The definition of masculinity may now be in a state of flux, but throughout history manhood in art and photography has taken on many forms, from the fluid to the vulnerable to the stereotypical, all of which have contributed in some way to how men are viewed in society. In line with one of 2020’s biggest exhibitions at the Barbican in London, Douglas Greenwood examines these changing perceptions through photographers and their subjects, unpicking the past to predict the future.

Cover image (top of page): Sunil Gupta, Untitled #22 from the series Christopher Street, 1976; Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

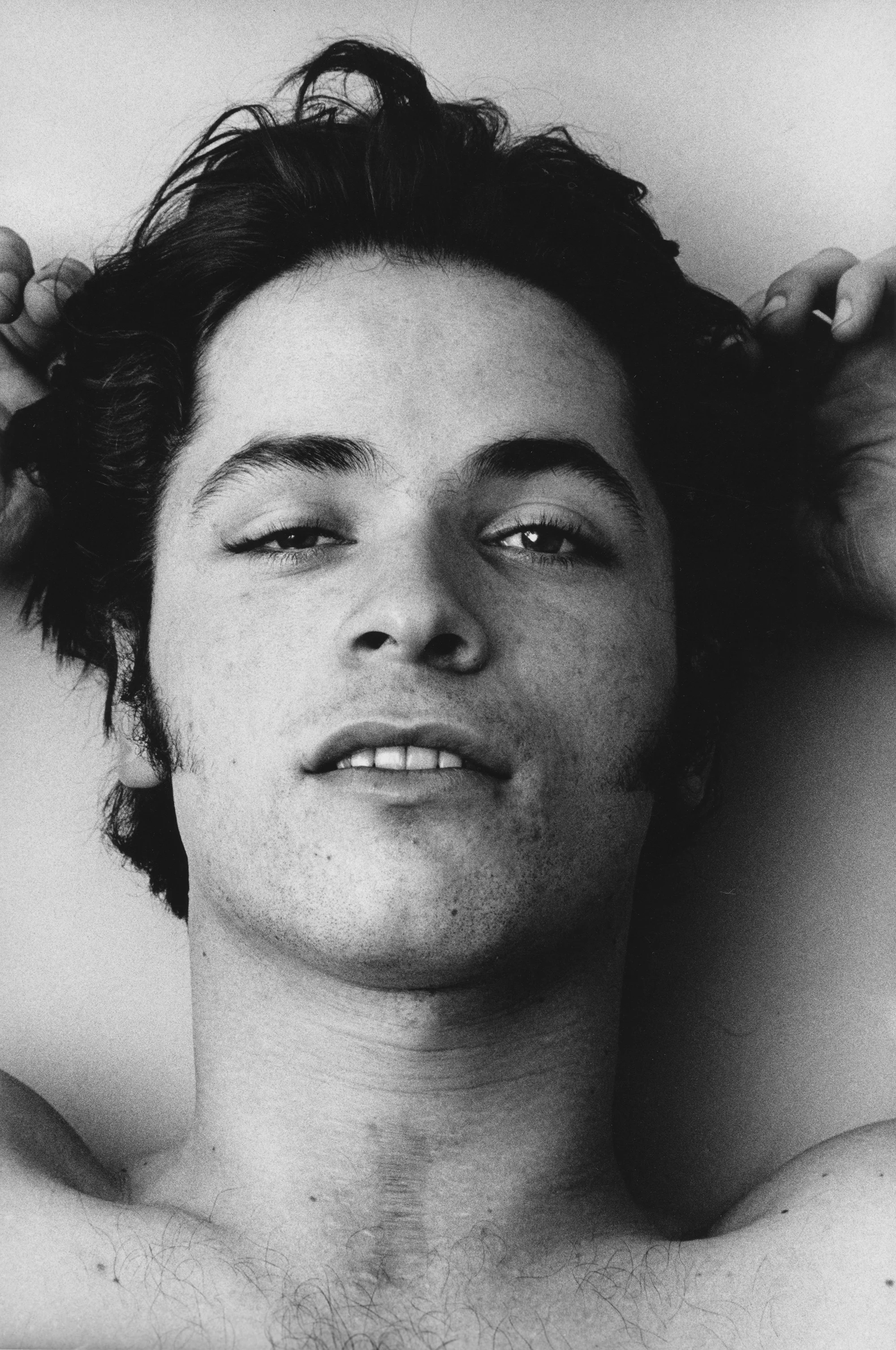

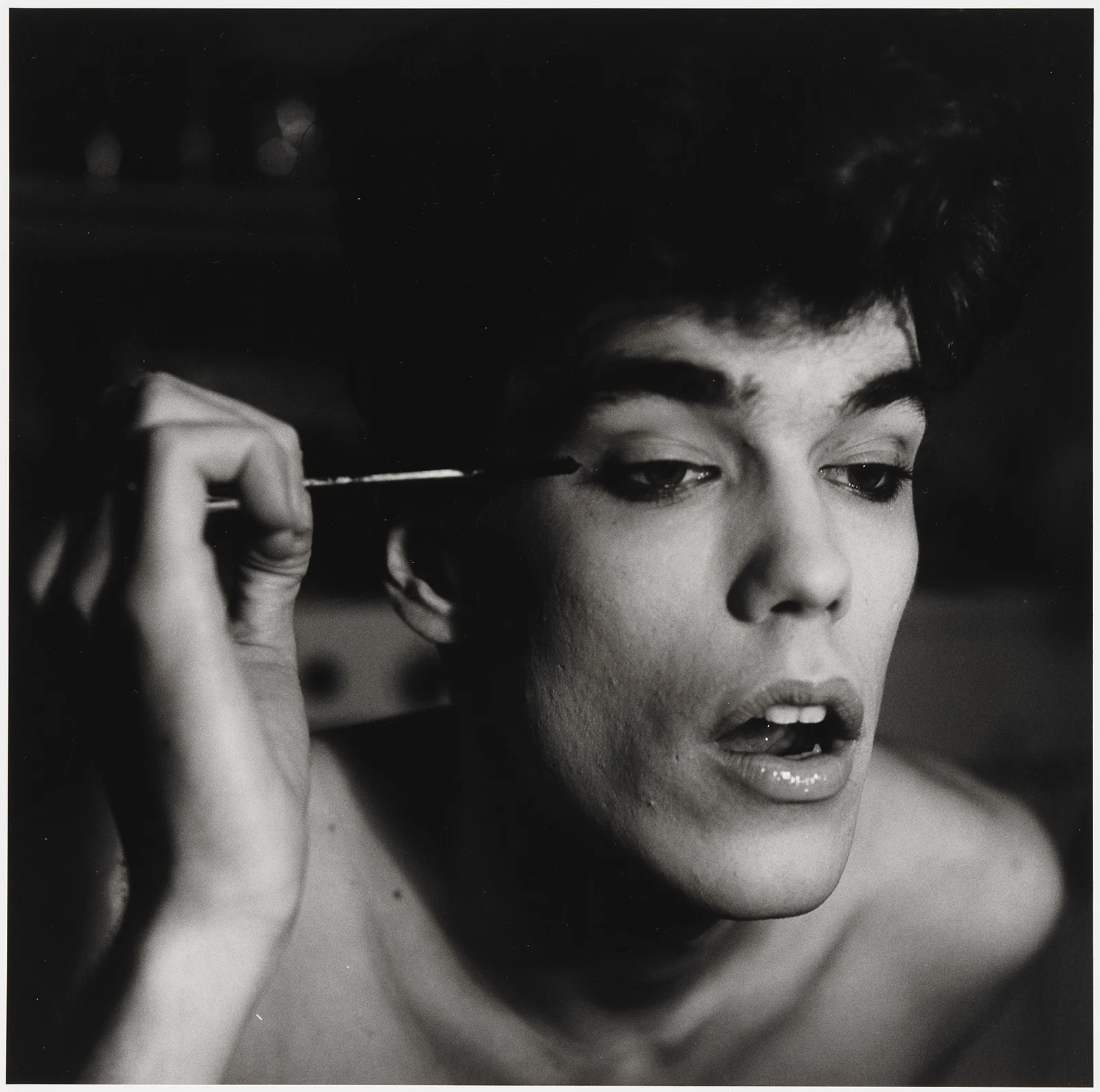

A man lies on his back, hair matted and messy as his hands lightly grip it. His head juts backwards, exposing flecks of wiry chest hair. Slightly out of frame, the suggestive shrug of his muscly shoulders achieve their fullest, most attractive form. His eyes, the right one slightly lazier than the left, hint at a hidden ecstasy as his lips part to let out a sigh of relief. A tingling dose of testosterone is coursing through his bloodstream. But in this moment, the man is disarmed; vulnerable.

The picture in question — Orgasming Man, part of a triptych that portrays men in varying states of sexual satisfaction — was taken in New York in 1969 by the late Peter Hujar. It was his friend, the writer and artist Susan Sontag who once said that “what is the most beautiful in virile men is something feminine.” She must have found that in his work. Hujar’s portraits of men – some lovers, others subjects he was drawn to – found softness and glimmers of femininity in the man of the mid-20th Century. He was one of a handful of photographers, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz included, who subconsciously subverted the notion of masculinity as a simply stoic thing, way before such qualities seeped into the mainstream. Nowadays, work that pays tight homage to the queer masters of yesteryear is commonplace. Ryker Allen, the non-binary New York photographer, captures the queer subcultures that have edged forth since Hujar’s death, and the lenses of Coco Capitan and Alasdair Mclellan famously capture men of all frames in stark, unsexualised nudity.

Recently too, we’ve seen this shift out of photography and into the styling and aesthetics of modern celebrities. There are hints of it in the presence of Harry Styles, the modern alt-pop icon who, with the assistance of his stylist Harry Lambert, has transformed into a shining beacon of aspirational modern masculinity: both sexy and soft. Even rap music, a notoriously stoic space, has loosened up. Tyler, the Creator has become one of the most respected queer artists today, with his Liberace-like live shows, peroxide wigs and colourful suits epitomising camp. It’s a huge switch-up from his early days as a roguish, some argued homophobic hip hop entity.

