What effect can decades of friendship have on creative collaboration? In 2020, Marianne Faithfull teamed up with Warren Ellis and a group of their best friends and favorite co-creators to make She Walks in Beauty. It’s a record imbued with timelessness, friendship and purity, created in a time of turmoil and pain. Liv Siddall speaks to Marianne Faithfull, Warren Ellis and friends about the power love and devotion can have on the sound of music.

Illustrations by João Fazenda

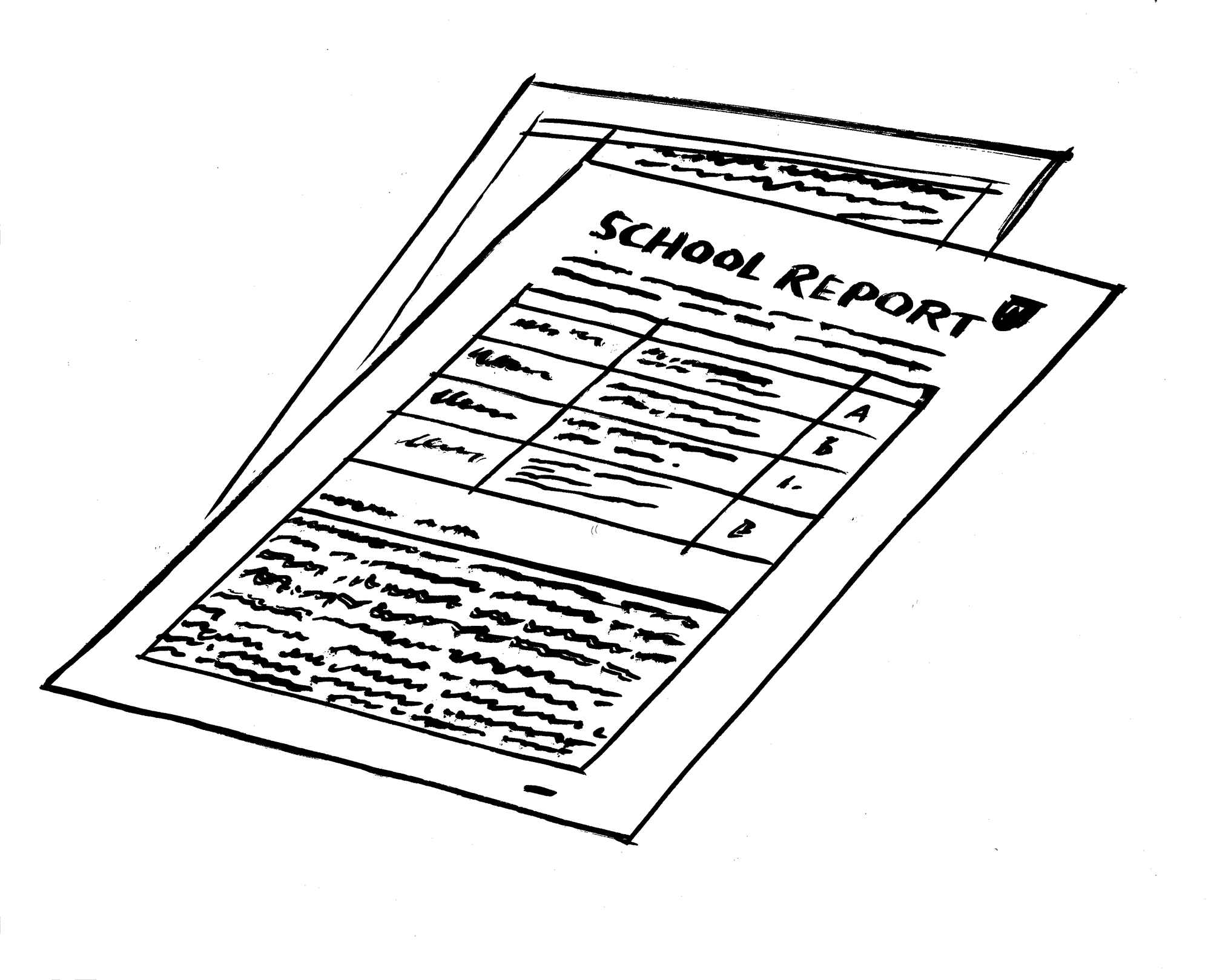

In 1964, when Marianne Faithfull was 17 years old, she received what would be her final school report. It wasn’t great. The report portrayed a careless, forgetful girl who very much could do better. The report makes more sense when you realize that it was written in the same year that Marianne was discovered at a party by the then Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and was on her way to becoming one of the world’s biggest pop stars, while simultaneously – according to Rizzoli biography A Life on Record – being deep in the thralls of a first love. No wonder she was distracted.

