Irish hip-hop can be reasonably described as thriving. Rap has existed there in marginalized forms for most of the genre’s history. But a half-decade of artist proliferation has seen the country blossom into one of Europe’s true rap hubs. Writer Dean Van Nguyen and photographer Daragh Soden go on a road trip through Ireland to meet some of the scene’s prominent artists.

If you’re ever lucky enough to experience a tour of Limerick with God Knows as your guide, expect the voyage to be scored by grime music and energized by his enthusiasm for the city. The sounds of Skepta blast from the speakers of a mid-size crossover SUV as God darts through the narrow streets in his impressive chariot, pointing out local landmarks where he and fellow narolane Records squad members, MuRli and Denise Chaila, have spent the last decade sharpening their technique. I relax into the comfortable seat and let one of Limerick’s new-age ambassadors portray the city in alternative light. There’s no Lonely Planet guidebook that will lead you down this trail.

“We’re all 10, 15 minutes from each other,” says God as he turns onto Lower Mallow Street. “In lockdown, we were ‘bubblin’’. I ain’t used that word since we came outside.”

He points out Dolan’s Warehouse, a live venue on Alphonsus Street, shuttered at the time of our drive because of COVID-19 restrictions. “When we first started, this area was like our stomping ground,” explains God.

Pulling onto Henry Street, he directs attention to an apartment building. It’s unpretentious in every way an apartment building can be, but within its stained beige walls an important strand of Irish music germinated into life. “Literally, young me, recording up there in MuRli’s apartment, in his wardrobe,” says God. “Kyle House, that’s history right there.”

I want to bring people into my world by using my slang, by talking about the places I grew up.

