Each one of South African artist WonderBuhle’s portraits is imbued with flowers that fill their backdrops and cover his subjects’ bodies. The plant in question, the impepho, is used widely in his community, both medicinally and as a means to communicate with ancestors. He tells writer Katie de Klee about how his work is inspired by the history, traditions, and familial connections that defined his early life growing up in rural KwaZulu Natal.

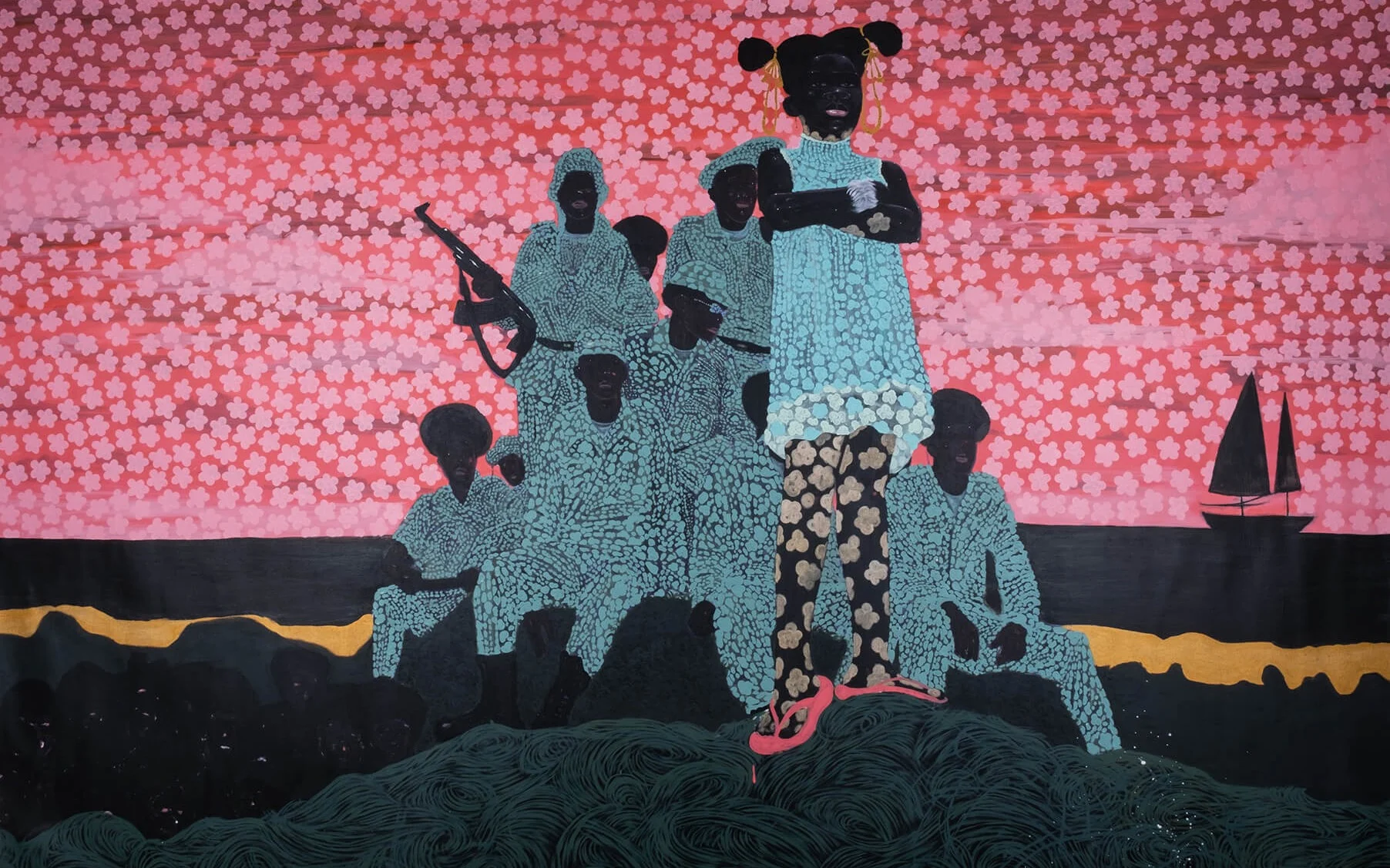

In South African artist WonderBuhle's large-scale portraits, dignified characters calmly stare out from their canvases, their skin covered by a veil of golden flowers. He uses these flowers to try and heal the trauma and violence experienced by the Black community in his country’s recent history.

