Despite 30 years having passed since the fall of the Soviet Union, the marks it left on the countries that were in its clutches haven’t faded. Bulgarian photographer Eugenia Maximova’s project, Of time and memory, sees her exploring houses and apartments across post-Soviet countries and capturing their interiors. Their “kitsch” style has links to the totalitarianism of the Soviet era, and this aesthetic may often have negative connotations. As Eugenia tells Patricia Couvet, though, her series is a reminder that there are of course happy memories attached to these homes, and that their design is emblematic of a community who shared their experiences living in the shadow of the regime.

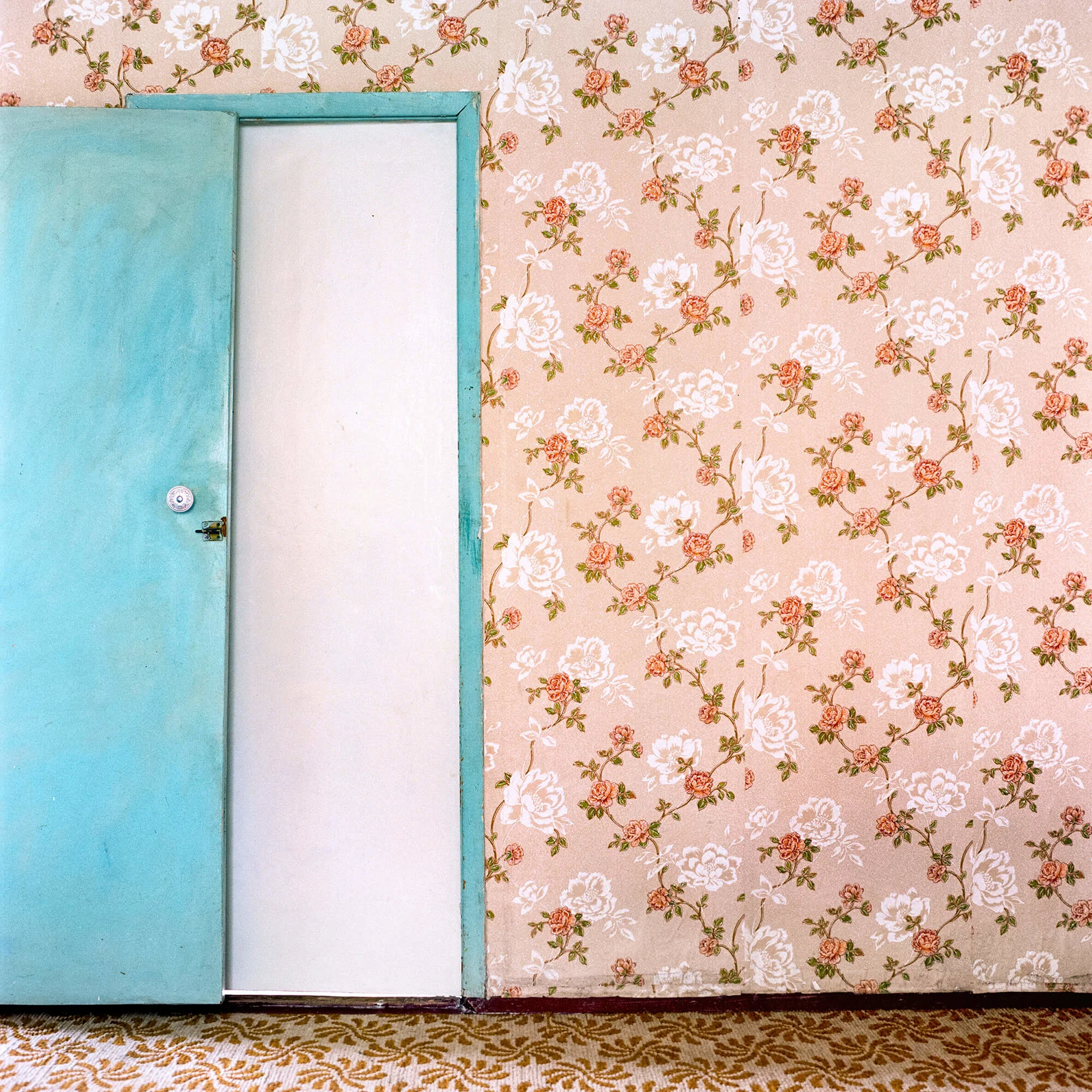

In her series, Of time and memory, Vienna-based photographer Eugenia Maximova shows home interiors – kitchens, bedrooms and living rooms – frozen in time somewhere between the 1970s and 80s. Clocks and calendars hung alongside black-and-white photographs on the wall allude to the passage of time in what most westerners consider “Eastern Europe.” Taken across multiple post-Soviet countries such as Ukraine, Moldova and Russia, the project is an ode to the unexpected beauty of “kitsch” patterns, and the intimate relationships we have with old, forgotten objects.

