In 10 short years, Toyin Ojih Odutola has risen to become one of the brightest stars of a generation of young artists. A favorite with critics, collectors and museums alike, her sublime portraits render blackness at once universal and unrecognizable. But for Toyin – reared on comic books and anime – merely representing blackness isn’t enough. She knows a compelling story, coupled with beautiful drawings, can create pure magic. Speaking over Skype from her New York apartment, Toyin tells writer Allyssia Alleyne how she’s fusing the narrative and the figurative to escape the limitations of expectations.

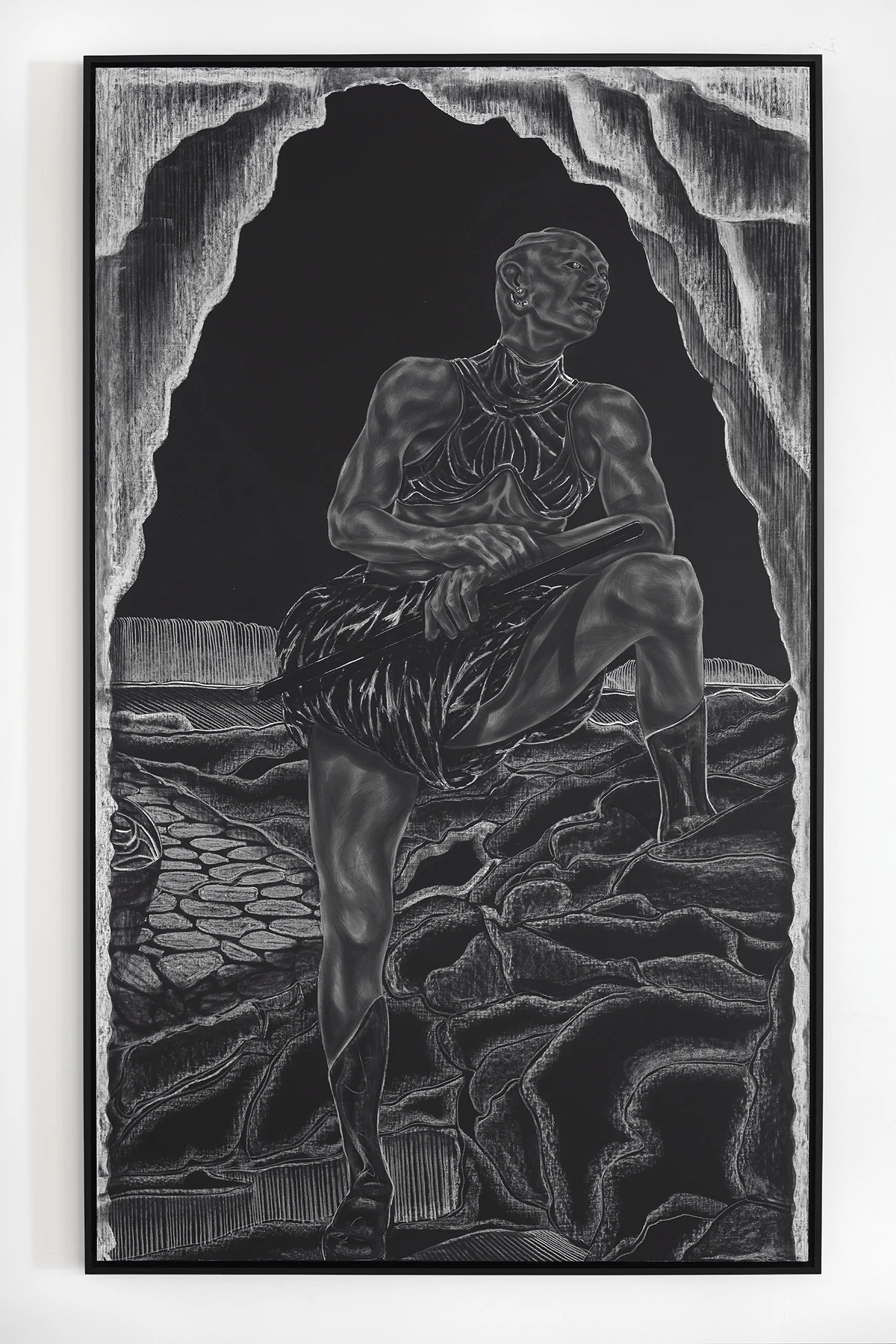

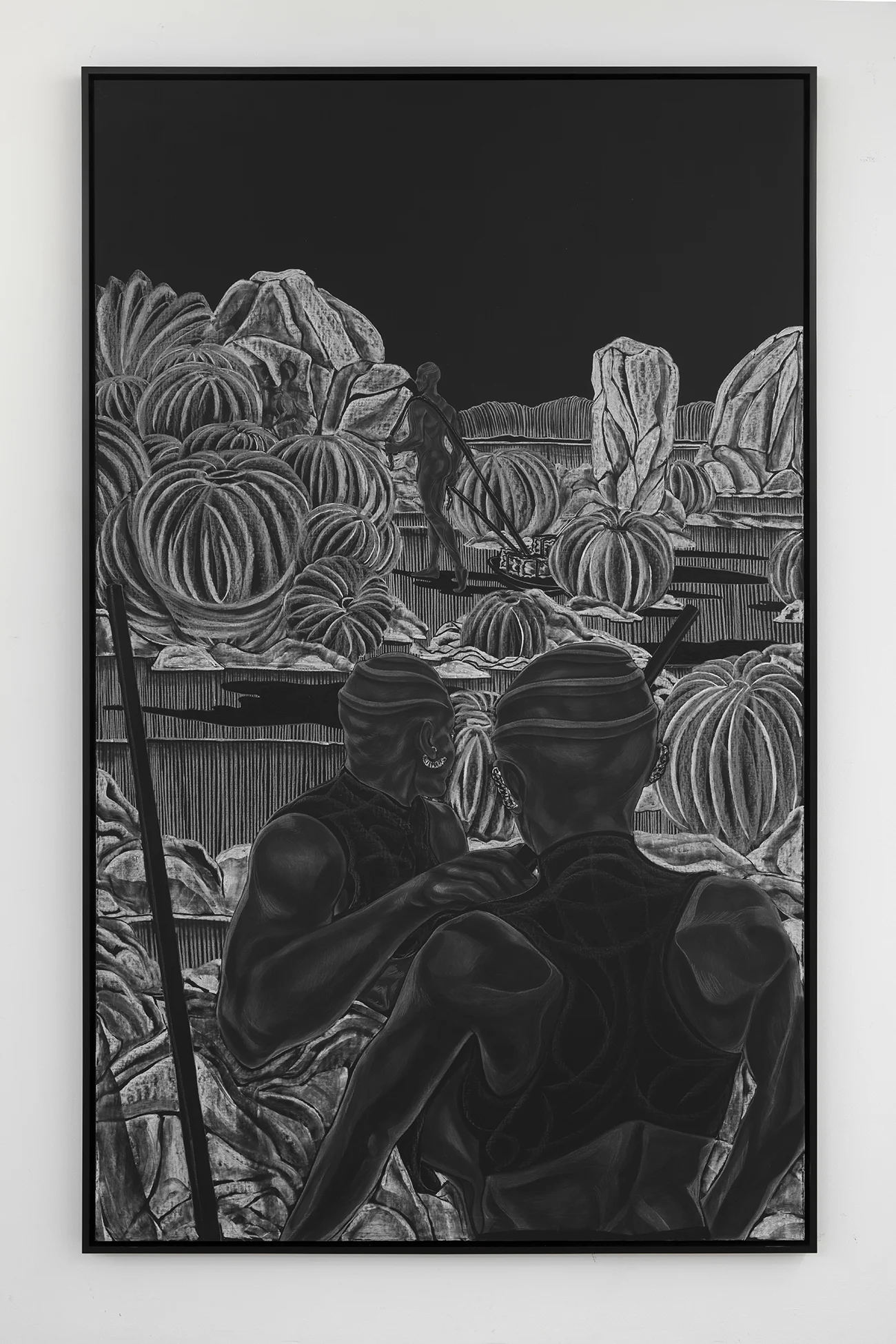

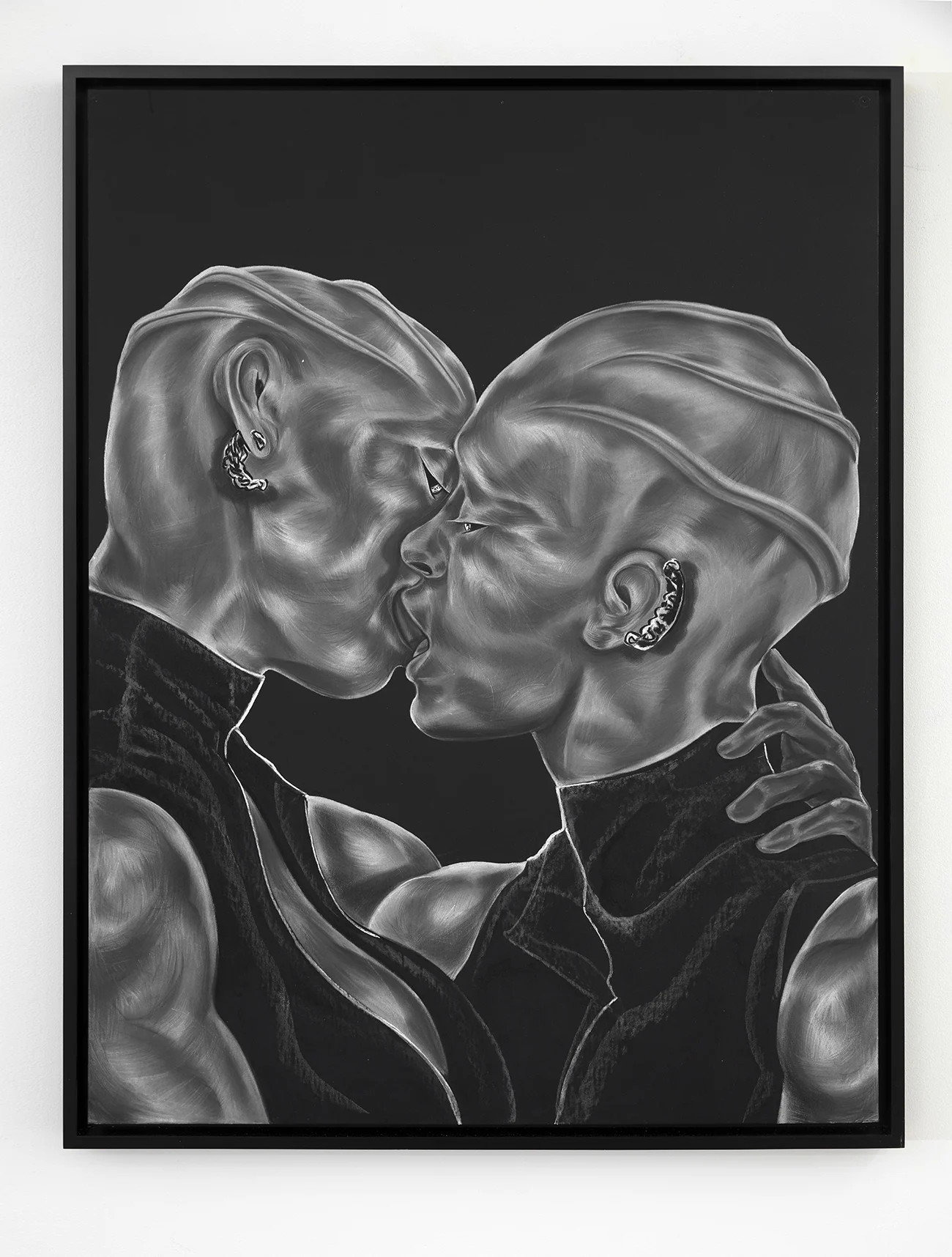

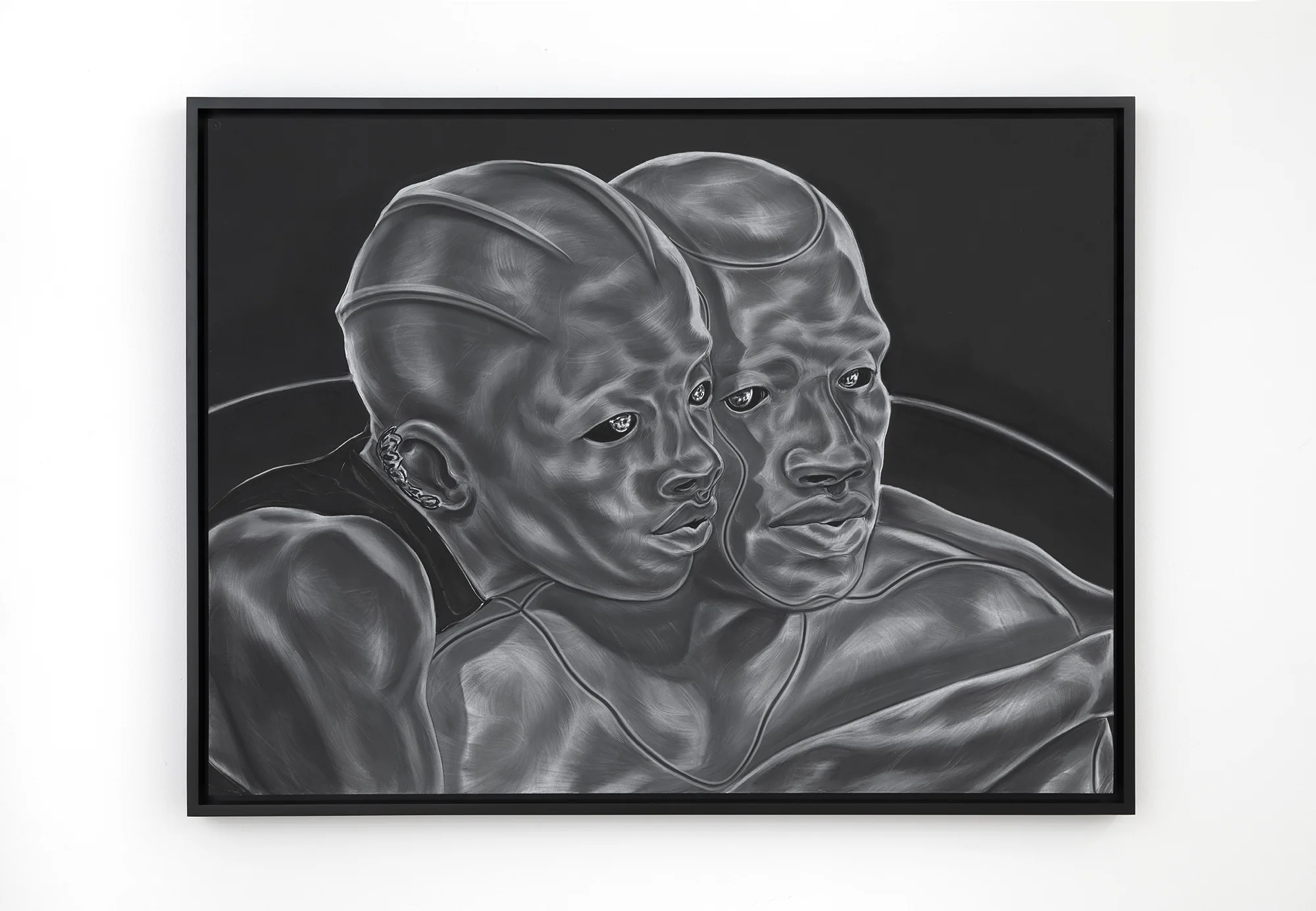

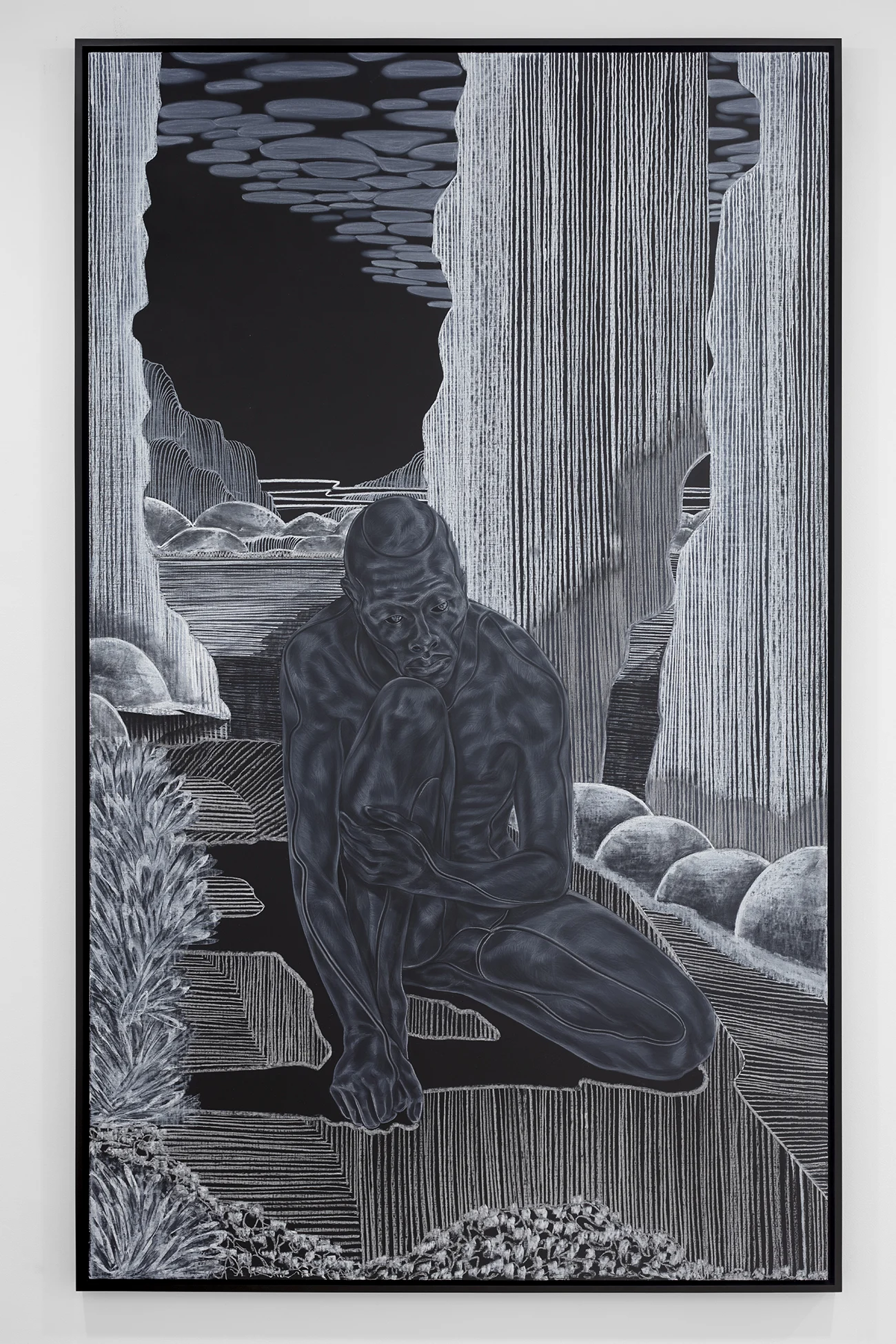

Nigerian-American artist Toyin Ojih Odutola has a beguiling way of depicting the black figure. With pastels, pencils, chalk, charcoal and ballpoint pen strokes, she imbues afros, curls and dreads with almost kinetic energy. Terrains of skin shine like polished bronze, undulate in waves, and explode from the page like white light through a kaleidoscope. Body language and knowing