Nikita Vasilevskiy grew up in the North-Western Russian city of Murmansk, becoming used to long, cold winters and short, far-from-hot summers. When he visited the North Pole with his dad in 2010, the climate was not much of a shock to him, but the experience definitely was. He recreated every moment in The Diary of Barneo, from the day the ice beneath them cracked, to the chocolate bars he enjoyed, and he still looks at the diary to remind him of fond memories. He tells Alex Kahl about the parts of the trip that stand out the most in his head, and why keeping a visual diary is so important for him.

When Russian illustrator Nikita Vasilevskiy’s dad invited him to join him on a complex, high-altitude expedition to the Barneo Camp in the North Pole, he wasn’t too keen at first. His dad is a professional marine photographer, and the trip was annually organized by the Expedition Center of the Russian Geographical Society. “Do you think I wanted to go?” he asks. “Not at all! Our family lived beyond the Arctic Circle in the city of Murmansk for 15 years, and I was sure that I had nothing more to do in the North.”

Having reluctantly agreed to it, Nikita decided to pack his notebook and a pen, to keep a diary of his trip. Funnily enough, his commitment to keeping a graphic journal of his life was inspired by his love for the film Back To The Future. After watching it as kids, he and his brother were inspired by the idea of remembering the past and looking to the future, and agreed to keep graphic diaries as a way to preserve their memories for their future selves.

