In 2017, Lubaina Himid won the Turner Prize, the biggest art award in the UK. It followed more than 30 years of bold and witty work that puts people of African descent at the center of our shared cultural history, which they’ve often been left out of.

From larger-than-life cut-out characters that fill entire rooms, to ceramic tableware that tells untold stories about the slave trade, Himid’s work is finally getting the attention it deserves. Tate curator Laura Castagnini talks us through some of her key themes.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant.

She was born in Zanzibar but brought up in London

Lubaina Himid was born in Zanzibar, Tanzania in 1954 and moved with her mother to London when she was just four months old. She studied Theater Design at Wimbledon College of the Arts in the mid-1970s, followed by an MA in Cultural History at the Royal College of Art, where she graduated with a thesis on Young Black Artists in Britain Today.

She went onto play a vital and vocal role in the British Black Arts Movement of the1980s. As part of a network of female artists of color – alongside Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, Ingrid Pollard, Veronica Ryan and Maud Sulter and others – she exhibited in, and curated, some of the most important exhibitions of that decade.

In 1991, Himid moved to Preston, a town in the north-west of England, about an hour north of Manchester. Drawn perhaps by her mother’s Lancastrian heritage, the complex social and industrial history of this region has played an important role in her practice.

She wants artists of color to be taken seriously

One of Himid’s key themes is the way that people of color have been represented, misrepresented and silenced throughout history. She is especially interested in tokenism in the art world and how women of color have been treated by galleries and museums.

Take The Carrot Piece, a piece which features two large painted cut-outs. A white man wearing brightly-colored clothes rides a unicycle, dangling a carrot in front of a Black woman, who looks back at him warily.

This work, Himid explains, is about how cultural institutions want to be seen to integrate people of color into their programmes, without seriously engaging with their work or the issues it raises. But the female figure in this work resists his demand for attention.

“We as Black women understood how we were being patronized,” Himid said, “to be cajoled and distracted by silly games and pointless offers. We understood, but we knew what sustained us… and what we really needed to make a positive cultural contribution: self-belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.”

