged ten Kusama had her first hallucination, when she saw the violets in the family field speaking to her. These experiences continued and searching for a way to process her terror, Kusama threw herself into drawing.

Although her mother discouraged this passion, Kusama went on to art school in Kyoto where she trained in nihonga, a form of classical Japanese ink painting that combined both Japanese and European influences, although she would later move away from nihonga itself.

She wrote letters to Georgia O’Keeffe

Kusama is really struck by O’Keeffe’s prestige as an artist, despite being a woman in an art world that is still dominated by men.

She revolutionized New York’s male-dominated art scene

New York in the late 1950s was not a welcoming place for a young, female Japanese artist. Kusama arrived in 1958 and set about developing her practice and building her profile with the mixture of ambition and determination that drew her from Japan in the first place.

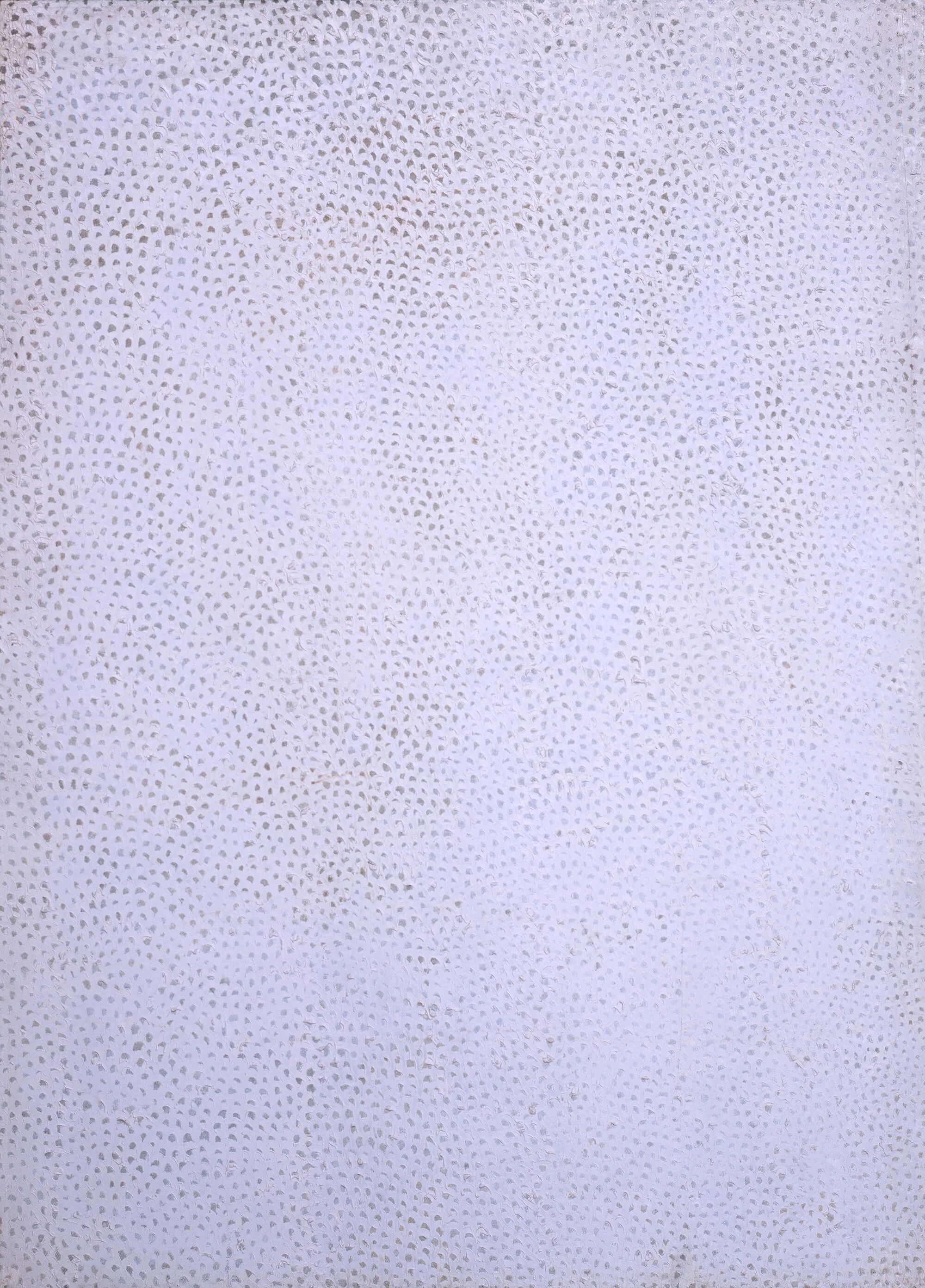

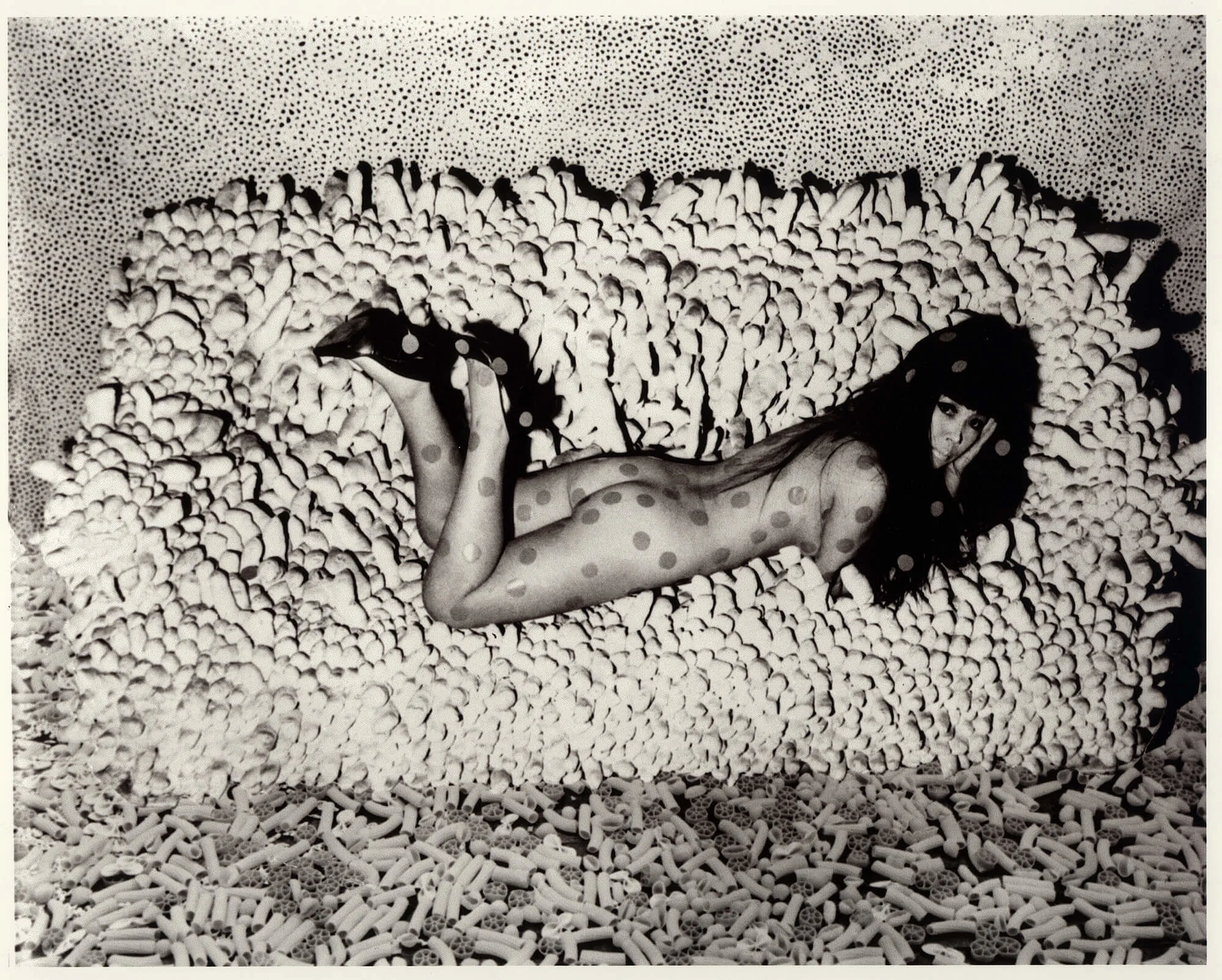

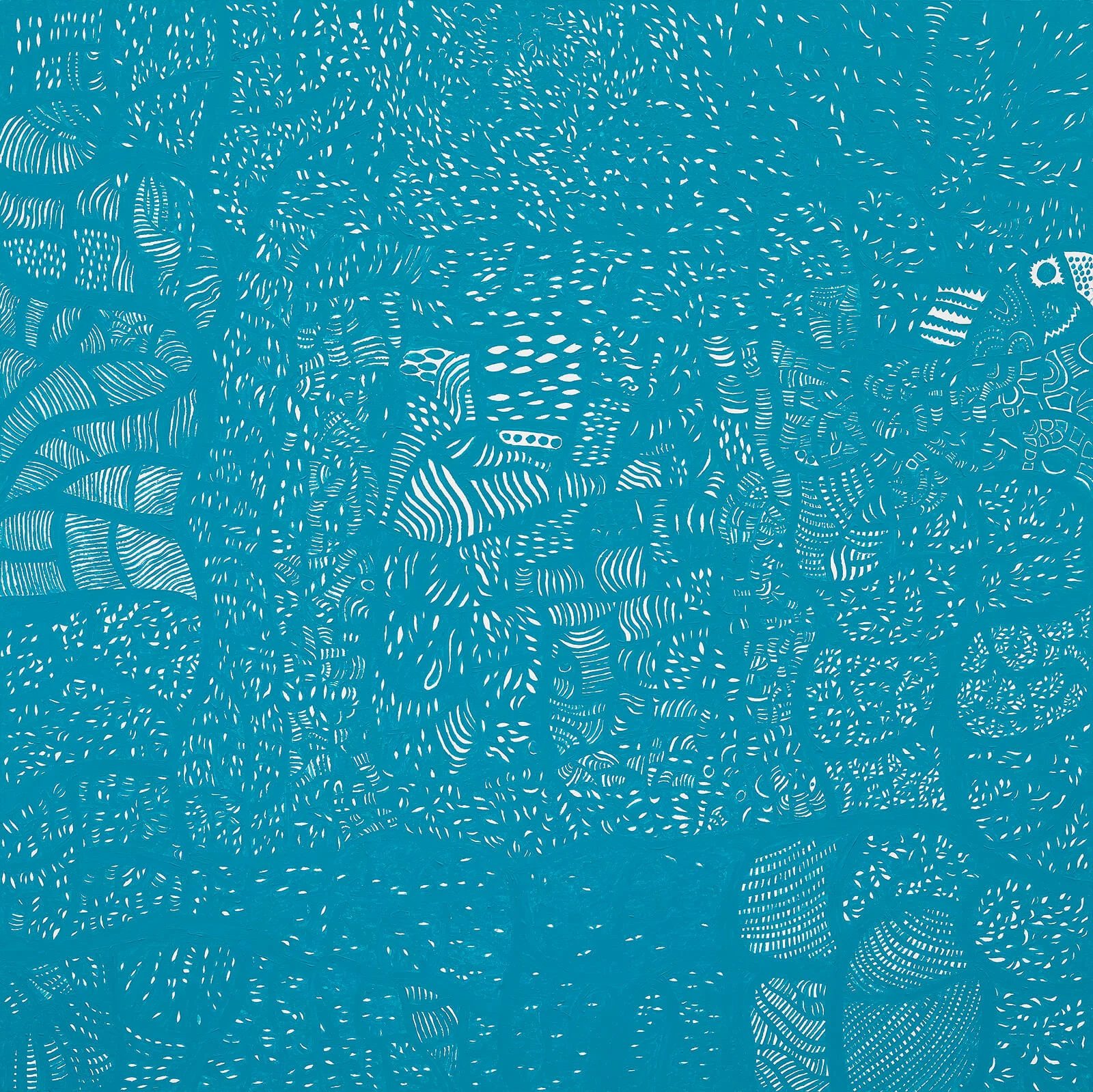

She made huge black and white paintings made up of tiny arcs, which she called “infinity nets." She’s continued to make them throughout her life, as well as “accumulation” sculptures (objects like couches and chairs covered with soft, phallic shapes), and staged happenings and performances.

