After years spent exploring the Earth's poles, Himali Singh Soin returned to India for a different type of expedition. Tracing a lost Cold War relic “that could still be ticking somewhere,” she created static range – a cross-continental transdisciplinary project for Serpentine's Back to Earth project. She talks to Ravi Ghosh about mountains, myths, and the nuclear sublime.

Himali Singh Soin has chosen to highlight the secular non-profit Live to Love. The grassroots movement empowers communities to serve as guardians of the Himalayas and its people, with the goal to create sustainable solutions for the future of each region, and foster a culture of empowerment and of resiliency. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

To experience static range fully, hit the audio button above and hover over the stamps in the article.

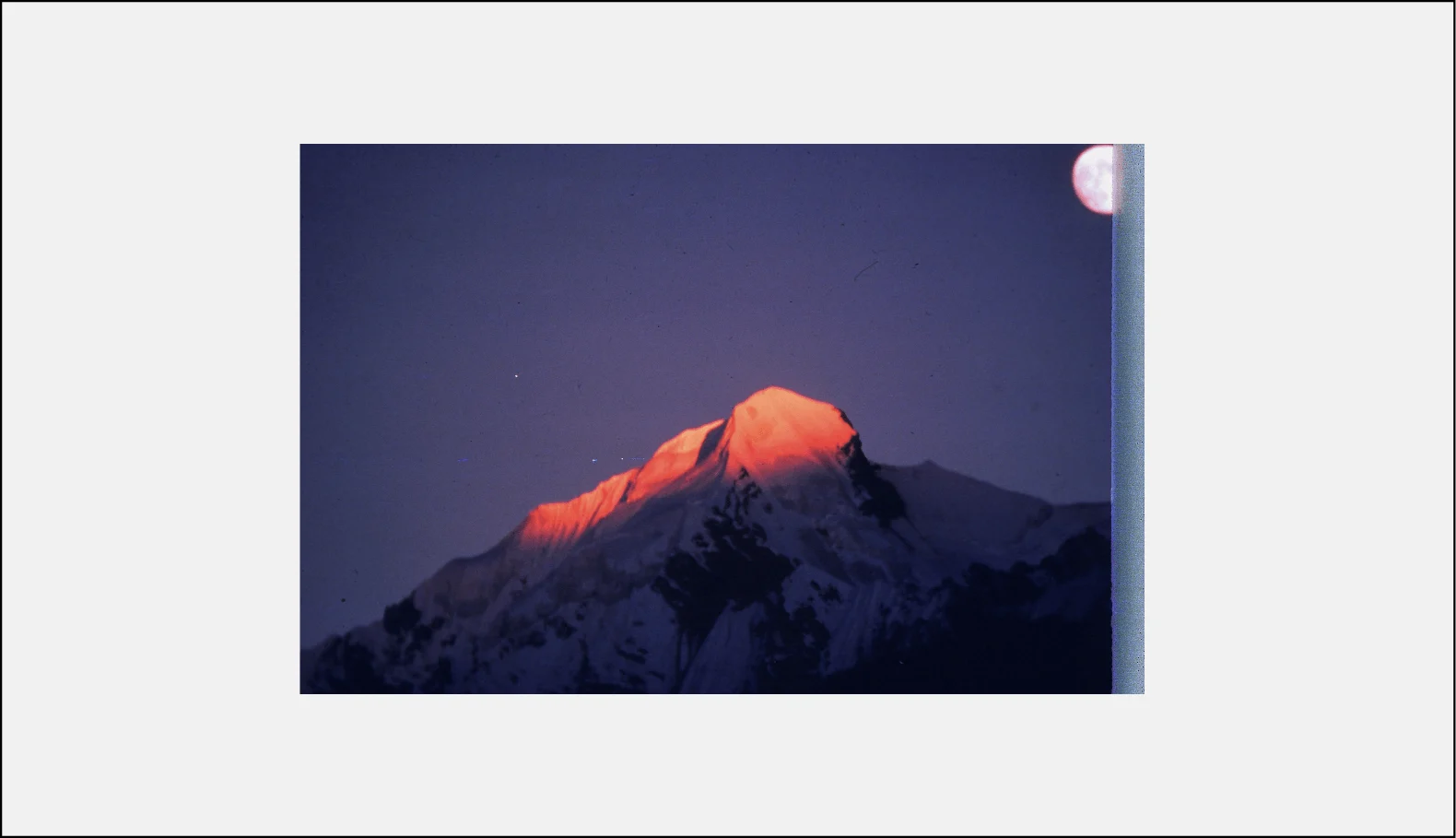

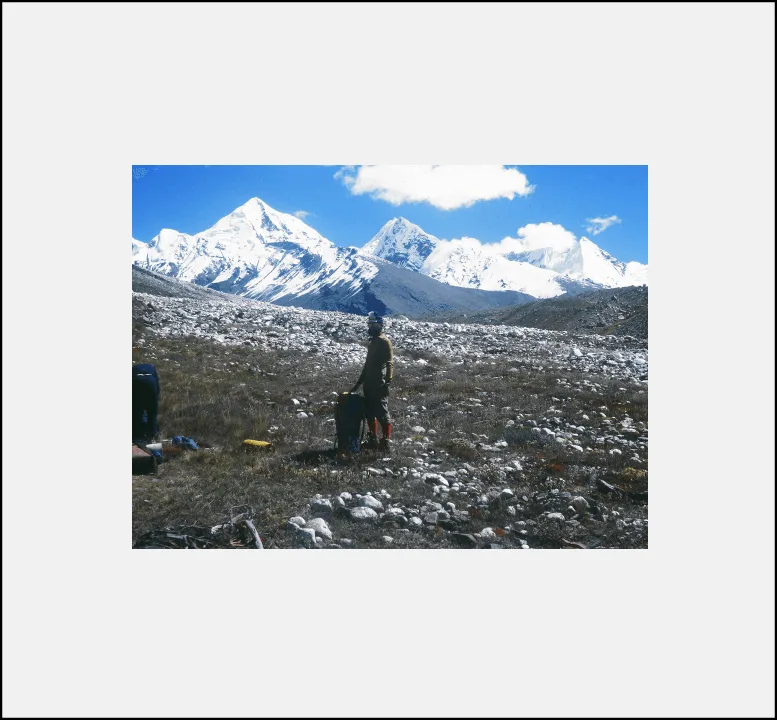

During the height of the Cold War in 1965, the CIA collaborated with the Indian Intelligence Bureau to plant a nuclear-powered surveillance device to intercept radio signals from the Chinese nuclear missile testing in Lop Nur. The chosen location was Nanda Devi, the second highest mountain in India, and one which Himali Singh Soin grew up looking at from her home in the Himalayas. After the install expedition was abandoned because of a blizzard, the device (powered by 1900 grams of plutonium) was left to become part of the landscape. It has never been found. In 1978, Himali’s mountaineer father was part of a rare expedition which took photographs of the mountain, one of which was made into a postage stamp by the Indian Telegraph services.

“This spy story is still pretty covert, especially in the current regime,” Himali explains. India’s prime minister Narendra Modi acknowledged the incident in 2018 in relation to potential contamination of the nearby Ganga river, but concrete details remain scarce, despite recent fears that radiation has contributed to local flash flooding. Himali has used this uncertainty as a springboard for static range, a speculative multi-disciplinary project for Back to Earth. Himali channels her artistic interests through a variety of imagined scenarios, both local to Nanda Devi and further afield. The 1978 photographs are still some of the only visual clues available, and suggest a complex afterlife. “If there was a nuclear leak, then there would be radiation in the (camera) film and in my father’s body,” Himali explains. “And as I wasn’t born yet, potentially in my body.”

