Karrabing Film Collective’s commission for Serpentine’s Back to Earth commission centers on Art Residency for Ancestors, a project to fund a green residency and open-air gallery on a protected compound, allowing the group to bypass Western museums and galleries to support Indigenous creatives. Comprehensive digital mapping of rock weirs and shell middens will also take place, with the ultimate goal of creating a cultural heritage area around the Mabuluk region.

Words by Ravi Ghosh.

Karrabing Film Collective are raising funds for their Art Residency for Ancestors, to protect the totemic, historical ecology and geography of the south side of the Anson Bay, Northern Territory, Australia, including panoramic totemic beings, a vast network of rock weirs (fish traps), and towering shell midden. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

Karrabing Film Collective don’t tend to make zombie movies, but with The Family, they’re giving it a go and letting themselves have some fun. The film opens with a scene of indigenous children digging yams and playing in lush green overgrowth. One kid howls in the background, pretending to be a dingo. A zombie emerges slowly from behind a log, its skin crusted with an oozing white substance, extending a clawed arm toward the children; when they notice, the figure quickly recoils. The children laugh and continue to play, before following the creature to its lair of rusted cars, plastic debris and tarnished woodland. By the end of the film, they’ve killed the monster. What opened as a fairly innocent scene has turned into a commentary on the toxic dangers of unbridled Western consumption.

“You see this scene of indigenous people doing things that stereotypically people would think, ‘Oh, culture and tradition,’ or, ‘Look! Beautiful indigenous people in their natural habitat,’” laughs Elizabeth Povinelli, a Karrabing member who plays the grotesque creature. Subverting expectations of Indigenous life is an important basis for Karrabing’s films, but in inviting the metaphor of zombie-as-Berragut (the group’s term for white people), The Family also deepens their interrogation of the ecological breakdown, Indigenous destruction and cultural erasure that settler colonialism has caused across Australia’s Northern Territory and elsewhere.

Karrabing shoots their films in a democratised way, using iPhones and employing a flat creative hierarchy.

Karrabing comprises five Indigenous family groups born and raised in the Belyuen Community, around 20km southwest of Darwin, and now residing in regions across the Anson Bay. When Elizabeth arrived there straight out of college with a philosophy degree in 1984, many of the group’s current members were between seven and 12 years old, their ancestors having been interned on the lands since the 1940s. She was asked by the parents of the Karrabing to become an anthropologist to help them with a land claim. She has worked alongside her Indigenous colleagues ever since, on legal, political, cultural and social projects.

In the 1970s, the Australian government shifted its policy of Indigenous assimilation – “an explicit white nationalism,” Elizabeth says – towards a gradual process of intended multiculturalism. But by overlooking Indigenous values when pursuing land redistribution, the floodgates opened to exploitative mining and industrial testing on lands of importance to Indigenous communities. Senior Emmiyengal Karrabing member, Rex Edmunds argues, “White people make us weak by saying that two or three people are the traditional owners so the other Indigenous people in the area .” The Land Rights Legislation which was supposed to be about recognizing Indigenous law, was used “to divide people and make them fight each other.”

Violence towards the group erupted in 2007, when the government reneged on its promise of secure housing and passed the Northern Territory National Emergency Response – known as The Intervention – which imposed lifestyle restrictions, reorganised educational access, abolished development programmes, and, crucially, removed cultural considerations from criminal proceedings.

It was from this trauma that the Karrabing Indigenous Corporation came into being. The name refers to when the vast coastal tides are at their lowest, in contrast to Karrakal. Cecilia Lewis, an Emmiyengal member of the Collective, describes these two tides as “joining up” the different languages, families, totems and stories of the Karrabing into “one mob.” Or as Linda Yarrowin, also a senior Long Yam Emmiyengal woman puts it, “we have separate-separate lands but they are all connected.”

By overlooking Indigenous values when pursuing land redistribution, the floodgates opened to exploitative mining and industrial testing on lands of importance to Indigenous communities. ”

“It articulated the field of actual differences into the unity that was potentially there,” Elizabeth explains. Each family is known as a “mob,” with its own dialect and customs, but unified by a shared spiritual heritage along the Bay. Karrabing, says founder and senior Indigenous member Rex Edmunds, “means tide out – and when it comes in, coming together.”