Sometimes that meant covering her own body – or other painting people’s bodies – with dots. Other times it meant something completely different, as in Walking Piece, where she paced the streets of New York wearing a floral kimono and carrying a parasol, a fearless celebration of her own cultural heritage in a Western landscape.

Kusama was unstoppable. In the late 1960s she established Kusama Enterprises, her own line of dresses and textiles. This was an exercise in self-branding, based around the dots for which she was already well-known. Kusama saw that through fashion, she could reach far more people.

“Self-representation is an important aspect of Kusama's practice,” Katy says. “She is immortalising her own image by harnessing the power and potential of fashion. Not only in terms of making herself recognizable, but in realising that having other people walk around in your designs is one of the best forms of advertising.”

She has become an Instagram sensation

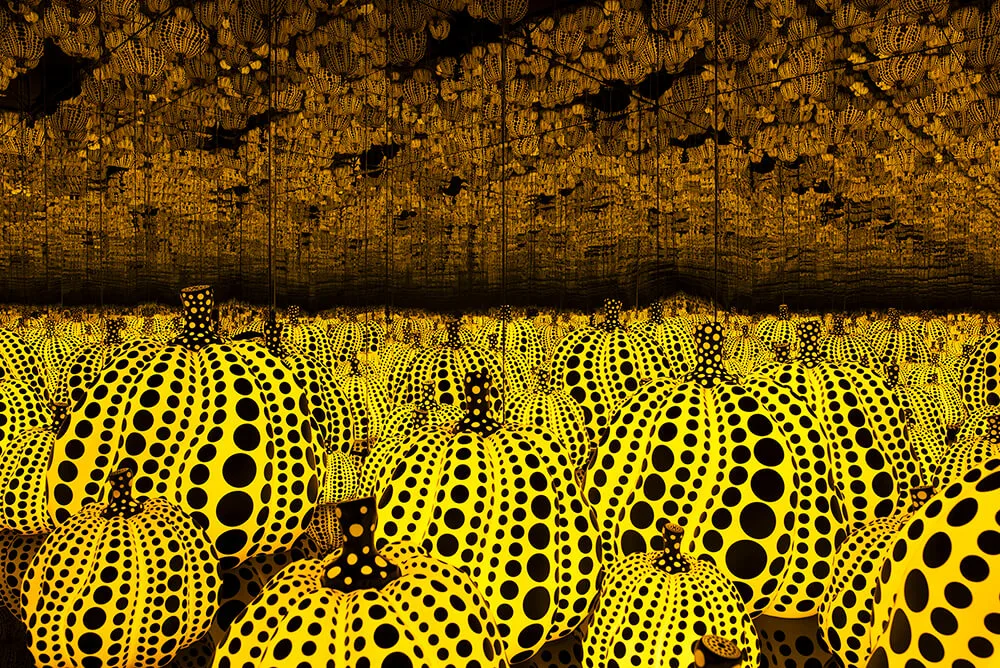

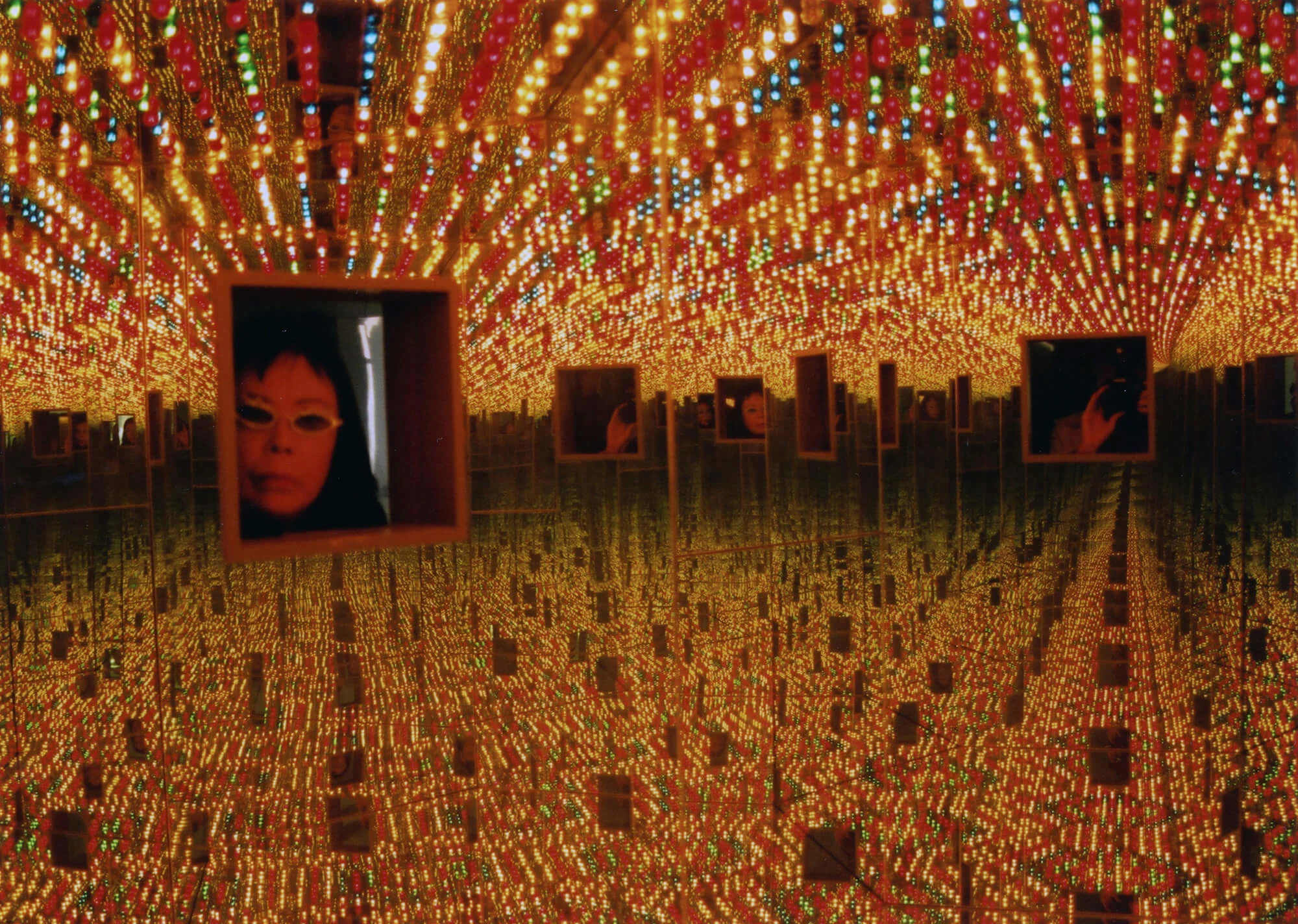

The objects within it multiply forever.

