Growing up during Argentina’s Dirty War in the 1970s and 80s, Marcelo Brodsky had a natural interest in protest from a young age. Building throughout the years, this interest now serves as the basis for his work: the artist annotates historical photographs to show the context of the time, highlighting the issues being protested, and emphasizing the most important symbolism in each shot. Alex Kahl spoke to him about how his complicated and fearful upbringing influenced his work, and the ways in which protests throughout time are interconnected.

Marcelo Brodsky’s political education began at a young age. The Argentinian artist attended the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, the city’s national school, “an institution with a long political tradition since it was one of the first schools in Argentina,” he says. He recalls that it was a great place to find people to talk to about the country’s social problems, and to learn how to become active in changing them. When his dad gave him a Voigtlander camera at the age of 12, he began photographing his friends and family and sticking the photos in an album alongside poems he would write. “Three of these friends suddenly disappeared,” he says. “They were victims of the military dictatorship we suffered in Argentina from 1976 to 1983. My brother Fernando was among them.” From that point on, his photos took on a whole new significance.

The troubles between 1976 and 1983, often referred to in the media as ‘the dirty war’, can broadly be described as a period of United States-backed state terrorism. A mixture of military forces and unidentifiable right wing squads spent years tracking down anyone suspected of being a political dissident. Their actions were painted as an anti-communist scourge, when in fact they spent much of their time looking for students, artists and journalists; anyone with the potential to promote free speech or free thinking. In the seven years of the regime, around 30,000 people disappeared. Marcelo was himself forced into exile in Barcelona after General Videla’s coup took hold.

“The dictatorship we suffered in Argentina was the bloodiest in Latin America,” Marcelo says. “Living under that regime meant you never knew if you would return home that night. Friends were taken all around me. I was just a student, yet somehow an activist against the military regime. Repression and death were too close.” He speaks of the fear he and those around him felt, bolstered by the fact that the authorities that were previously there to protect them now presented a real danger to their lives. “There was a mixture of feelings for us. The need for resistance, but then the terror of being killed without any legal defense… anxiety, fear, despair, rage,” he says.