static range continues Himali’s fascination with ice, mountains and the poles as territorial canvases for her work. Five years spent researching the Arctic and Antarctica culminated in a residency on a Tallship to 80 degrees north in 2017, from which Himali “started telling stories from the perspective of ice, an archive whose data were being lost as it melts.” The result was we are opposite like that (2019), which included a film exploring the Victorians’ anxiety of an imminent new ice age. What started as a book of poems expanded to become an almanac of astrological readings, expedition notes, weather forecasts, recipes and manifestos, combining both historical fiction and futuristic forecasts.

“I finished that project and thought: ‘what is my third pole?’” Himali says. Many links with 19th Century British colonialism emerged from her research.

“I realised that this was a really colonised space,” Himali explains. She became lured back not just to the post-imperial country of her birth, but towards her namesake – the vast mountain range at the edge of India, the empire, and the highest reaches of the earth.

If there was a nuclear leak, then there would be radiation in the [camera] film and in my father’s body.

static range comprises a series of “transmissions,” including an animation of an imaginary of the Nanda Devi stamp exposed to radiation; a letter from the device to the mountain (which Himali reads); a drum score; on-site healing and botanical planting initiatives; embroidery; and a live performance installation. All are designed to intersect, each an avenue for Himali’s speculations on nuclear culture, post-national identity, spiritual healing and environmentalism. “The letter is a kind of problematic relationship developed between the device and the mountain,” Himali explains. “They both coexist and care for each other, but they also have this relationship of toxicity.”