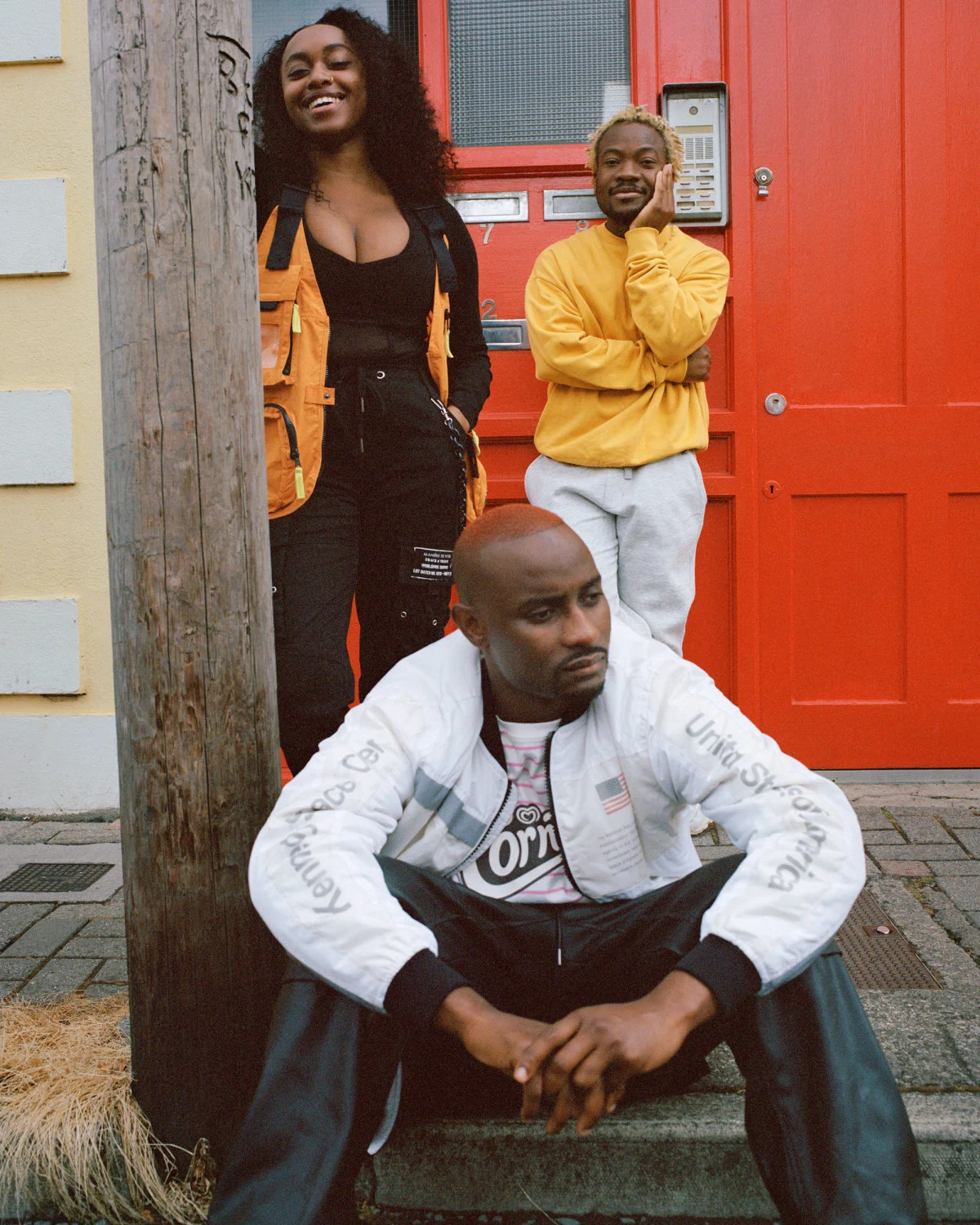

This isn’t actually a tour. God has kindly collected me and photographer Daragh, who takes the backseat, from Limerick train station, where we arrived in pursuit of the city’s mushrooming rap scene. After delivering us to Kyle Street and the company of his longtime compadre MuRli, looking preppy today with his yellow sweatshirt and backpack, God shoots off to collect Chaila, the third principal of this particular three-headed monster.

Daragh scouts locations to take photos and I think about where we’re going to have a proper sitdown dialog, which isn’t straightforward due to COVID-related limitations on what the public can and can’t do. Following God and Chaila’s arrival, and with photographs of the trio shot on an adjacent street captured on roll film, God manages to negotiate a setting with the familiar owner of the convenience store on the ground floor of Kyle House.

It’s an appropriate backdrop. Should you have a passing familiarity with Irish rap, you already know what happened after God Knows and MuRli graduated from Kyle House: the pair made their names as two-thirds of Rusangano Family, alongside producer mynameisjOhn. The video for the group’s 2016 single Lights On was partially shot in this shop. Lean in closely and you can see Chaila in the clip too, flexing in the background, waiting for her own career to launch. Five years later, the three tight-knit rappers sit down at a grubby table, half-shivering from the store-sized fridges, and with a small step ladder serving as a makeshift chair. God fetches the tea.

“I used to come down here, it was an African shop,” says MuRli, a rapper and producer for narolane. “I used to get my yam and stuff, go upstairs and cook while learning to make beats. It all happened here. And a lot has changed in the last 10 or so years.”

“We’re still here,” says Chaila, “We’re still on Lower Mallow Street.”

Irish hip-hop can be reasonably described as thriving. Rap music didn’t begin on the island five years ago—it’s existed here in marginalized forms for most of the genre’s history. But a half-decade of artist proliferation has seen the country blossom into one of Europe’s true rap hubs. With this growth has come a compelling side effect: a sense of regionalism. Until recently, Irish rap has generally been viewed as a singular entity—not entirely surprising when you consider that the whole island has a population on par with a major American city. Now, areas are forming their own distinct sound, style, identity and methodology.

Regionalism, don’t forget, was supposed to have been eradicated from hip-hop by the internet. In the US, rap matured in the 1980s and ’90s, with each city’s geography and culture reflected in its sound. It was hypothesized that technology would end all that—why would rappers automatically gravitate towards their local musical ancestors when they’ve instant access to music from all over the planet? But many current scenes have been remarkably loyal to their roots.