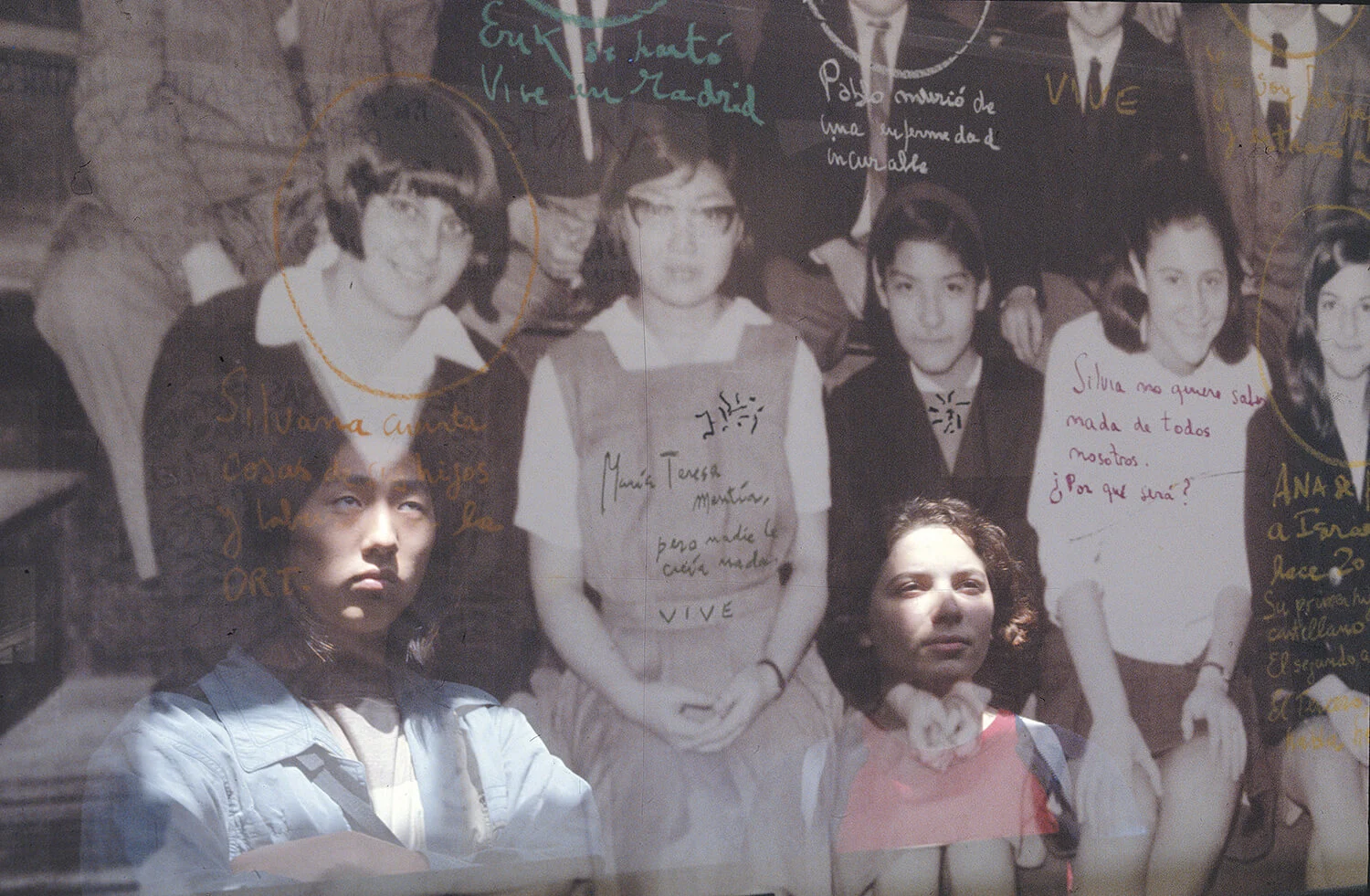

In 1996, 20 years after the coup began, Marcelo’s old school finally decided that enough time had passed to honor those who were lost. They counted that 112 students had disappeared. They organized an event in which various photos were hung on the school’s walls along with excerpts from poems and stories written by the missing students, and the names of the 112 were read out one by one, while their parents watched on. As part of this memorial, Marcelo found an old class photo of his first grade class and tracked down every person in the picture he could find. He spoke to each of them and annotated the class photo with some information about each, highlighting any student who had not survived the coup. The photo would become the first part of his project Buena Memoria, a photo-essay exploring the personal stories surrounding the seven years of the dictatorship. The photo would also pave the way for the style Marcelo would pursue moving forward, and his catalogue is now a varied selection of archive photographs with annotations, notes and quotes added over the top of them.