It begins with appeals to the mountain – “how does one move you. shift you, but also elicit emotion” – before referencing the Indian epic Ramayana, in which a monkey god breaks off a mountain peak after failing to retrieve herbs growing on its slopes. The device (or “the spy,” as the letter is signed-off) becomes an all-seeing eye, a protean being observing mountain activity while itself contaminating it: “a lady appears with an aluminium tumbler collecting what for her is sacred water.” The intimacy of the voice reflects the letter format, while also gesturing towards the cosmic: “my atomic lightness balanced with your tectonic stability enables us to stay floating in space.”

The letter is a kind of problematic relationship developed between the device and the mountain. They both coexist and care for each other, but they also have this relationship of toxicity.

The spy later tells the mountain that “you are the omniscient narrator. the second and third person. the base and the peak. peek into the future and i will be omnipresent too.” How does Himali view this process of writing the non-human into being? “I feel like I’m so deep in these voices that they’re no longer inanimate to me,” she says. “Geology and the natural world are not fixed, but constantly shifting, like identities. just as the mountain is pushed by tectonic plates, so a human is borne from quiet and then emerging.” Writing in English becomes a decolonial and ecological exercise. Himali often extends fragments of information beyond their truth to shape narrative. “There’s so much that’s speculative about the very process of radiation,” she says. Working with Ele Carpenter, a curator and writer on nuclear culture at Goldsmiths, University of London, Himali traced the effects of radiation on film and photography to inform the animation.

She had planned to attach the stamp onto film and pass it through airport X-ray machines to observe the effects. With the pandemic making this unviable, the animation became yet more fictive and hypnotic: cobalt blues and turquoises blur in and out of focus as the stamp leaks under exposure.

The “deep violences” and aesthetic sublime of William Turner were an inspiration. The Romantic painter’s “big suns and terrible eyes,” became a radiation-induced nuclear sublime, Himali says. “While it does adhere to the scientific aspects of what might happen to an image, the animation is imaginative and refers to the aestheticisation of nuclear violence.” The real-world tensions between Pakistan, India and China – and the rise of militarised nationalism in each – linger throughout.

David Soin Tappeser draws out these resonances in static range’s musical score, a speculative interpretation of the sounds the device captured during its lifetime. David plays Nagada (kettle) drums, the beaten copper shells and goat hide tops made by artisans in Almora, Uttarakhand.

Geology and the natural world are not fixed, but constantly shifting, like identities.

The sound is initially sparse but intensifies as Himali’s narration hastens. In the second half, rumbling murmurs and glitches intersperse the drumming, which sounds echoey in comparison. “The reason you hear so many scratches and glitches is that we assume the signal was not sophisticated enough to just pick up Chinese missile testing,” Himali explains. “The area being spied upon hosted Uighur concentration camps, so we imagined that the device picked up scratches of protest songs, which gives a conceit to listen to Uighur music and replicate these patterns in the drums.”

Creating international solidarity is one of Himali’s key aims with the project. With the Indian government increasingly turning to digital authoritarianism to censor its citizens, static range uses “transmissions, stamps, travel, radio, signals and coding as something that transcends the nation state,” she says. In this same spirit, Himali turned to Jordan Nasser, a New York-based artist of Palestinian heritage, to interpet the stamp through embroidery. He used the Panchachauli weave motif, originating in Kumaon in Uttarakhand, alongside his traditional incorporation of Arabic symbols. The letter is translated into German, Hindi, Hebrew and Arabic. “The whole thing is boomeranging into a completely different conflict zone,” Himali reflects.

static range is also concerned with secular empowerment via the project’s healing initiatives. “The place of the spiritual in India right now is a contested space, in a regime which is constantly co-opting religion and spiritual thought,” Himali explains. As in ancestors of the blue moon (2020), in which she gave voice to unheard, local deities, Himali looks beyond religious boundaries while also recovering ancient rituals.

Media anthropologist Viveka Chauhan will send long-distance healing to the mountain using a mixture of sound and poetry which, combining with the Nagada drums, will undo the toxicity of the nuclear radiation.

“We will also work with a local healer whose profession is undervalued, to act as a mediator and strengthen the energies on their way to the mountain,” Himali writes in the letter notes. Incorporating local people into the project is essential, she says, as is upholding ethical responsibilities. “It was really important to us to pay properly and to make everybody feel that this is something that’s valued,” she says. Part of the textile fee goes to village women to weave and sell images of the mountain; when Himali’s team visited the drum maker to explain their project, “it really felt like something endangered.” Her patronage towards the makers is as important as the narrative itself.

