In the very far east of Russia, right above Japan, there’s a small island called Sakhalin (no this is not the beginning of a fairytale). It’s where young illustrator Toma Vagner grew up dreaming of a life as an artist.

But, coming from such a small island, there wasn’t really an artistic scene where she could develop her skills and start a career. “It was more DIY – it's not like people are making a living from what they create. It's just something they regard as a hobby,” Toma explains.

“When I was maybe 17 I found out there is a school in New York called the School of Visual Arts. It quickly became my dream,” she says.

Although she started off studying graphic design – because her parents thought it would give her more job security – she secretly switched to illustration in her freshman year. “I never regretted this choice really.” Fast forward to 2018, she’s a recent graduate, taking on commissions from none other than Harry Styles.

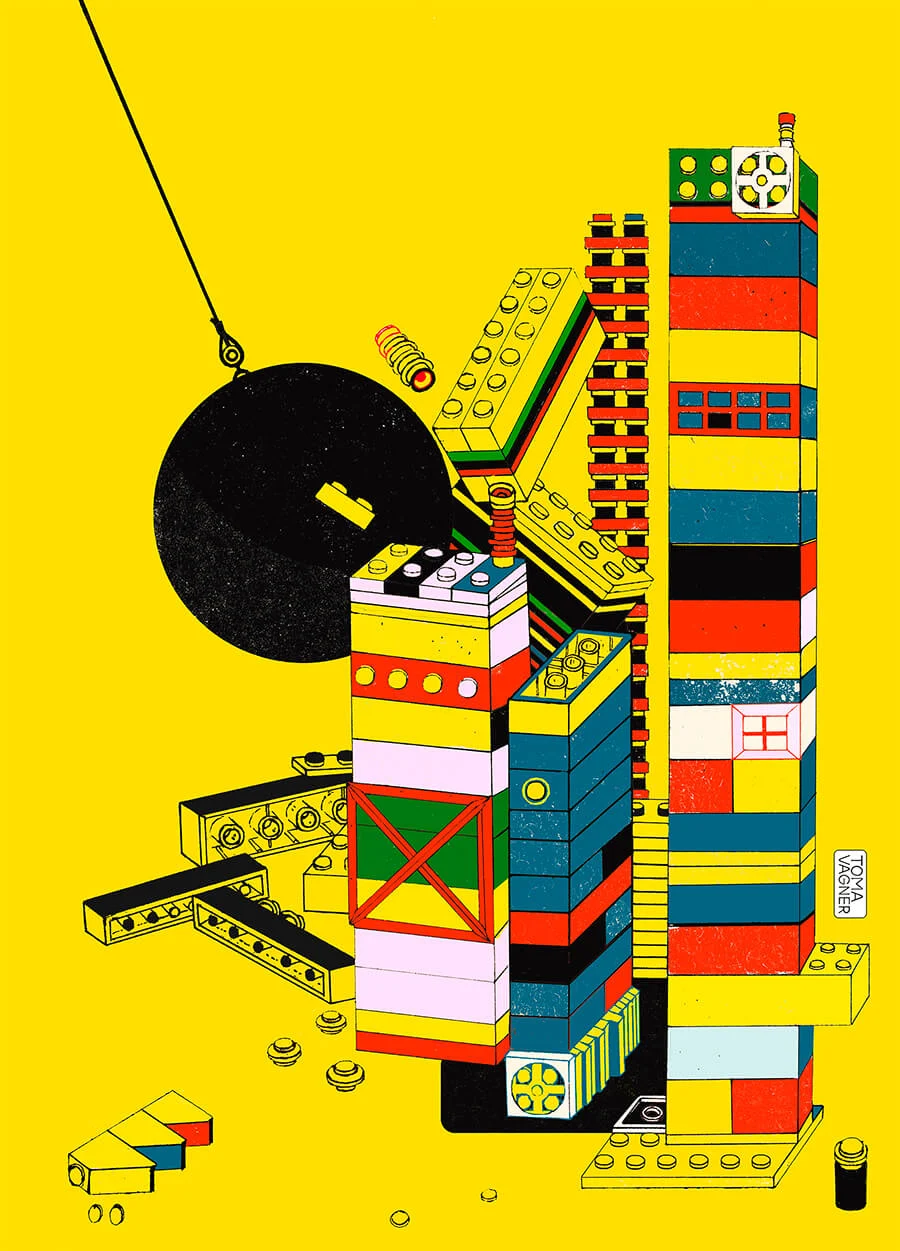

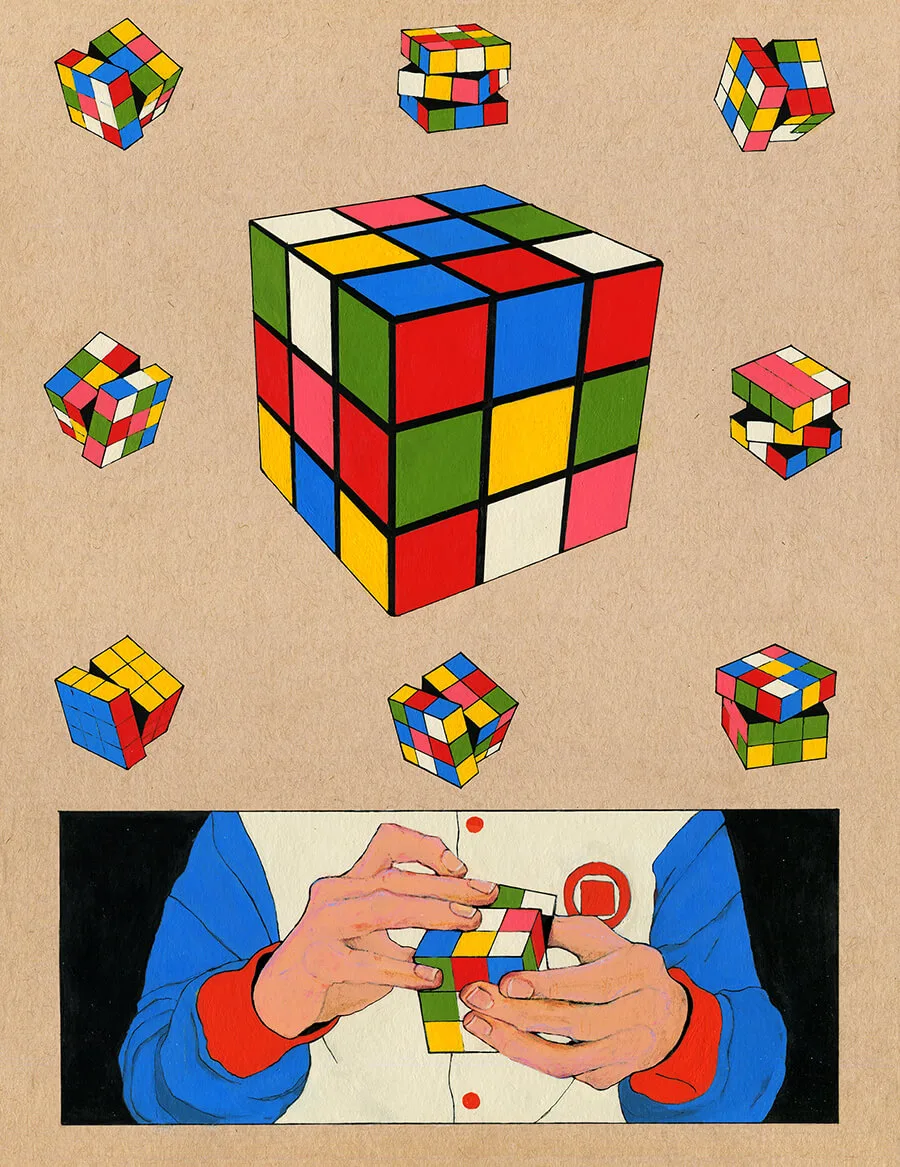

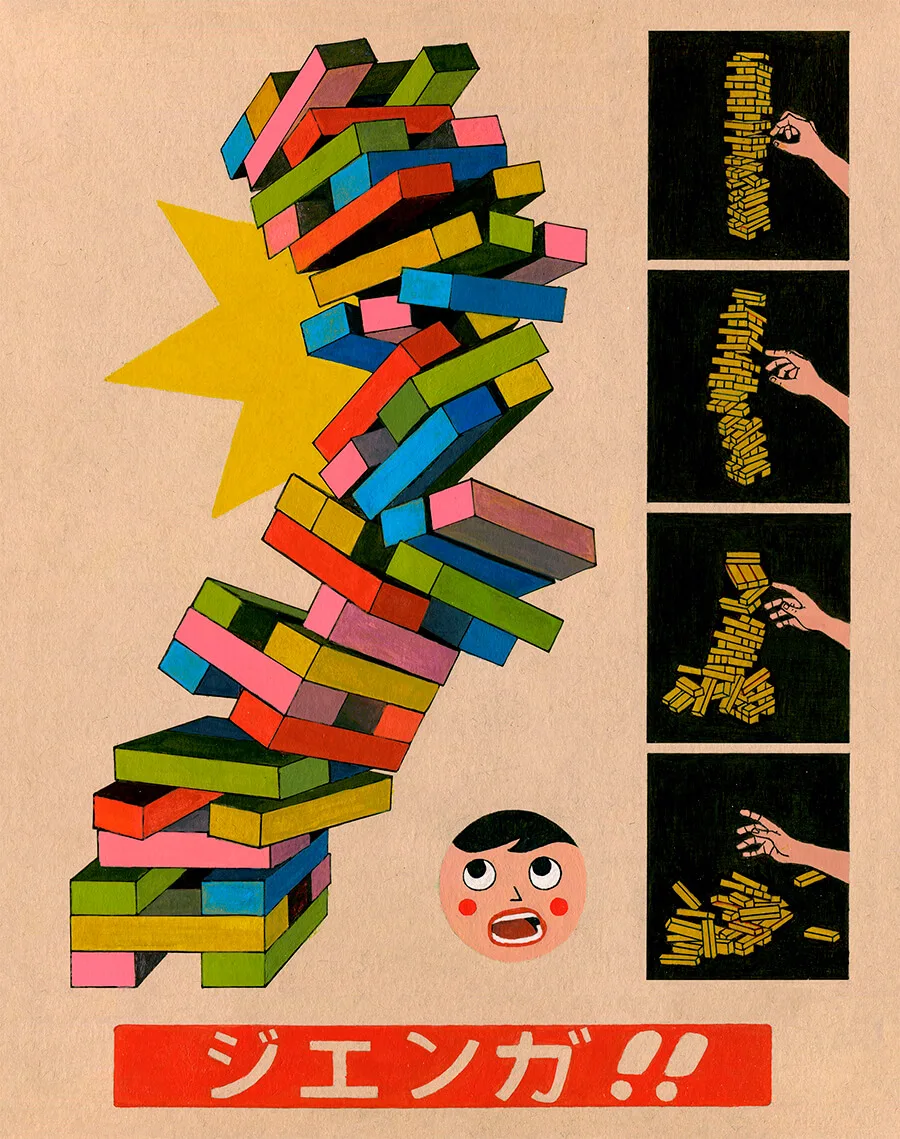

Even though she has moved across oceans to fulfill her dreams, in her art Toma hasn’t shaken off the influences from her childhood. From rubik’s cubes to Jenga to paper cut-out dolls, she illustrates the games she used to play (or still likes to play).