The difference between Irish artists and, say, the new golden era of Los Angeles rap that emerged in the mid-2010s is that they are currently developing what their regional style will be. There were few constructed norms in Irish rap to stay true to. The next generation of artists will likely build on what the current crop establishes.

narolane is among the most prominent crews in Limerick. God, MuRli and Chaila have infiltrated the Irish mainstream in a way few other home-grown hip-hop artists can boast. In 2016, Rusangano Family became the first Irish rap act to net the Choice Music Prize, an annual award for best Irish album, with Let The Dead Bury The Dead. This year, Chaila became the second—for a mixtape, no less, titled Go Bravely.

The trio are a balanced trifecta. God Knows is the showman; his disposition is infectious. When he called me a few weeks before our meet-up to discuss the details, I answered the phone to the most enthusiastic greeting I’ve ever heard—it would have fit right on a song intro. MuRli is a more calming presence, which you’d expect from a guy who spends more time beneath headphones, crafting beats. Yet he’s measured only until the point he has to perform, when he ignites into life. As for Chaila, she’s cultivated a following for her philosophical nature. A lot of people with no interest in hip-hop were first introduced to the star last year when she appeared on chat show The Late Late Show and spoke about issues that affect her as a Black Irish woman. (Chaila was born in Zambia, God in Zimbabwe and MuRli in Togo. All three settled in Limerick as kids.)

It was narolane that moulded one of the most prominent Irish rap projects of 2020: Whose Asking? God Knows had already cut a solo version of the swamping grime-inspired banger when a thought pinged into his brain: this would work as a crew rap joint. A platoon of rappers from Limerick were recruited to lay down verses—namely Chaila, Hazey Haze, Citrus Fresh, Gavin DaVinci and Strange Boy—and Whose Asking? (South West Allstars Remix) was forged. Recognizing he was on to a good thing, God followed it up with Who’s Asking? (East Coast Allstars Remix), featuring Dublin rappers Nealo, Mango and Rebel Phoenix, and Wexford star Skripteh (when God Knows puts out a Bat Symbol, people answer the call). The beat was the same but the accents, flows and cadences were totally different—the disparity between two rising regions laid out clear as crystal. Listeners were invited to consider which sub-scene has the best rappers right now: the South West or East Coast. Everyone wins when there’s a little healthy competition.

“The ethos I have is that everyone here is sick, everyone’s been doing it a while, everyone who was on any of those records, they were all killing it in their own space,” explains God. “And they own that space. No one can be Hazey, no one can be Denise, no one can be Citrus. Everyone is their own superhero.”

Limerick rap is hardly monolithic. Take Strange Boy: with an extremely heavy accent, he raps over beats that borrow from traditional Irish music, a strange seance that summons the island’s beloved balladeers for guidance as much as it does Rakim. God Knows is a disciple of UK grime; MuRli’s orchestration frequently incorporates West African-style percussion sections.

What does bind Limerick rap is a sense that the record must be corrected. For years county Limerick—of which the city serves as the capital—has been unfairly vilified as a violent and crass backwater, and not the diverse land of 200,000 people that it is. Just recently, an article in Forbes about Limerick natives Patrick and John Collison, founders of online-payments company Stripe, invoked the worst stereotypes by calling the city “the murder capital of Europe”. Redact the specifics and you might have mistaken the piece as a description of Mega-City One from the Judge Dredd comic books. “Limerick is the last place you want your kids growing up,” read the piece. (Forbes later said the article did not meet its standards). It’s that misrepresentation that narolane feels is behind the rise of Limerick rap. The demonization inspired Chaila’s single 061, named after her hometown area code.

“We came from the 061, we’ll show you how to get things done,” Chaila raps, over the MuRli-produced beat. The lush, fantasy-themed video sees Chaila shapeshift from Elven princess to flaring red-haired, sword-wielding warrior, with cameos from some of Limerick’s most prominent creatives, including singer Emma Langford.

“There’s power in mutual recognition and in claiming something,” says Chaila, adding sugar to her tea. “Because this is a place where people have been disparaged. I saw an article in school that said Limerick is the waste basket of Ireland.”

“Oh, jeez,” sighs MuRli, sitting next to her.