She knows how much we love to look at ourselves

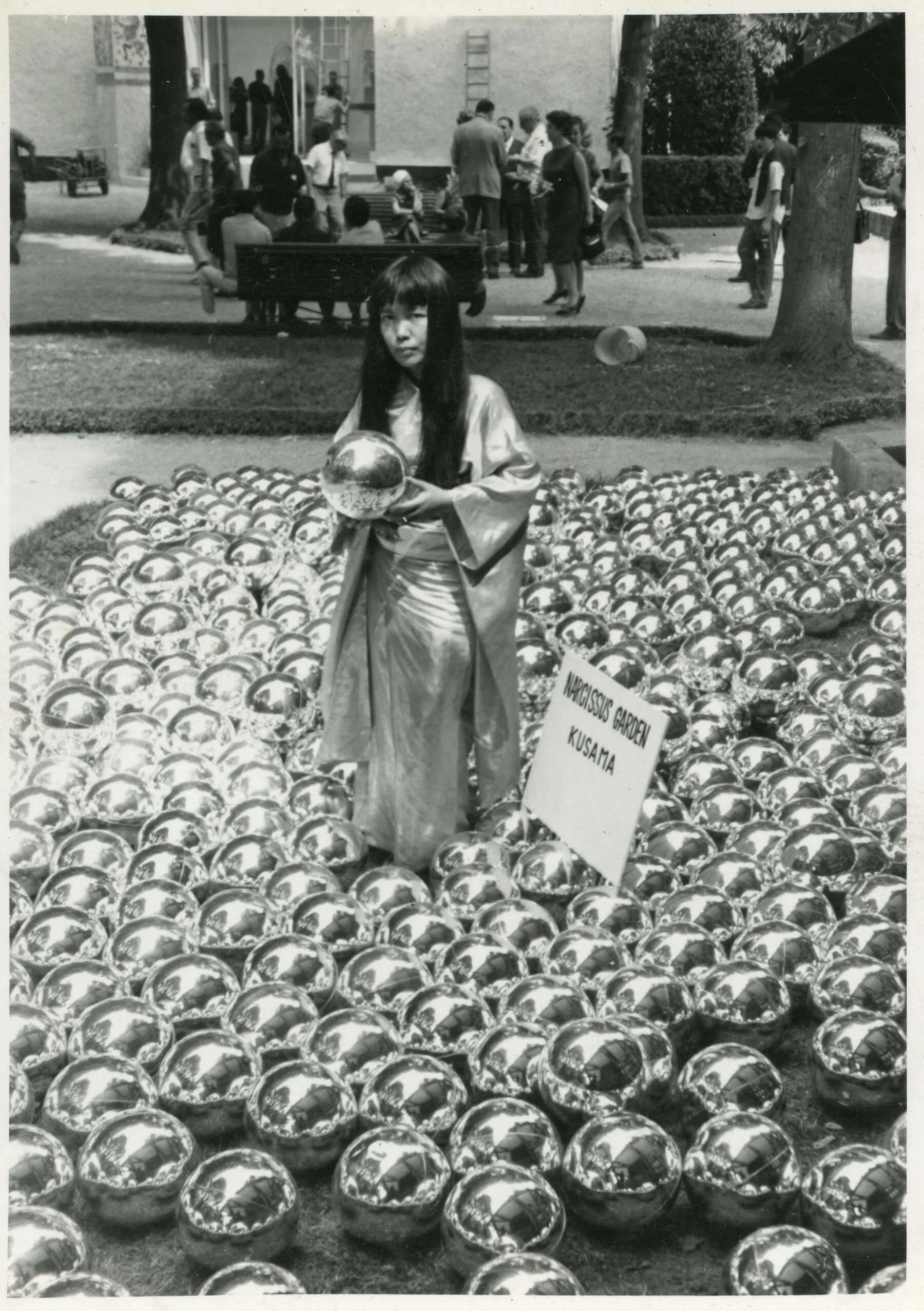

Kusama’s self-belief crops up throughout her practice. When things don’t turn out the way she wants, she makes them happen. In 1966 she wasn’t officially invited to participate in the 33rd Venice Biennale (an international exhibition which takes place every two years), so she staged an unofficial performance, installing a sea of silver globes on the lawn in front of the Italian Pavilion.

For the piece, which she called Narcissus Garden, the artist stood among the spheres wearing a gold kimono with a sign that read “Your Narcissism for Sale.” Viewers could buy the globes for 1,200 lire (about $2) each.

Different versions of the piece continue to be shown today. The many thousands of selfies posted from inside her mirrored installations – #yayoikusama has more than 792,00 posts on Instagram at the time of writing – serve a similar purpose, offering a lens into our own egotism.

She manages her mental health through making art

She relies on her intuition

Throughout her career, Kusama’s work has been intuitive. She creates work based on her own psychological experiences and uses her art to come to terms with her compulsions and her visions.

"It’s been said that she doesn’t have to draft out her paintings before committing them to canvas,” Katy explains. “She is portraying exactly what she sees in her field of vision."

Color plays an important role here. Her vibrant use of color counterbalances her often serious subject matter. Take for example her ongoing My Eternal Soul series – bold, bright and often surreal paintings of faces and other sometimes threatening abstract forms, which demonstrate an intuitive approach to figurative art-making.