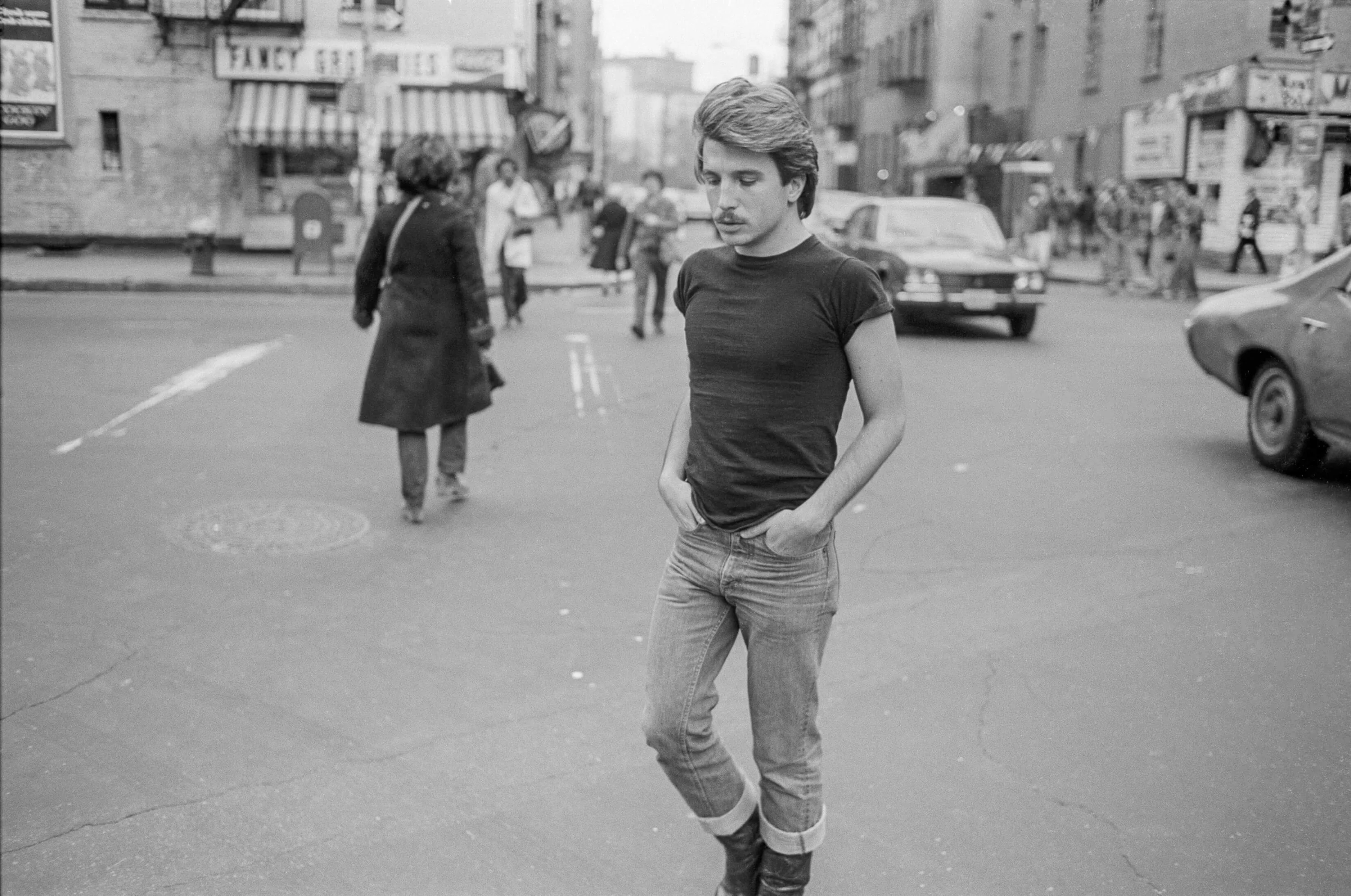

When we consider the stereotypical western man of Hujar’s era – post-World War II, returning to the ideal of the White Picket Fence lifestyle – the image in our heads feels like a far cry from one of the photographer’s subjects. This stereotype is straight-laced, sexually dominant and in command; afraid of being seen, in any way, as fragile.