There was a good remark on the report, though, for English Literature. “Marianne’s interest and wide reading, added to a pleasing and mature style have resulted in good work,” her teacher commented. “I hope she will be able to continue.”

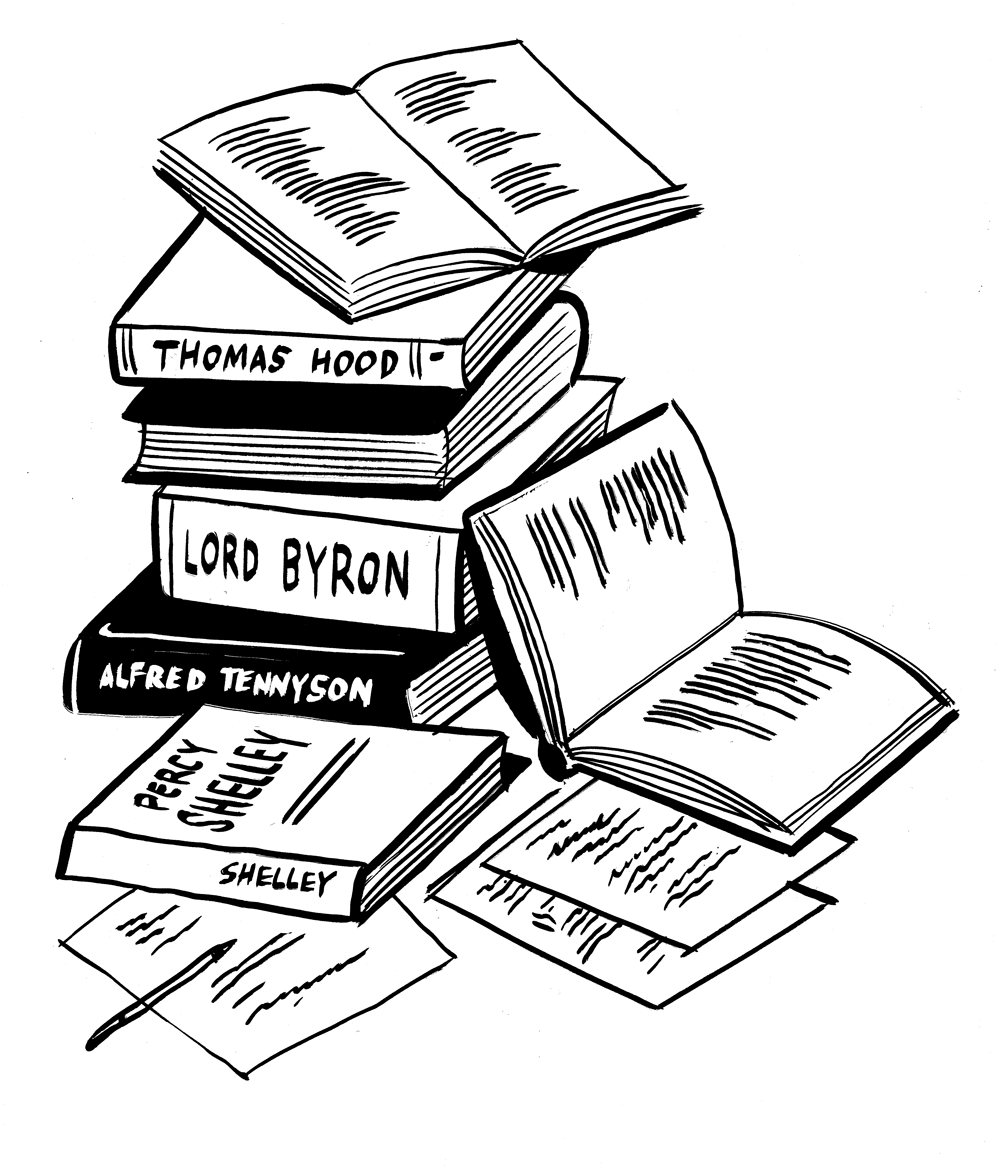

She didn’t immediately. We know that now. But her love for poetry was ignited – as it is for many – in her teenage classroom and would permeate her life and work forever. In fact, had she not been propelled into stardom that year, Marianne said that she may well have gone on to be a poet herself, or a teacher. “I had a very good English teacher when we were studying the English Romantics,” she says nearly 60 years later, over the phone from her home in London, “and I would have gone on doing that, but then I got discovered – and blah, blah, blah, my whole life changed!”

The people who helped produce it all have one thing in common: they absolutely adore Marianne.

We’re talking about poetry because of Marianne’s latest album, a spoken-word record titled She Walks in Beauty. It’s a project that’s been in the making since she was a teenager, bubbling in the background of her life, waiting for the right time to be produced and gifted to the world. Turns out, that time was during a global pandemic. The people who helped produce it were a handful of her best, most beloved friends who – music aside – all have one thing in common: they absolutely adore Marianne.

