A series documenting the rise of Sumo wrestling in Mongolia

Sumo wrestling might be the most Japanese thing you can think of. But in Mongolia, there’s a thriving, competitive subculture embracing and perfecting the much-misunderstood sport. Catherine Hyland went to document The Rise of the Mongolians.

Interview by Lucy Pike and Alix-Rose Cowie.

In a sumo wrestling club in Ulaanbaatar, Catherine Hyland is stuck. The British photographer has spent months planning this unusual and challenging shoot but now, in the Mongolian capital, something isn't working.

She wanted pride. She wanted personality, and energy. But her subjects, all adult fighters, stand around timid and stilted. Everything she says must go through her translator – 45-year-old local Batbileg Sukhbaatar – and the energy is all off.

“What they’re feeling becomes a mystery. You can't communicate to say – I'm a nice person and I want to make you look good! So that whole thing is totally cut off. Who knows what we would have made if we were able to have a laugh together.”

But let’s rewind. What led to this moment, to Catherine tearing her hair out in a sweaty sumo club in Ulaanbaatar?

For centuries, sumo wrestling was an insular sport, preciously protected by the Japanese Sumo Association (JSA) - the only professional sumo organization in the world. But somehow, over the past 25 years, a group of gaijin, or foreigners, from Mongolia have come to dominate the sumo ring.

Wrestling has been part of Mongolian culture for centuries, and their style easily adapts to the sumo ring. Sumo's popularity has grown hugely, driven in part by the money and the glory which comes if you reach yokozuna status – a grand champion in the ring.

The first Mongolian sumo champion was Dolgorsürengiin Dagvadorj who won the Japanese title in 2003. Better known by his sumo name, Asashōryū Akinori, he’s been inspiring a steady flow of young Mongolians hoping to follow in his footsteps.

That same year though, the JSA ruled that sumo stables in Japan should be limited to just one foreign athlete per school. When the stables began to encourage foreign wrestlers to seek Japanese citizenship, the organization changed its rules again, limiting access to anyone not born in Japan .

Catherine first heard about the Mongolian sumos (and the Japanese attempts to keep them out) when she was in the country shooting her 2017 project, Universal Experience. She knew it would make an interesting series and was intrigued by the tension between the Mongolians' talents and the challenges they faced breaking into the sport.

“I’ve gotten more and more interested in this idea of abuse of power,” she says. “The more I read about it, the more it seemed apparent the Japanese had tried to use red tape to keep the Mongolians out of sumo.

“When you show certain capabilities and you intimidate people – in all walks of life – they'll try and keep you down. I called the work The Rise of the Mongolians because they're 100% the underdog of the sport. But their natural ability now means they can't be ignored.”

Planning the project from her home in London wasn’t easy. Whereas she’s used to working independently, just her and her camera, she now had to rely on fixers and translators to put her in contact with her subjects.

And once she was there, things didn't get much easier. It took many shoots, with many subjects at many locations to get the images she was happy with. As often happens, the turning point came as a flash of inspiration.

What if she took some of the younger fighters out of the club, out of the city even?

Getting out of Ulaanbaatar immediately opened up new possibilities. “Ideally, you don't really want to be doing things impulsively," Catherine says. “But at the same time I think that's when some of the best work gets made. When we were trying to get the older sumos together in the gym, it was actually very stale compared to the rest of the work we made.”

Catherine remembered a village she'd been to on her previous trip in the Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, a two-hour drive from the capital. Most of the boys had never been there.

Their worlds were focussed on Ulaanbaatar, where nearly half of the entire Mongolian population lives. It's a tough place to grow up; a poor, crowded and polluted city. Many families were forced to move there in search of work, after a series of brutal winters destroyed traditional rural communties and the herds they kept.

“I think it was lovely to get them out of that atmosphere,” Catherine says. “You get this surreal hotchpotch of new skyscrapers and decaying Soviet tower blocks surrounded by thousands and thousands of gers and yurts. It’s an extremely overwhelming sight.”

Catherine was aware of the dangers of picturing the young sumo wrestlers in a stereotypical way. For her, the village was a good middle ground between shooting in the polluted city, and taking the boys out into the empty Mongolian plains – a visual trope which has been done before.

“I think we see a lot of things in Mongolia where people go and plunk someone in the most desolate location, because that's what we expect of Mongolia," she says. "I didn't want to do that. We've seen the nomadic element of Mongolia – we know about eagle hunters and these last tribes that live there. I wanted to show this more lively and, in a way, warmer side to Mongolia.”