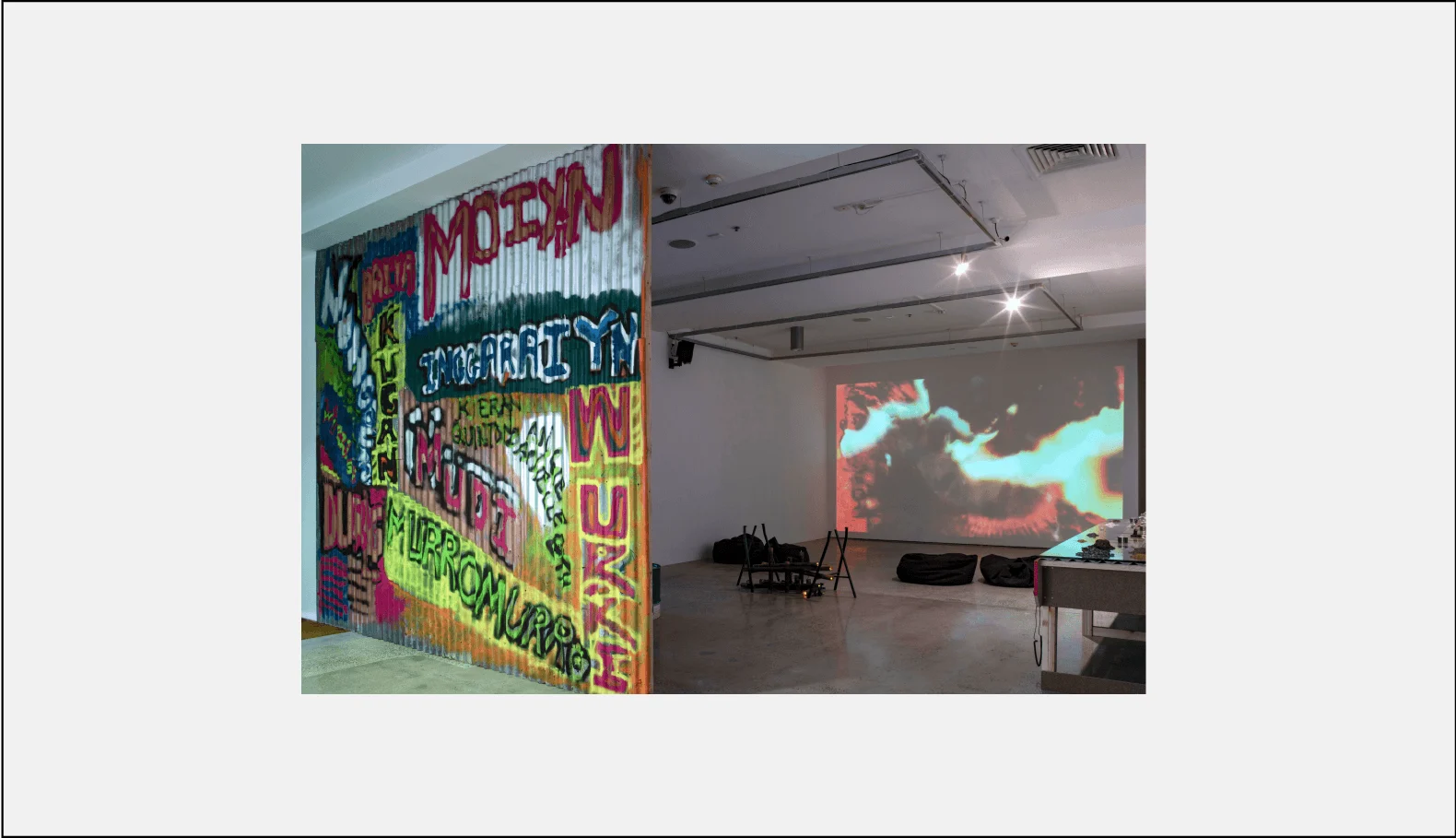

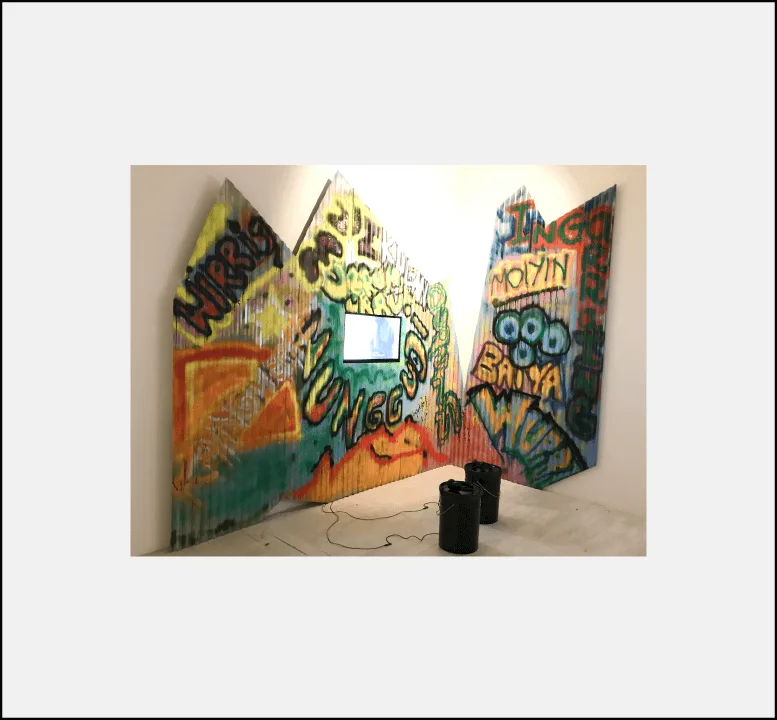

Alongside The Family, Karrabing’s Back to Earth commission centres on Art Residency for Ancestors, a project to fund a green residency and open-air gallery on a protected compound, allowing the group to bypass Western museums and galleries to support Indigenous creatives.

Comprehensive digital mapping of rock weirs and shell middens will also take place, with the ultimate goal of creating a cultural heritage area around the Mabuluk region.

In the aftermath of 2007, Karrabing considered using digital technologies to raise awareness about settler colonialism: tourists would be able to scan QR codes whenever they entered formerly-Indigenous lands, which would take them to a Karrabing website with explainers, activism and support links: a way for the group to articulate the experience of becoming refugees in their own country. But film felt more appropriate, Elizabeth tells me. A medium more able to tease and probe the intricacies of Indigenous existence without sacrificing agency or, crucially, the enjoyment of the making process.

Karrabing shoots their films in a democratised way, using iPhones and employing a flat creative hierarchy. Three early films: When the Dogs Talked (2014), Windjarrameru: The Stealing C✱nt$ (2015), and Wutharr: Saltwater Dreams (2016) capture emotional responses to the “radical abandonment” of the Intervention in the allusive manner still favoured in their work. In The Jealous One (2017), clips of a phone operator from the Australian land authorities fade in and out of Rex Edmunds’ narration. “Good-day, state control over indigenous lands. Can I help you?” she asks, before becoming irate with an Indiegeous person querying land ownership rules. These are stories of containment, confusion and constriction – the partitioning of lands along nationalist and bureaucratic lines.

Dogs stages a conversation about a mystical dog figure searching for fire to cook yams. “Do you believe in your mother’s dreaming?” Cecilia Lewis asks cryptically as she cooks her daughter, Telish Bianamu, Wadjigiyn member of Karrabing, a fried egg. Later on, a group crosses a line of barbed wire to examine large holes in the land, hiding when a plane passes overhead and mocking one another for their knowledge of ancestral stories. All the while, the conversations seem to destabilise non-Indigenous ideas of species, land and belonging, gesturing towards a spiritual allegory but without ever confirming it.