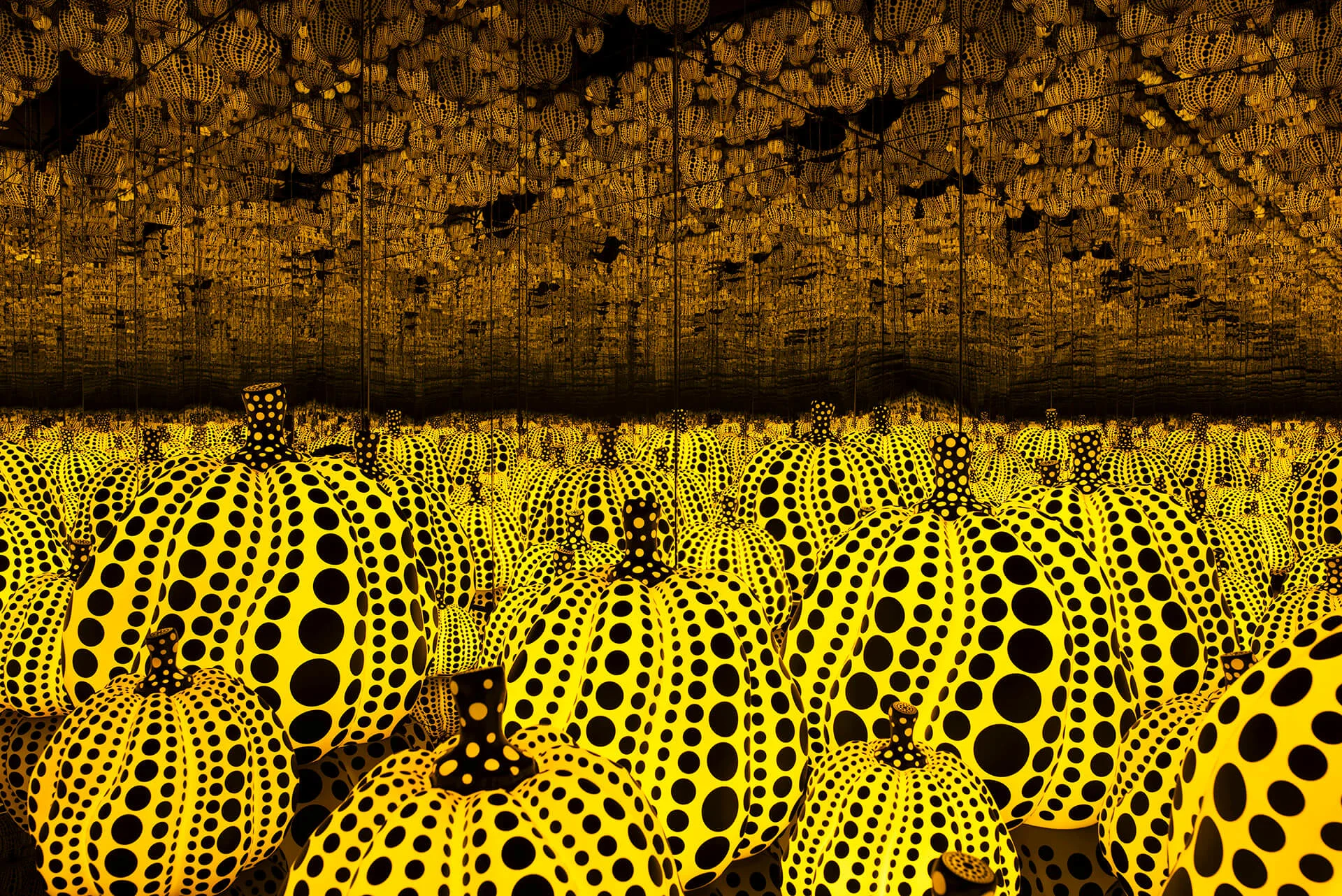

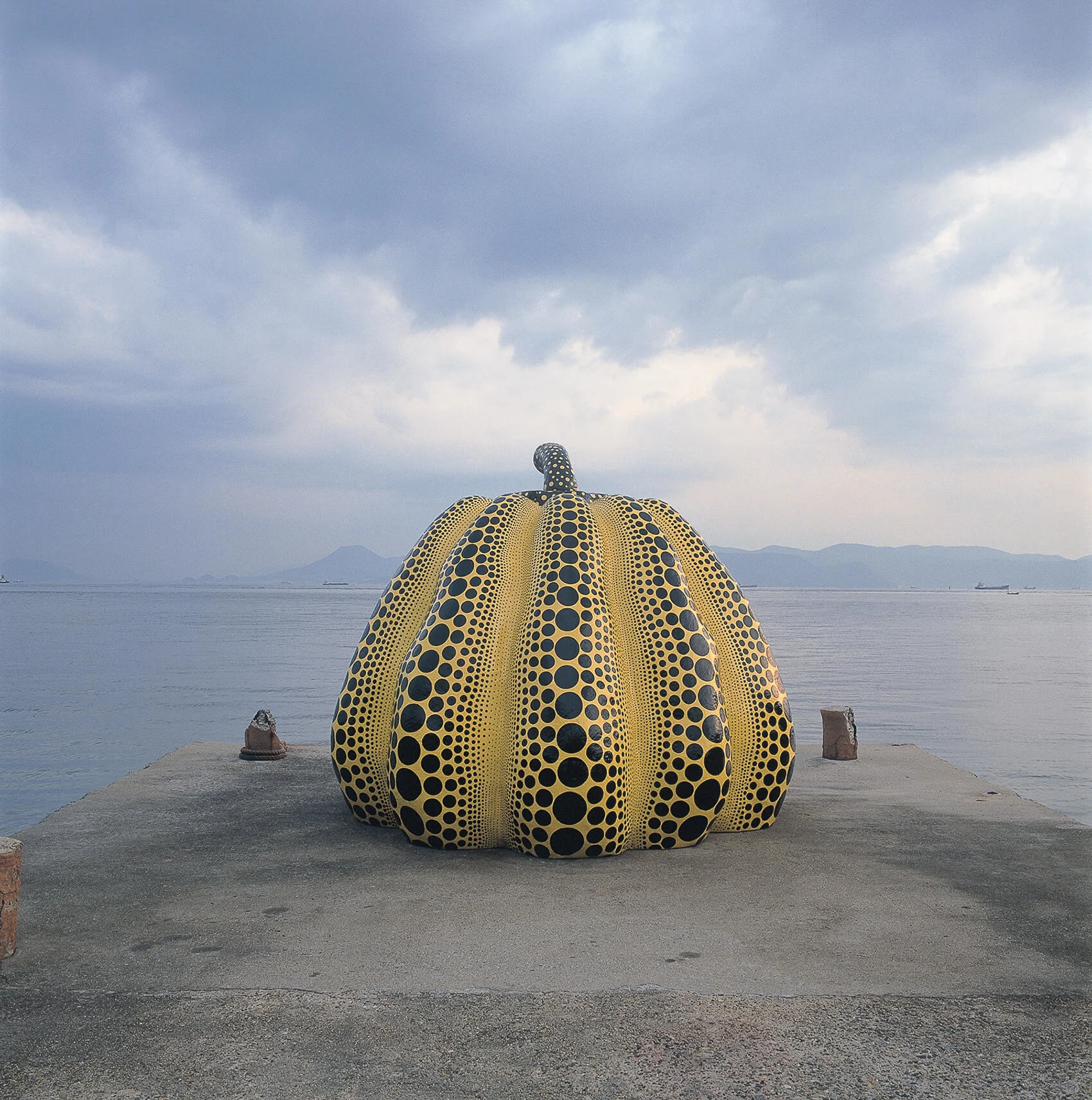

She is famous for pumpkins and polka-dots

It’s a very humble vegetable. And there’s a sense of democracy about it, in which it might be consumed by all sorts of different households.

![PUMPKIN [ERK], 2014. Acrylic on canvas. 162 x 162 cm 63 3/4 x 63 3/4 in](https://images.ctfassets.net/adaoj5ok2j3t/7IoGjSIcGEFa0QQYCspP37/58d28b10bf42822731ec0a85702d63d8/KUSA943_PUMPKIN__ERK__2014_a__1_.jpg?fm=webp&w=3000&q=75)

She paved the way for some of art’s best-known names

In New York Kusama was part of an important network of artists who were redefining what art could be. She was a close friend of Joseph Cornell and Donald Judd (whose studio was just above hers, and who was one of her first US collectors), and a contemporary of Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg.

"There are arguments that her work has anticipated some of the practices of other, better known artists," Katy says. "Like Oldenburg, in terms of her innovations in soft sculpture which pre-dated his, and Warhol, in the form of the repeat motifs on wallpaper. Her use of repetition preceded Andy Warhol's by about three years and, as a woman working in the male-dominated art world at that time, that’s really remarkable."

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant. See which of Yayoi Kusama's artworks are on display at tate.org.uk.