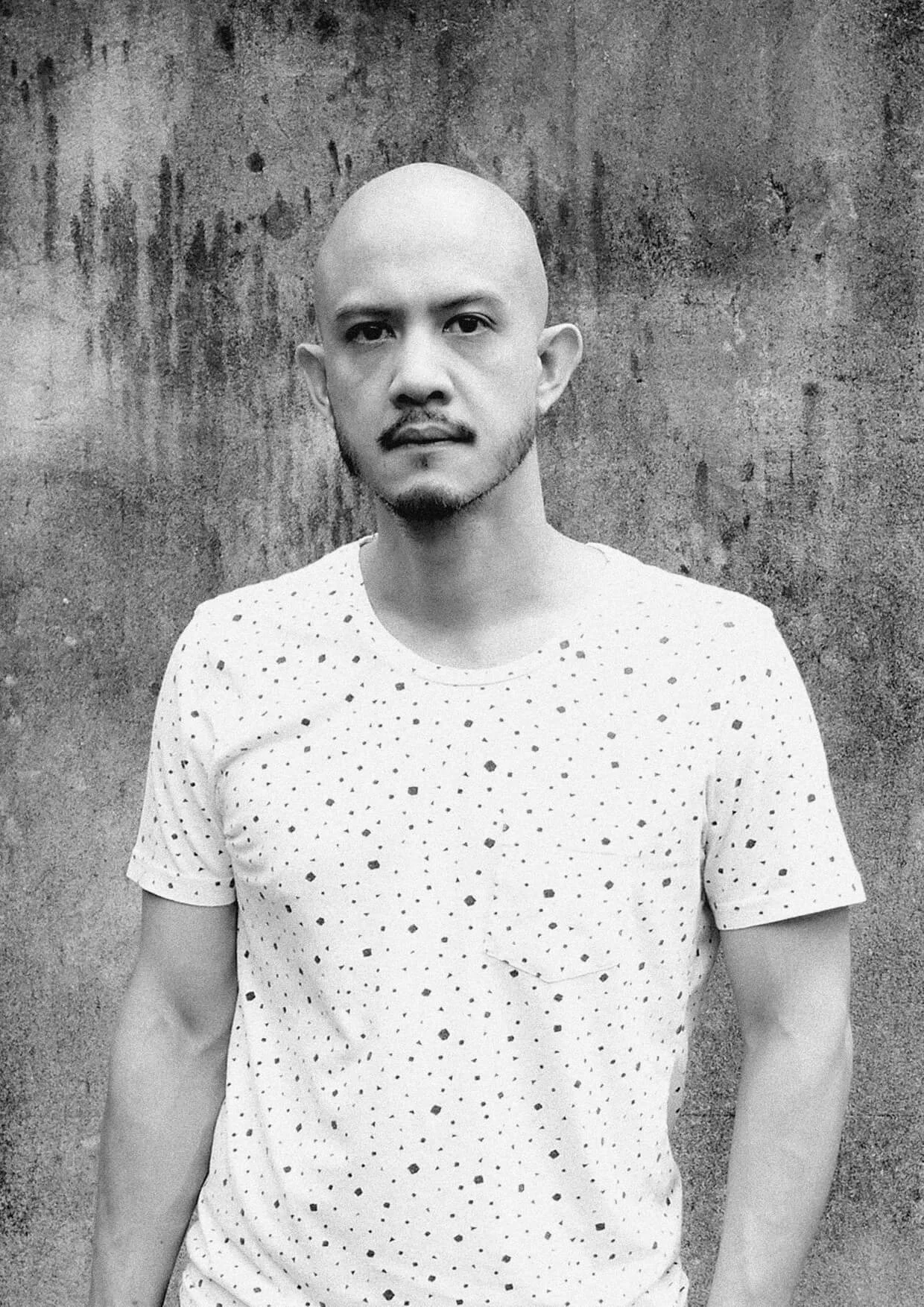

Prabda Yoon is a multi-talented creative mind who moves between writing, design and filmmaking. But he works against a tense political and cultural backdrop in his native Thailand, where art and artists come under great scrutiny. Jaime Wolf went to Bangkok to meet him.

Cover illustration by Jacco Bunt

Listen: Prabda Yoon has come unstuck in time. An acclaimed Thai author, translator, filmmaker, graphic designer, illustrator and occasional indie pop musician, Prabda has been reliving his past at the same time he maps his future.

A leading figure on the literary scene, his fragmentary, whimsical and unsettling fiction is credited with bringing postmodernism to Thai fiction. Prabda experienced early and unexpected success when his second book of short stories, Probability, published in 2000 when he was 27, won the prestigious S.E.A. Write Award two years later.

