Creative minds take many forms. But when we talk about creativity, we often focus on a very narrow range of people. In this series, Cedar Pasori talks to undeniably creative people whose experiences and expertise can teach us to look at the world differently. See the whole set here.

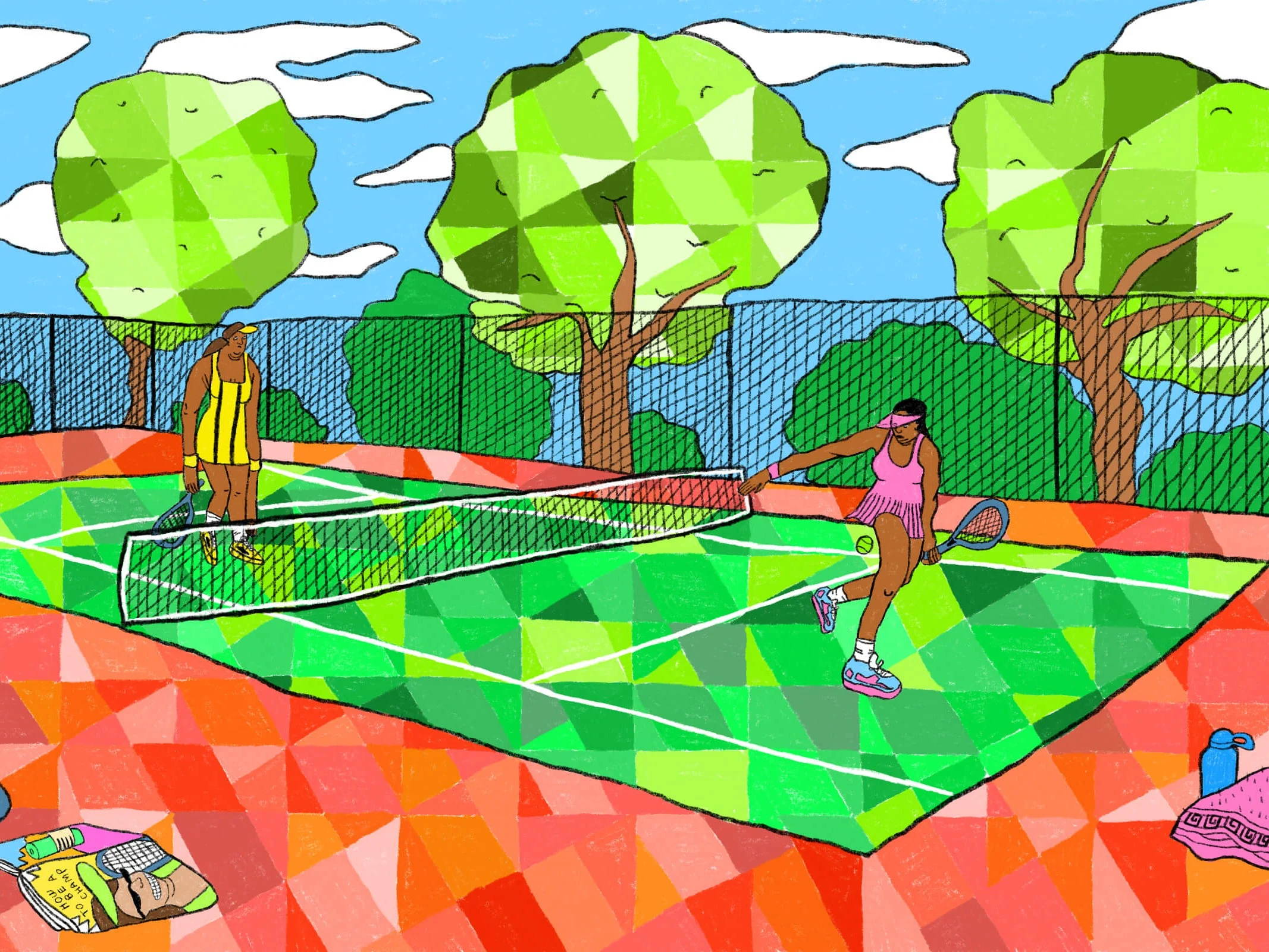

Illustrations by Miranda Jill Millen.

The night before the 2017 US Open, tennis coach Kamau Murray found himself reassuring a nervous Sloane Stephens. He placed clear, plastic wrap over the hotel room television and drew his well-researched strategies on top of the screen.

Sloane, who was 24 and ranked 83rd at the time, had miraculously made it to the finals. The next day, she won.

She was only the second tennis player Kamau had coached professionally. The first, Taylor Townsend – one of only two Americans to be world junior #1 – he’d coached on and off from the age of six until she went pro.

Kamau had become accustomed to a bespoke, pre-match routine with Sloane, for whom he downloads YouTube footage of opponents and texts bullet-pointed game plans. He developed these creative approaches through coaching hundreds of kids at his XS Tennis Village in his hometown of Chicago.