A Somatic Ritual from René Daumal’s Mount Analogue

1: When you take off on your own, leave some trace of your passage that will guide your return: one rock set on top of another, some grass pierced by a stick. But if you come to a place you cannot cross or that is dangerous, remember that the trace you have left might lead the people following you into trouble. So go back the way you came and destroy any traces you have left. This is addressed to anyone who wants to leave traces of his passage in this world. And even without wanting to, we always leave traces. Answer to your fellow men for the traces you leave behind.

2: Never stop on a crumbling slope. Even if you believe your feet are firmly planted, while you take a breath and looking at the sky the earth is gradually piling up under your feet, the gravel is slipping imperceptibly, and suddenly you are launched like a ship.

3: If you slip or have a minor spill, don’t interrupt your momentum but even as you right yourself recover the rhythm of your walk. Take note of the circumstances of your fall, but don’t allow your body to brood on the memory.

4: Keep your eyes fixed on the way to the top, but don’t forget to look at your feet. The last step depends on the first. Don’t think you have arrived just because you see the peak. Watch your feet, be certain of your next step, but don’t let this distract you from the highest goal. The first step depends on the last.

static range feels like it’s constantly evolving. The creation of a therapeutic garden means that planted trees – chosen specially by Ele Carpenter to absorb radiation – will long outlive the project, as will the lost device that initially inspired it. Next, Himali will visit Mount Meru, a Himalayan mountain and centre of the universe in Hindu mythology. It’s as if she’s determined to make an impact in the here and now, all too aware of the tectonic shifts beneath her which move mountains and redraw landscapes. “Even with five years of polar projects, I never said climate change once: it’s so obvious,” she reflects. “This is the slippery place that art can be in, that space of metaphor. The poetry is holding it all together and in that space of metaphor you can also do things, because metaphor is real.”

This is the slippery place that art can be in, that space of metaphor. The poetry is holding it all together and in that space of metaphor you can also do things, because metaphor is real.

Explore more

A

Alejandro Jodorowsky, The Holy Mountain. Film. Mexico, 1973

D

Daniel Kurjakovic, Every One Of Us Is A Radio Transmitter – Etel Adnan. ArtAsiaPacific Magazine, 2016

H

Himali Singh Soin, Ancestors of the Blue Moon. White Chapel Gallery, 2020

Himali Singh Soin, static range letter in English, German and Hindi. WeTransfer download, 2021

Himali Singh Soin, static range letter in Hebrew and Arabic. Granta, 2021

L

Lin+Lam, KW Production Series 2020: Lin+Lam. KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 12–30 December 2020.

M

Manan Kapoor, The Country Without a Post Office. Boston Review, 2019

Mangalesh Dabral, The places that are left. Cottage Reader, 2013

Mark Doman and Katia Shatoba, Tracing the path of destruction in India’s Himalayas. ABC, 2021

R

Rene Daumal, Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing. Book, Exact Change, Cambridge MA, 2019

U

University Of Arizona. Scientists Find Half-Billion-Year-Old Ancestral Mountains In The Himalaya. ScienceDaily, 2003

Groundwork is a collaboration between the Serpentine and WePresent. It explores the extensive research behind five artists’ proposals for Back To Earth, Serpentine’s multi-year project focused on instigating change in response to the climate crisis.

Groundwork will act as a series of accessible mini-encyclopaedias with all the references artists use to develop a final artwork. They will go behind-the-scenes on the research the artists have done as part of their project for Back to Earth, in a bid to reveal their processes and inform how the viewer might see the project as a whole when completed. It will involve diving deep into the research of artists such as Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Vivienne Westwood, Karrabing Film Collective, Himali Singh Soin and Tabita Rezaire.

Himali Singh Soin has chosen to highlight the secular non-profit Live to Love. The grassroots movement empowers communities to serve as guardians of the Himalayas and its people, with the goal to create sustainable solutions for the future of each region, and foster a culture of empowerment and of resiliency. In 2021, WeTransfer doubled all donations made to support their cause.

Cast of collaborators: David Soin Tappeser (music), Mandip Singh Soin (imagery and gardening), Jordan Nasser (textile), Ele Carpenter (nuclear culture advice), Jahnavi Phalkey (nuclear anthropology advice), Rachel Harris (ethnomusicology advice), Viveka Chauhan (healer), Anita Singh Soin (skill sharing with women weavers), Sudama Lal Tamta (drum maker), Suresh Bisht (on-site coordinator), Tiziana Mangiaratti (animation assistance), MJ Harding (recording).

Back to Earth is curated and produced by Rebecca Lewin, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Jo Paton, Lucia Pietroiusti, Holly Shuttleworth and Kostas Stasinopoulos. static range was made with the support of Serpentine, Prince Claus Fund, EWERK, HKW and WePresent.