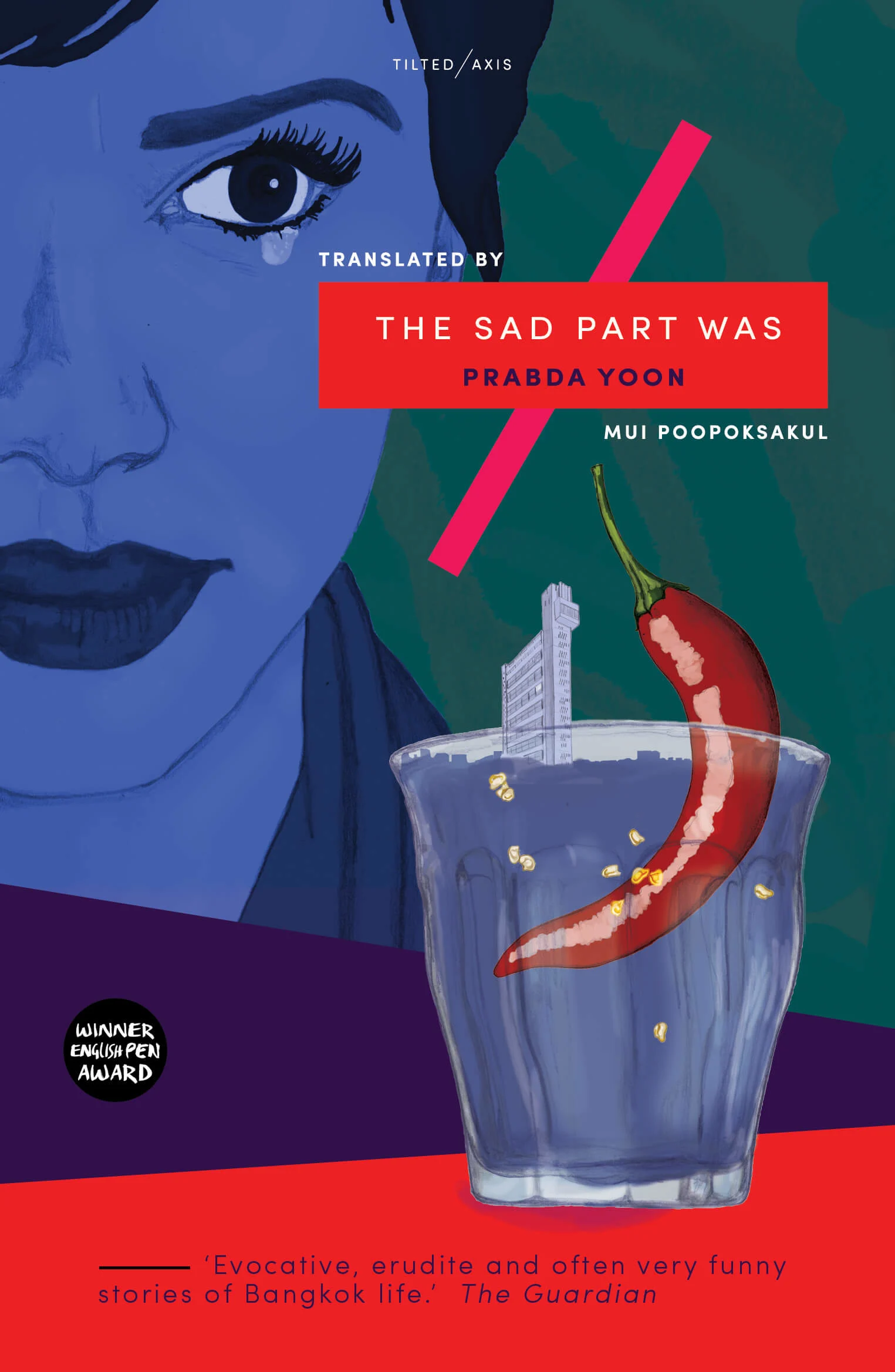

While he’s produced a steady and evolving body of work across different media over the years since, his early stories have only lately been published in English, thanks to the adventurous UK publisher Tilted Axis Press. The Sad Part Was, published in 2016, and Moving Parts, which came out in the fall of 2018, are the first translations of Thai fiction to appear in the UK.

As his English translator, Mui Poopaksakul puts it, Prabda’s stories are marked by “circular structures, cryptic endings, tons of wordplay.” Where “authentic” Thai literature had been associated with social realism and rural settings, Prabda’s urban mood-pieces introduced a new cosmopolitanism to the field, their drifting, melancholy young protagonists infused with an international-millennial late 1990s sensibility.

I would be standing on stage among the musicians, not doing anything

As a young star in Thailand, Prabda enjoyed the kind of shallow celebrity that such accolades confer: appearing on magazine covers, dating actresses, writing screenplays for new wave film directors. Enamoured of post-punk music by The Cure, The Smiths, New Order, Nine Inch Nails and The Pixies, he told the publisher of his debut novel, Chit-Tak! that it should have a soundtrack. This led to Bua Hima, one of the country’s leading indie bands, recording a set of songs with his lyrics.

“It was a weird time,” Prabda remembers. “Universal Music decided to distribute the soundtrack and some of the songs became quite popular. I was invited to go on television with the band, but since I had only written the lyrics and another guy sang, I would be standing on stage among the musicians, not doing anything!

“My first book, Right-angled City, was a collection of stories that all took place in New York City, so in the Thai media, I became an expert on New York. If anything happened there, I would be called to comment.”

Little of this renown reached beyond Thailand or Japan (where he became a popular magazine columnist). And over the years, Prabda has done his best to disengage from celebrity culture while going on to publish 20 more books, including a non-fiction account of the 2004 tsunami commissioned by the Thai Ministry of Culture.

