Photographer, director and artist Wing Shya is one of Hong Kong’s biggest creative stars. Jaime Wolf went to meet him, watch him work and try and tap into what’s made him such a worldwide success.

Over the past two and a half decades, Wing Shya has risen to international stardom as Asia’s top fashion and commercial photographer. His high gloss, color-saturated images – like Richard Avedon’s celebrated magazine and advertising work – bake an emotional-narrative resonance into their glamour, mystery and off-kilter brand promotion.

Like Avedon, Wing has also been certified by the art world, with his work appearing in museums, galleries and installations as well as on outdoor billboards and the pages of i-D, Biba, Visionnaire, 32c, Numero, Hong Kong Tatler, and the Chinese, Italian and French editions of Vogue.

In late 2017, a career retrospective at the Shanghai Center of Photography helped contextualize this creator, whose story is often defined by his years as part of the legendary Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-wai’s team.

Wing’s prodigious output over the years across numerous media and platforms exemplifies a creative force to be reckoned with, as well as his native Hong Kong’s restless, multitasking, DIY spirit. In Cantonese, Hong Kong’s show business landscape and the figures who comprise it are referred to as “The Entertainment Circle,” a name which reflects the scene’s small size and insularity.

In Hong Kong, as well as China, Japan and many other Asian countries, star performers wear multiple hats – actors are often also pop singers and models (or vice-versa). And Wing, who originally made a name for himself as a graphic designer, has additionally distinguished himself not only as a photographer, but as a director of films, commercials and music videos.

Easily recognizable by his black lacquer glasses, and the shiny, black hair that falls beneath his shoulders, the 54-year-old is laid-back, thoughtful, curious and self-effacing: “I don’t consider myself an artist,” he says. “I’m more just a photographer.”

His creative path, he explains, proceeded according to no grand plan, winding across varied terrain and greatly affected by chance. He studied at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, where he realized how less well-off he was compared to his fellow students. This intensified his drive, while also inspiring him to experiment and find new ways to do things.

In the west, it was the height of 1990s alterna-culture, represented in part by the radical typographical innovations of David Carson and the vibrant, color-clashy design of magazines like WIRED. At the same time, China was beginning to revive the styles of its pre-Communist past, embracing a new Chinoiserie . Arriving back home, Wing blended the two in an aesthetic that both extended and updated Hong Kong’s own mongrel, neon-bathed, post-colonial British-Chinese vibe, making a mark with bold and provocative cover designs for Cantopop CDs by superstars like Karen Mok.

In 1996 he met the director Wong Kar-wai. Famous for the poetic sensibility, sensitive attunement to popular culture, and post-MTV visual style of Chungking Express and Fallen Angels, Wong would become one of the most influential filmmakers of his generation, with his 2000 film In the Mood for Love establishing him as an international icon.

Wong has always had a sharp eye for young talent, and in Wing Shya he found someone with a kindred, if still developing, sensibility who was eager to learn. The director invited Wing to take location stills for a short film commissioned by a Japanese clothing label, and then to accompany his crew to Buenos Aires, to document the production of the feature film Happy Together.

When I take a photo, at that moment, I fall in love. If I keep my distance, I keep that fresh feeling.

