In Sitka, Alaska, musician and artist Nicholas Galanin creates music as Ya Tseen. Imbued in his new record, and across all of his creative output, is a conscious effort to shift the narrative away from painful histories of Indigenous peoples. Kate Hutchinson meets the fascinating artist whose work seeks to humanize Indigenous experience in the world.

Photos by Vivien Kim.

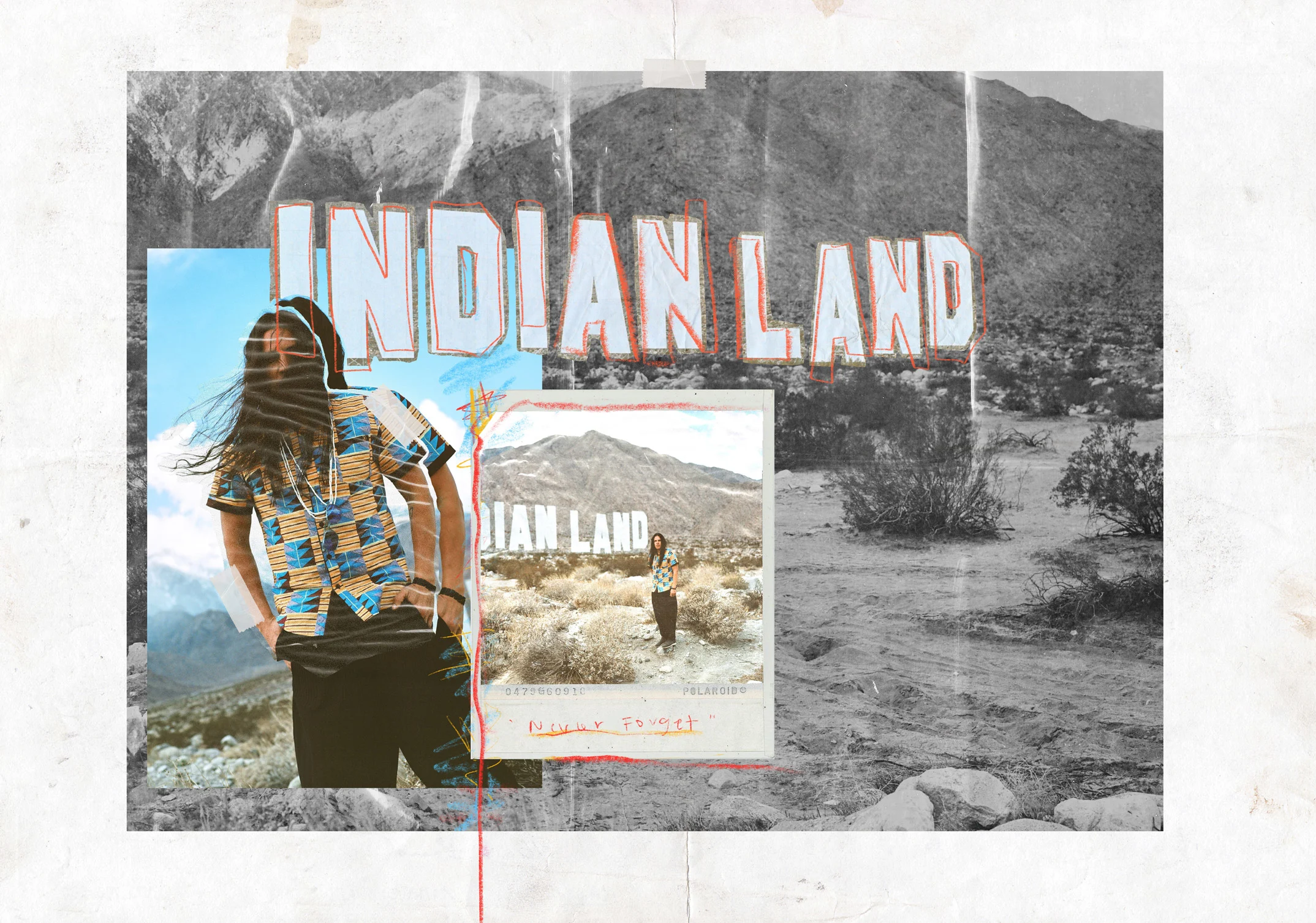

If you’d been traveling through the pale and parched desert of the Coachella Valley, California, this past month, you might have done a double take. Standing 45ft high, rising out of the chalky rocks and cholla, near the popular holiday destination of Palm Springs, stands a familiar looking sign. It displays one of the most famous typefaces in the world, featured on countless guidebook covers and selfie backgrounds, one that is synonymous with stardom and the American Dream. But instead of spelling “Hollywood,” this sign spells “Indian Land.” It’s a site-specific work created by 41-year-old artist/musician Nicholas Galanin, a showy reminder that the playgrounds of the rich and white are on stolen land, and a rallying cry to return what isn’t theirs.