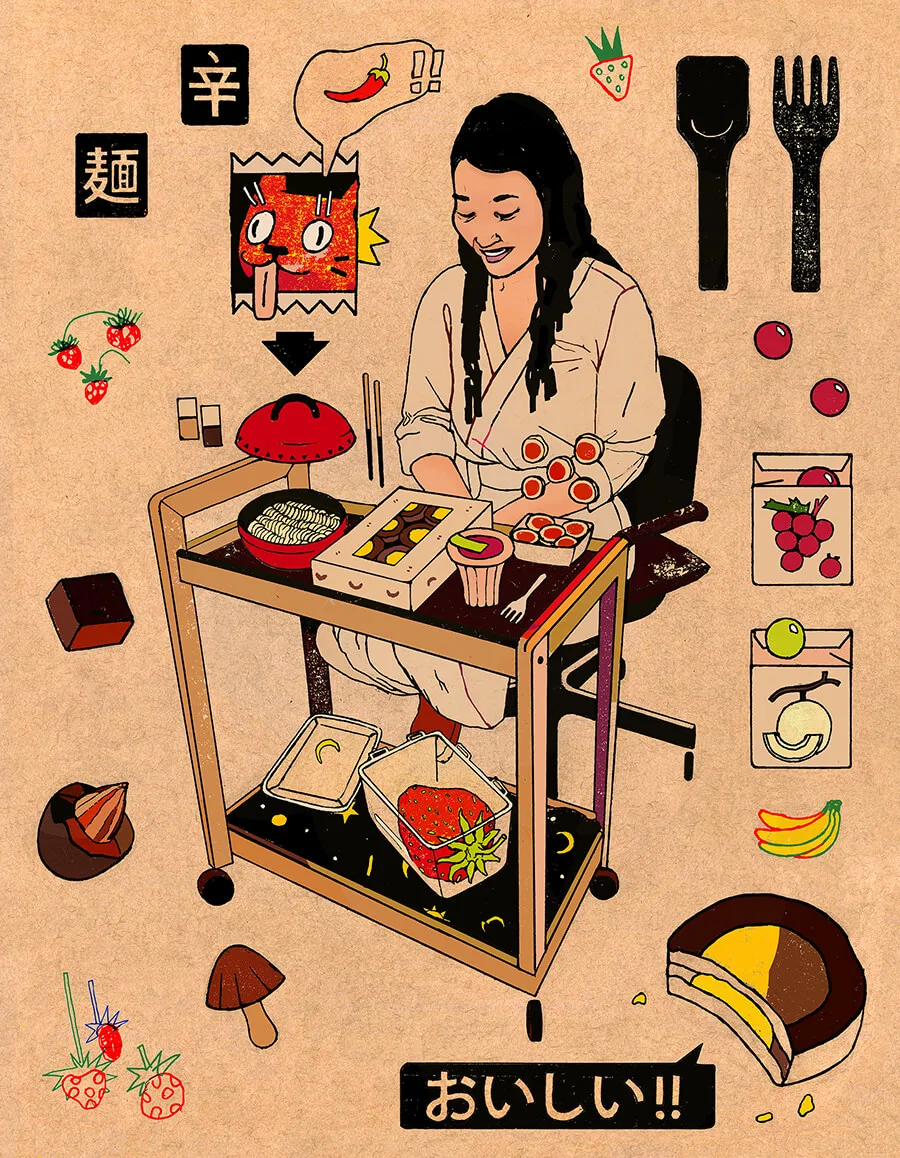

It’s not just the games that influenced her illustrations. When she was growing up her father was a sailor who traveled to Japan a lot. “Sakhalin was very influenced by the Japanese in the 1950s because the south was occupied by Japan. So we still have some remains, like architecture and parts of Japanese culture and a lot of Asian-Russians there,” Toma explains.

“In the 90s we didn't have any Japanese products anymore. But my father would go on business trips to Japan and Korea and he’d bring home a big suitcase of goods. I had lots of items from Japan that my friends didn't have.”