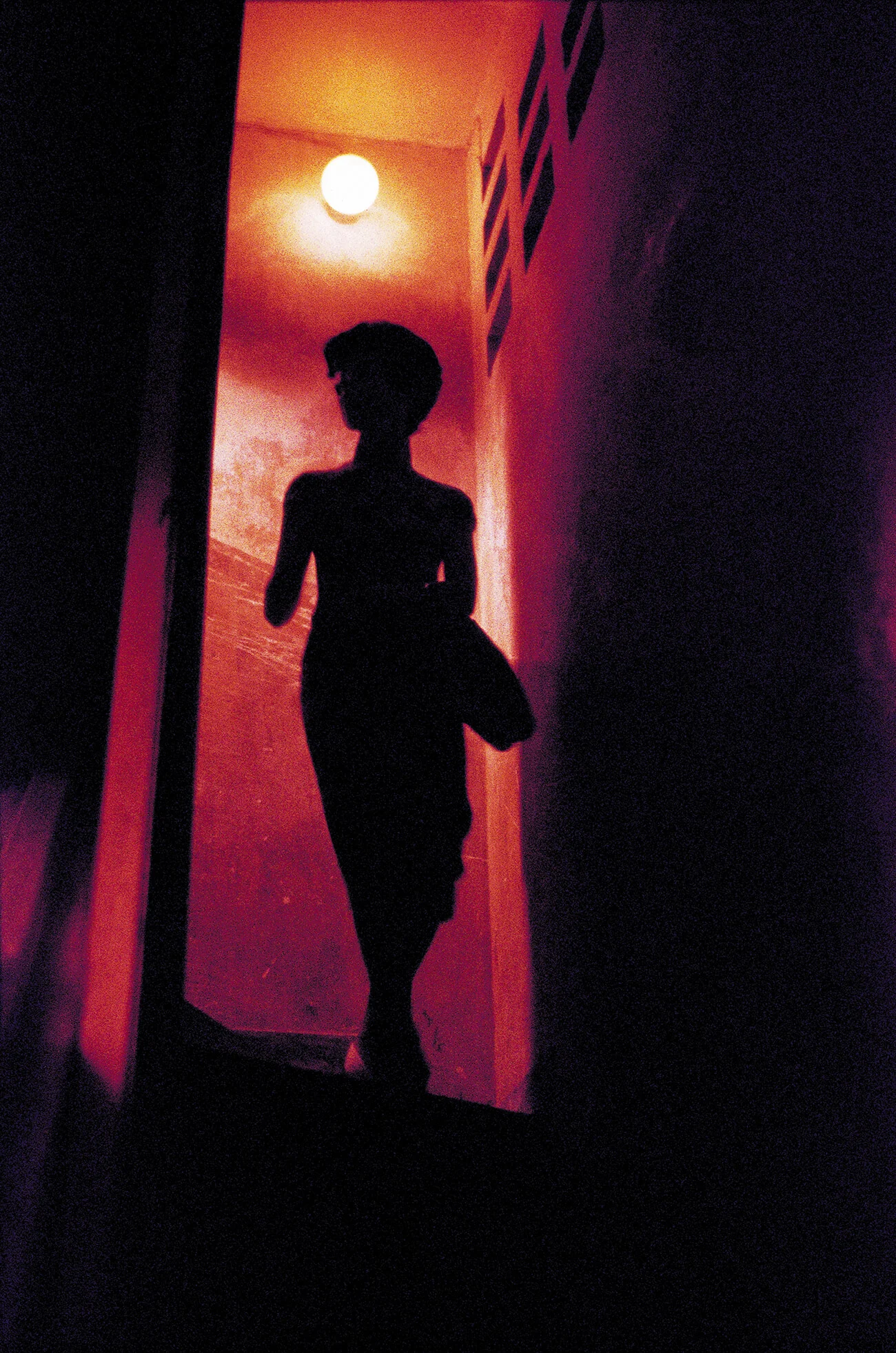

Once in Argentina, Wing received very little in the way of instruction or job description. Unlike the typical still photographer on a film, he wasn’t expected to stand next to the camera and represent the shots and compositions that would reproduce its memorable scenes and moments. His brief was more expressionistic – to represent the feeling of the film.

