Recently, Chinese artist Tsang Kin-Wah has become interested in Confucianism, a philosophy, tradition and religion which stems from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE). Three words by scholar and statesman of the late Qing dynasty Zeng Guofan especially grabbed his attention – aspiration, knowledge and persistence.

“Somehow I agree with him that these three elements are the key to success,” he says. But it doesn’t end with this one theory. Tsang’s reading habits show his interest in a wide variety of philosophical and religious ideas. They are the inspiration for his own writings, which in turn become new artworks in the form of text-based video installations.

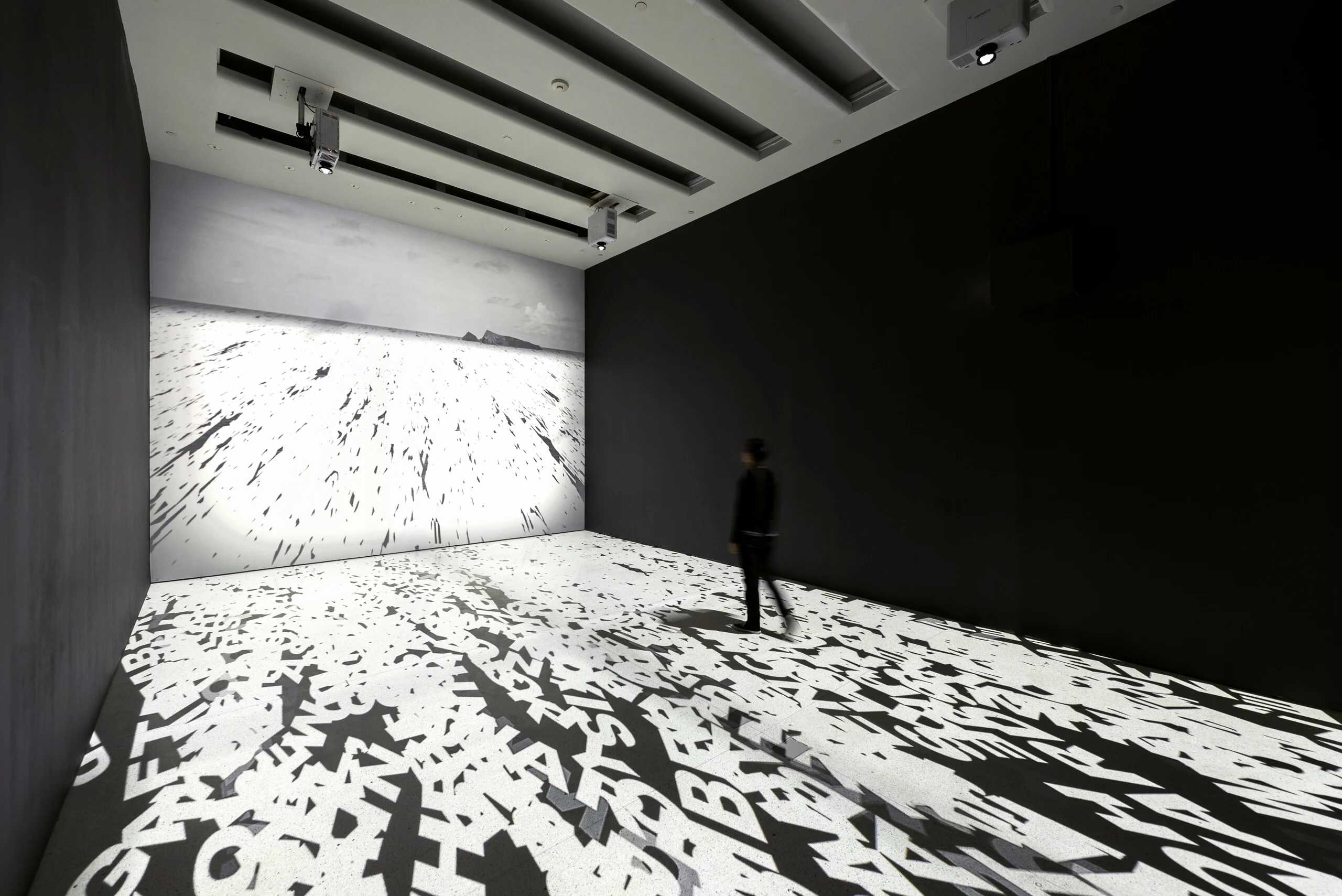

Words are ever present in Tsang’s intriguing video installations. Like a lone voice in the dark, they begin with the appearance of one word or poetic phrase. New sentences appear or the same phrase repeats itself, eventually filling the entire space. It’s as if many voices try to talk above one another in a crowded room, until the ceiling, walls or floor become an abstract color plane before fading into darkness to start again.

The pace at which new text appears increases as the sound or music intensifies to build tension. “The thief, the enemy, the wrath, the purge, the omen, the disasters, the righteous, the wicked, the darken sun, the bloody moon, the mighty wind, the falling stars.” The words start out readable so that the audience can grasp the content of the piece, but eventually become illegible when the feeling of the artwork becomes more important. The interpretation of the phrases is left up to the viewer to make sense of, or not.