“And then there’s all these Vice documentaries painting Limerick out to be the slums,” continues Chaila, “and everyone is shooting and drugging and drinking over here, and I was like, ‘That feels wrong, that is not the place I know.’ This is really a very nuanced, very layered place with a lot going on and far, far more than the sort of two dimensional.”

“The reality on the field is very different to what people say, what the perception of Limerick is around the country,” says MuRli. “There were all these stereotypes people would say about Limerick: ‘Oh, you wouldn’t dare go there, jeez, how do you live in Limerick?’ Have you been to Limerick?’ So I think in a way it unified us.”

Similar thoughts swirled in Hazey Haze’s brain when he wrote his own dedication to Limerick, This Is My City. Hazey was initially hesitant, as he didn’t want to do what he describes as “a cocky, braggadocio tune”. But when he heard the tempo of the beat—a hard, bass-heavy thing—he was in what he describes as “proud but angry form” and embraced bravado. You can’t stay humble when spitting about your “kingdom.”

“This is my city,” yells Hazey throughout the track. “This is my home.”

Hazey hails from St. Mary’s Park, aka Island Field, a housing estate built in the 1930s. He describes himself as an “Island Field Limerick man before I’m a Limerick man”. I catch up with him at Dry Lane Studios, a fantasy cave right in the heart of the city, next to what could be the biggest sex shop in Ireland. The space has a relaxed, college-dorm-room feel. A myriad of percussion instruments sit next to a small shelving unit with about 15 slouching books. The giant image of a psychedelic sun gazes from a wall behind crimson leather furniture. The interior decorating style is kush. Operating so centrally, Hazey feels connected to the city, and it seeps through into his music.

“When I’m shouting out Limerick, it’s not the Limerick that you know, because it made us,” says Hazey, his thick beard and hat failing to obscure the passion for his craft in his eyes. “When you talk bad about Limerick, that means you’re talking bad about me.”

Hazey is another of Limerick’s elder statesmen of rap. He was part of the group Same D4Ence, founded in 2013. Back then, spotting a rapper in Limerick was akin to catching a glimpse of an albino alligator, Scottish aquatic monster, or novelist Cormac McCarthy. “I used to get enough slagging for being a rapper,” says Hazey. “I’ve been doing it for nearly 10 years, and eight or nine years ago people were just wondering what are you doing. Now they’re like, ‘You keep doing what you’re doing, you’re doing amazing.’”

It’s an anecdote that speaks to the increasing credibility of Limerick rap. Together, the community is laying down gauntlets and setting new standards. MuRli predicts parallels between Ireland and Great Britain, which is years ahead in terms of rap development, but has cultivated styles that can’t be confused with any other nation.

“The joy of collaborating and not just being stuck in your own little corner is that eventually we will get to what the defining sound of not just Limerick rap, but Irish rap, is going to be, if there’s going to be one,” says MuRli.

“If it bangs for everyone, great,” adds God Knows. “But it bangs for us.” narolane are unashamed about their desire to go global. But like Kendrick Lamar will never not be Los Angeles, Chance The Rapper will never not be Chicago, and Stormzy will never not be South London, they’ll never not be Limerick.

“For me it’s pretty simple, actually,” says MuRli. “The international thing, it’s just exposure. But what is the international audience being exposed to? It’s not going to be my international life—it’s my local life that I’m taking to the international audience.”

“MuRli, ladies and gentlemen!” yells God Knows in approval, his voice filling the shop, shaking Kyle House.

Says MuRli, “That’s something we’ve talked about for a time—think globally, act locally.”

It’s been thrilling to watch the narolane crew net mainstream traction. That doesn’t mean you can trust the mainstream to pay tribute to all deserving innovators. There’s the stars of Irish drill, a blood-raw subgenre that borrows from a UK street sound (which itself borrowed from the drill-music innovators of Chicago) being blazed by artists in their teenage years and early 20s. To be fair, almost everything about Irish drill is a rejection of the mainstream. Its most prominent artists, like their UK counterparts, often favor masks and anonymity. Even before COVID-19, live shows were a rare occurrence. And the music itself is murky, violent and totally unsuitable to the portal of daytime radio. Yet enter this shadowy world via the window of YouTube and you’ll find yourself joining the legions. Views on an Irish drill track can rack up in the millions.