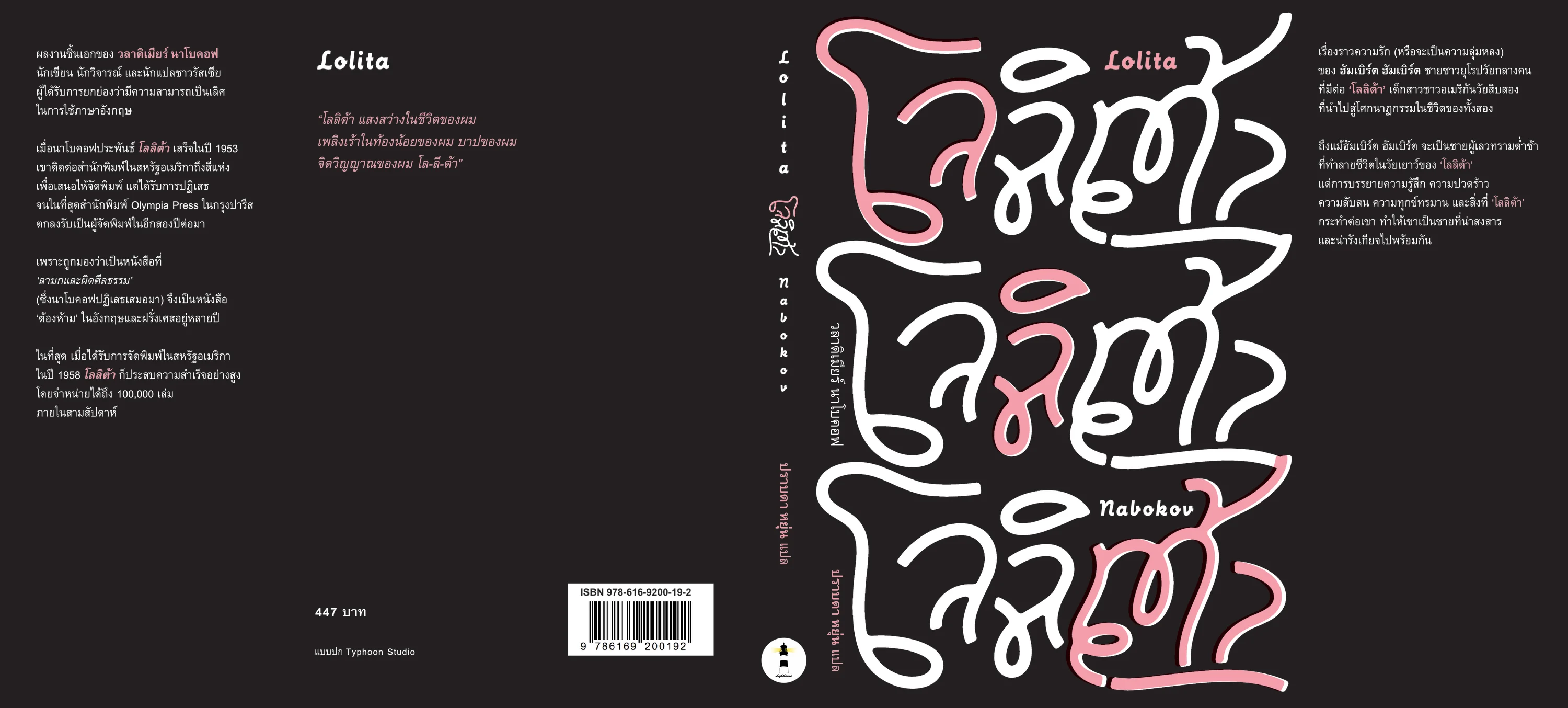

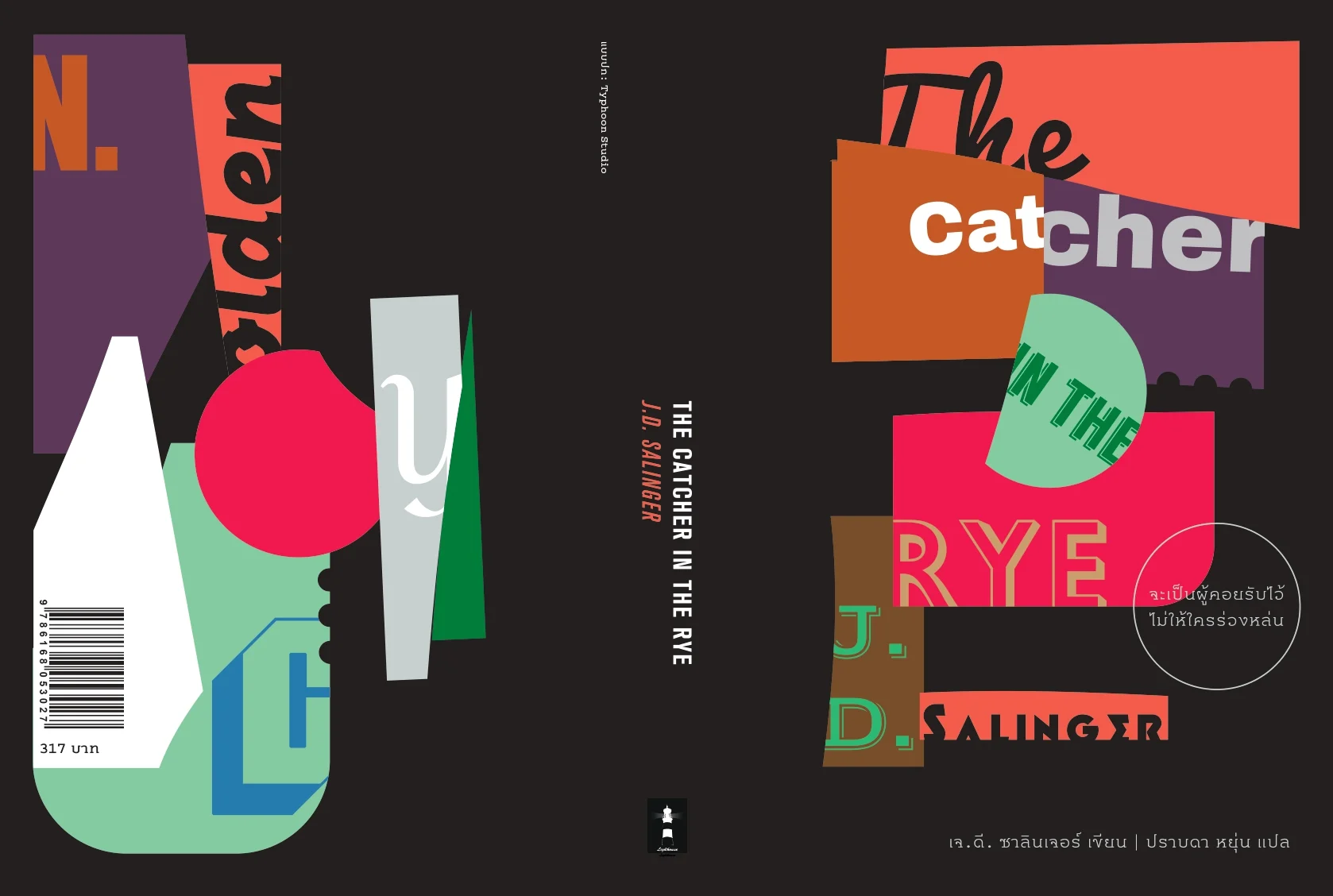

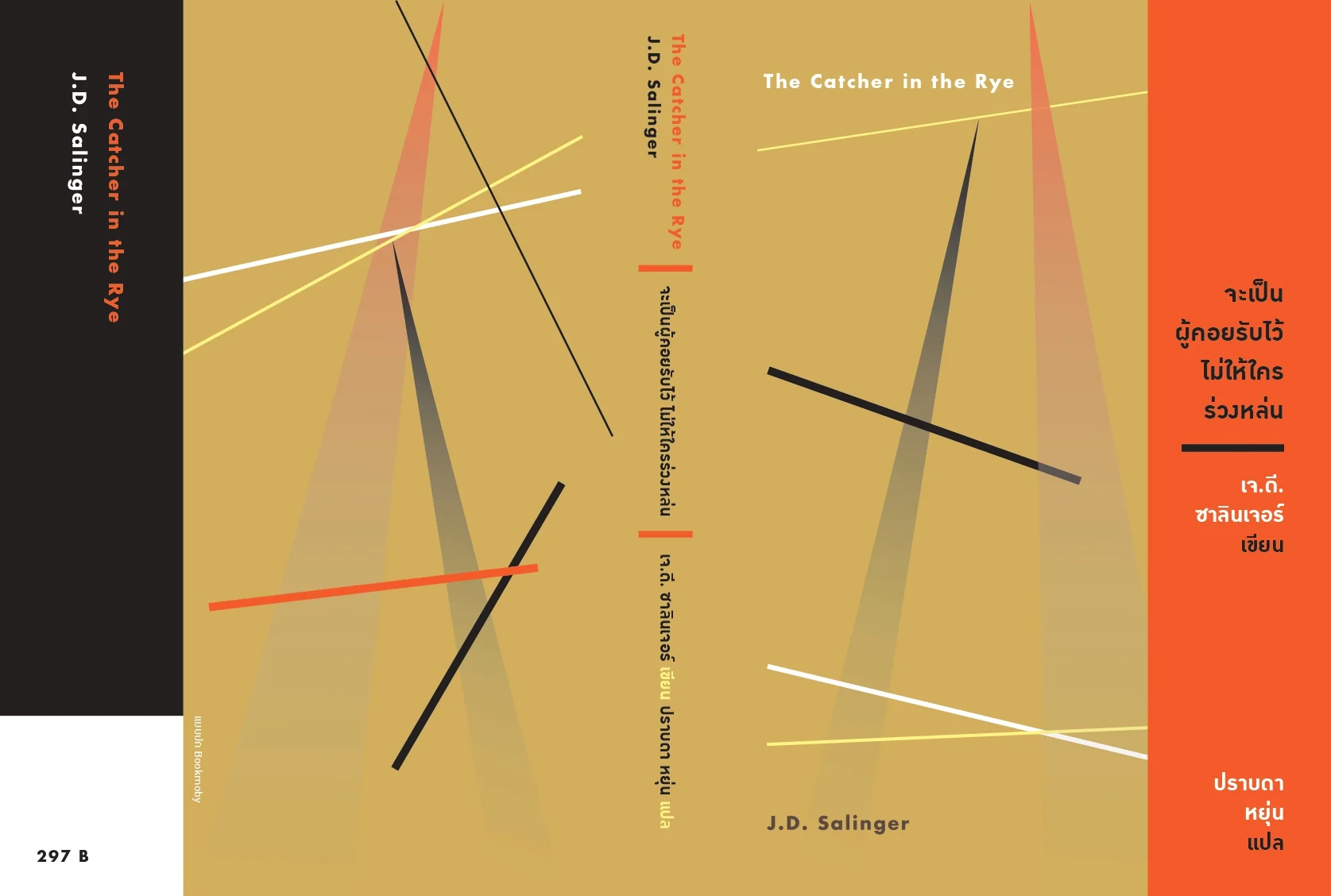

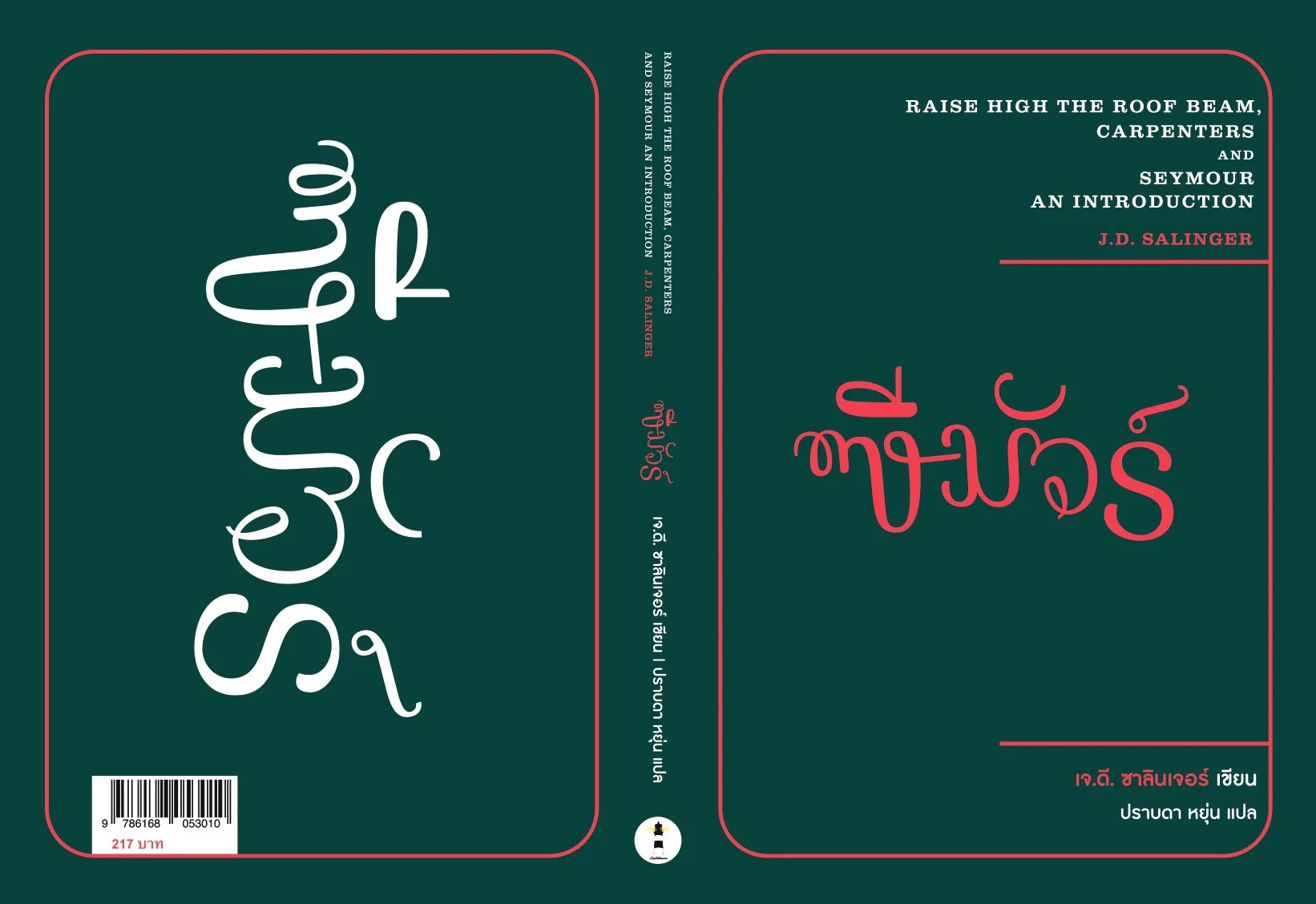

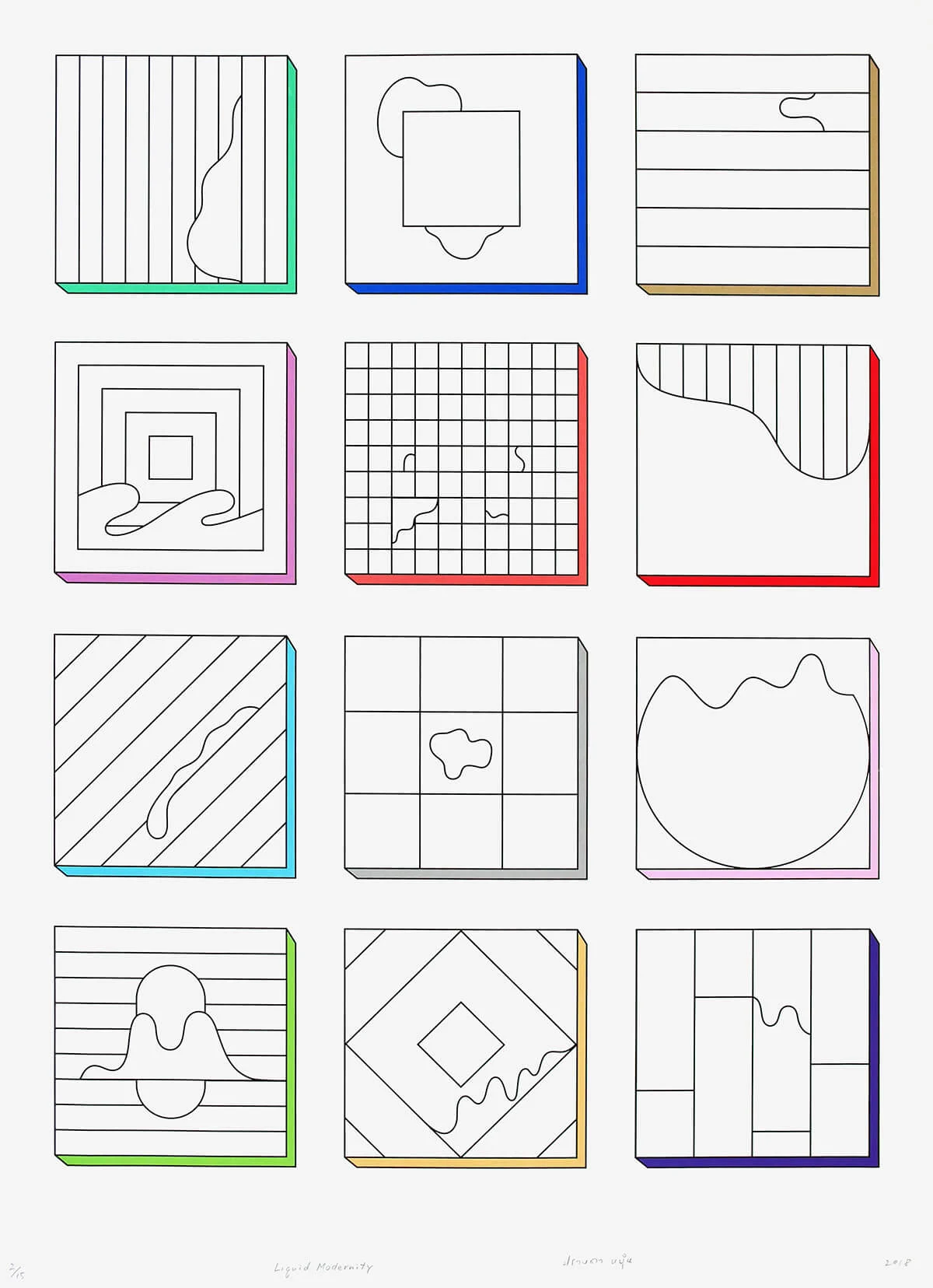

He started an independent publishing house, Typhoon Books, which publishes some six titles a year in addition to his own work, in distinctive editions that Prabda designs himself. He has translated JD Salinger, Vladimir Nabokov, Anthony Burgess, Karel Capek, and Arthur Bradford into Thai. And since 2016, he has written and directed two feature films, as well as a short film commissioned last year by Columbia University’s Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

The often-quoted line, “It’s a sad and beautiful world” from the Jim Jarmusch film, Down by Law seems foundational to Prabda’s worldview. It’s echoed near the end of Last Life in the Universe, a comic-fatalist film he wrote in the early 2000s with the director Pen-ek Ratanaruang.