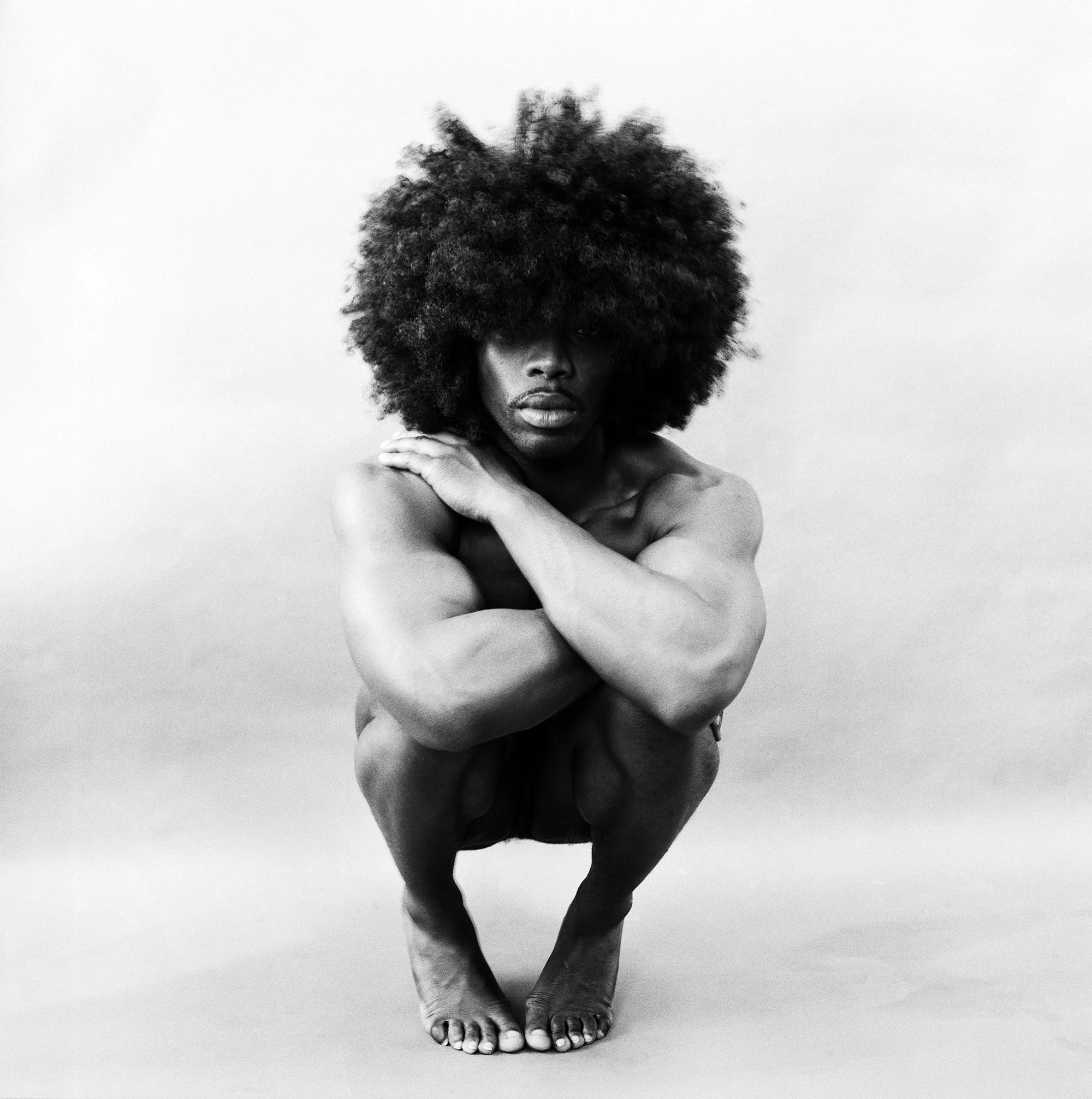

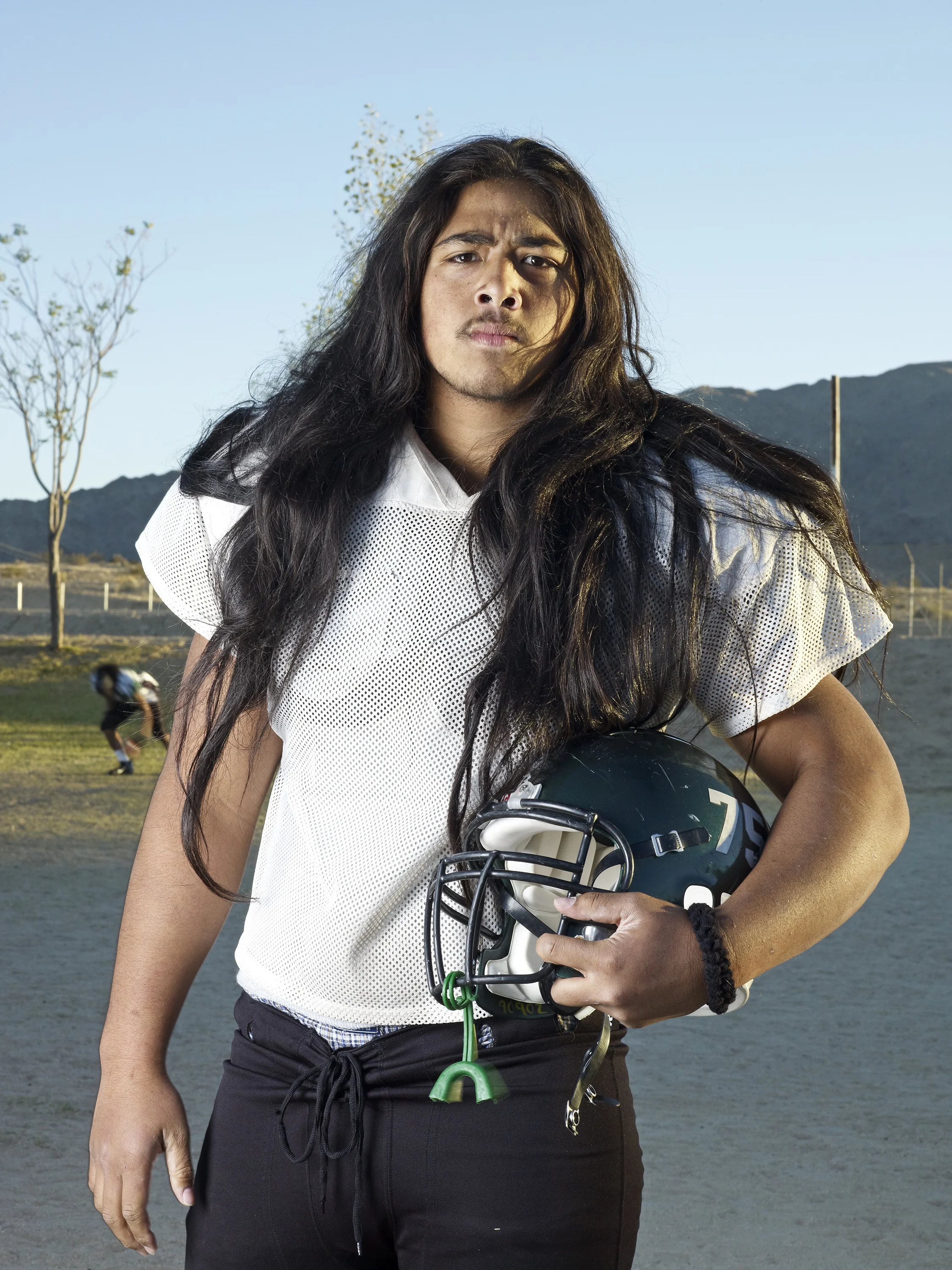

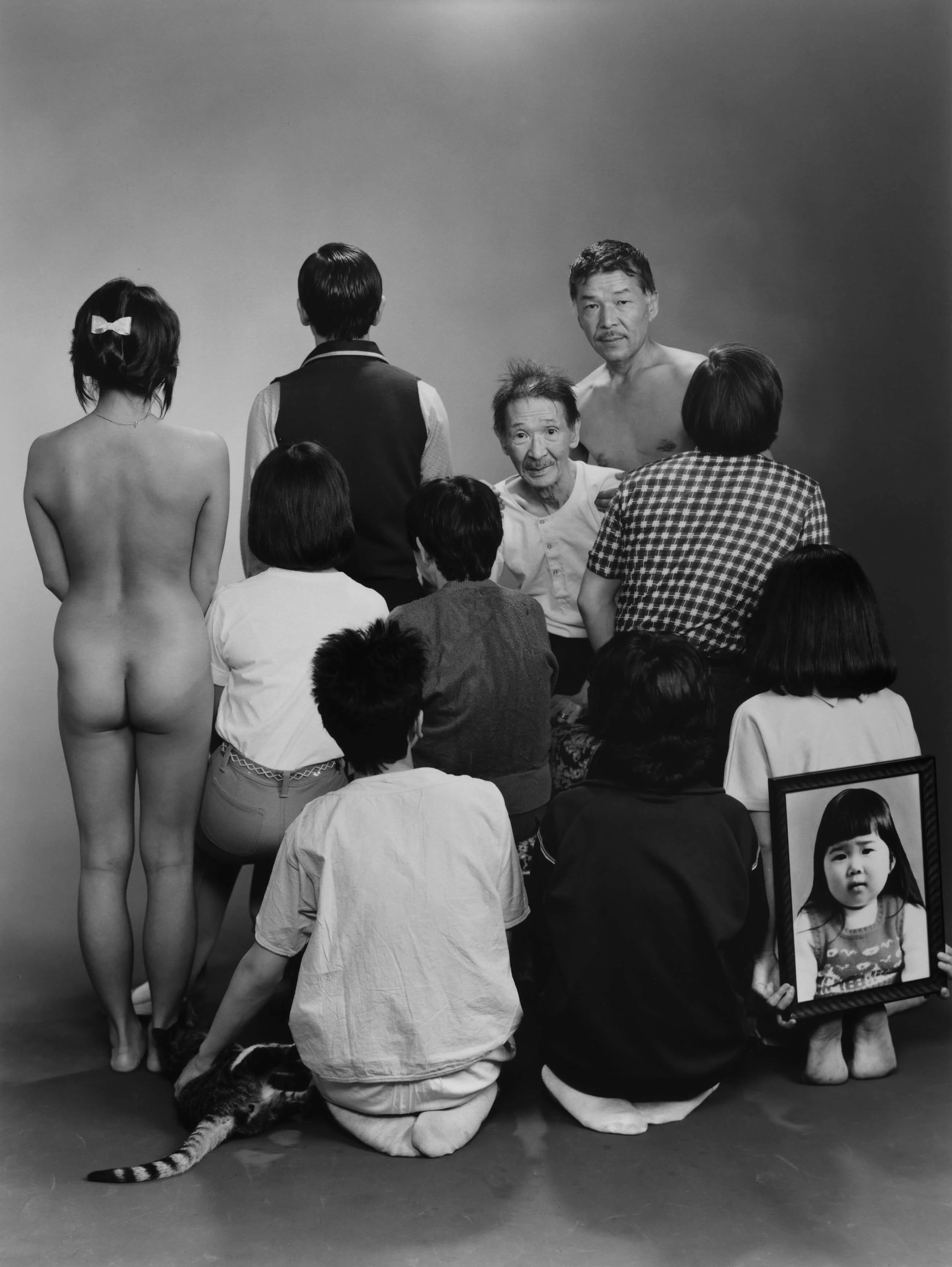

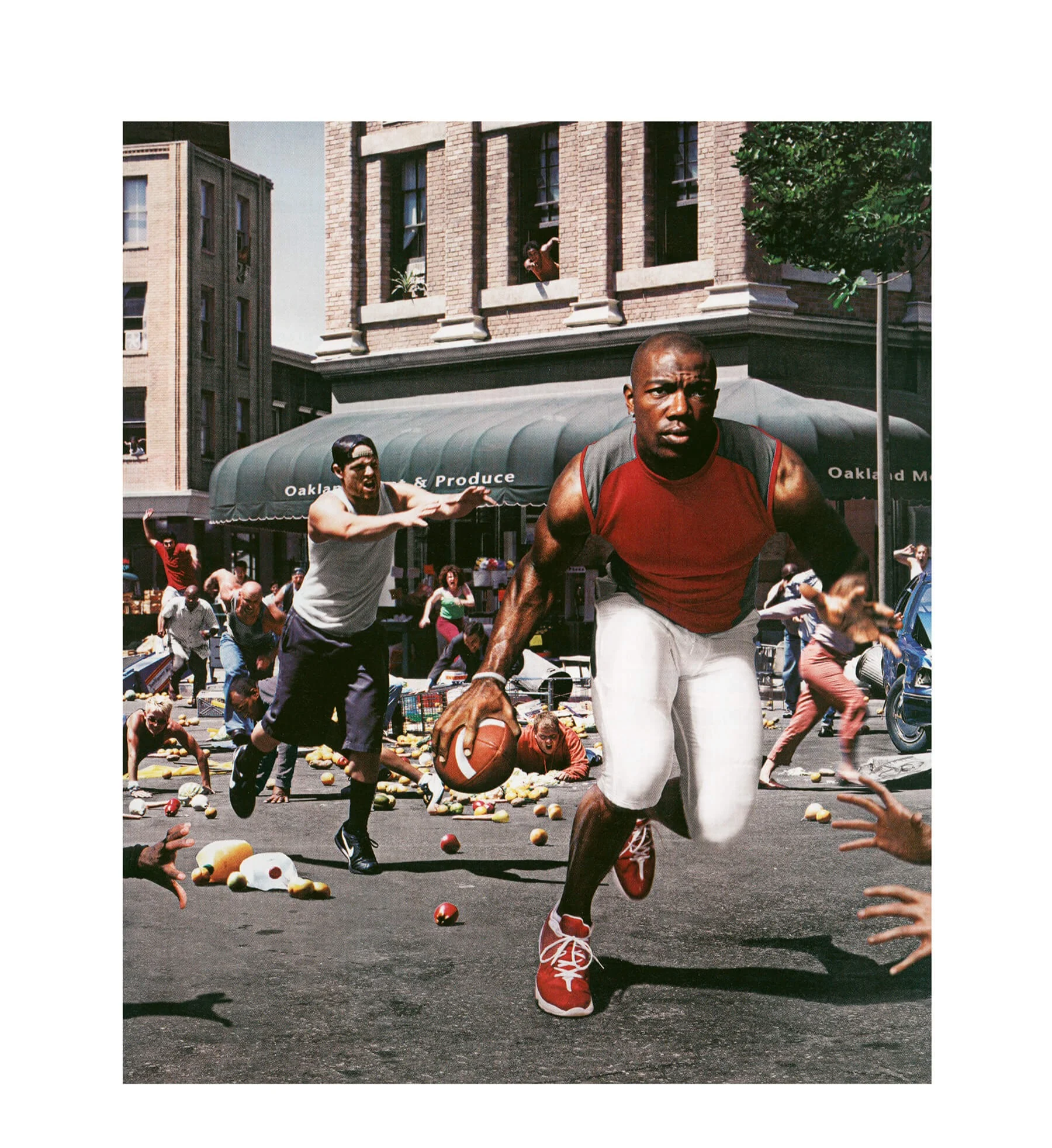

It’s this overwhelming archetype, and the many facets that are hidden beneath it, that are present in Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography – a new exhibition currently on show at London’s Barbican Art Gallery that dissects how imagemakers have portrayed masculinity throughout modern history. Note the use of plural; an inviting ambiguity, and a suggestion that the subject is far from straightforward. Instead, it can harbor many meanings simultaneously – none of them accurately adhering to the stereotype. In the exhibition, the “masculinities” on show are boundless. They are one gay man capturing another as he climaxes in front of the lens. They are a queer artist (Catherine