“Often, I’m just playing footage on a laptop and then covering it with something I can draw on,” he says. “I'll take a screenshot, put it into PowerPoint, and then use the drawing tools in the program to help the kids understand visually.”

Despite growing up tall in Michael-Jordan-era Chicago, this tactical attention to detail – and the rewards it brings – drew Kamau to tennis from a young age.

“Tennis distinguished me from every other kid I grew up around,” he says. Basketball was like a religion but his future lay on a tennis court, and he remembers his mother dropping him off at Chicago’s Jesse Owens Park when he was seven. He can quote the exact date in fact – “June 27, 1988” – and at the time, his main worry was making it home safely to Chicago’s South Shore while carrying a tennis racket.

I wanted to start an academy that would help kids and recreate the environment that made me the person I am today.

By 14 Kamau needed to practice with men as he was too strong to hit with other boys; by 16 he was getting tapped up for scholarships. But his plans to turn pro didn’t work out and after a stint in marketing in New York he came back to Chicago. He was saddened and surprised to see the once-bustling public tennis courts largely deserted.

Kamau sensed an opportunity. “I wanted to start an academy that would help kids and recreate the environment that made me the person I am today.”

He relocated to Chicago in 2006 and his parents refinanced their house so that he’d have a down payment for the Hyde Park space and he started hiring coaches and earning his own credentials. XS Tennis Village was officially born.

“XS is short for the word excess – greater than normal, better than average,” he explains. And Kamau’s commitment to excellence starts with a sophisticated view of the court.

“When people look at a tennis court, they see a lot of boxes. They see three big boxes and two rectangles on the other side of the court. I actually don't see the court that way. I see the tennis court like a kaleidoscope. I see angles of reflection, opportunities to redirect.”

Within this geometry of the tennis court, Kamau’s tactics are driven by constructing points through optimal positioning. “I see a lot of triangles on the other side of the court,” he adds. “Seeing the court this way helps to create ball patterns that win points.”

Kamau also believes the adage that the tennis court feels like “the loneliest place in the world” during a match. Despite his somewhat clinical strategies, offset by occasional yelling and unapologetic bluntness, he’s also a master of understanding and navigating the emotional taxation of the sport.

“A lot of the time, you have to take a step back and figure out what motivates the player,” he says. “You pick spots to coach. Often, the best coaching is not actually done on the court. Sometimes, it's over dinner, or breakfast, or on the car ride home. Creatively communicating information in the way that the athlete is willing to receive it is the biggest gift a coach can have – being able to say things in the language only they can hear and understand.”

A lot of the time, you have to take a step back and figure out what motivates the player.

After two years of building XS on a foundation of creative coaching philosophies, Kamau noticed that he and his team were developing some serious tennis talent. He decided to move XS into a better, more central facility in Washington Park towards the end of 2008. Four out of their first five students, which included Taylor Townsend, went on to receive full-ride university scholarships.

“Historically, you see facilities like this in wealthier communities,” he says. “I recall walking into facilities when I was a kid and feeling intimidated and out of place, like I needed a coaster under my water bottle.”

Kamau’s blueprint for making XS a new kind of sustainable tennis center is built on accessibility. He’s using a sliding-scale pricing structure, which provides scholarships and subsidies to families of every income. Some children pay nothing. He began connecting with local officials, donors, and influential supporters like former tennis champion, Billie Jean King (who helps babysit his kids sometimes too).

But building XS tested Kamau’s seemingly unbreakable persistence. In 2014, aged just 33, he suffered a stroke while driving Taylor to a tournament. He asked her to call 911 and instructed that she play her match that day.

"Once I was released from the hospital, I was coaching from a rolling office chair," Kamau says. "I had one of my other coaches doing all the throwing and hitting. I was on the side of the court in my chair yelling and screaming."

In November 2015, Kamau quit his day job to focus on XS and coaching Sloane. He welcomed her in the same holistic way that his college coach, Carl Goodman had – opening up his home in Chicago, where his protege does her own dishes.

"Tennis players usually spend more time with their tennis coach than anybody else," Kamau says. "With Sloane, my first job is to keep her safe. Second, I’m here to help her win. Third, I’m here to help her grow as a person. That's the job of any coach. I work for her."

I’m here to help her grow as a person. That’s the job of any coach. I work for her.

The night before the 2017 US Open was an unusual opportunity for Kamau to help Sloane on a human level. "To a kid, you coach every three shots, and to a pro, you coach every five," he says. “Every now and then, that pro will give you a moment to coach them as if they were a young person. To Sloane’s credit, because of her maturity, her honesty and opening up that window when she needed my help – that's why she won the US Open.”

Today, XS includes 27 courts spread across 13 acres in Chicago. Kamau – which means quiet warrior in Kenyan dialect – has built something unprecedented.

"My dad used to always say, you have two ears and one mouth for a reason," he says. "I'm definitely a person who values discretion and only talks when there's something important to say."