In one scene, as Japanese superstar Asano Tadanobu and the Thai actress Daran Boonyasak are driving along a tropical highway, Boonyasak sighs, “This is beautiful.”

“Are you sad?” Asano asks.

“Everybody’s sad,” Boonyasak replies.

To be honest, it’s so long ago, it can be hard to feel connected to the person who wrote those things

Now in his mid 40s, Prabda has enjoyed a mature career during decades that have seen Thailand increasingly troubled by social and political turmoil, a violent separatist movement in the country’s south, and the installation of a military government that has tightened censorship, rewritten the constitution, and driven the country steadily away from its 20th Century democratic roots.

To navigate such shoals – steered by a sense of artistic responsibility to improve conditions at home, while figuring out what can and cannot be said – has necessitated some changes in Prabda’s style and approach.

At the same time, Tilted Axis’s translations have led to the publication in Italy, China, and (soon) Portugal of The Sad Part Was, and he is experiencing what might be an all-too-appropriately Prabda-esque sense of bemused cognitive dissonance at his newcomer status via the revival of his early work.

“I have a hard time sometimes talking about it,” he says. “To be honest, it’s so long ago, it can be hard to feel connected to the person who wrote those things.”

Wordplay and whimsy, he says, have become less pronounced in his writing over the years – his goal has been to simplify and pare down his prose, while Thai society and politics make quirkiness seem an increasingly inadequate response.

Prabda continues to approach things from an oblique angle, his fiction still contains robots and ghosts, takes place in the future, and features surrealistic and magical turns of plot (the novel he published last year, Basement Moon is set in 2069 and narrated by an advanced artificial intelligence program).

But at the same time, it’s easy to read his 2018 film, Someone from Nowhere, in which a stranger shows up at a woman’s apartment claiming that it belongs to him, and engages her in a high-stakes debate about ownership, memory, and identity as a political allegory, while the recent short film, Transmissions of Unwanted Pasts concerns a satellite that is able to see events from the past that have been hidden from the Thai people.

Prabda claims he only became a writer by accident, although it may have been inevitable. His father was the founding editor of the The Nation, an English-language newspaper; his mother was an editor at a fashion magazine, and their book-filled home was a gathering place for writers and intellectuals.

His first loves were translated editions of Sherlock Holmes stories and Chinese martial arts novels, but Thai literature left its mark as well – among early influences, Prabda cites Kukrit Panoj’s 1954 novel, Red Bamboo, the Thai monk Buddhadasa’s writings on Zen, and a pseudonymous author who called himself Humorist. “He was a Thai language teacher, and he would criticize the use of the Thai language in the media,” Prada explains. “It was satirical: political, but not in an aggressive way.