Opie) documenting American football players (High School Football, 2012) – a figure synonymous with both triumph and toxicity. Or a woman (Annette Messager) zooming in on the crotches of men in the street (The Approaches, 1972), contemplating the trash or treasure that might lie beyond their trousers.

It would be convenient, if untrue, to suggest that the portrayal of masculinity as a proudly fragile and campy one is purely contemporary. As Hujar's work proves, men have toyed with the boundaries of gender for centuries through art. In the late 1800s, photographers started capturing the first wave of drag queens who’d entertain the masses at cabaret nights, like the Broadway star Julian Eltinge. A little later, photographers like George Platt Lynes captured queer men on England’s beaches as free spirits, almost pansy-like, in the 1930s. But the men from the mid-20th Century onwards have been framed by society as brute forces, and have largely adopted that outlook without question. The throughline of the work that unpacks masculinity in the modern age is that it knows this facade and sees straight through it. Instead of documenting a mirror image, photographers focus on the flecks of light that bounce back; a space in which the more interesting discussions lie. Ryker Allen, one of photography’s most talked about new purveyors of masculinity, finds those flecks fascinating. “As you dig deeper into the roles of masculinity, the skin sheds off and it becomes more apparent that the surface is nothing but a performance,” the non-binary photographer and producer says. “The root of why such a performance is presented, which I assume is a barrier men use to protect themselves from emotional vulnerability, is far more interesting to capture.”

