When she felt torn between fine art and photography, Alina Frieske found a way to paint with photographs. Taking hundreds of small fragments of found images, she gradually pieces them together to create her own unique scenes. Her work explores how we relate to and understand images, and how with enough vague perspectives we can create a clear picture of what’s really happening.

Written by Alex Kahl.

As German photographer Alina Frieske was coming to the end of her degree in Visual Communication, she wrote a thesis exploring how we understand images and how we classify them, including a section about image recognition technology. Back then, she would visit natural history museums regularly, and on one visit decided to take images of some of the exhibits and put them into Google’s reverse image search. She used small pieces of the photos the search brought up to recreate the original ones she had taken. “That was the moment I started working with data collection and existing images and creating my own original image out of them,” she says. “I used fragments of found images and pieced them together to create something new.”

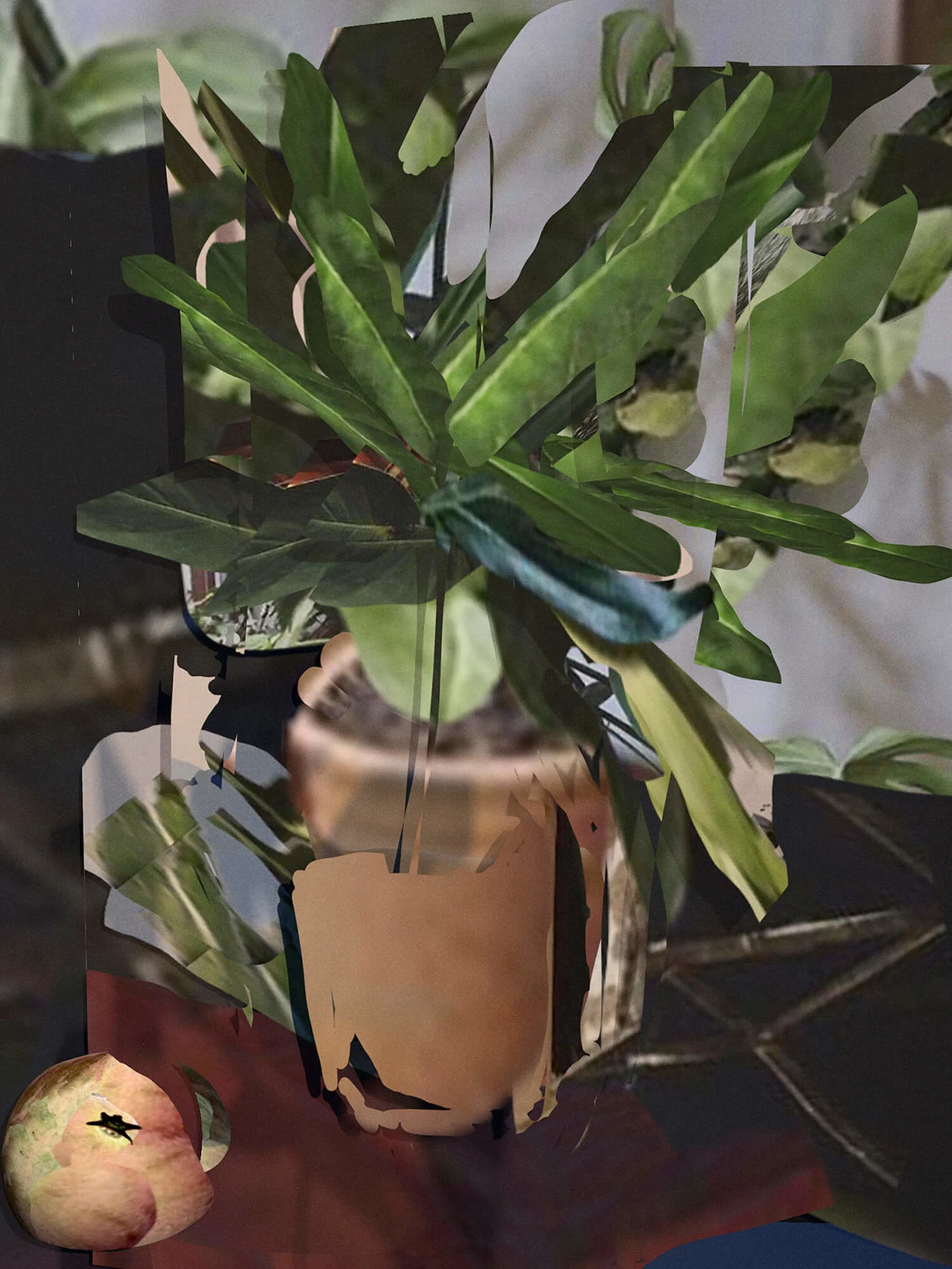

Alina’s process always begins with drawing the outline of the image she wants to create, and she then fills in this outline using the fragments she finds. “I have this folder of material where I look for a specific color structure that could represent the various details I need to depict,” she says. “Most of the time I just take a snippet of that image, and fill the outlines of the sketch that I’m doing. And then it builds up for quite a while. It’s a very long process of gradually building the image.” These first works became Imagined Recordings, a series made up of her own interpretation of the animals she’d seen at the museums.

Alina had always been more interested in fine art, and especially painting, but she had also long admired the immediacy of photography, the way it could capture whatever was in front of her at an exact moment. “This technique was an attempt to keep this interest I had in painting, and to find a way to paint with photographs.