eyes, always seemingly looking at something beyond the frame, suggest interiority, complexity and a life that continues once the viewer has moved on.

Her distinctive style, modern and mysterious, has made her one of the most acclaimed young artists working today, with solo exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia, and San Francisco’s Museum of African Diaspora behind her, and shows in the United Kingdom and Denmark ahead of her when the world comes out of lockdown. But lately, the figurative has left her wanting. Just presenting Black people existing (still noteworthy in the predominately white world of art institutions) is no longer enough. “(At the start of my career), what I was drawing was very much about the black figure occupying space, which was important at the time – it was needed. But somewhere along the line I realized I'm not really so much concerned about just having a black figure occupy space. I'm interested in stories,” she says.

It’s with this in mind that, a few years ago, Toyin shifted her focus from the figure to the narrative in an attempt to bypass and subvert the expectations people place on works by artists of color – and on the artists themselves. Once aware of her background, she says, critics and viewers seemed to find it impossible to divorce her biography from her work, looking for traces of Nigeria and the South, intergenerational trauma and diasporic dissonance. “It's a limitation to the artist’s creative capacity to bypass the vividness and the expansion of their imaginary…I'm not saying that someone can't paint or draw or sculpt or perform their life story through their art (and) create really engaging, important, beautiful, brilliant work. What I'm saying is that there needs to be more ways of doing that,” Toyin explains.

