Writer Shonagh Marshall meets Peruvian photographer Prin Rodriguez to unpack the layers of meaning behind her photo series Katatay and find out why there’s magic in myth.

Photographer Prin Rodriguez grew up in a town called Pativilca in central Peru. “When I was a child, my family didn't have a camera of our own so for special occasions we would borrow one, or my parents would call the town photographer,” she remembers. “The photographs we had were scarce and very valuable. I remember taking out the albums to look through them, imagining what the moments captured in the photos had been like. I would consider the passage of time, how the people and spaces had changed. I think in a subtle way this framed the intimate relationship I feel exists between photography and dreaming.”

It is the way we craft images as relics of the past that Prin ruminates on in her work. Taking the book From Gods and Men of Huarochirí as the starting point for her last project Sons of Pariacaca, she constructed a contemporary imagining of the native Inca culture Quecha. “When I finished studying photography, my boyfriend and I decided to move to Cusco a city in southeastern Peru. Before moving, I was photographing groups of modern and contemporary dance in Lima” she explains. “In Cusco I began to photograph folklore groups, but as time passed I became increasingly confused around the complexity I felt for these ancient rituals. On one hand I had a great amount of respect for the early folkloric traditions and on the other I was intrigued by the contemporary view of folklore.”

The text From Gods and Men of Huarochirí captures the stories of the Inca population, who were all but wiped out when the Spanish colonized Peru in 1533 and brought diseases that killed 90% of the native people. As a document the book is an important relic of this indigenous culture. Prin began to consider how her images might be able to capture something of the essence of the book through visual form, imagining this culture from a contemporary viewpoint. “From Gods and Men of Huarochirí of is one of the most important texts on the Andean worldview compiled from the Quechua oral tradition. It transmitted to me a poetic and powerful vision of the past that transcended time, a fluid and crystalline vision that emanated beauty,” she says. “I did not approach the text in an anthropological way, but in a sensory way. I remembered how my grandparents told the ancient stories of their lands, this vision of power and the beauty that radiated through the Apu Pariacaca. Then merging this with the questions that were echoing in me about the world I lived in became the starting point for Sons of Pariacaca.”

My connection with myth is emotional.