The misrepresentations upheld by institutions transfer into the mistreatment of our communities still today.

“That iconic sign was historically placed as a white-only real estate advertisement. A lot of people don’t know that,” Nicholas says of the Los Angeles landmark, which was erected on the Hollywood Hills in 1923 and at first spelled “Hollywoodland.” The message behind the sign aligned, he continues, with “manifest destiny” – the belief in the 19th Century that white settlers were divinely ordained to colonize the US – and consequently “the displacement of Indigenous communities from their lands and homes.” But it also speaks to the role that the film industry has played in perpetuating “a certain version of Indigenous communities,” he says, “not portraying us as we, portraying us as a stereotype. The misrepresentations upheld by institutions transfer into the mistreatment of our communities still today.”

Nicholas’ piece, which is titled Never Forget, is a standout work at this year’s Desert X festival, cementing him as a crucial voice in contemporary art. His use of the word “Indian” has sparked some concern within the community on whose land the sign stands – the Agua Caliente reservation, belonging to the Cahuilla tribe – who feared it was reductive but Nicholas, who is both Tlingít and Unangax̂, says it’s a knowing reference to a word he disagrees with. “‘Indian’ is a monolithic term that was embraced by the government as it removed each individual community from their place and space,” he explains, even as it describes “over 560 Indigenous communities, with unique cultures, unique histories.”

These types of messages skewer much of Nicholas’ work as a multi-disciplinary artist who defies easy categorization. His work spans sculpture, performance art, textiles, photography and installation, and pulls no punches. Take, for example, his disturbing taxidermy polar bear and wolves, their hindlegs flattened into a rug in a struggle for survival, or the grave he dug for the statue of Captain James Cook during last year’s Sydney Biennale, as busts of colonizers were being torn down around the world. Another recent piece, Land Swipe, featured the NYC subway map painted on a deer hide and marked with various sites of police brutality against Black youth. Every piece feels like baring teeth, speaking undeniable truths.

In another left turn, however, he’s also about to release a new album on Sub Pop as Ya Tseen. It is a widescreen epic of joyous, synth-driven indie-pop, electro-soul and borderless beats. Both that record and Never Forget took three years to come to fruition, both are bringing him to new audiences and both underline an artist who refuses to be hemmed in.

At home, in Sitka, Alaska, a picturesque town that faces the Pacific Ocean, Nicholas hasn’t had much time to take stock: he is currently campaigning to protect the local herring from overfishing with his children and building an enormous 23ft canoe intended for cultural use. He’s from a family of artists – his father, David Galanin, taught him guitar and metalwork, and his great-grandfather was a wood carver, as is his uncle. This dugout, Nicholas says, is the most technically difficult to make. They’re not just incredible pieces of art but they have to float and “keep communities safe.”

Despite this clear link with ancient practices, he prefers to avoid connotations that root his work and heritage in the past, or that fetishize the “authenticity” of Indigenous cultures. Nicholas sees his work as part of a “continuum” instead, with the binary between tradition and contemporaneity blurred. “The foundation of a lot of the work that I do is here, where I come from, and my culture,” he says – but that’s not to say that his work isn’t cutting-edge. He works freely across mediums to avoid lazy labels and presumptions. “Oftentimes those ideas of authenticity are based on these romantic perspectives that don't see us as now,” he says. “The work we do now can be anything. It doesn't have to be a carved totem. It doesn't end there.”

Nicholas’ career has long entwined art with music. He studied fine art, jewellery design and silversmithing at London’s Guildhall University in the early 2000s, performing his first open-mic night in the capital while a student, and went on to receive a Master's in Fine Arts in Indigenous visual arts at Massey University in New Zealand. A few years later, in 2011, he released an album called Digital Indigenous, in which he rapped over booty bass rhythms, and then switched it up for alt-folk music between 2012 and 2016 as Silver Jackson, on his own label, HomeSkillet (the same name as the festival he ran in Sitka for 10 years).

Ya Tseen is a conscious effort to shift the narrative away from painful histories – liberation as an act of resistance.

Indian Agent, a trio with Silver Jackson bandmates Otis Calvin III and Zak D. Wass followed, referencing the untapped history of the “Indian agents”, whose job it was to violently keep Indigenous population in line during the 1800s. Their lacerating 2017 album of hip-hop and experimental electronics, Meditations In The Key Of Red, arrived around the same time as the protests against the Dakota Access pipeline became spotlighted Indigenous rights and climate change activism worldwide (they had a song called Dakota on the record). He laughs at the suggestion of whether he ever has an identity crisis – art enfant terrible or rock star? – and says simply: “I don’t separate the two.”