Similarly in Wutharr, a broken boat motor opens a three-way debate on the supernatural forces which might come to their aid. Again references to ancestors suggest entities beyond control or comprehension. Trevor Bianamu, a senior Sea Serpent (durlg) Wadjigiyn Karrabing member says, “When I was walking through the bush, I saw evidence of our ancestors everywhere.” “The ancestors must have broken this motor,” one man says, while Linda Yarrowin suggests putting faith in the Lord will restore it (a strand of Christianity is present within Karrabing). A conversation between her and the ancestors breaks down the assumed distance between them: “If you call out to us, we will help you,” an unseen ancestral voice replies calmly.

Karrabing’s work makes visual a set of deeply held beliefs, which, although can be attached to Western conceptions of ancestry, country, land and time, cannot be fully explained by them. “The present, past and future are not different temporalities; they’re all materially in the same time,” Elizabeth explains. This is a useful framework for understanding Karrabing’s ties to ancestry: a symbiotic, reciprocal relationship which relies on nourishment and care, which is closely entwined with the land where elders go to rest. So when people don’t look after their country, it withers and dies out as the ancestors withdraw.

“We don’t think our ancestors are in the past,” Angelina Lewis, Cecilia’s sister says. “They are in the past, present and future. They’re still here with us.” Thus their film and installation art works do not merely represent their world, but are in active communication with it. As Karrabing member, Natasha Bigfoot Lewis, who has a Barramundi Totem put is in Carriageworks (2020) “We’re giving back to the ancestors. Giving back what they gave us in the beginning.” Ancestors, like all creatures, require regular attention from the living to uphold shared harmony.

We don’t think our ancestors are in the past. They were there when we weren’t there, but they’re still here with us.

Dreamings (durlg) are closely linked: totemic places which hold ancestral significance to different members of the group – for example a specific reef or beach – and which exemplify the interrelation of Karrabing’s more-than-human belief system with local ecology. “As floating nets and garbage collect on the reef, it is struggling to stay in place the way we are,” Rex Edmunds explains of his Barramundi dreaming.