I realized I’m not really so much concerned about just having a black figure occupy space. I'm interested in stories.

Her first large-scale exploration into the narrative started in 2016, when she started the initial chapter of her trilogy of series comprising “rarely exhibited portraits” from the private collections of two aristocratic – and fictional – Nigerian families . Casting herself as the family’s deputy private secretary in her artist statements, she staged shows organized by Lord Temitope Omodele and his husband, Lord Jideofor Emeka, 19th Marquess of the UmuEze Amara, in partnership with the hosting institutions. With drawings inspired by traditional portraits of European elites, as well as eyeroll-worthy Instagram posts of the good life, she weaves an intriguing, contained story that challenges stereotypes around Africans, and Black people more broadly, in art.

“All those (exhibitions) came from a story, and that came from a need that I had to completely sever myself and my biography from the read of the work. The story just gave me so much freedom, and when you have that kind of freedom, you really can do whatever you want… It sounds pretty common, but as an artist of color, there's so few allowances for that.”

Toyin was born to a Yoruba father and Igbo mother in Ife, Nigeria. At five, she moved with her mother and brother to California to be with her father, who was then teaching and researching chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Four years later, the family decamped once more, this time for Huntsville, Alabama.

Growing up, stories were Toyin’s life. A self-professed nerd growing up in the ’90s, she devoured comic books and became obsessed with anime series like Outlaw Star, Gall Force and 8 Man After, and originally aspired to be an illustrator. (“I do not have the balls to be an illustrator,” she confesses. “It takes an incredible amount of wherewithal and design know-how.”)

As she got older, she was exposed to the works of Black writers who “(showed) more options for black stories,” which left an indelible mark: She has James Baldwin’s signature tattooed on her right hand and Octavia Butler’s (“The OG”) on her left, and fills the conversation with Toni Morrison references.

Toyin also grew up with the stories America tells itself about its past and the horrific suffering endured by African-Americans for centuries. But while she acknowledges and appreciates stories related to this history are important, she isn’t inclined to revisit them in her own work. “I just cannot in my heart – as someone born in Nigeria, raised there, brought to the US at a young age, raised in the American South – just depict Black pain. I'm sorry, I just can't do that. I don't feel comfortable doing that. I want to create freeing spaces,” she says. “That horror somehow connects us globally, unfortunately. But it doesn't have to be (all) we talk about; it doesn't have to be an endpoint or a final read.”

Toyin had planned to unveil her most ambitious story at the Barbican in London this past March. A Countervailing Theory, which has been postponed indefinitely due to coronavirus lockdown measures, was meant to unfurl in 40 large-scale drawings along all 90 meters of the Curve Gallery’s walls like a Chinese handscroll. Accompanied by a soundscape from the DJ and artist Peter Adjaye, they would tell a devised myth set in an ancient matriarchal society in Nigeria’s Jos Plateau, where women rule over humanoid men they create to serve them.

I also don’t mind that the viewer could bring in their own experiences, their own ideas.

From the start, writing was integral to her process. After months of research into the structure of myths, she began fleshing out the general narrative concept, allowing her imagination to conjure new twists and characters beyond what she’d originally conceived. (Though author Zadie Smith once fawningly told her she “writes like a writer,” Toyin is sincerely self-deprecating about her abilities: “The way that I write is very clinical…I write to help me draw.”) When the story was fully formed, she transformed from writer to storyboard artist, pairing thumbnails with text – enough to make sure she was capturing the necessary detail to get a full story across without relying on the viewer’s preexisting understanding of specific references and callbacks.

“That will be my bread and butter as an artist: You can look at this picture and kind of surmise what’s going on,” she says. “I also don’t mind that someone could bring in their own experiences, their own ideas, their own whatever they might project onto those pictures as well, but what I have to do, as a creator, is to get that picture tight.”

With the series done and awaiting its grand reveal, Toyin is anxious to see how people respond to and interpret the overarching narrative, as well as the themes planted beneath the surface. After all, what’s a good story without a little subtext?

“I want people to engage with my work in a way that’s not just, ‘Oh look, what a pretty picture on a wall. Isn’t Toyin a genius?’ I’m not interested in that brand of art-making or artist,” she says. “I’m really interested in what a picture can tell you, and it can tell you a lot if you let it.”