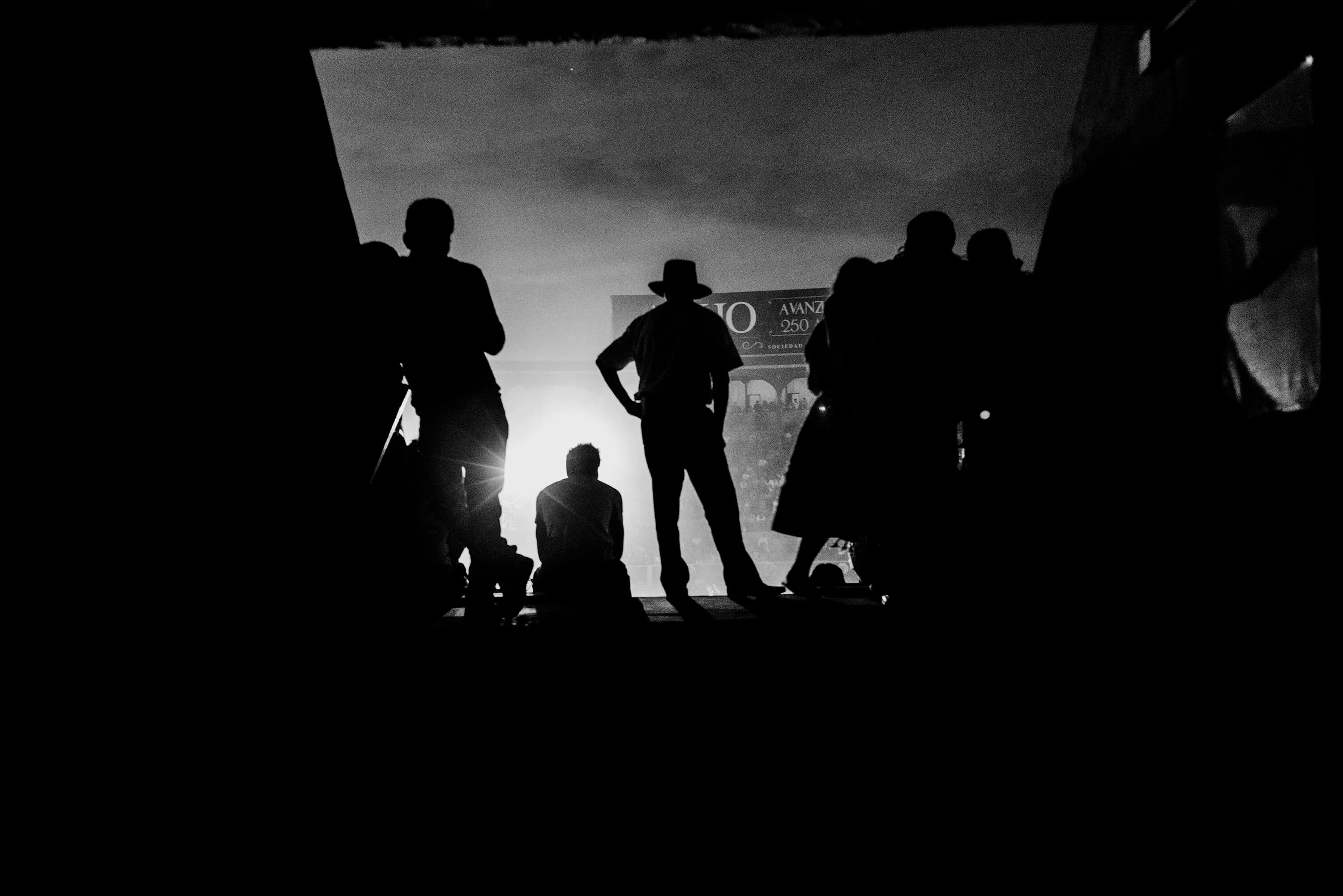

The resulting work approaches ideas of identity, and in the wake of many migrating from rural areas to big cities it raises questions around how the younger generation marries their cultural heritage with their future. In her most recent work she continues to delve into this fertile space. Called Katatay, it is named after the poem by José María Arguedas, meaning trembling in the Quecha language. In the images Prin documents the Vencedores de Ayacucho, a carnival held in Lima where participating groups perform, each representing the provinces that make up the city of Ayacucho, the site of the battle in 1824 that secured independence for Peru from the Spanish. At the carnival each troupe presents to music. Dynamic and enthralling, they perform in traditional attire. Once finished the arena of the Plaza de Acho opens as a dance floor for the attendees and the night’s festivities close with the announcement of the winning group. A quechua and mestizo tradidion, the carnival is organised to acknowledge the many families that migrated from Ayacucho to Lima in the 20th Century.

“Through the body of work I am looking to understand who I am and where I came from,” says Prin of the series that was taken between 2015 and 2018. “I was raised in the city but I too have links to the countryside through my family and my travels. I believe in Peruvian culture, the rural landscape and the city are always intertwined, not only through ancestral stories, music, dance and images; but also socially and politically. There are boundaries that have been built throughout history, and still survive, but I think to truly understand this territory you have to recognize the tension.”

The photographs that make up Katatay are longing and pensive, all black and white, the splendor of color can only be imagined. By stripping this away the body of work becomes steeped in drama. In the capture of dust plumes from beneath the dancers feet, the silhouette outlining an audience member, and the exhausted performer collapsed on the ground, you see image after image play out in a poetic patter—evoking a quiet proximity. “At the beginning I spent time photographing the arena, where the troupes dance, but as time went on I began to capture the transition and preparation spaces and portraits of the audience too. I decided the images should be black and white to capture the impact I felt that existed between the light and shadow, in some cases taking them more towards the shadows to increase the explosion of the light I felt they held.”

The world Prin Rodriguez creates holds so much of the magic and myth of her ancient Peruvian culture. “My connection with myth is emotional. For me myths show the human search for answers, dissolving borders between reality and fiction, they take us to a transcendental terrain and open up diverse interpretations.” This is exactly what these images do—in their very creation they join the vestiges and fragments that help form and construct myth.