“We’re doing these films to extend, thicken and create these generational archives of knowledge – not just that, but a practice of a different sense of time and of the more than human world that we live in,” Elizabeth continues. The art residency is a gesture of respect and goodwill which, Karrabing hope, will last for generations. “When you go back to your country and set up film and art, that country comes alive again,” says Karrabing member Linda Yarrowin in Carriageworks. “Because the ancestors know that family have come back to their country.”

Karrabing’s work makes visual a set of deeply held beliefs, which, although can be attached to Western conceptions of ancestry, country, land and time, cannot be fully explained by them.

Karrabing films and installations works with and against Western genres inside art and university worlds. A New York Times review of their 2018 MoMA PS1 showcase noted that while the early films were “more documentary or informational” they quickly moved to a “more experimental and ecstatic” realm, combining “traditional myth and storytelling with new film and video technologies to convey a vision that translates far beyond the country’s borders.” That same year, Elizabeth selected several keywords to illustrate the Western gaze which Karrabing experiences, including “ethnography/documentary, training, collaboration and transparency.”

All these descriptors miss the fundamental point of Karrabing’s practice, Elizabeth argues. She sees Karrabing as working against the “general demand...made of Indigenous collectives to produce narrative as forms of representation rather than as filmic innovation.” In other words, onlookers struggle to reconcile that the group makes films because they enjoy it and because of its value to their ancestors, rather than a desire to offer Westerners a ‘transparent’ picture of Indigenous life. If follows that attempting to decipher Karrabing’s intentions via traditional ideas of genre and creative categorisation is futile, as is the desire to judge the 'authenticity' of the world they inhabit.

This dissonance then becomes its own form of meaning, Elizabeth concludes: it is this interplay between “what a liberal, educated, Western audience has been tutored to know about Indigenous existence and what Karrabing members want to say about who they are that all Karrabing films make visible.” As Rex Edmunds says, “When we go into art, it’s in order to get people to understand in a different way. A new dimension. So we went from film to art; and art includes Dreaming sites, it tells our story. Then when we go back to the country, we see a lot, we sort of feel spirits there.”

The Art Residency for Ancestors may seem like a withdrawal from the push and pull of Western cultural discourses, even as their work becomes more widely known, garnering international prizes such as the Eye Art and Film Prize. But for Karrabing, their films and artworks have always been tied first and foremost to deepening their ancestral relationships. Creating a space in which their artworks and films are placed on their lands and in direct relationship with and in support of their ancestors, even as they continue to circulate publicly, is a culmination of their artistic vision.

But there remains a vulnerability in their work. The Family is ultimately a message of warning: of the increasing pollution of lands and the omnipresent threat of another Intervention-style event. The divide and conquer tactics of the Australian state loom in the memory, but there is the acknowledgement that settler colonialism – and with it, climate breakdown – cannot be reversed, and that resistance and reform are the only options. Cecilia Lewis’ words echo far beyond their latest film, How we make Karrabing (2020): “They can try and separate you, but you always have to remember where you belong, where your country is. That’s what makes you strong.”

Explore more

M

Matariki Williams, Karrabing Film Collective tackles the cultural and environmental devastation of settler colonialism. ArtNews, Art in America. May 6, 2020.

S

Shona Mei Findlay and Mik Gaspay, Interview with Karrabing Film Collective. KADIST. 2019.

T

Tess Lea, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Karrabing: An Essay in Keywords. Visual Anthropology Review, Volume 34 Number 1. Spring 2018.

U

UN Projects, Growing up Karrabing: a conversation with Gavin Bianamu, Sheree Bianamu, Natasha Lewis Bigfoot, Ethan Jorrock and Elizabeth Povinelli. UN Magazine Issue 11-2. 2017.

Groundwork is a collaboration between the Serpentine and WePresent. It explores the extensive research behind five artists’ proposals for Back To Earth, Serpentine’s multi-year project focused on instigating change in response to the climate crisis.

Groundwork will act as a series of accessible mini-encyclopaedias with all the references artists use to develop a final artwork. They will go behind-the-scenes on the research the artists have done as part of their project for Back to Earth, in a bid to reveal their processes and inform how the viewer might see the project as a whole when completed. It will involve diving deep into the research of artists such as Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Vivienne Westwood, Karrabing Film Collective, Himali Singh Soin and Tabita Rezaire.

Karrabing Film Collective are raising funds for their Art Residency for Ancestors, to protect the totemic, historical ecology and geography of the south side of the Anson Bay, Northern Territory, Australia, including panoramic totemic beings, a vast network of rock weirs (fish traps), and towering shell midden.In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

Back to Earth is curated and produced by Rebecca Lewin, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jo Paton, Lucia Pietroiusti, Holly Shuttleworth and Kostas Stasinopoulos.