Despite appearing to exist primarily on the internet, there are some geographical drill strongholds. Athlone, right in the center of Ireland, has been a cradle to artists like J.B2, JugJug, and Cubez. But the capital of Irish drill might just be east, in County Louth, where stars are poised to contradict convention and break out. Reggie (sometimes known as Reggie B) hails from the town Dundalk. On last year’s single My Accent he looked every inch a star, the lyrics revealing his ambitions to represent his home nation globally: “I’m Irish and I wanna speak, ’cause I wanna reach like Michael Jordan.” And in Drogheda, you’ve got the A92 crew, which became the first Irish drill act to enter both the Irish and UK singles charts, with the song 92 Degrees. A92 are part of Trust It Entertainment, which over summer cut an impressive deal with Atlantic Records. (Still, the group are shrouded in mystery. I failed to pin them down for an interview for this piece.)

“I’d like to see it go very far,” Reggie told me in 2019 when asked on the future of Irish drill. “I’d like to see it make people recognized. I’d like to see it employ people—I like to see music employ people and take them out of bad situations. Yeah, I’d like to see it go that far.”

About halfway between Dundalk (in the north of County Louth) and Drogheda (in the south) sits the smaller Ardee, population less than 5,000. Not even this tiny town has been shielded from Louth’s hip-hop boom. Among its artists are Steo Skitz, a relative veteran. There’s Kebz, a member of A92 who attended the local school here. And there are RÓGAN and ØMEGA, who see themselves as pitching somewhere between drill and Travis Scott’s wrought-iron trap, though I detect some Eminem in their hardcore sound too.

“It has a big castle in the middle. Apart from that, it’s known just because of the fact it’s where the N52 and the N2 meet,” explains ØMEGA (real name, Thomas Gillespie), struggling to think of anything else noteworthy to tell me about the town. To a first time visitor like me, it’s the kind of charming town you’ll find dotted around the country. Photograph it at a particular angle and with the right digital filter, you’ll get something that could pass for the 1950s. Call it tangential but RÓGAN (aka Gary Byrne Jr) has heard that an Irish pizza-chain outlet here may well be the best in the country. So there is that.

“It’s just a typical Irish town where everybody grew up, became who they became and just lived out their lives,” says Gillespie. The pair speak to me in a public park on the edge of the town.

Adds Byrne Jr, “You’ll either stay here or you’ll never come back.”

That doesn’t totally stand up to scrutiny. Gillespie was born in Bristol and as a child moved to Ardee after his father decided to return to his hometown. Byrne Jr moved here as a kid without any roots in the area. The pair met in school and began a collaborative relationship, which evolved over time into a formalized partnership. In the beginning, rapping was an unusual thing for a person in Ardee to be doing. Gillespie claims he has been “jumped” just for being a rapper.

“In this town, you’re on a conveyor belt,” asserts Gillespie, now aged 25. “You got to that school,” he says as he points to the local school, “then you got to college in Dundalk, and you come back and you work in either the potato factory or Centra [a convenience store chain]. And that’s it for the rest of your life, and the minute someone tries to come off of that conveyor belt. They’re like, ‘Do you think you’re better than me?’ No, I’ve different aspirations in life.”

Gillespie blesses himself as an ambulance roars past the park, a common Irish superstition. He wears a jacket he custom-made himself that bears the branding of Jay-Z’s 4:44 album and a pair of shoes decorated in Drake logos. He transitioned from pop rap after discovering trap music, a style he feels exercises his pen better. His process typically sees him go for a walk around Ardee with the beat playing in his headphones, ensuring the town seeps into his writing. Having constructed a studio in his own bedroom, RÓGAN x ØMEGA managed to record and release three EPs during the various COVID-19 shutdowns.

Gillespie recalls, “We took the lyricism of the stuff we listen to—I listen to Jay-Z, I listen to Benny [The Butcher], I listen to that type of ’90s-inspired hip-hop—and [wondered] if you brought it to the modern day, what would the beats sound like?”