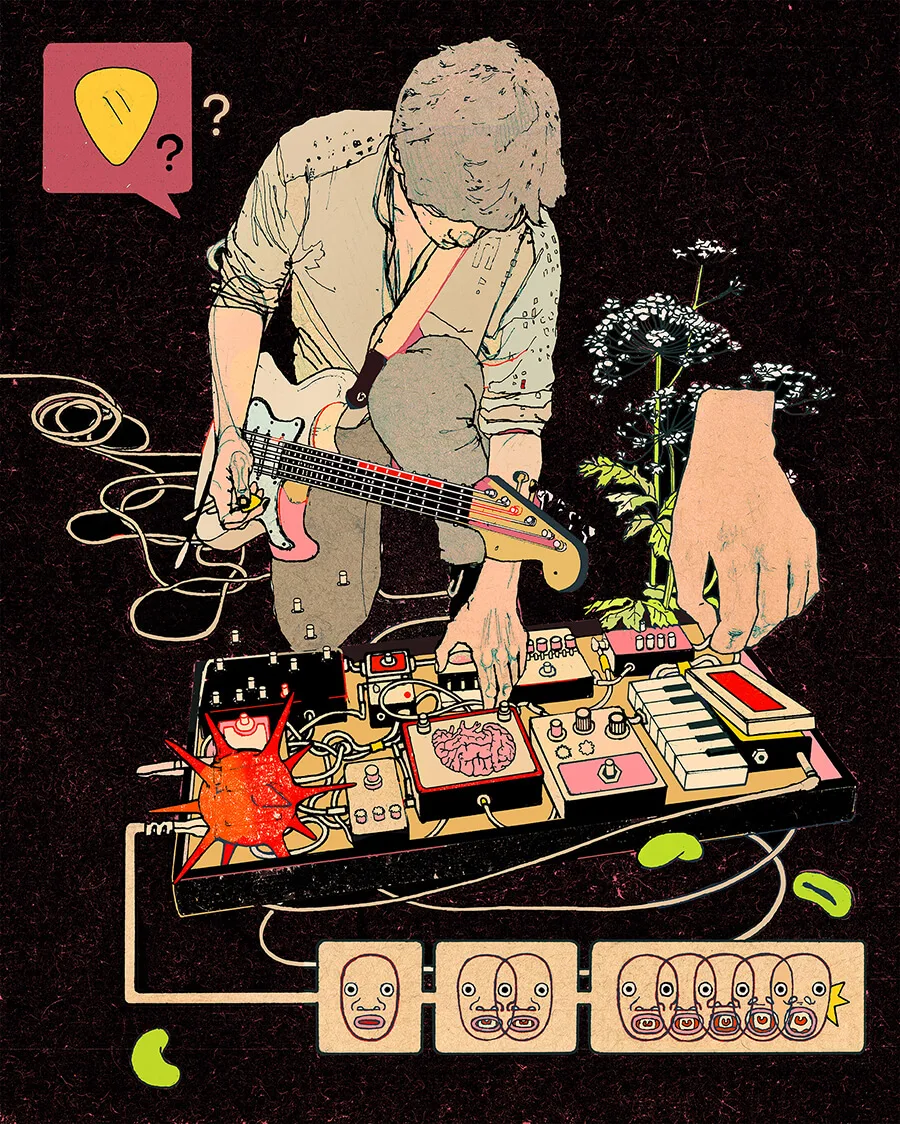

Together with one of her friends, whose dad was also a sailor, she developed a love for Japanese comics. “It was all in Japanese so we didn't understand anything, it was just pictures and cartoons,” she says. “Japanese bubble gum was a big part of it, because they had small cartoons printed on the wrappers and it was really fun. It was all in Japanese, but they were still funny, the way they were drawn.”