He went to high school in the US and was drawn to visual art, which he subsequently pursued at Parsons School of Design in New York. He was working as a graphic designer when he came home to Thailand in 1997 for compulsory military service.

“In 1998, I had been back in Bangkok for a year,” he explains. “I started to write short stories just to see how my Thai was. I sent them to magazines and they published them. Things happened so fast – two years later, I won the SEA award. I became a writer in that way. It wasn’t really intentional.”

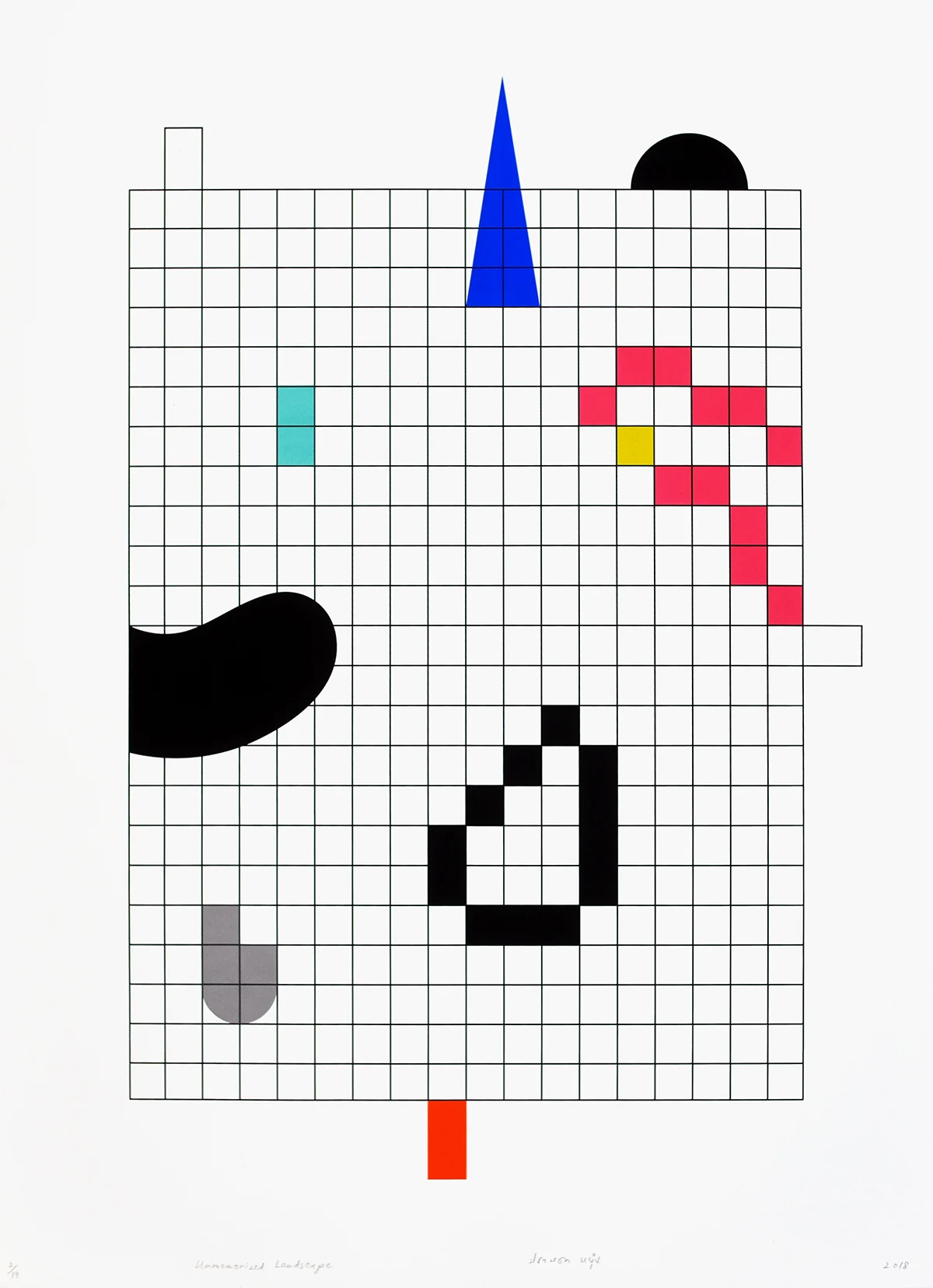

Asked about the overlap between his career in visual art and filmmaking, and his writing, he declares them separate and unrelated. But at a recent workshop for young Thai writers, he made an important connection between these two sides of his creative practice. “I write as if I’m drawing, with no clear plan,” he said. “I tried outlining, but it didn’t work for me. When I sit down to write, I follow wherever the line takes me.”

Picking up the thread in a later conversation, he explains, “I started writing stories when I was 12, but I never really thought I’d become a writer. As a teenager, I would pick up a Don Delillo paperback because the cover was by Andy Warhol.

I tried outlining, but it didn’t work for me. When I sit down to write, I follow wherever the line takes me

“My high school in the US was a progressive school with a huge art department, and right away, with my broken English I was asked to design a set for a play. They had all the foundation classes – still-life drawing, photography, Super-8 filmmaking. After that, I studied with Milton Glaser at the Cooper Union. I always thought I’d be some kind of visual artist: a creative director or graphic designer and I was – I worked at a small firm.”

Prabda traces his interest in film to his mother, who let him watch the European arthouse films she rented on VHS. “I really loved Fellini’s 8-1/2,” he laughs. “I saw it when I was about 10.”