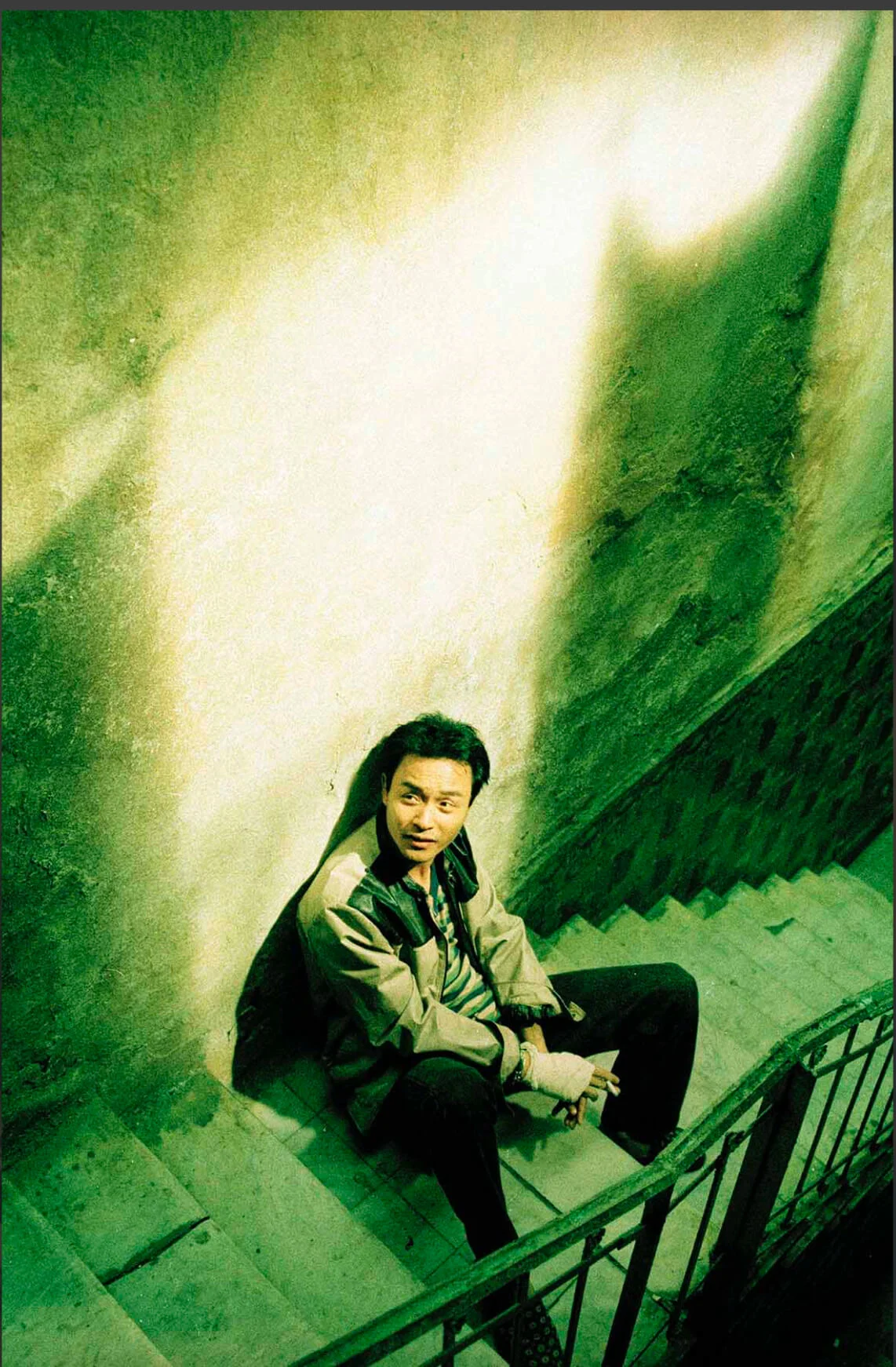

“When I started with Wong Kar-wai, I knew shit about photography,” Wing says. He simply put his 35mm camera on automatic mode and snapped away, soaking everything in and discovering how to convey the lighting, colors, textures and moods forged by Wong and his great collaborators (like cinematographer Christopher Doyle and production designer/costumer/editor William Chang Suk-ping).

He caught the stars Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung in unguarded moments, and the film’s empty sets as they were being dressed. When the film wrapped, Wing extended its worldbuilding further, assembling and designing a Happy Together photobook, featuring his stills, collages, and images overlaid with monologues Wong had written but never used. He then designed a series of striking posters for the film.

In short, Wing had become an extension of Wong’s aesthetic, expressing it via new platforms.

The photobook and posters attracted attention in Japan, and soon Wing was being offered magazine commissions by Tokyo titles like Men’s Non-no and Popeye. Wong’s actors, comfortable with Wing’s unprepossessing demeanor, started requesting him on their own shoots and recommending him to others in the Entertainment Circle.

Wing evolved a method of treating his fashion and commercial assignments almost as mini-films, where his images would present moments from a story in which the emotion was the viewer’s important takeaway. He devises dramatic scenarios, creates little scripts, gives his models – or actors, whom he employs for their instinctive understanding of his approach – characters to play.

Technically, he is spontaneous, almost naïve. “I don’t know anything about lighting or tech,” he says. “My assistants do all that. I give direction, pull references for them, and say, ‘How do you do that’?”

“Being a photographer,” he says, “you want to have the purest intention.”

Shya speaks quietly. He is open, receptive, absorbent: a good audience. It’s easy to see why superstars feel relaxed and open around him, and how he can balance theatrical, over-the-top fashion spreads with intimate documentary portraiture, such as his series chronicling composer Ryuichi Sakamoto’s return to the recording studio in 2015 after struggling with cancer.