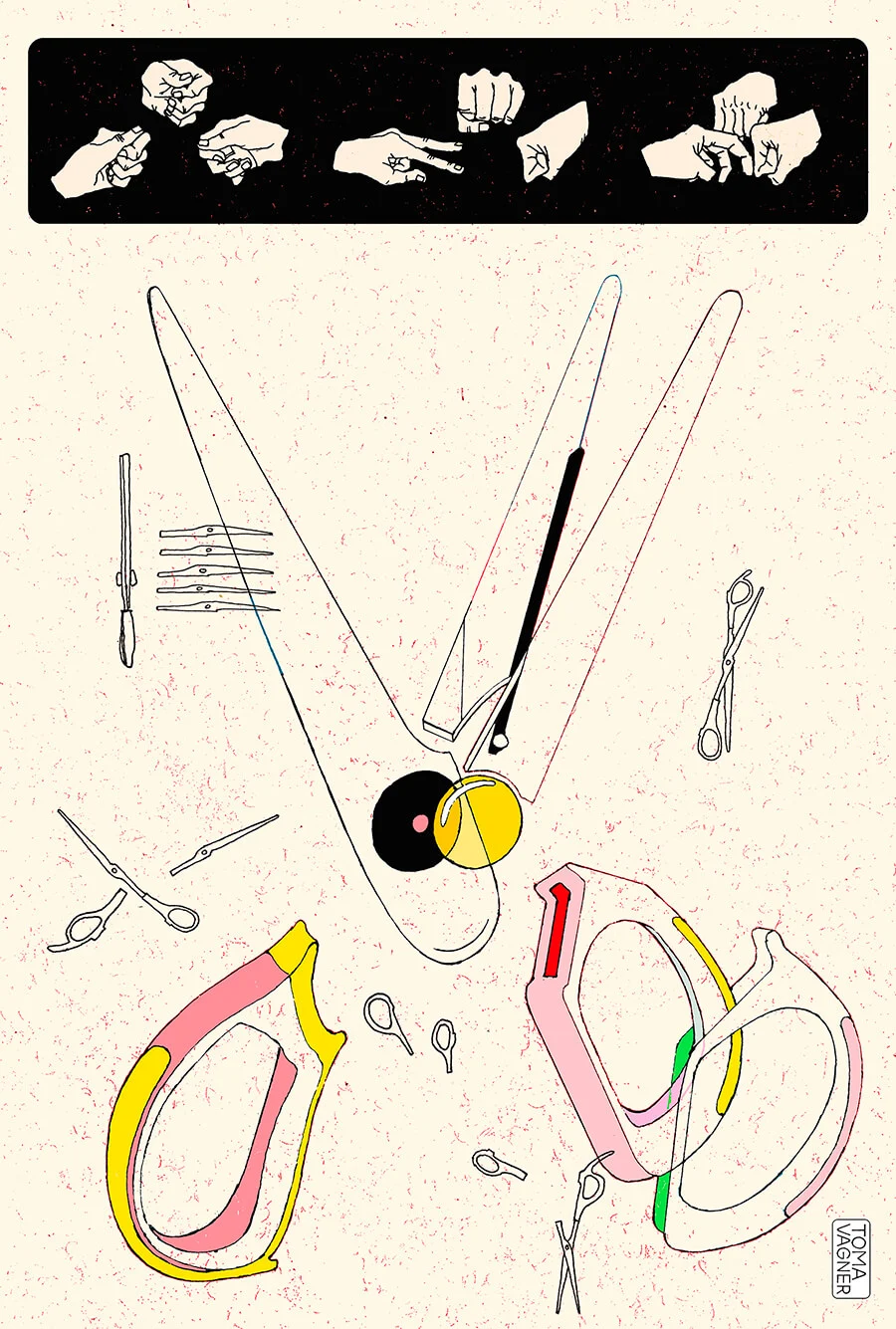

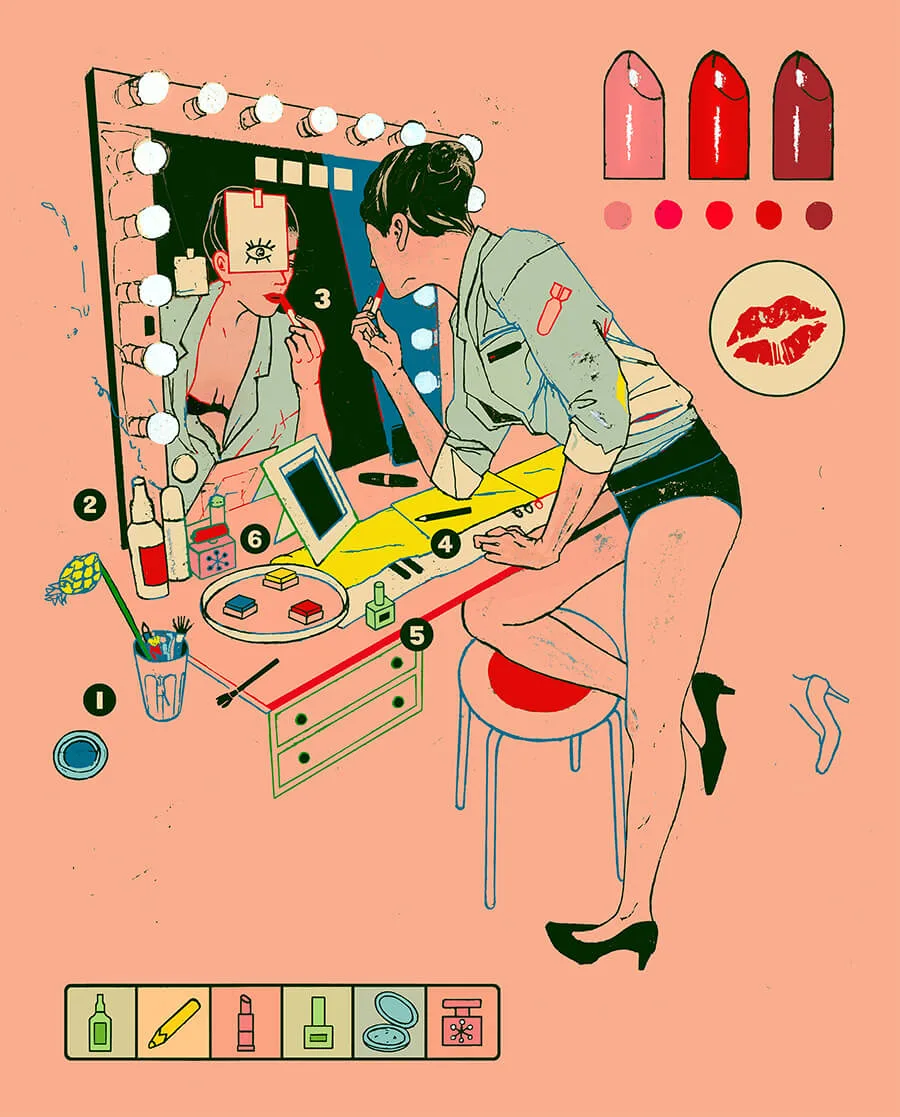

These bubble gum wrappers have made their way into her work in the form of small panels we are used to seeing in comics. She draws the main subject, like the rubik’s cube, and picks different elements from it which she then puts in small boxes as an explanation of the theme. Like a one-page manual, we see the toy, and on the sides Toma adds small instructions on how to assemble one. “I actually learned all the algorithms, because I feel responsible for knowing how to solve it.’”

Words by Suzanne Tromp