While his visual art presents serious messages for serious times, and he talks seriously about them, there’s a swooning effervescence to his new music as Ya Tseen. It translates as “be alive” and the album, Indian Yard, radiates warmth – untethered to genre but recalling, in places, artists and groups like Animal Collective, TV on the Radio, Moses Sumney and James Blake who recast unstarry sounds with an intimate glow. He has teamed once more with Calvin III and Wass, as well as gathering a raft of collaborators between Sitka and Seattle (home of Sub Pop). They include Shabazz Palaces, Erik Blood and Stas THEE Boss – with whom Galanin forms part of the Black Constellation art collective – as well as Alaskan rockers Portugal. The Man and Qacung of “Inuit soul” band Pamyua, who sings on the closing track in his native Yup’ik.

Indian Agent was direct and specific in its intention but Ya Tseen is a conscious effort to shift the narrative away from painful histories – liberation as an act of resistance. It’s a more nuanced exploration too, perhaps, of how the personal intersects the political than some of his more direct visual artworks: there are sublimely catchy songs about the intricacies of love and finding your feet in new relationships, desire across the distances, birth and parenthood, love, loss and longing for connection – universal themes, told from an Indigenous perspective.

“This album humanizes Indigenous experience in the world in a society that has historically dehumanized us,” says Nicholas. “It doesn't abandon the battles or the things that we still work daily towards in our communities, but I feel like it creates space for conversations based on all of these other aspects that oftentimes are overlooked intentionally when we're written about in the institutional or academic world. We have love, we have joy, we have our families and our children. We're not only defined by trauma; we're not only defined by these aspects of our history. You can't always get that through one art project.”

This album humanizes Indigenous experience in the world, in a society that has historically dehumanized us.

Not one to submit to the cliché of a happy ending or a clear resolution, Indian Yard grows gradually more ominous in tone: one of the most intriguing tracks, the Sun Ra-referencing Gently To The Sun, imagines a space above the Earth without police brutality, pre-colonization, and with a poem rapped by Tay Sean atop a syncopated beat – Nicholas’ take on Afrofuturism, perhaps, where post-punk meets rap meets jazz. “I love where you can go sonically if you let yourself move those ways,” he says. Synthetic Gods, meanwhile, featuring Palaces and Boss, includes audio footage from the protests on Seattle’s Capitol Hill last year during the Black Lives Matter uprisings during its taunting trap abstractions. And it ends with Back In That Time – mercuried rap with menace.

The possibility of the future is an important aspect of Nicholas’s work; he’s not just critiquing the present. His two-year-old son, At Tugáni, appears on Indian Yard’s cover, wearing a sweetgrass-woven VR headset made by his’s partner, Merritt Johnson, based on a photo series that she did called Mindset. They reshot it for the album to teasingly nod to baby covers such as Nirvana’s Nevermind, a Sub Pop classic, as well as imagining an approaching utopia that is knotted with the past. He reads from the piece’s mission statement, as if an episode of Black Mirror: “The sweetgrass headset offers temporary disconnection from toxic cultural surroundings for envisioning good ways to create and contribute to present and future realities.”

We could all do with some more of that energy in 2021. Nicholas notes that Indigenous representation is changing – see, for example, the number of young people celebrating their tribal heritage on TikTok, with challenges like “So What Native Are You?” – and that youth embracing their culture “is a big shift away from abandoning or trying to escape something,” referencing a not-too-distant time when native peoples were encouraged, or forced, to assimilate. He says that his daughter in Sitka is “taking Tlingit language class in middle school. I was in middle school here for a little bit and they didn't teach anything about our culture. Reclamations and resilience of our culture in these times is testimony to the strength of our communities.”

We have love, we have joy, we have our families and our children. We’re not only defined by trauma.

But that change is “never fast enough,” he adds. It’s why he launched a GoFundMe campaign alongside the erection of his Desert X installation, encouraging participants to contribute to the Landback Movement, which raises funds to acquire legal title to Native American homelands for Indigenous tribal communities. “Never Forget is a call for more direct action towards those changes,” he says, “and a very literal way of saying ‘here, this is one form of engagement that you can participate in.’ That's the actual piece. The work is not the monument, the work is the action.”

For him, art has always come hand-in-hand with activism – but shouldn’t we all have the same version of that? “I have a responsibility to my children and their children. We all do,” he says. “That's what you may call activism but I think it's realizing and utilizing your tools to engage your responsibility. I can create other aspects that engage joy or love or abstraction. But the reality is that some of these things are just really important.”