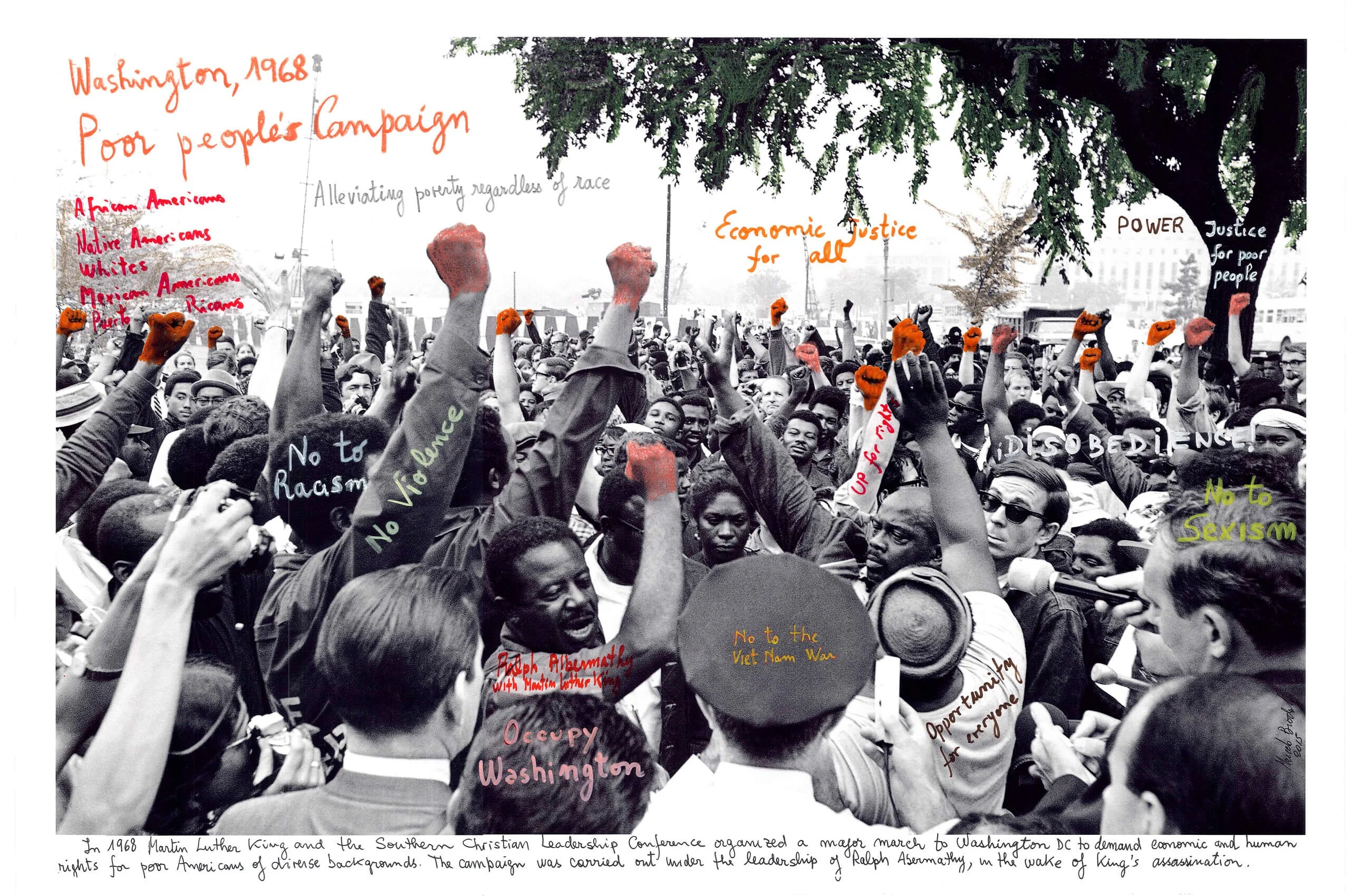

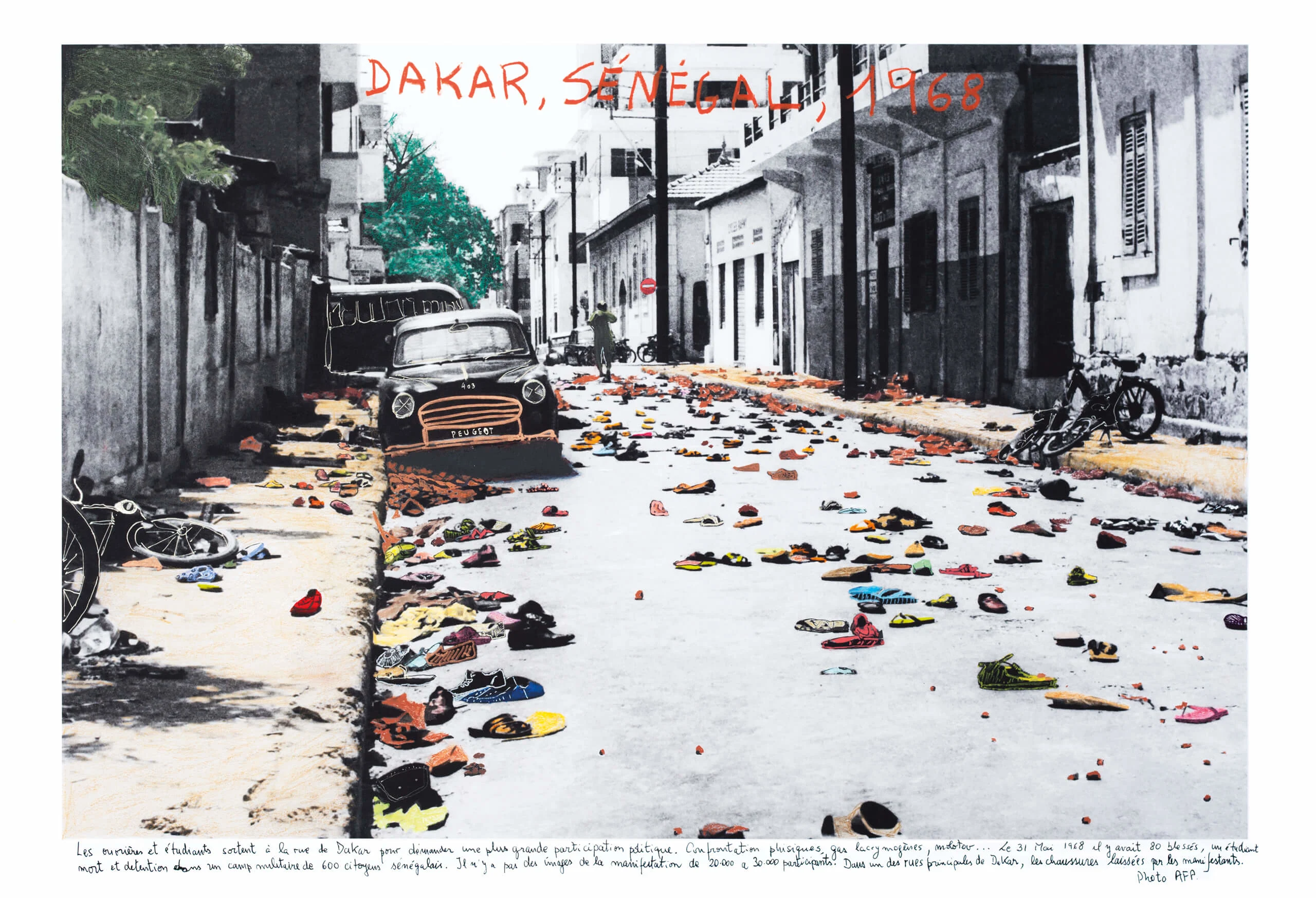

Shots from protests from Prague to Dakar — often from 1968, the year that protests took place around the world as people rose up against bureaucracy and dictatorship — are recolored, with words explaining what was being fought for at the time. A black and white photo from the Washington Poor People’s Campaign of the same year includes the fists being held in the air highlighted in red, emphasizing the power such a pose held. A shot of a peace march in Prague shows words written over the protester’s bodies, phrases such as “Stop the tanks” and “Freedom”.

Journalistic images are often the raw material Marcelo uses in his work. “Each image is different, as each reality is,” he says. “I can change the focal point of an image with my intervention: I can draw the attention to certain details that I consider to be relevant. I study each image in detail, and mark aspects that may be ignored if they are just shown as they are.”

Marcelo founded and ran a photo agency based across Latin America and Spain for 30 years, distributing photography from around the world. This work taught him about the importance of archive photography and about how images are essential in narrating history and passing on experience to future generations. “Interpreting, intervening in and working with archive images has immense potential to narrate, to create, to understand,” he says.

All social movements are more interconnected than at any time before.