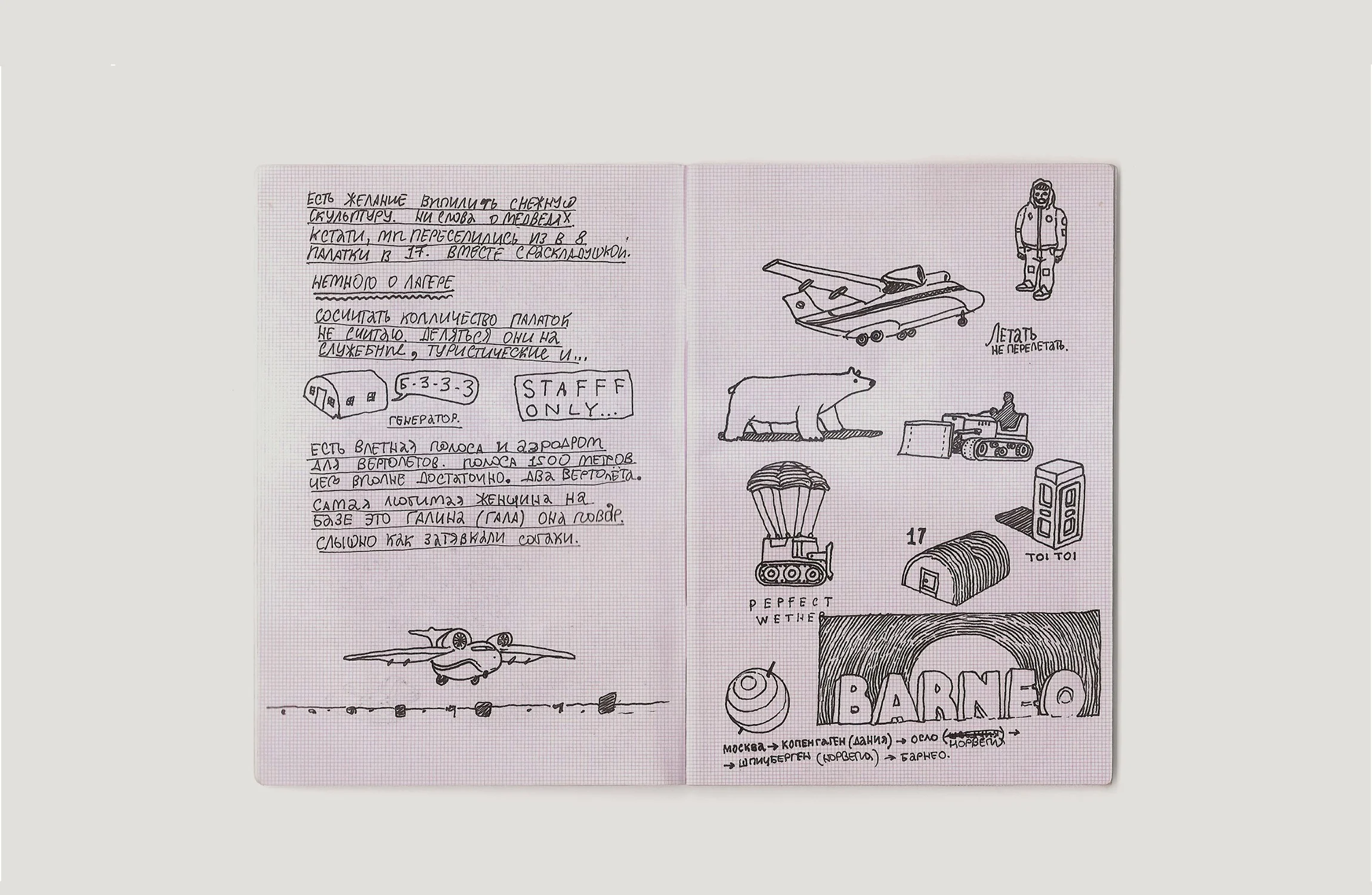

A few hours after taking off from the city of Longyearbyen located on the island of Svalbard, the plane gently touched down on the ice at the camp of Barneo. The first thing Nikita saw was a sign showing the distances to capital cities around the world. “Then someone told me that these are not exact values, because the ice drifts and every day the camp occupies new geographical coordinates,” he says. They sat down for lunch and ate soup in the main tent, and Nikita was soon taking short notes about the camp: “The cook’s name is Galina. The ice runway is 1,500 meters long. We were placed in tent number 17.”