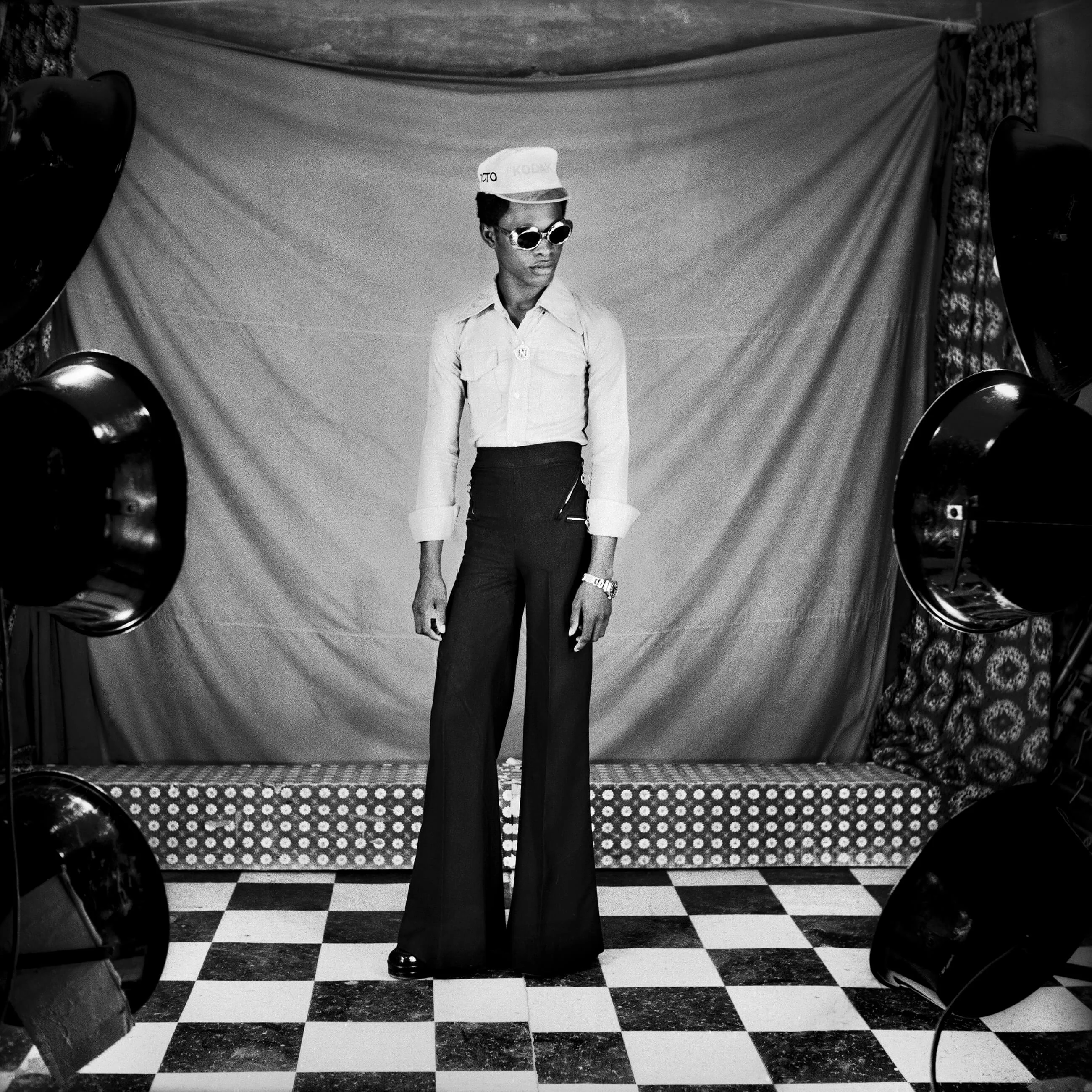

Take Soldiers, the series of images taken by Israeli photographer Adi Nes throughout the 1990s. The concepts of war and masculinity have been eternally intertwined, as if to swerve any chances of softness (littered with connotations of loss and surrender) being embedded into its make-up. Nes’ work draws criticism for its fragile, sometimes homoerotic subtext. Images of a bus of soldiers in slumber are shown alongside the same men wrestling in water over a gun, in a formation that could be mistaken for a dance. They’re staged, but in a way that feels documentary-like: hidden beneath the performance are photos that flirt with fact. Similarly, in Samuel Fosso’s work, portraits of glamorous men – some self portraits – were once covert rebellions aimed at Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the so-called Emperor of Central Africa who banned the wearing of tight clothes. Behind closed doors, Fosso created his own fantasy.

That notion of performance is key here. The most vitriolic aspects of masculinity – violence and domineering sexuality, for example – are performative traits that men have adopted and abused through years of systemic conditioning. “Masculinity has changed a lot in the West during the several millennia of our history,” Sherry Buckberrough, Professor Emeritus of Art History at Hartford Art School says. “Often art has shown men as warriors, actually or potentially violent. On the other hand, there have been lots of eras in which men have been seen as elegant, perhaps even beautiful. ‘Real’ men in the 18th Century wore lace.”

Catherine Opie is a master of picking apart that violence. In her aforementioned portraits of American football players, her lens permeates the idealised, deified image of an all-American sportsman and finds the real figure underneath. In some cases, she hypersexualizes them to the point of homoeroticism through crop tops and bulging biceps, or strips them down to unveil the reality: scrawny boys shielded by ostentatious costumes. In one of her earlier works, Being and Having (1991), she applied facial hair to 13 lesbian women, as if to highlight just how facile these projections of masculinity were. There is a constant requirement for men to be greater; Opie’s work both sympathizes with and ridicules that.

This ridiculing aspect is something that’s often exclusive to women artists portraying masculinity in their work; a subtle subversion of the oppression their gender has experienced at the hands of men through history. Behind a woman’s lens, men can be straightforward subjects (through unflattering, yet underseen portrayals of their very being) or deliciously objectified, given a taste of their own medicine. Tracey Moffat’s 1997 film Heaven is shot from the shadows of beach-side parking lots, as men in wetsuits strip down and change, exposing nude skin. Her lens ogles them. The same can be said for Annette Messager’s aforementioned series of calculated crotch portraits, shot from afar. It’s a welcome antidote to the abundance of scantily-clad women shot perversely by male photographers without question.