Once Marcelo has done his research to find the best archive imagery for the story he wants to tell, he prints the photos on cotton paper. He looks into the context and the circumstances surrounding each image and begins to draw on the cotton. “My writing and drawing is intuitive and doesn’t follow a plan,” he says. “I sit down in my studio and start working. New meaning is added to the image, and new links are found with the other images in the essay. The narration becomes complex, diverse, extended.”

While every image in Marcelo’s portfolio says something about a different specific event, he believes that each one also communicates a more complete message about the state of protests globally. “All protests and social movements are more interconnected than at any time before. Such is the reactionary and conservative network of political forces that want to keep everything as it is,” he says. “Every protest around the world sends a message of resistance, a message that it is not so easy to get away with everything. Young people are there to offer their energy to face oppression and injustice.”

Just as one protest can share commonalities with those from the past in entirely different continents, so can one seemingly simple photo be linked to wider issues around the world, as in the case of Marcelo’s first piece, the class photo. This is his signature work, despite the fact that he did not intend for it to be art when he first made it, but rather a way to show the experiences faced by him and his friends.

“It was an attempt to transmit this experience through visual means, in an emotional rather than an rational way,” he says. “It is just based on one class, my class, but that class can symbolize our school, our generation, our country, even Latin America in the seventies. The class photo is a representation of the holes left in many generations all over the world by violence, political intolerance and repression.”