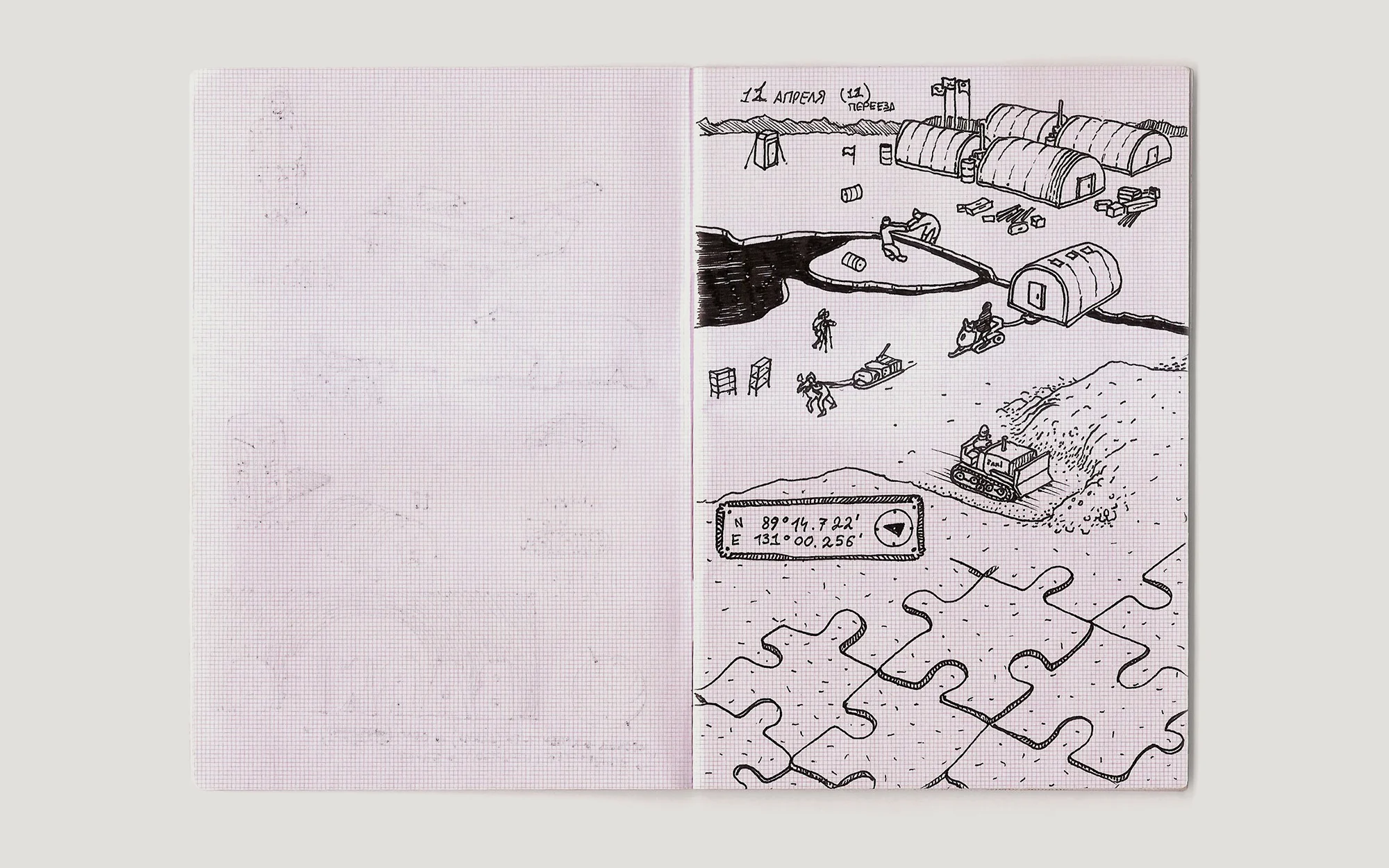

Things didn’t stay so calm and comfortable for long, though. His dad frantically woke him up early the next morning, and he looked to see a huge black crack of open water widening less than a metre from the tent. “This is the most vivid memory I have from the camp. Before the trip, I asked my father if the ice could crack. He said no, son, the ice is too thick,” Nikita recalls. He drew the scene in his diary, depicting explorers quickly dragging barrels of oil and other supplies across the growing crack, desperately clearing snow and looking for a safe place to set up a new camp. Incredibly, they didn’t lose a single piece of equipment.

In the corner of the scene, Nikita drew little puzzle pieces into the snow, showing in his own playful way how he realized that day just how movable and fragile each little block of ice is. This is something he does throughout the diary, not just sketching the literal scene around him, but looking deeper, showing the way he saw things, and how he found the funny side in them.