Says Byrne Jr with a laugh, “I remember years ago you did a song and your dad was like, ‘Where did all this aggression come from?’”

Visiting this small oasis of rap enterprise in mid-Louth crystallizes one important thing: the resourcefulness of young artists. But such grassroots movements can also be fragile. RÓGAN x ØMEGA would like to see more financial support come through from those in power.

“One thing I am coming to terms with is how difficult it is to be a creative in Ireland at the moment in terms of support,” says Gillespie. “Even inside Dublin it’s quite difficult, but go ask the Arts Council of Ireland to back two lads who live here. They’re not gonna do it.”

When out-of-towners picture Dublin, it’s the city center that conjures in their minds—the romantic vision of the Irish capital you see on postcards. Photographs of the River Liffey are posted to Instagram approximately 3,285 times a day. The area, in theory, should be the hub of Dublin rap, and an epicenter for Irish rap. But venues are being shuttered. Gentrification is erasing the city’s character. A corporate monoculture is forming, and creatives feel they are being cast out. For a number of years now, the housing crisis has been like a giant palanquin on the backs of a whole generation.

Rather than allowing themselves to be deleted, Dublin rappers have used their music in protest. Mango X Mathman were once staples of the Bernard Shaw on South Richmond Street, a pub for creatives and bohemians where Mathman ran a regular beat competition to showcase rising rap producers until it was shuttered in 2019. Mango X Mathman’s album Casual Work documented a city in the process of having its DNA altered by capitalism. Then came Nealo’s All The Leaves Are Falling and Kojaque’s Town’s Dead, two records that depict wealth inequality, the hollowing-out of Dublin and a generation left behind.

To the south of the city is Kimmage, a leafy suburb. There you’ll find a studio with no detectable online presence. If you know which two houses the small building sits between—and listen closely for the hard-angled synths and booming bass reverberating through the concrete of the street—you can find a rapper readying the next great Dublin album.

Inside, Rebel Phoenix and his producer Adam Byrne preview Kaleidoscope for me, the opening track from his upcoming project, Museum. It’s a gritty, mid-tempo noir piece full of atmosphere and intensity. Rebel criticizes the police and calls for revolution.

“From a fair city where there’s bare knuckle scraps/Seen it all from the streets to the stairs of the flats.”

Maybe it’s the words, the cadences and the accent, but the music sounds like it could be bouncing off Dublin buildings, conjuring images of rain-streaked roads under streetlights.

“I just feel like I want to bring a whole new level of artistic value to rap music,” Rebel says boldly, “and that’s the whole idea of this album being called The Museum.”

Rebel’s discography runs pretty deep, with various releases stacking up on his Bandcamp page. I’m particularly partial to Global Warming, the 2019 joint EP with producer Marcus Woods that saw Rebel rap over fizzing electronic beats. But he envisions The Museum as his seminal album—the one that’s going to launch him higher.

“I just believe in it more than anything else I’ve ever made, and I’ve spent more time on it than I have on anything else,” says Rebel on Museum, which he’s hoping to drop next year. “All over the place there are different albums coming out from different people and they’re all such high quality. But I just know that I have something to offer that other people don’t, and it’s the poetic value and the versatility, so I want to just put that into one record.”

Rebel is imposing physically, that’s for sure. Dressed in a Malcolm X tee and Supreme hat, he’s particularly striking on the day I stop by the studio. To be in his presence is to recognise star quality, a valuable commodity in building a rap career. He’s heavily tattooed. When it comes to carefully planning his tattoos or getting ink on a whim, it’s “a bit of both”.

“My music is a bit of both as well,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll just shell off and talk my shit. For the most part, I’m definitely deliberate. There’s an underlying meaning in a lot of what I do.”

After we listen to another song, a more Southern rap-inspired cut, Rebel is reminded of a specific tat by one of the lyrics. “I mentioned the tattoos there—‘I’d rather die on my feet than to live on my knees’—that’s what they mean,” he says as he points to the star design inked on his knees. “It’s a Russian prison tattoo. They get that, and that says I will not kneel to authority, so that’s the rebellious thing. And it also means I will walk where I want. These nautical stars, it’s a compass.”