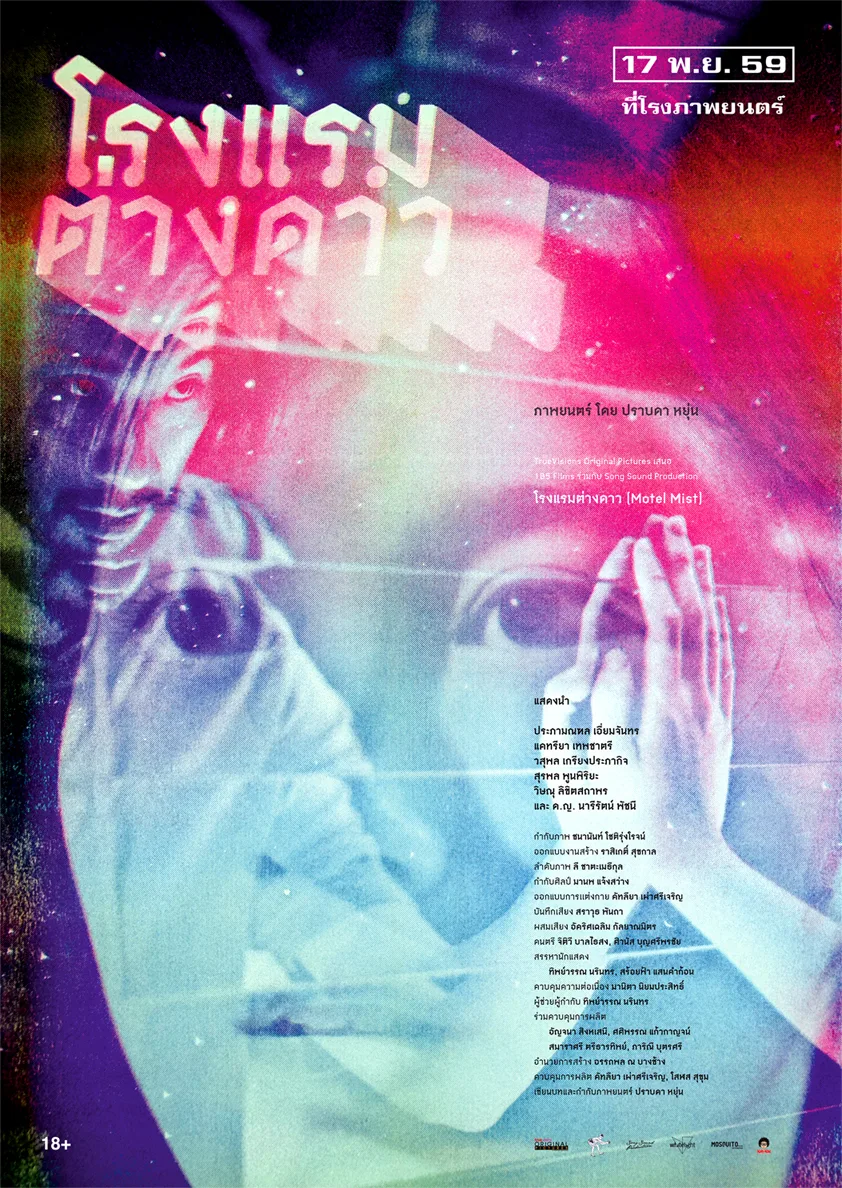

In the late 1990s he started writing a weekly film column about old movies he rented. The movie director Pen-ek Ratanaruang was a fan and this led to Prabda writing Last Life in the Universe and Invisible Waves with him. Prabda’s own move into directing, with Motel Mist, came about in an unusual way. “A director asked if he could adapt one of my novels, and I felt like I didn’t want that,” he explains. “I asked, ‘Why can’t I just write something new?’ So I wrote the script, and then the director dropped out, and I wound up directing it myself.”

Taking visual inspiration for the film’s lighting and atmosphere from Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, Prabda brought his own stylistic touches too. “I’m really interested in the passing of time. I want to show the things that get cut out of most films. Awkward silences between people are more interesting to me. I don’t get bored.”

Motel Mist was actually pulled by its producers who felt uncomfortable about its sexual themes and the reaction the movie might provoke in Thailand. To appease them, Prabda agreed to make another film on a small budget, and that became the fierce drama, Someone From Nowhere.

In the midst of surveying his broad range of work, Prabda stops. “The question I can’t really answer right now,” he says, “is if I were young and coming up today, what would I do? I can’t say if I would write fiction, or try to make films, given the changes in technology and consumption. What to do next remains an open question.”

The thread that ties his work together, he believes is innovation. “Experimentation is one of the most important things. I don’t want to do the same thing over and over again. My interests in cinema and literature come from different places, they feel like different worlds.

“I appreciate cinema for its ability to create something visual and silent. With literature it’s almost the opposite – the fun thing is wordplay and the formal structure of the language.”

At lunch on the day of the creative writing workshop, the Assistant Cultural Attaché from the US Embassy asked Prabda if his writing had changed as a result of Thai politics, and he said “I don’t consider myself a political writer. I don’t wake up in the morning wanting to make a point, but it’s very polarized now.

“When I started, my concerns were more universal,” he continued, “but a lot of my later work has become more philosophical in terms of social issues, more specific.

“The more I lived here, the more difficult it was to ignore the problems around me. At the same time, I’m very aware of what can and cannot be said – writers here are less subject to overt censorship, but we all self-censor. People here need to be free to discuss the issues. Now when they do, they fear someone will come knocking on their door.”