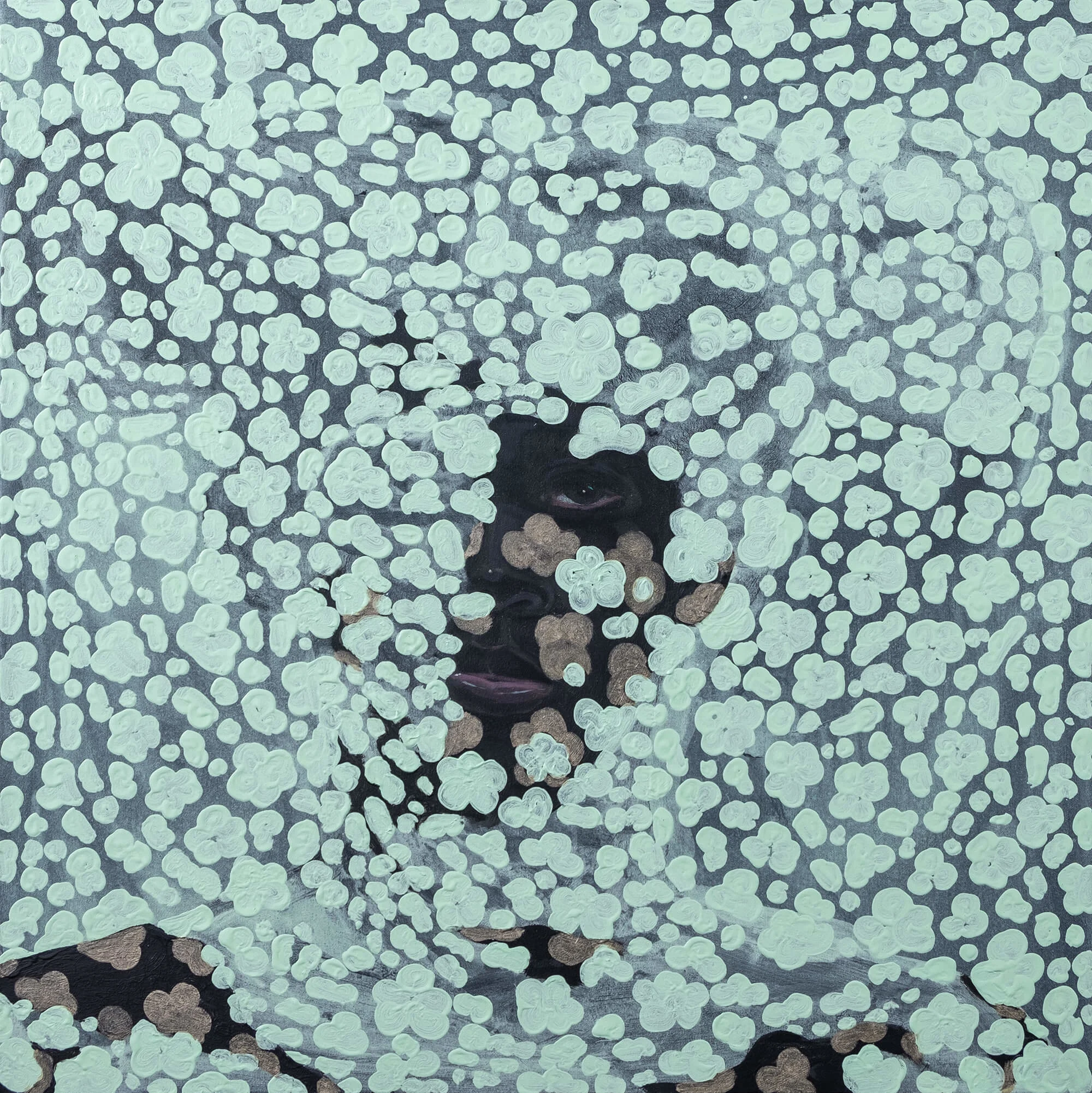

Wonder has been drawing since 2010 and painting since 2018, but his current visual language only emerged in 2018 when he first began to use this flower motif. The symbol comes from memories of a childhood spent in the village of Kwa-Ngcolosi in rural KwaZulu Natal. There, the plant impepho, which has small white or yellow star-shaped flowers, is used in traditional ceremonies and as a medicinal plant.

“I started to develop symbolism in my work with these flowers,” says Wonder. “There is so much generational trauma that’s been passed on in this country, and I needed to find an element I could use in my work to reverse that. Now I have something that defines me as an artist, something that’s taken from my home, my family, something that gives my work a feeling of belonging.”

The herb is primarily used in Zulu culture as a means to communicate with ancestors and invite them into a space. It's also used to cleanse a space when one feels there are bad spirits occupying it, or even to cleanse one's own body. The use of the impepho flower in his work is testament to how deeply connected Wonder is to his heritage and to ancestral wisdom.

When I paint I borrow a lot from my subconscious mind and from my early memories.

Wonder grew up in the care of his mother and grandmother, both of whom were matriarchs in his village. “My mother is a traditional healer; she’s known amongst the community. She does a lot of work with herbs and is a very spiritual person,” he explains. “She sometimes tells fortunes for people, and she helps them interpret the messages in their dreams. I took a lot from her.”