“I don’t do the party scene,” Wing says. “I’ve never had a relationship with any of the models or actresses I’ve worked with. I care about the work more.”

“When I take a photo,” he continues, “at that moment, I fall in love. If I keep my distance, I keep that fresh feeling.”

The late 1990s and 2000s progressed in a whirlwind of shooting for high-profile magazines and a client list including A Bathing Ape, Nike, Gap, Rolex, Swarovski, Maison Martin Margiela, Louis Vuitton and Rodarte, while designing and laying out the clothier Vivienne Tam’s coffee table book, China Chic, and continuing to work as Wong Kar-Wai’s exclusive photographer and designer. He took the stills and created the promotional materials for In The Mood for Love and 2046; an arresting shot he took of Maggie Cheung at the top of a stairway was used as the official poster for the Cannes Film Festival in 2006.

But if Wing’s early work might sometimes have seemed a little too steeped in Wong Kar-wai, he evolved beyond mere imitation. Wing’s photos, music videos, commercials and short films bear their own distinctive qualities, emotional valences and signature. They are layered, lush, informed at various times by punk, cosplay, science fiction and fantasy.

In the mid-2000s, while helping his friend Alexi Tan with Tan’s debut film, Blood Brothers, Wing met writer-director Tony Chan, and together they hatched the concept for Hot Summer Days, a bright, effervescent Chinese New Year romantic comedy they went on to co-direct for the international division of Fox in 2010. They followed it up with a similar collaboration, 2011’s Love In Space.

I know it’s fake, but still… most of the people I talk to believe in love.

Wing’s relationships with so many Asian stars brought impressive young ensembles to both films, and both were huge hits in mainland China, where film had just entered its boom phase.

A self-proclaimed romantic, Wing is unapologetically attracted to feel-good comedies. He asks all the models and actors that he works with if they believe in love, and he likes telling love stories that have happy endings. “I know it’s fake,” he admits, “but still… most of the people I talk to believe in love this way.”

Wing admits that until a few years ago, around the time he turned 50, much of his drive was predicated on a desire for external validation, fame, worldly success. But now, he says, “Fame is over. I want to get back to myself.”