In early 2020, during that memorable first COVID-19 lockdown, Marianne was at home in Putney, in south west London. Her long-time close friend and producer Head began recording Marianne reading out a selection of poems with a mind to collect them into an album. She chose works by the greatest Romantic poets in history: Lord Byron, Thomas Hood, Alfred Tennyson, Percy Shelley. “I chose the poems that I know best and love most,” Marianne says. “I love poetry. I love the way a great poem of any kind really has got a rhythm to it – almost like a lyric, but it's not. It's a poem, but there is a beat.”

Head turned up and set up a DIY recording studio in Marianne’s spare bedroom. They aimed for three recordings a day, some poems recited and recorded in full (quite challenging for someone with emphysema) and some in sections. “Marianne reads beautifully,” Head says. “I would try and go for a short walk with her along the river each day, to get some fresh air. The weather was lovely at the beginning of March: cold but bright, Marianne is a wonderful walking companion, she has some fantastic stories to tell.” At 6pm each day, Head would finish and return to his hotel to review the day’s work.

Recording at Marianne’s house wasn’t easy. There’s a reason why recording studios don’t tend to be in city centers, and are fully soundproofed. But despite having one of the noisiest cities in the world as interminable backing singers, they ploughed on with the recordings. “It's strange, it was almost perfect for what we wanted to do,” Marianne says of the unpredictable environment they found themselves making an album in. “Head was just crucial. We couldn't have done anything without him.”

Head began to send the poetry recordings over to their friend and collaborator Warren Ellis: a Paris-based musician known for his work in the Dirty Three, Grinderman and the Bad Seeds. Head had witnessed Warren working on scoring This Train I Ride, a documentary about women who hop freight trains in America, and knew he was the man for the job. The recording sessions of Warren and Marianne’s previous collaborations – in particular Negative Capability, Marianne’s 2018 album, the title of which is a line taken from a Keats phrase about a writer’s capacity for chasing artistic beauty – were much more personal, domestic affairs.

The gang (Marianne, Head, Nick Cave, Warren Ellis, Rob Ellis and her manager François Ravard among others) would spend weeks holed up in La Frette studios, cooking meals for one another and making music in a leisurely atmosphere that seemed to almost mirror a (friendlier and less debauched) version of the Rolling Stones’ time recording Exile on Main St. at Keith Richards’ mansion, Villa Nellcôte, in the south of France.

There are photos taken of these times, of Marianne, Warren and the gang all together, leaning on each other, laughing, horsing around – images so candid they make you miss your own friends. Warren recalls times during recording sessions where Marianne’s delivery of a song would leave them all weeping. They really, truly all love one another like a family. When we think about settings that are conducive to good creative output, we imagine homely, intimate recording sessions like these. Head transferring files over to Warren to listen to in a different country during a global pandemic? Less so.

Warren received the poetry recordings during the first lockdown, in a period of time that should have seen him touring Nick Cave’s album Ghosteen. Instead, like everyone else, he was stuck at home with life very much on pause. Warren had long known about Marianne’s love for poetry, mainly because she was the one who explained it all to him.

It was this wonderful reminder of the great things that people can do, a counterpoint to all the shock horror that was going on.

Years ago, when he was working on a project about Percy Shelley for Radio France and had found the poems slightly impenetrable, he popped in to see Marianne, who was then living in her flat in Paris, to drink tea and watch TV together, as he would sometimes. He showed her the Shelley book. “I said, ‘Marianne, I can't work my way into this stuff!’” Warren recalls. “And she just picked it up and started reading it and instantly it sounded like something. I was like, ‘How do you do that, Marianne?’ and she said, ‘It's just a bloody song, Warren.’”

Warren couldn’t believe his ears when, years later, the recordings came to him during the confusion of 2020. “It was amazing being sent these, they became sort of meditations for me,” he says. “I couldn't believe my luck that they had landed in my lap and I had this work to occupy my mind. It was this wonderful reminder of the great things that people can do, and was such a great counterpoint to all the shock horror that was going on. I actually found it really therapeutic.” He played them on repeat all day, putting sounds to them and trying things out.

Marianne’s delivery of the poems hit Warren hard. In the loneliness and uncertainty of the pandemic, her wise, weathered, old-fashioned voice reading timeless poetry floored him. Marianne has always had an intriguing voice, full of gravitas and laced with life experience, like a palimpsest of the extraordinarily positive and negative things she’s been through. There’s generally comfort to be found in the sound of most 74-year-old voices, but it’s particularly apparent in the warm, husky rasp of Marianne’s.

It’s why the group that helped her make the record all agree that it was made to be delivered to an audience at the exact right time in history. We need this right now. Her voice and delivery of the poems is emotive enough to take us by the hand and simultaneously untangle the complex poems and guide us through them. By doing so, it momentarily lifts us out of our current anxiety and noise, right up and above the clouds, to a place of serenity, wonder and humbling acceptance.