Born in Bulgaria, Eugenia moved to Vienna in the 90s. “I was one of those ‘economical immigrants,’ and I came to Vienna to study, to work and to escape the situation in Bulgaria,” she says. Back then her native country on the coast of the Black Sea was facing an economic, political and social crisis, and Eugenia feels this hasn't changed. Between 1945 and 1989, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria was ruled by the Communist party. Since the country became a part of the European Union, Eugenia’s childhood memories are rooted in an ideological world that no longer exists.

While living in Vienna, Eugenia started to develop an interest in photojournalism, and gradually taught herself the ropes. “I was just so curious,” she says. “After I bought my first camera, I started to photograph myself and experiment.” It was in 2012 after taking part in a masterclass, run by Noor Agency and supporting young photojournalists and documentary photographers, that she started the ongoing project Of time and memory. Educated in a Russian school, she speaks Russian fluently, and the language is still at the center of a transnational network which she navigates throughout the project, from the Baltic to Ukraine, from Central Asia to the Caucasus.

For me, it was so beautiful to rediscover my own childhood in these old traditional interiors.

The homes Eugenia photographs are the apartments and houses of friends, but also of friends of friends, their relatives and their neighbours, so every now and then she'd be entering the home of a complete stranger. Her visits often started with some tea in a cup ornamented with painted flowers. There are no people in the pictures besides those in the black-and-white photographs that hang on the walls. In one of the pictures we see high-heeled shoes reminiscent of a scene from a wedding whose date is indeterminable. “This is a huge apartment in the center of Chișinău,” Eugenia says. “The owner only stays there for a few weeks every year, so nothing has been changed or repaired over the years.”

During her trip to Chișinău in Moldova, she recognized the same objects that had been so prevalent in her own childhood. The friend’s place she stayed at was like a sibling to her own “museum of memories.” In one picture, two dolls sit next to a gramophone made by the brand Akord. “I had the very same gramophone and dolls when I was young,” she says. “It was like taking a trip to my own childhood.”

People are starting to rediscover their own culture as something positive that has value.

In her project statement, Eugenia writes that people often “dismiss kitsch as an aesthetic no-go,” but her photographs want to explore the ties between totalitarianism and kitsch. “Back in Soviet times, kitsch was the most widespread and often the only affordable form of art or design,” she explains. The project is both autobiographical and anthropological, not only capturing this aesthetic from the past that seems outdated, but also trying to dig into people’s emotional and psychological attachment to that aesthetic, which was such a prominent part of so many people’s lives. “For me, it was so beautiful to rediscover my own childhood in these old traditional interiors,” Eugenia says.

The pervading cultural and ideological system shaped daily life in the so-called “Eastern Bloc,” and this also applied to the field of design and production, leading to a lack of variety or choice in these fields. You might find carbon copies of western items, or some brought back from travels to the west, in people’s homes. These objects were seen as symbols of prosperity, and would be shown to any people who might visit your home. In the photos, you can sometimes spot these objects from the periphery of western lifestyle, such as pop stars pinned on the wall and stuffed toys sat on the shelves. Eugenia speaks of “a climate of disbelief and a lack of trust” that was felt by many people towards the Soviet ideology, and how this led to a fascination with western material culture, as it signified the idea that, somewhere else, people lived better lives.

For Eugenia and for many others who lived in now post-Soviet nations, these photos are emblematic of a style they were compelled to adopt long ago, and one which may sometimes have negative connotations for them. As she made this project, though, and was welcomed into these homes by friends in familiar ways, she offers a reminder that this aesthetic is a connecting point between her and so many others.

One often feels nostalgic about the places one leaves behind, and Of time and memory explores the archaeology of these places, emphasizing the fact that these homes some people might consider “kitsch” are in fact emblematic of decades of shared experiences. “We’re starting to overcome the gaps, both economic and societal, between west and east in Europe,” she says. “Now people are mixing items from both sides, and starting to rediscover their own culture as something positive that has value.”