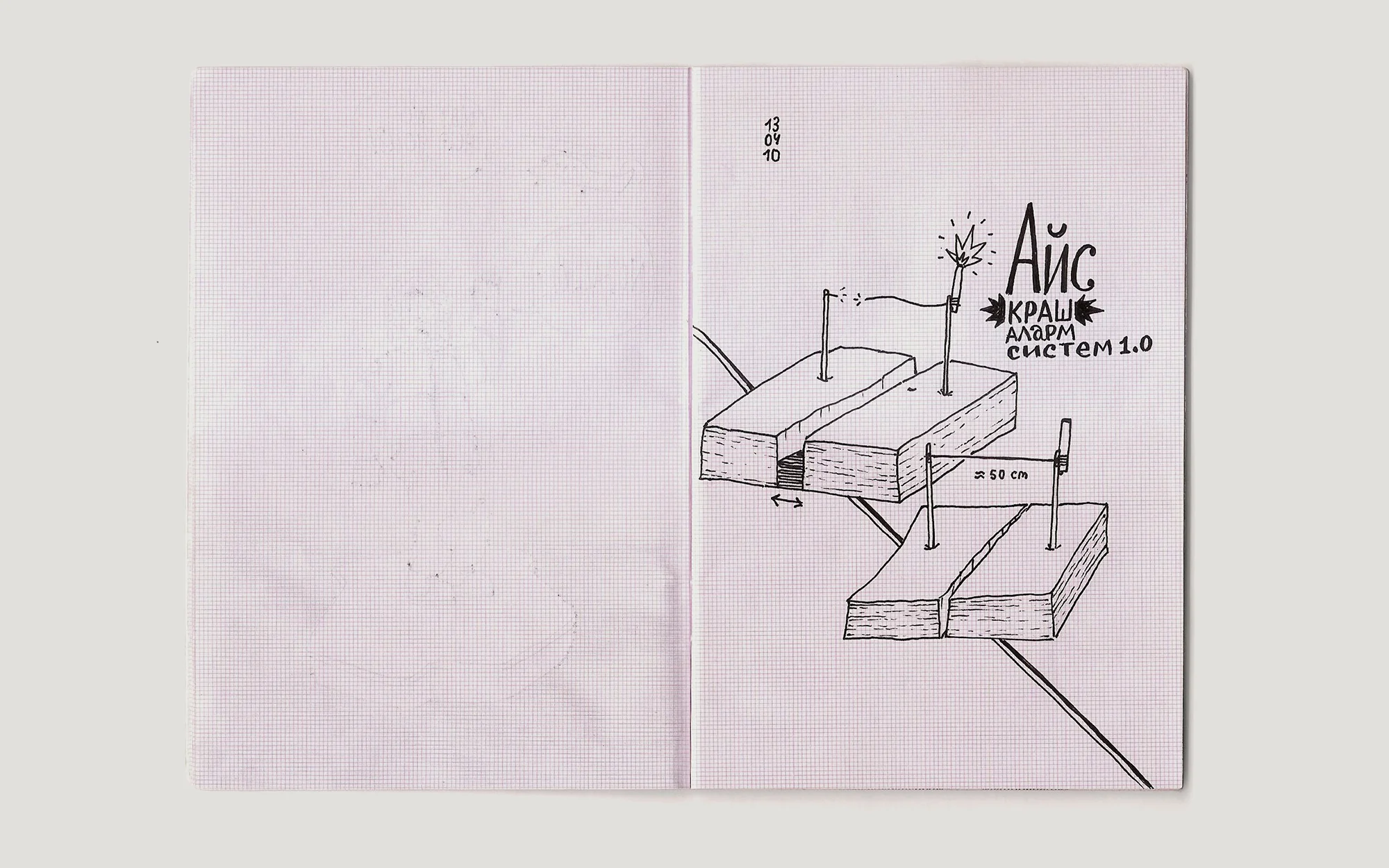

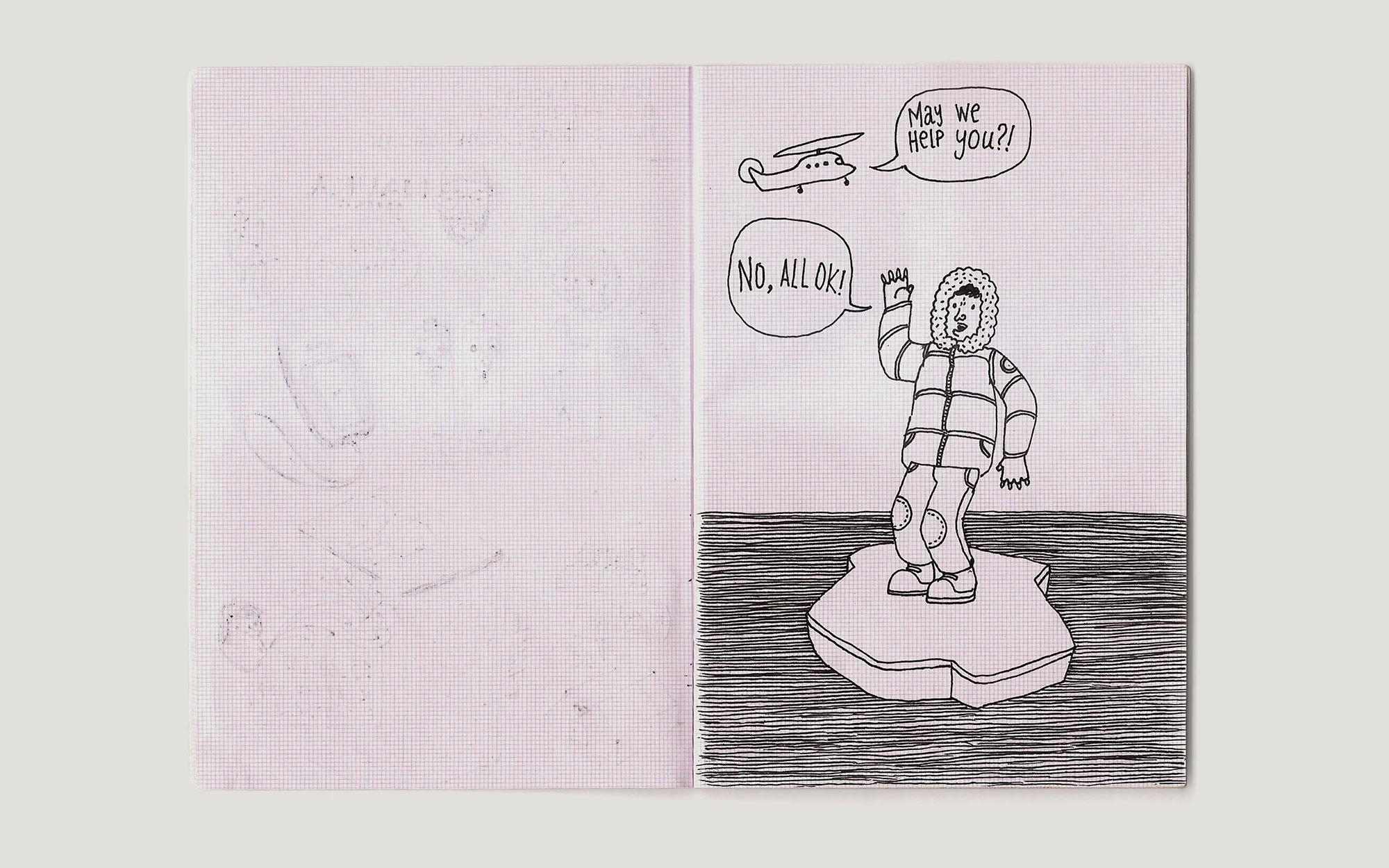

Nikita drew every tiny detail he noticed while at the camp. Chocolate bars they ate, chairs they sat on, tents they slept in. He drew the different kinds of snow boots people were wearing, and the tools the explorers were using. One diagram shows the 3 meters of ice separating his bed from the daunting 4200 meters of water below. After the ice split, he eventually saw the funny side, drawing himself floating adrift on a small shard of ice, calling to the rescue helicopter that he was doing just fine and didn’t need saving. On one page of the book he drew a plan for an invention he’d come up with to alert explorer teams when the ice was beginning to crack. A simple contraption, when the ice sheets moved away from one another, a length of string would snap and sound the alarm. “Yes, I even thought of patenting my invention,” he laughs.

“You know, in spite of the fact that we were all intact, breaking the ice was still a rare event. I got this incredible adrenaline rush. And when you’re scared, you have to try to laugh,” he says. “Apparently I'm always scared, that's why I joke a lot!”

He found himself scared again on the final day of the trip when they appeared to be stuck at the camp, as the Eyyafyadlayokyudl volcano erupted and the skies over Europe were closed. Luckily, a group of hockey fans who arrived at the camp for one day agreed to take them aboard a charter flight to Moscow.

Even though he wasn’t sure about the trip at first, Nikita looks back on it fondly. “Only a few years later I realized how cool it was that I visited the North Pole,” he says. “It was a journey with a delayed impact. For a while, I forgot I even did it and didn’t even tell my friends. Only now do I understand it was a once-in-a-lifetime trip.”

“When you’re surrounded by ice, with no internet and nothing much is happening, you start to appreciate simple things like eating chocolate and chatting with people,” he says. “People go to the camp of Barneo from all over the world. Travelers, scientists, athletes, tourists, English princes – they all eat soup under the same roof. You never know which experience will leave an impression on you for the rest of your life. So, if you are invited somewhere – go. Thank you dad!”