Rebel, originally from the west Dublin suburb of Palmerstown, was drawn to hip-hop as a kid, when MTV provided a portal to Dr. Dre. He credits his babysitter, Muireann, for sneaking him a copy of the (extremely explicit) Dre album 2001 behind his parents’ backs. Later, his brother bought him a Wu-Tang hoodie. Never mind that he didn’t know who the group were, he was soon hooked on the Clan.

I made it seem like it was a journey to the ISS: the International Space Station. But it was actually the journey to being an international superstar from Dublin.

Coming of age, Rebel began penning lyrics. His cousin’s half-brother is the rapper Jambo, and young Phoenix started finding his voice in Jambo’s studio. He released a collection for free on Bandcamp in 2014, a set of boom-bap-inspired tunes.

It was Rebel who was approached by God Knows backstage at a show and asked to pass on the message of* Who’s Asking?* to some of the other Dublin rappers. His style was perfectly suited to the track: gruff and accented, he exudes the city. He wants Dublin to remain central to his ethos as he seeks a larger audience.

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re from Dublin, any county in Ireland, England, Europe, whatever. If you can understand what I’m saying you’re pretty much going to relate to it. But I do want to represent the people in my city. It all stems from that, that’s where it all grows from, from Palmerstown. All the stories of the people I was surrounded by, I’m doing it for myself, for them, I want to tell their story, I want to represent them.

Rebel Phoenix does make music that rings of Dublin, that’s undeniable. But it also begs the question of what Dublin rap sounds like. There’s no tidy answer. Take BoyW1DR, who is based right in the city center but spends most of his time in the large suburb of Blanchardstown, which has seen a cluster of activity. BoyW1DR’s effects-drenched vocals speak his sullen thoughts and depict a soul frayed at its edges. With the rapper’s ability to make everything tuneful, coupled with futuristic, midnight noir beats, the decay of the human psyche has rarely sounded so beautiful. To my ear his biggest sonic precursor is Future. Yet it was Isaiah Rashad’s pen in particular that convinced him to pick up a mic.

“It reassured me that someone else is going through similar things,” he tells me over daytime outdoor drinks at the Button Factory, a Dublin venue that has hosted Raekwon and Freddie Gibbs, among others.

Transatlantic influences aside, BoyW1DR was inspired by what was happening around him. His emergence is evidence that Ireland’s local rap scenes are becoming self-generating, as artists look to their elders. “I remember in 2015 it was impossible to miss. There were so many collectives in Dublin doing their thing,” he says. “Hare Squead were making music—Jessy Rose’s from Blanch, he was like an elder who we’d see coming in and out of the studio, except he was already signed, he was like a hero.” BoyW1DR’s relative youth is reflected in his stage name, a homage to Batman’s closest ally. “The reason I called myself BoyW1DR is because everybody knows Robin and they call him the boy wonder because he was 12 when he started being Robin, but he fought the Joker, he fought the Riddler, he was keeping up with them… So, I felt like regardless of whether I started earlier or later, you’re going to respect me the same way evil villains need to respect Robin.”

That’s the next step for many of these artists. They’re vanguards for their cities, yes, but now is time to become international ambassadors. For now they continue to show and prove, setting new standards. There is only forward.

“It’s like when you listen to, say, a New York rapper and they’re talking about the streets that they grew up on or they did their thing on, you want to hear that because it puts you there,” says Rebel Phoenix. “So I want to bring people into my world by using my slang, by talking about the places I grew up. I mention watching people watch cars under the M50 bridge. That paints a real picture of what’s going on in Dublin. I love to do that in my music. It’s definitely happening more in the Irish scene, you can see the likes of Denise Chaila and the Limerick crew, or wherever it may be. Up in Belfast, all around the country, people are representing their own areas. It’s all under that umbrella, but there’s so many different elements of Irish hip-hop and they all stand out, stand in their own lane, and represent where they’re from. I love seeing it. It’s important. It’s what rap is based on, representing who they are and who they’re from.”