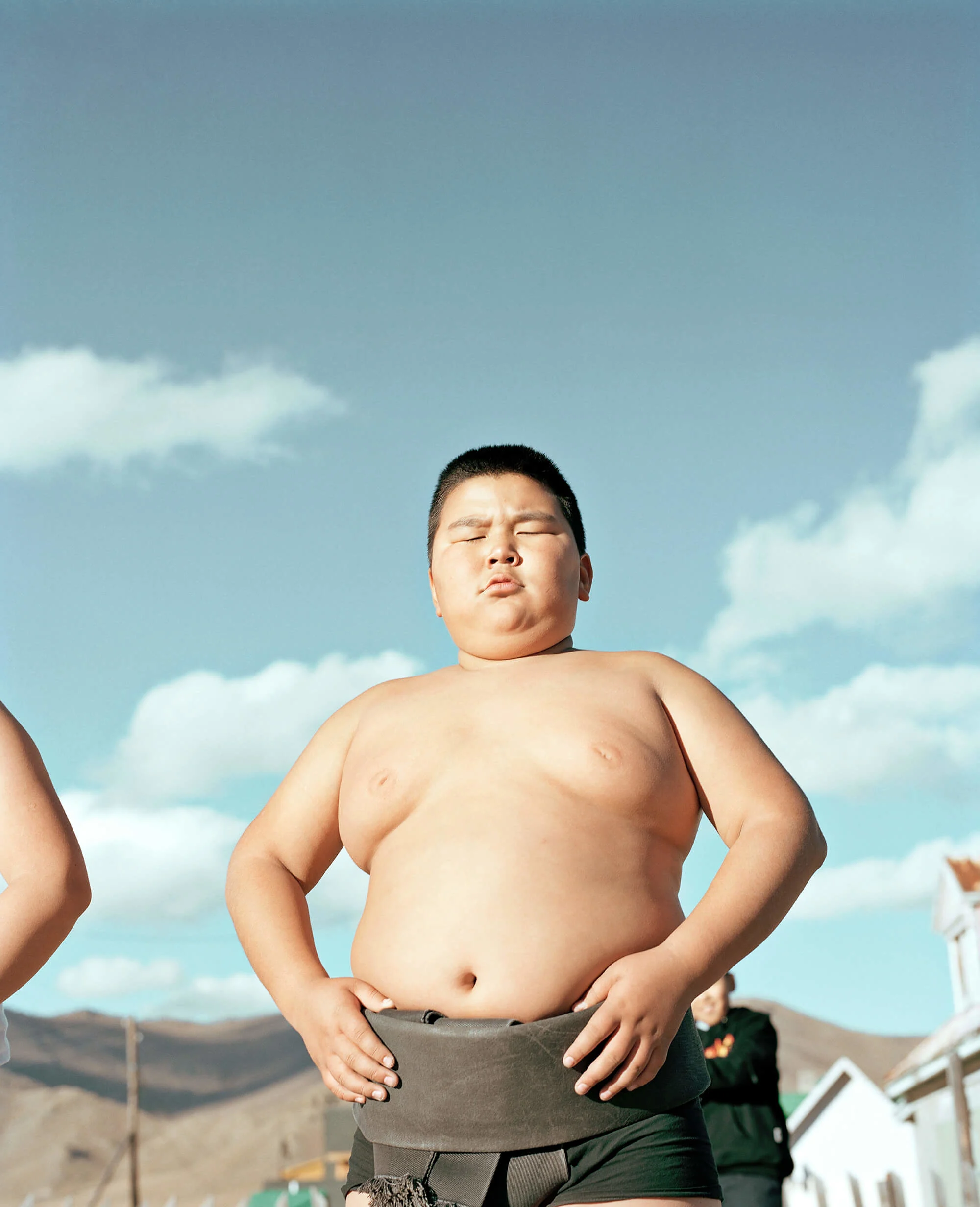

Dressed in their sumo belts (mawashi) the boys postured, played and puffed their chests out for the camera. The pride and personality that was lacking in the earlier shoots now bursting out of the images as they faced off against each other in the ring, or posed for portraits.

I wanted to show this more lively and, in a way, warm side to Mongolia

It helped that the boys know each other well from the hours of training together at their sports center. “I think they've got amazing camaraderie,” Catherine says.

Their different personalities clearly shine through too – some more confident and aggressive, others cheekier and more playful. "Even in the car we were having a chat and having fun. It was so different to working with the adults who seemed very nervous and vulnerable.

“This is supposed to be something to be celebrated. That’s what I wanted people to see rather than it being about poverty or hardship.”

When shooting, Catherine lets things play out as naturally as possible. “I'm always trying to not control the situation because I’m genuinely interested in people’s natural personalities and what they want to express,” she says.

“It's only when things aren't working that I'll try and step in and be a bit more pushy. But if I can avoid that, I will. And that was actually great in this respect because the kids, they just kind of created this whole narrative themselves.”

They just kind of created this whole narrative themselves.

Catherine’s sunny images capture a lot of different things. There's the determination of the boys, their companionship, their hopes for a better future if they can become professional fighters. But they’re also a portrait of boyhood; kids being kids.

She thinks you can look at a city like Ulaanbaatar in different ways. You can focus on the problems, the hardship and the poverty. "Or you can look at the optimism of the people that live there," she says. "I always want my work to have optimism embedded in it.”