Marianne can read food from a dining menu and make it sound really awesome.

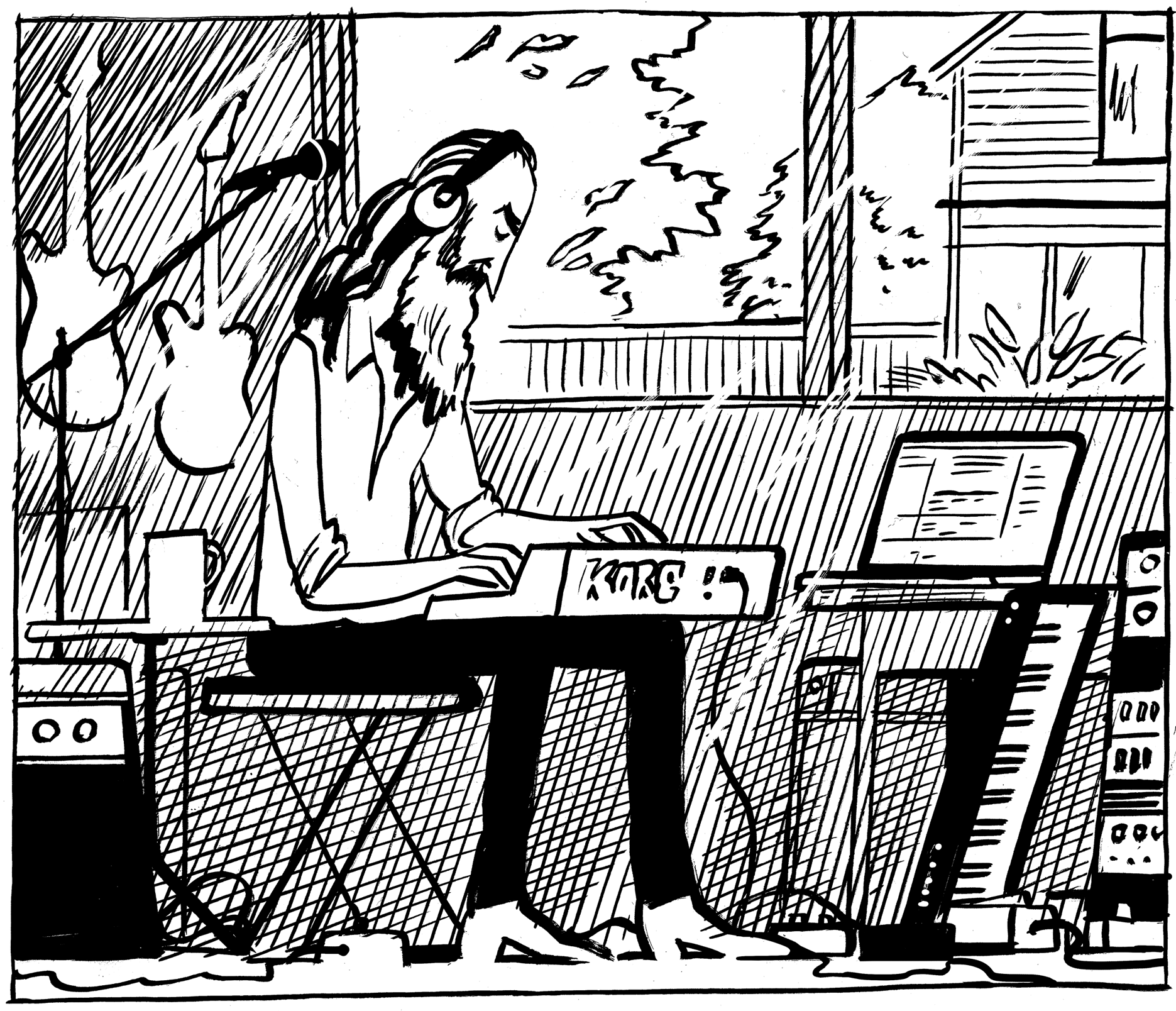

Warren listened to the poems on repeat, sometimes waking up in the middle of the night, and being compelled to work on it. “For me, it was more like putting music to image because is so evocative,” Warren remembers. “Marianne can read food from a dining menu and make it sound really awesome. Her voice is just so fantastic like that.” Warren spent lockdown in a shed studio in his garden tinkering with the sounds that would eventually accompany Marianne’s lone voice on She Walks in Beauty. “It was such a beautiful process for me...I just sat in there and listened to this stuff for hours and hours a day, just making up music for it to see what worked,” says Warren. “Some of it I made in bed in the middle of the night; I’d just make something up using GarageBand. Two of the best pieces on the record for me – So We’ll Go No More A Roving and To The Moon – were written like that.”