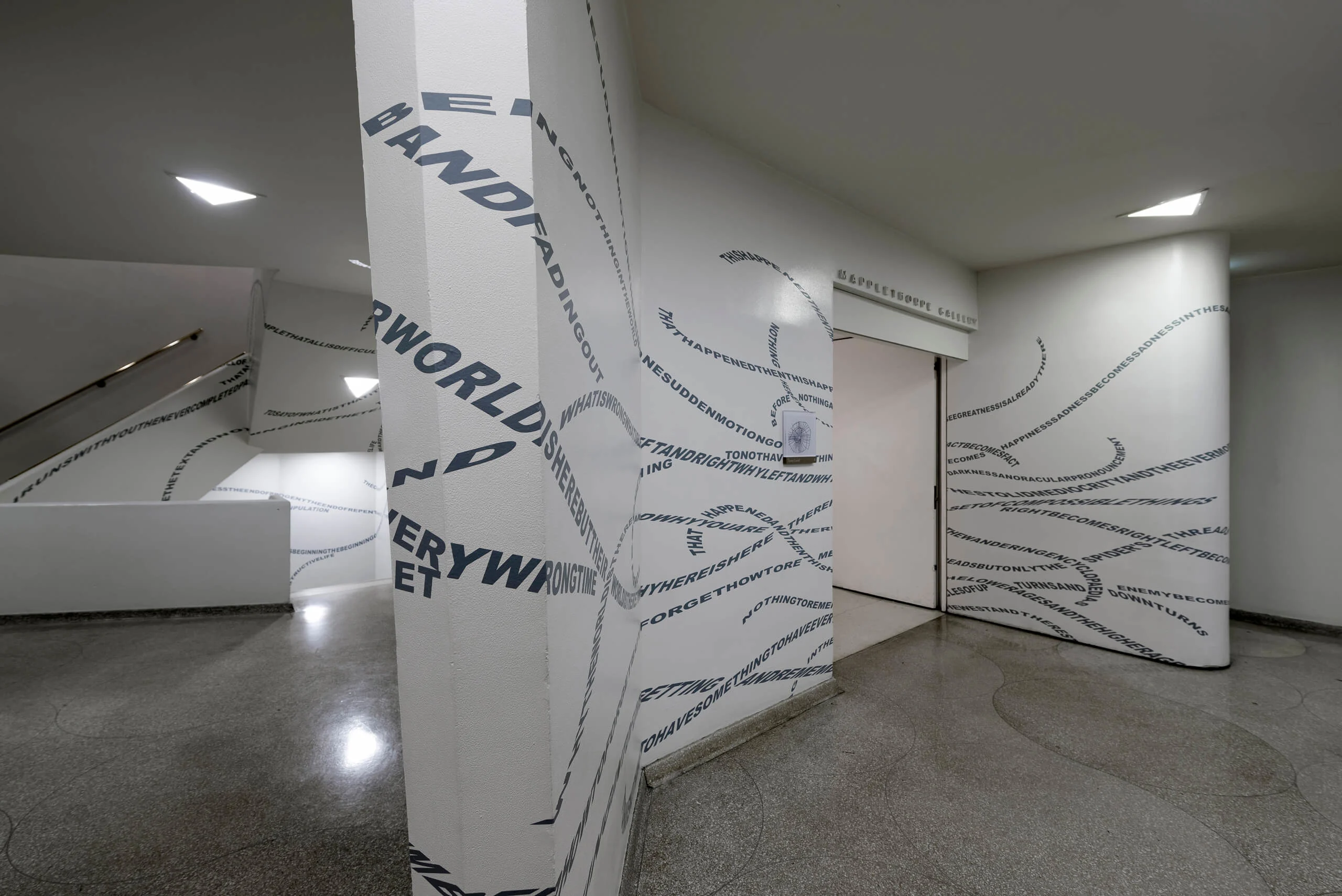

Tsang gained attention early on in his career for his wallpaper art, beautiful intricate floral patterns. But, upon closer inspection you see they are made from cleverly designed curse words and profane phrases hidden in plain sight.

For these pieces he used English words because, being his second language, it allows him some distance from the topics he explores. “There was a time that my English text was translated to Chinese and all of a sudden I felt a gruesome realization that I would not be able to write the same thing in Chinese,” he says.

Arial Black is his font of choice. “Since most of my works are related to strong emotions or heavy topics, I like to have a font which can show its boldness but, at the same time, isn’t too tall/slim or too short/flat. Arial Black is rather simple, clean and neat, and even a little dull and stubborn.”

How the text animates depends both on the space and on how Tsang intends a viewer to experience it, snaking or swimming across the wall. Even when his installations are still, the words seem alive, stretching and curving organically around corners and up staircases like roots seeking water.

Contrasting concepts co-exist in Tsang’s work, one piece could make reference to both the Bible (he went to a christian school growing up in Hong Kong) and Nietzsche. “I do not believe in a single religion or ideology anymore,” he says.

Like his work stems from multiple references, he lives his life by ideas from many sources. “I just take and believe some small parts of each theory or philosophy,” he explains.“Karma from Buddhism, some ideas of Confucius, but at the same time I like Heraclitus’ flux doctrine, a bit of Stoicism and a bit of materialism and more.”

The music Tsang uses in his installations not only helps to set the tone of the work but also carries references to the history of music or scores in films. Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra was used in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film Tsang describes as highly-influenced by Nietzsche. He uses altered samples of both the music and the visuals in The Sixth Seal and The Infinite Nothing, in which he imitated the opening scene of the film.

Tsang’s artistic exploration is also a pursuit to better understand human nature. “I am interested in observing people, including myself, to see how they behave and react. Sometimes you can tell what people think just by a very tiny gesture or sign. I find this is very fascinating.”

He is especially interested in our dark side. “I also think most problems and issues in society and the world can actually be traced back to its fundamental point, which is the human being and our rather not so good nature,” he says.

“I don’t have any specific sayings that I live by, but I do often remind myself to be a good person and a better man.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.