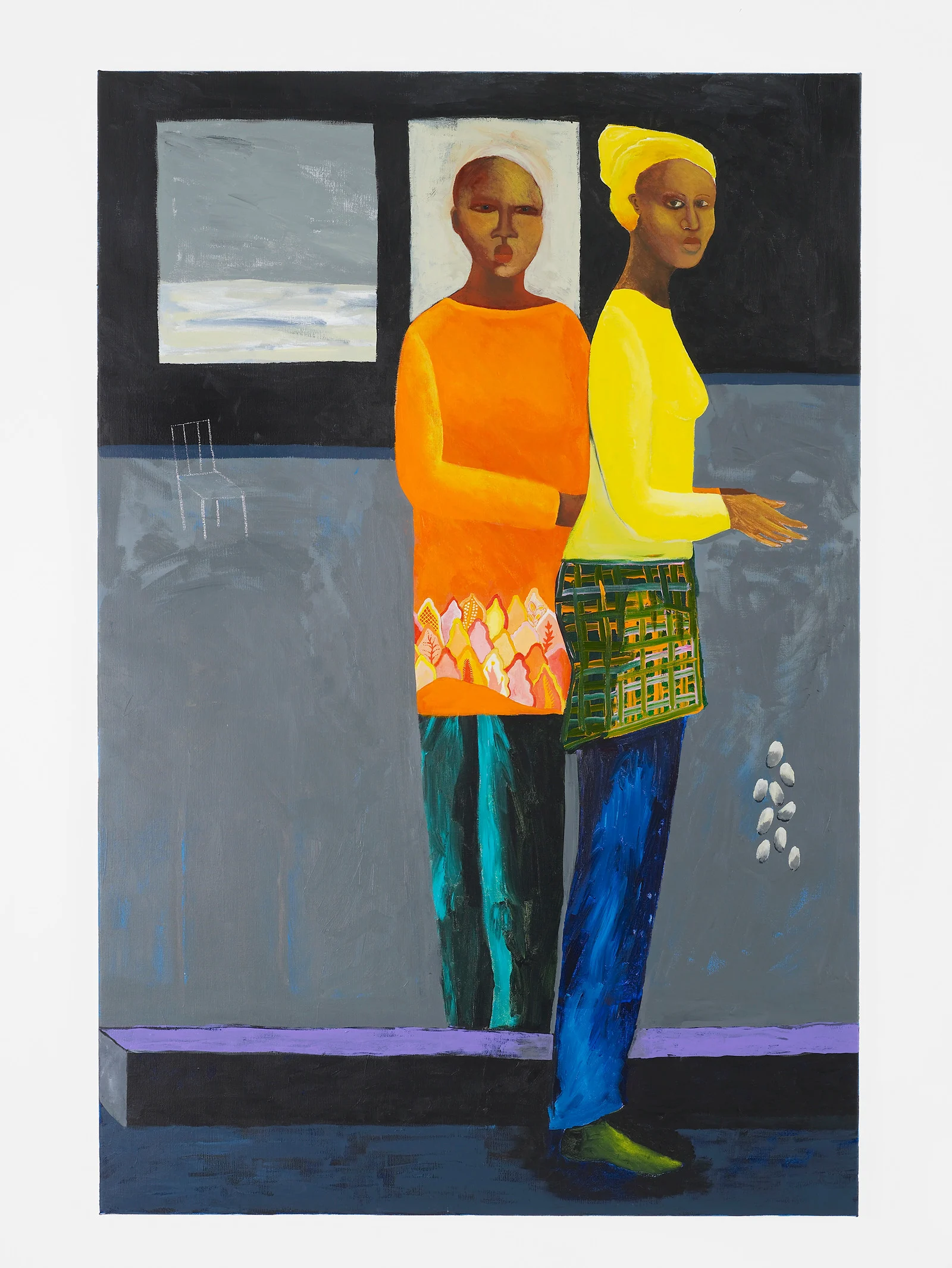

She puts people of color front and center

Often people assume these black women are friends or sisters, but it’s very possible they are lovers, and why don’t we see that?