Up close, you see the truth. You see the remains, what it was before.

Using them as brushes or marks, placing them on top of one another,” she says. She found similarities between the pixelated photos that came up in the image search and the classic paintings she loved. “It’s about the resolution. My final piece is very much based on the digital image,” she says. “There’s something very painterly in the structure of a pixelated photo.”

The results of this series convinced Alina she wanted to continue on the photography path, and she began to study for a Masters in Photography at the University of Art and Design in Lausanne.

From afar these works might look like paintings but up close, because of their “collage” element, every small section of each piece can be seen as its own small work of art. Alina sees this as a performative aspect of her work. “It’s about perspective. From afar you might get a certain feeling. Up close, you see the truth. You see the remains, what it was before,” she says. These ideas of shifting perspectives play a huge part in Alina’s work and its subject matter, and this was especially true in her most recent project, Abglanz.

Before starting on the series, she became interested in online exposure, and the ways we represent ourselves in our online personalities. She was especially curious about the idea of public versus private: what people will and will not share with the world.

How many vague perceptions of a moment can we bring together to create something substantial?

The theme of repetition online also sparked her interest. Think about the galleries of selfies people post on their social media profile. Often you’ll see three consecutive photos, each one with only a miniscule difference to the next. You’re seeing three images, but you’re receiving no more information than you would have done with one image.