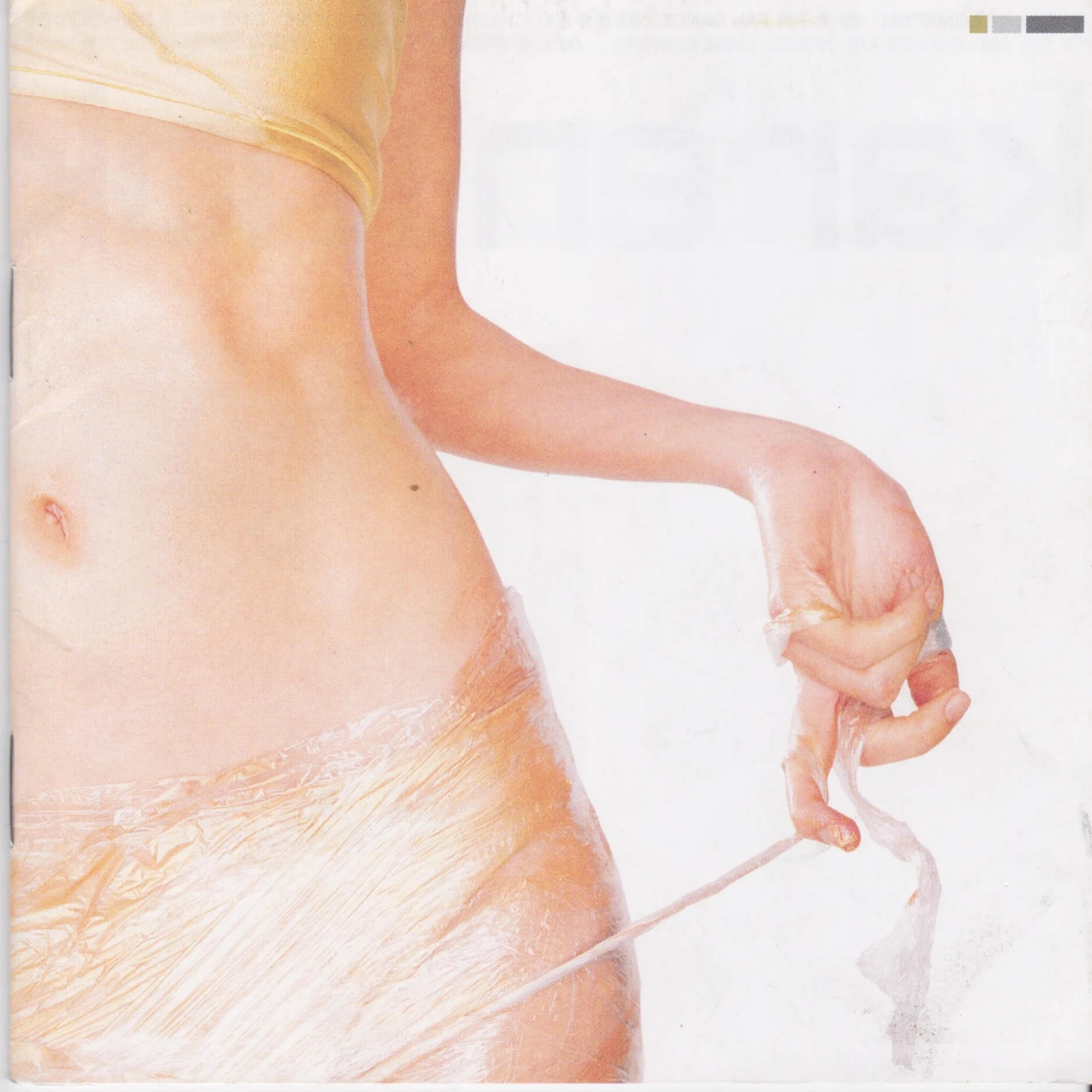

This manifests itself in a few different forms. Over the last few years, Wing has spent time in exploration and reflection, traveling to India and Peru, where he took part in ayahuasca rituals with a local shaman. At the same time, he conceived, produced, photographed and exhibited a self-funded project called Sweet Sorrow, an eerie Japanese-inflected fantasia, based on his concern for the spiritual state of Hong Kong youth.

“It started maybe six or seven years ago,” he says. “The whole world was changing because of the internet. People were posting their whole life, but it’s all fake. Hong Kong is very materialistic. These kids are suffering. There was one week when there were several suicides here. I thought, these people have no souls, just bodies. So I wanted to create something where they were all just like dolls.”

Collaborating with a crew that grew to more than 100 people, the project wound up costing more than HK $2 million ($250,000) which Wing paid himself. They spent six months just on casting, not via ordinary channels, but through Facebook and popular Hong Kong hair salons. “I would talk to the hairdressers,” he says. “You look really cool, do you have friends?”

It was unveiled at the 2018 Hong Kong Art Central Fair, with the help of gallerist Sarah Greene who calls it, “a love letter to Hong Kong.”

“Wing is a collaborator,” she explains.” He’s very altruistic and he works with other people’s energy. People will always want pieces of Wong Kar-wai”– she means both photo collectors and Shya’s commercial and fashion clientele – “but he’s worked hard to not get pigeonholed as a Wong Kar-wai sidekick.”

And what goes around comes around. Last year Wong Kar-wai came to Wing for help with the editing and post-production of a feel-good romantic comedy he was producing.

He’s busier than ever, with various film projects and a longform sci fi-fantasy-noir hybrid he’ll direct about a mysterious tattoo artist whose supernatural explorations influence the body art he creates.

When I visited Wing in Hong Kong, he was working on #EnoughPlastic, a public service campaign to reduce plastic use. Over five days, 40 of Hong Kong’s top actors, singers, models, djs and other creatives were in and out of his studio, which sits on top of an auto garage in a remote section of Chai Wan, on the western edge of Hong Kong Island.

The atmosphere was casual and Wing was confident and present, guiding each of the local personalities through comic bits that spotlighted plastic as the enemy.

After his turn, the singer William So took out his iPhone and showed some of Wing’s crew members a clip from the Chinese New Year comedy, I Love Hong Kong 2012, in which Bob Lam Shing-pun plays a manic fashion photographer, dressed in black, like Wing, with the same black glasses and a long wig.

It’s typical broad Hong Kong comedy, showing the photographer distracted by his buxom assistant, and barking rapid, nonsensical directions at his subjects. The contrast between this cartoon rendition and the real thing in the room was absurd, but also hilarious. The affection everyone had for Wing proved that sometimes, his subjects really do believe in love.