She studied theater design which shapes the way she works

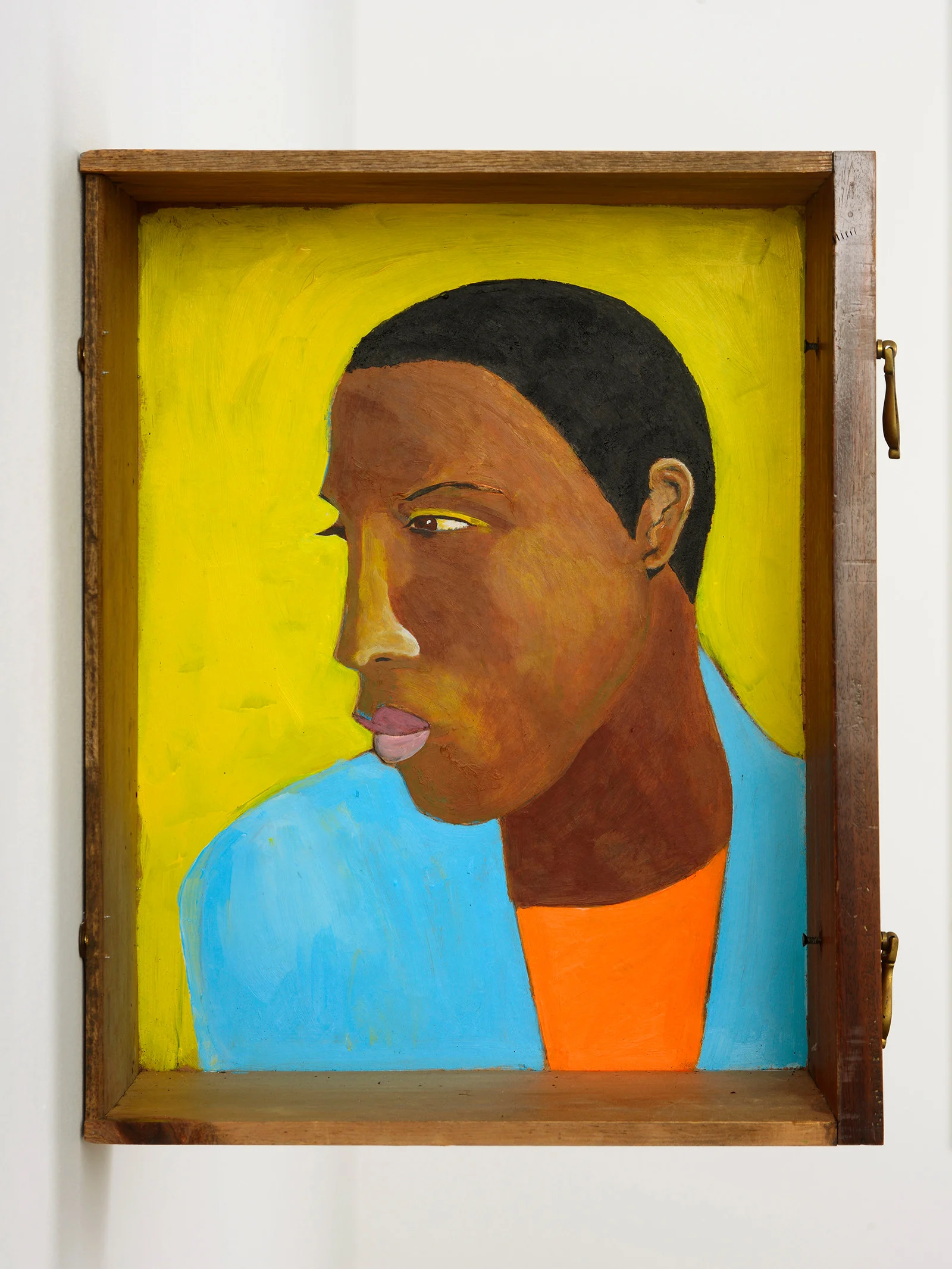

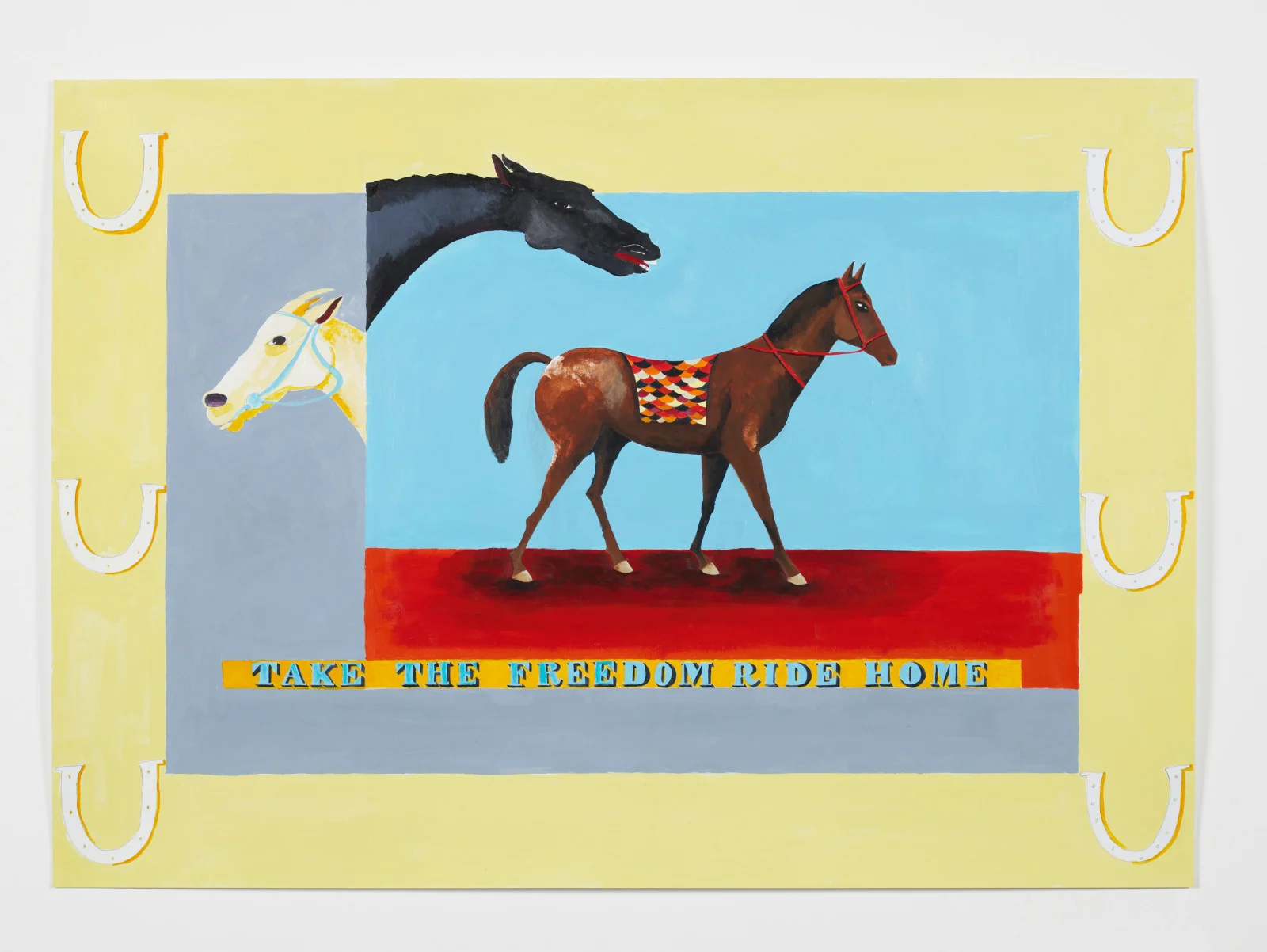

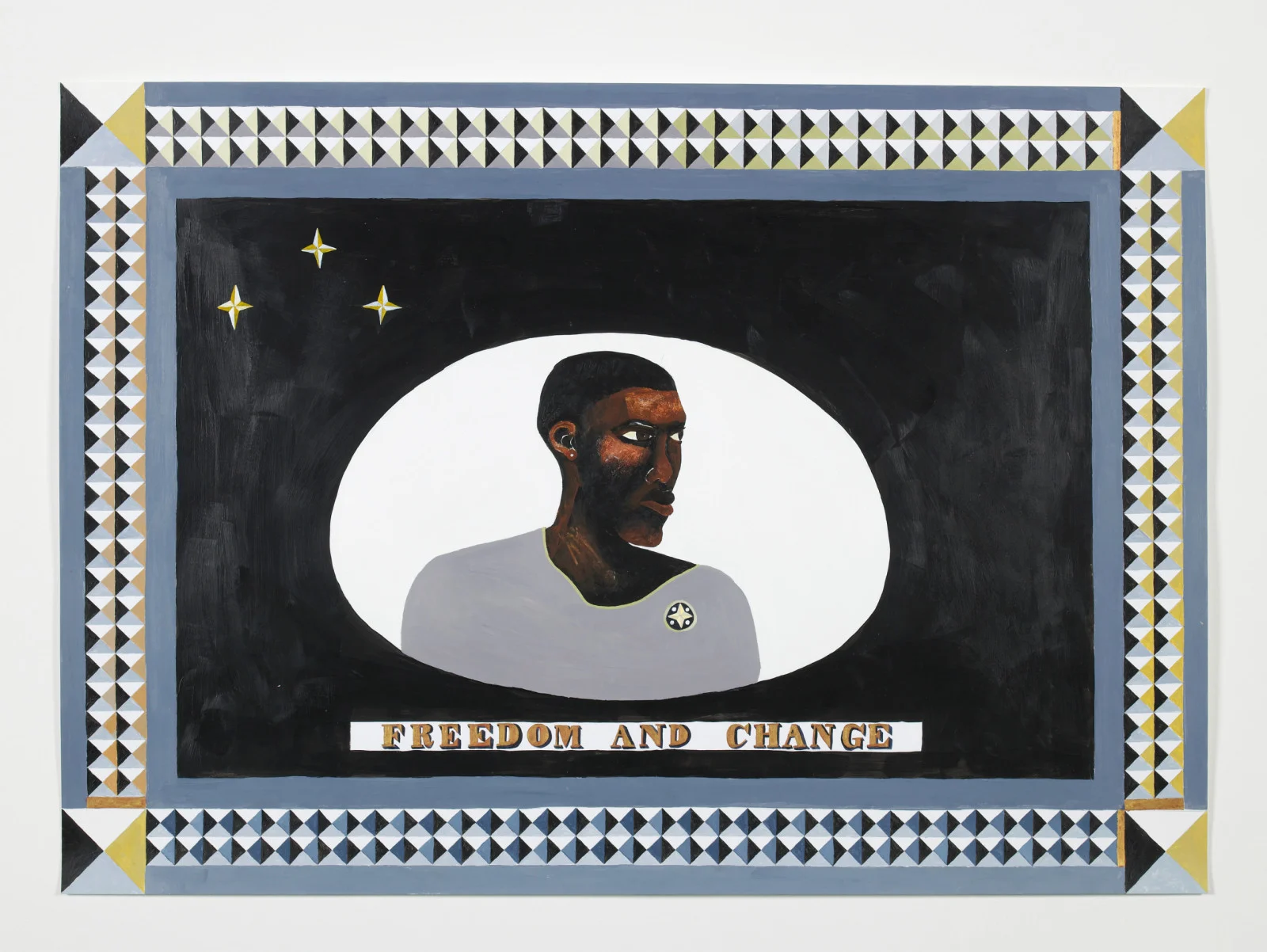

As a trained stage designer, it’s no surprise that Himid’s work feels theatrical. In her paintings she likes to use bold, rich acrylic colors for her characters, who often wear intricately textured or patterned clothes.

This influence is even more evident in her cut-outs – large, two-dimensional figures made to stand upright, and carefully positioned in a space so that they surround the viewer.

These figures are full of personality. Take her 2004 installation Naming the Money, which tells the untold stories of enslaved and servants. It features 100 cut-outs of people, each with their original African names and jobs, as well as their new names and jobs after they were sold into slavery.

Himid noticed that in 17th and 18th Century European paintings, slaves were often included to show off how rich the subjects were. They were belongings to boast about; we rarely hear their stories. So by imagining these figures’ narratives, Himid takes on the racism that has skewed our visual culture for centuries.

She pays close attention to clothes

These pieces of clothing can be a secret form of communication between women.

She is influenced by and reacts to art history

As a child, Himid frequently visited art galleries and museums and her work has been in conversation with art history throughout her career. Freedom and Change (1984) is painted on a large pink bedsheet, with the two white figures from Picasso’s 1922 painting Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race) re-imagined as two Black women leading a pack of snarling dogs away from the buried heads of two white men.

She’s also referenced the work of William Hogarth, whose engravings satirised the worst excesses of 18th Century society.

“London in the 1980s in the midst of the hedonistic, greedy, self-serving, go-getting opportunistic mayhem was a fabulous location for me as a satirist and wit,” Himid writes.

She likes to “tear up the map”

You are kind of treading uncharted waters in developing romantic, but also creative and artistic relationships between women.

Yes, but why? is a project by WePresent and Tate galleries to explain what makes some of world’s best artists so brilliant. See what Lubaina Himid artworks are on display at tate.org.uk.