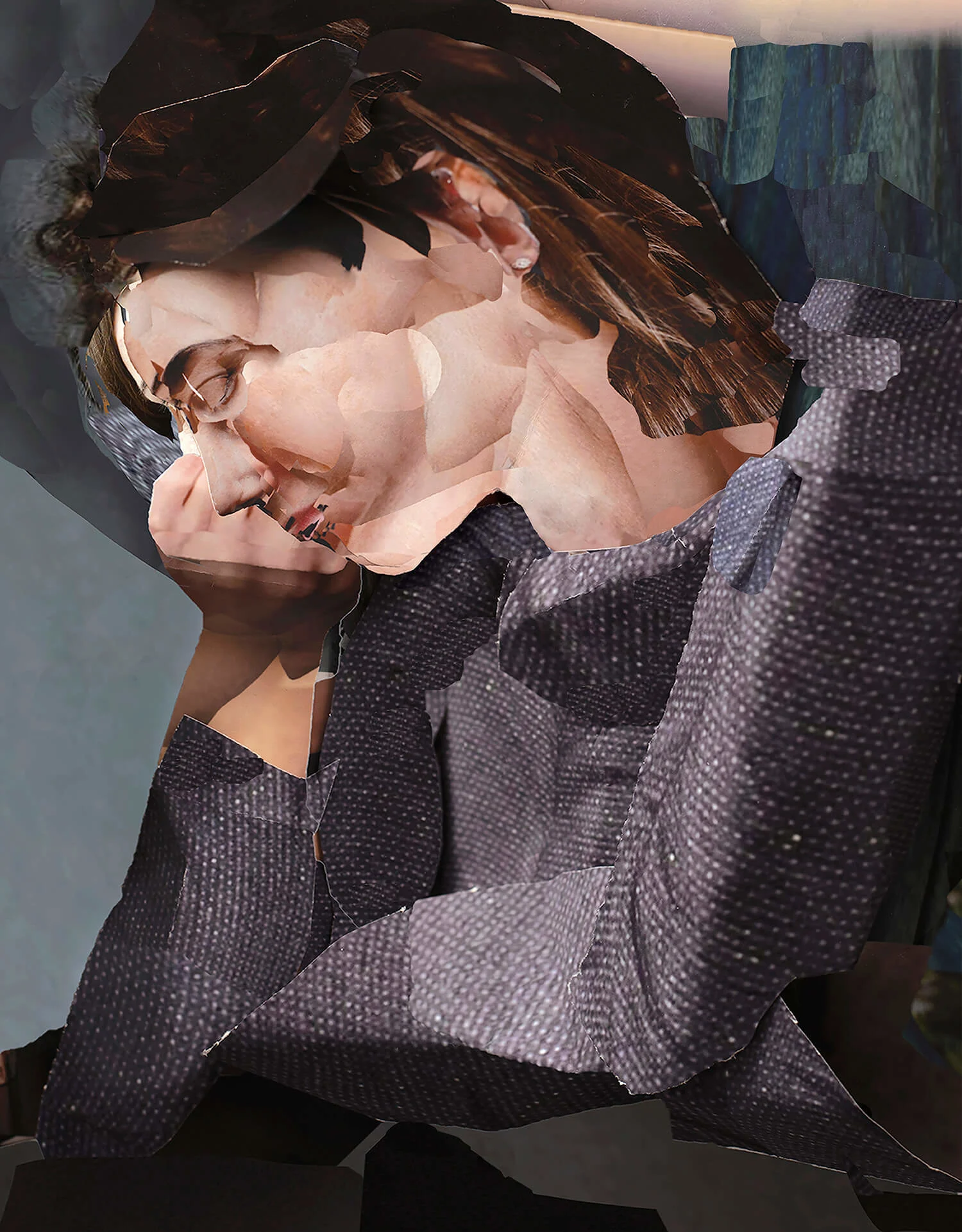

These were the thoughts on Alina’s mind when she started work on Abglanz, in which each image shows a different angle of the same room at the same moment. In one image we see a woman in a black top sitting at a kitchen table, and the shoulder of the woman in red sat next to her. Another image shows the women in red in her entirety, but in the reflection of a mirror on the other side of a room.

Each image, on its own, is vague, but when you view them as a series, you’re able to create an idea of the moment as a whole. Despite viewing it from all these distant angles, there’s still some mystery in the scene, with shadows cast over different surfaces.

The question Alina asks is: “How many vague perceptions of a moment can we bring together to create something substantial?” Even with the almost identical Instagram selfies mentioned previously, over a longer period of time the selfies might provide enough slight changes in perspective to get an idea of the person’s entire life.

It’s that stillness and that moment of reflection that inspires me.

Just as Alina pieces together tiny fragments of images to create something new, we can take small perspectives of a situation to see the overall picture. “I was inspired by the fact that with so much material existing online, you can quite easily create a 360-degree view of any situation,” Alina explains. “Because every detail can be found somehow, so it’s just about piecing all of those together.”

The project’s German title translates to “reflection,” and Alina wanted reflective surfaces to be a big part of it. “It’s this idea of a distant echo, the way repetition makes something weaker in a way. Like those mirror selfies,” she says. A theme Alina explores in Abglanz is memories, another thing that a photo can represent and which also usually become weaker as they are repeated and as time moves on.

Looking at the series can make you feel like a passive spectator in this calm moment in a quiet living room. Viewing all the pieces together, you start to feel the atmosphere in the room. The wistful looks out the window, the photo frames on the dresser, and the color scheme of deep reds and browns gives a real sense of nostalgia and the passage of time.

This scene is a moment from the past, and the different perspectives and angles onto the scene are a reminder that everyone’s memories are unique, and that one moment can appear different to everyone. It’s an uneventful scene, but quite often the things that stick out most in your memory are those idle minutes where nothing notable happens at all. “There’s this stillness and this moment of reflection that inspires me,” Alina says. “It’s not a specific moment in time. It has this strange floating feeling to it. It’s timeless.”