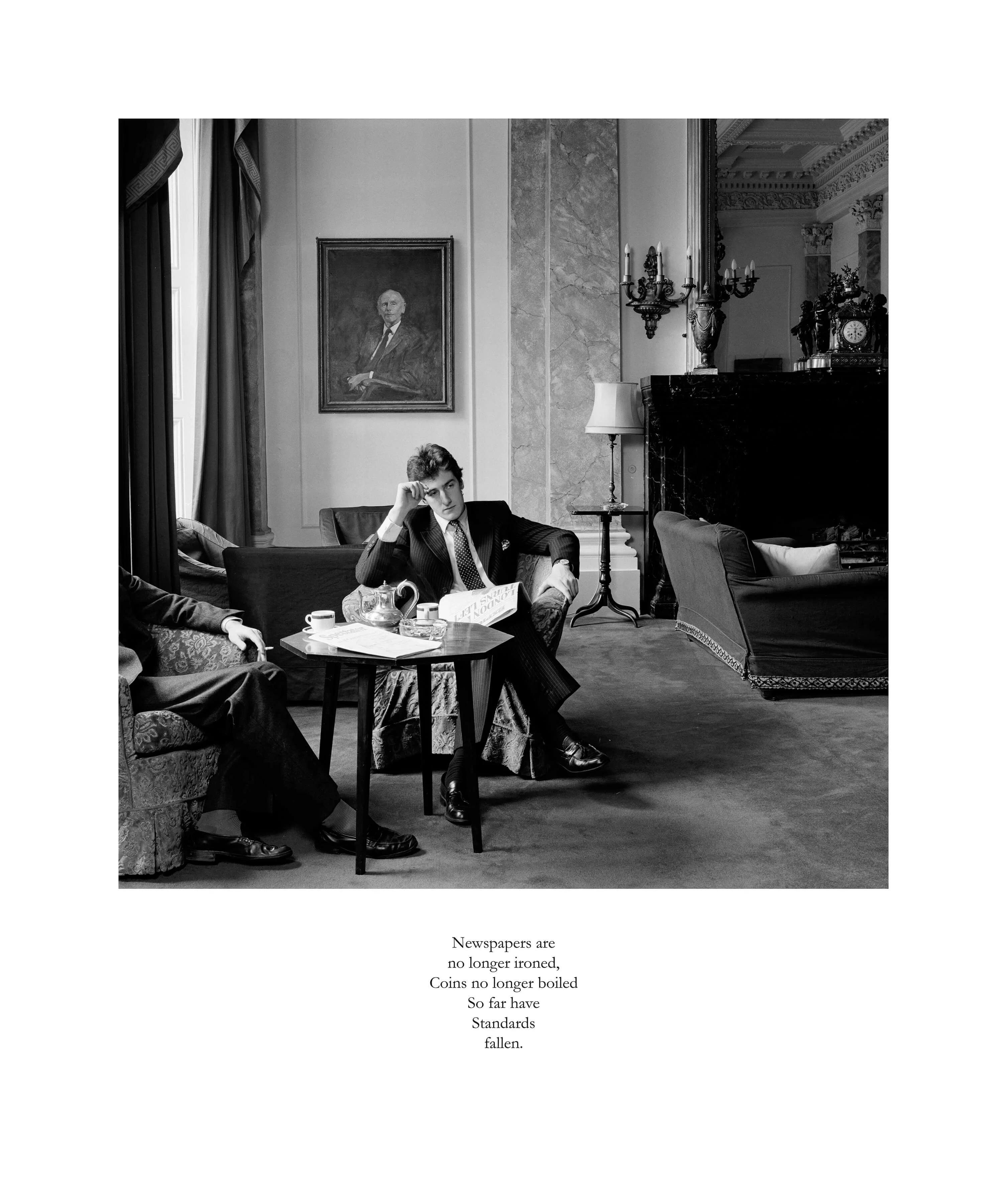

It’s worth highlighting that the performative aspect of masculinity can also breed hateful people, who chase unattainable expectations and claim victims in the process. Camaraderie often spills over into chauvinism, and when women enter the frame they are belittled. Andrew Moisey’s documentary series The American Fraternity captures masculinity in its most primal form, as college students drink, party and fuck their way through higher education. In his images, men in urine-stained boxers and fancy dress are juxtaposed with archival photos of past presidents from their college days. Portrayals of women are scarce, but blistering: shirts lifted with their face scratched out, or splayed across a bed with their legs slightly spread. It harbors a flagrancy that its earlier, more astute British predecessor, Karen Knorr’s Gentlemen, doesn’t. There, the near-empty rooms of London’s private member’s clubs seem to emanate the bigoted behaviour of the men who normally occupy them.

These breeding grounds for toxic masculinity have gained a sinister subtext in the #MeToo era. If anything, that long awaited removal of predators from creative power has lessened the demand for a handful of male photographers in the fashion space, particularly those who've been held to account for their actions: Terry Richardson, Mario Testino and Bruce Weber are a few who've been accused of sexual misconduct. These figures have struggled to have major work exhibited since these allegations came to light, and in their absence, the ones who've stepped forth have a far lighter, more optimistic outlook.

Those old-fashioned portrayals of masculinity and the toxic figures who help create them are slowly edging their way out in favour of a new way of thinking; their tropes twisted into something beautiful. While Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography graciously condenses a near-60-year period of masculinity into a stunning vignette, it doesn’t fully contemplate its future. That lies safely in the hands of a new generation of photographers, setting the precedent for new iterations of masculinity; one focussing on subverted notions of beauty, femme-ness and a further breaking down of the gender binary altogether. Tyler Mitchell, whose self-made success has since propelled him majorly into the fashion and culture sphere, is a master of lensing black brotherhood from an understanding perspective. Quil Lemons clamps down hard on hypermasculinity, reframing the cuts and bruises on rough-and-tumble boys’ faces with glitter in his work instead. And Ryker too: “Masculinity is far healthier and more visually intriguing when approached fluidly,” they insist. “I’m not really sure men even exist.” They are our new pioneers, starting the next chapter in a photographic tale that will unfurl throughout the century. The 2020s belong to them; and through their camera lens, masculinity will always be malleable.