Some of Wonder’s works are inspired by his mother’s healing work. “She would dip her hands in herbs of different colors to rid herself of the city energy before doing any traditional ceremonies. The pink hands that have surrounded my work draw to maternal strength and the care that can surround us,” he explains. “When I paint I borrow a lot from my subconscious mind and from these early memories.”

While Wonder’s mother went to the city to earn a living, he would spend the days with his grandmother, and she’d tell him old stories that now re-emerge in surreal symbols in his paintings. In one work, for example, two boys hold a snake above their heads. Each of them has just one eye in the center of their foreheads and neither has a mouth. “I was told if you see a white python in the house, do not chase it away. And don’t tell anyone that you saw it. It’s a sign that fortune will follow you,” says Wonder.

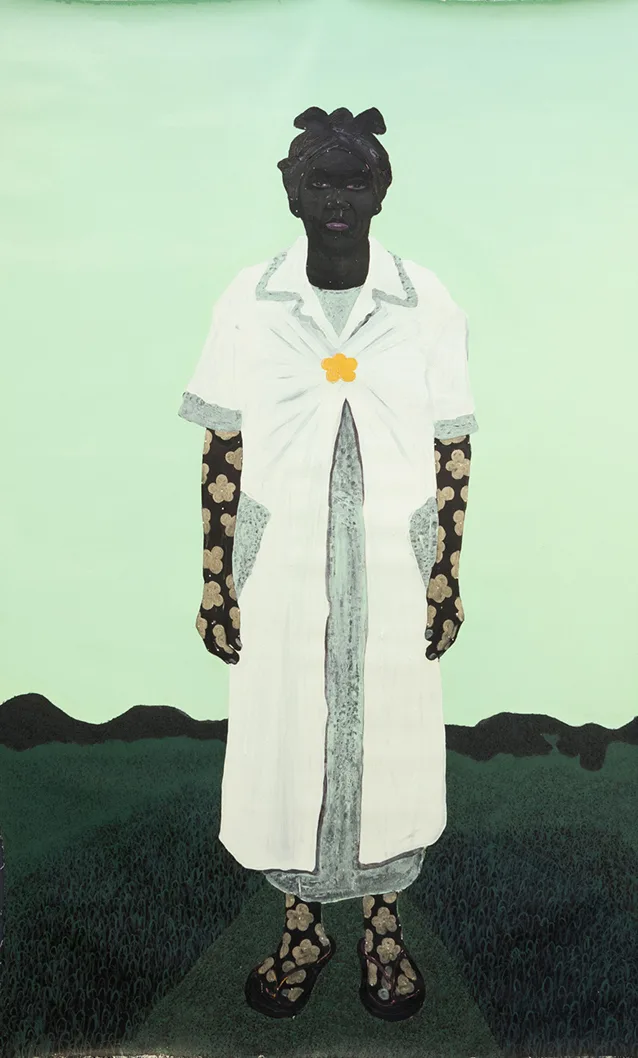

His grandmother’s portrait, “iSbonakaliso,” is one of the anchor pieces in Wonder’s latest body of work, titled uNyezi, the Zulu word for the moon or “the one who sits among the stars.” “‘iSbonakaliso’ is very important and very personal,” says Wonder. “My younger brother and cousins didn’t get the chance to spend time with my grandmother like I did. She taught me all about life, how to look at the world and how to act as a man. Now it falls to me to hand on ancestral knowledge. I wish I could teach them the way my grandmother taught me. I started to create this piece to represent her coming back to give them what I couldn’t give them.”

I want any Black child in the world to walk into any gallery or museum and see themselves on the wall as a King or a Queen.

Through his paintings, Wonder is attempting to emancipate his people. His characters have a sense of composure and calm. They hold their space on the canvas confidently, as though they know that they belong. “In most cases I’m pushing their sovereignty,” he says. “I’m showing that we also have kings in our Black history. I want to highlight that we are all Kings and Queens and have our own African intelligence.”

The silver-green of the impepho leaves has become a common color in Wonder’s work, both in the garments and in backdrops. But the flower-patterned skin always seems to show through the fabric, which appears as thin as lace. “For a long time, people thought that darkness didn’t define beauty. I want to emphasize the blackness of the skin. It is so strong, bold and dark that it emerges through the fabrics,” he explains. “I want people to be given a space where they recognise their own potential.”

Wonder describes South Africa as a country experiencing growing pains. “This country still hasn’t grown up properly, and the inequalities are still so vast. The government doesn’t understand the culture of the youth. And if you haven’t figured out how to support the young people, what future can you possibly be aiming for?”

His great ambition is that he will be a part of a rising generation of global Black masters who bring their voices to the art world and begin to dominate the space. “I want to be part of a new heritage, a marker of an era,” he says. “I want any Black child in the world to walk into any gallery or museum and see themselves on the wall as a King or a Queen.”